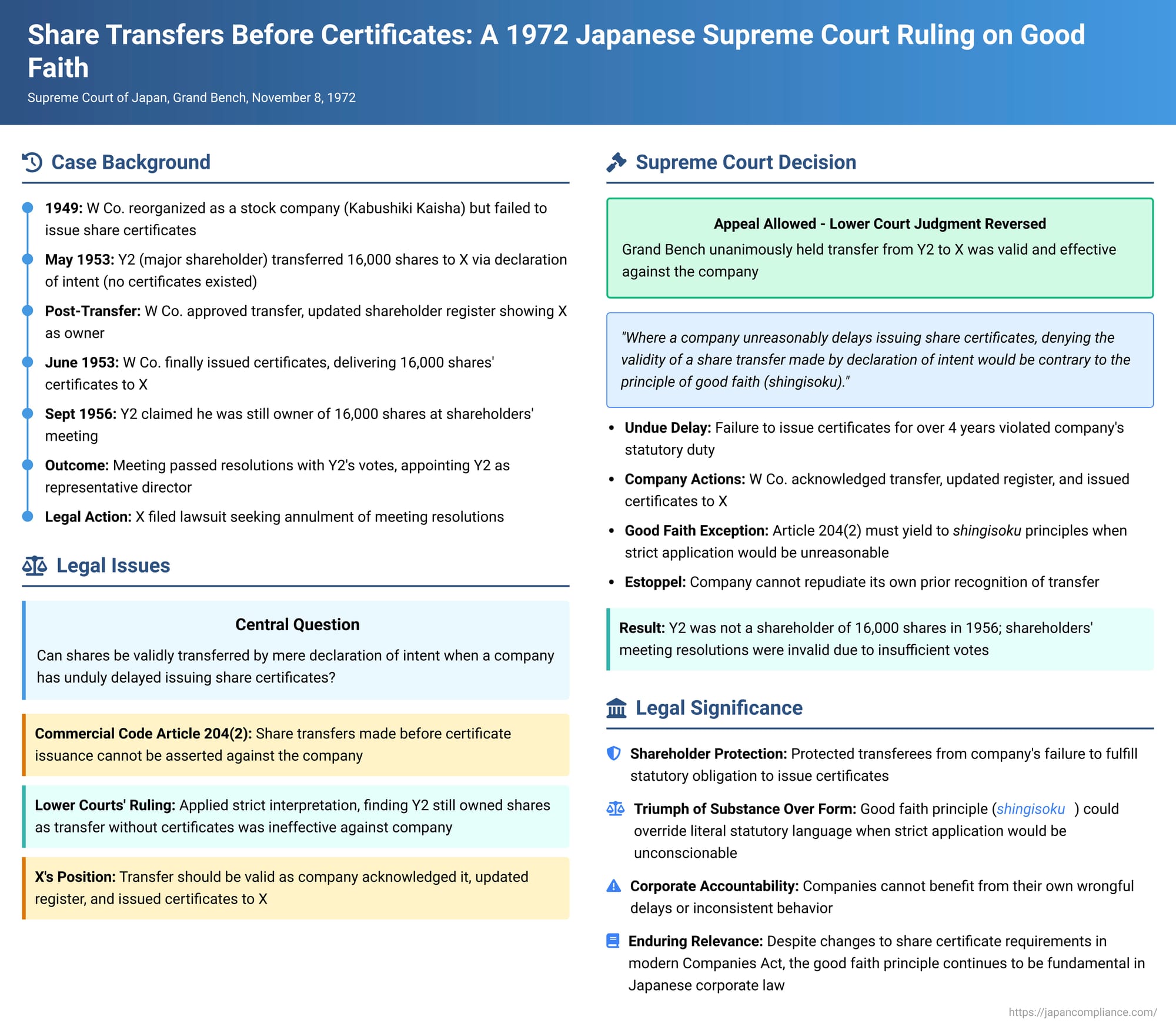

Share Transfers Before Certificates: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Good Faith and Undue Delay

Date of Judgment: November 8, 1972

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction

In traditional corporate law, share certificates have long served as tangible proof of stock ownership and a key instrument for effecting transfers. Japanese corporate law historically placed significant emphasis on these certificates. However, this system could lead to complications if a company failed to fulfill its obligation to issue these certificates in a timely manner. This raises a critical question: can shares be effectively transferred if the company itself has not yet issued the formal share certificates, especially if the company has unduly delayed doing so?

This complex issue was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on November 8, 1972. The case explored the validity of a share transfer made by a mere declaration of intent, without the physical delivery of certificates, in a situation where the company had not issued certificates for several years. The ruling delved deep into the interplay between statutory requirements, the principle of free transferability of shares, and the overarching legal doctrine of shingisoku – the principle of good faith.

The Prevailing Legal Landscape: Share Transfers Under the Commercial Code

At the time of the events in question and the judgment, the Japanese Commercial Code contained specific provisions governing share transfers and the issuance of share certificates:

- Freedom of Share Transfer: The Code generally upheld the principle that shares in a stock company (Kabushiki Kaisha) were freely transferable. Pre-1966 amendments even stipulated this freedom could not be restricted by a company's articles of incorporation.

- Role of Share Certificates in Transfer: For registered shares, the transfer was typically to be effected by the delivery of the share certificate, often accompanied by an endorsement or a separate transfer deed.

- Company's Duty to Issue Certificates: The Code mandated that a stock company must issue share certificates without delay after its incorporation or after the payment date for new shares. This was seen as essential to facilitate the very transferability the Code championed.

- Transfers Before Certificate Issuance: Critically, a provision (Article 204, Paragraph 2 of the then Commercial Code) stated that a transfer of shares made before the issuance of share certificates could not be asserted against the company (i.e., it was ineffective vis-à-vis the company).

This last rule, on its face, seemed to create a clear bar to recognizing transfers made in the absence of issued certificates. The W Co. case would test the limits of this rule, particularly when a company's own inaction contributed to the predicament.

The Facts of the W Co. Case

The dispute involved a company named W Co. and two of its shareholders, X and Y2.

- W Co.'s Background and Failure to Issue Certificates: W Co. was originally established as a limited company (Yugen Kaisha) in 1940. It was reorganized into a stock company (Kabushiki Kaisha) in 1949. Despite this reorganization and its operation as a stock company, W Co. had, for over four years, failed to issue any share certificates to its shareholders.

- The Share Transfer: X was a shareholder in W Co., holding 100 shares. Y2 was a major shareholder, holding 16,000 shares. In early May 1953, Y2 transferred his entire holding of 16,000 shares to X. This transfer was effected simply by a declaration of intent between Y2 and X, as no share certificates existed to be delivered.

- Company Acknowledgment and Subsequent Certificate Issuance: Significantly, W Co. was made aware of this transfer. The company formally approved the transfer and updated its shareholder register (kabunushi daicho) to reflect X as the owner of these 16,000 shares. Furthermore, on June 25, 1953, W Co. finally issued share certificates, and importantly, it delivered certificates representing these 16,000 shares to X, with X listed as the original shareholder for these newly issued certificates.

- The Contested Shareholders' Meeting: Several years later, in 1956, events took a contentious turn. Y2, the original transferor of the 16,000 shares, along with another individual (W.I.), sought and obtained court permission to convene a shareholders' meeting of W Co. This meeting was held on September 16, 1956.

- Disputed Voting Rights and Resolutions: At this shareholders' meeting, Y2 asserted that he was still the rightful owner and voter of the 16,000 shares he had previously "transferred" to X. The voting rights were calculated on this basis: X with 100 shares, Y2 with 16,000 shares, W.I. with 150 shares, and another shareholder Y.K. with 1,550 shares (totaling 17,800 shares considered for voting). X disputed Y2's claim and eventually left the meeting. The remaining attendees, relying on Y2's purported 16,000 votes, passed resolutions to dismiss the company's existing officers and appoint a new slate of officers. Subsequently, a board of directors meeting, composed of these newly appointed directors, elected Y2 as the representative director of W Co.

- X's Legal Challenge: X filed a lawsuit seeking, among other things, the annulment of the resolutions passed at the September 1956 shareholders' meeting. X argued that Y2 was no longer a shareholder of the 16,000 shares and thus the resolutions were passed without the requisite quorum and voting power.

The Lower Court's Strict Interpretation

The lower courts, leading up to the Supreme Court appeal, sided with W Co. and Y2. They applied a strict and literal interpretation of Article 204, Paragraph 2 of the Commercial Code. Their reasoning was straightforward: the transfer of the 16,000 shares from Y2 to X occurred before W Co. had issued share certificates for them. Therefore, regardless of the intent of Y2 and X, and even regardless of the company's initial acknowledgment, the transfer was legally ineffective against W Co.

Consequently, the lower courts concluded that Y2 remained the legal shareholder of the 16,000 shares. The resolutions passed at the shareholders' meeting were, in their view, validly enacted with Y2's voting power. X's claims were dismissed.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Landmark Ruling (November 8, 1972)

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench, in its unanimous decision, took a significantly different approach, ultimately reversing the lower court's judgment on the key issues.

Rejecting a Rigid Application of the Law

The Court began by acknowledging the Commercial Code provisions, including the rule that pre-issuance transfers are ineffective against the company. However, it signaled a departure from an unyieldingly rigid application of this rule, especially when such application would lead to an unjust outcome.

Legislative Intent, Shareholder Protection, and the Principle of Good Faith (Shingisoku)

The Supreme Court emphasized that the legal framework governing shares aimed to ensure their free transferability. The requirement for companies to issue share certificates promptly was integral to this objective. The Court reasoned:

- Premise of Prompt Issuance: The rule rendering pre-issuance transfers ineffective against the company (Article 204, Paragraph 2) implicitly presupposes that the company will diligently fulfill its duty to issue share certificates. The rule is designed to ensure smooth and accurate dealings related to shares, with the company maintaining control over recognition until certificates are formally issued.

- Undue Delay Frustrates Legislative Intent: If a company unduly delays the issuance of share certificates, it effectively obstructs the free transfer of shares. This not only contravenes the spirit of the Commercial Code but also raises serious concerns under the fundamental legal principle of shingisoku (often translated as "good faith and trust" or the "principle of good faith"). Shingisoku dictates that rights must be exercised and duties performed honestly, fairly, and reasonably.

- The Core Finding – An Exception Based on Good Faith: The Court declared that while the rule in Article 204, Paragraph 2 should not be lightly disregarded (as this could create legal uncertainty), an exception must be recognized. Specifically, where a company, contrary to the intent of the Code, unreasonably delays the issuance of share certificates to such an extent that denying the validity of a share transfer (made without certificates) against the company would be contrary to the principle of good faith, then such a transfer, even if made by a mere declaration of intent, can be deemed valid and effective against the company. In such circumstances, the company is estopped from denying the transfer's validity based on the absence of prior certificate issuance and is obligated to treat the transferee as a legitimate shareholder.

- The Supreme Court explicitly stated that this ruling modified a previous, more rigid view it had expressed in a 1958 case.

Application to the Facts of the W Co. Case

Applying this reasoning to the specific facts before it, the Supreme Court found compelling grounds to rule in favor of X:

- Undue Delay by W Co.: W Co.'s failure to issue any share certificates for over four years after its transformation into a stock company was deemed a clear and undue delay, contrary to the Commercial Code's requirements.

- Transfer by Declaration of Intent: Y2 transferred his shares to X by a declaration of intent during this period of undue delay.

- Company's Own Actions – The Decisive Factor for Good Faith: Crucially, W Co. did not simply remain passive. It actively acknowledged and approved the transfer from Y2 to X. It recorded X as the shareholder of the 16,000 shares in its official shareholder register. And, subsequently, it issued share certificates for these very shares directly to X, naming X as the shareholder.

For W Co. to later allow Y2 to assert ownership over these same shares at the 1956 meeting, effectively repudiating its own prior actions and records, was a profound breach of the principle of good faith. The Court found it "unreasonable" and "contrary to faith and trust" to deny the transfer's validity against the company under these circumstances.

Consequences of the Ruling

Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded:

- The transfer of the 16,000 shares from Y2 to X was effective against W Co.

- Therefore, Y2 was not a shareholder of those 16,000 shares at the time of the September 1956 shareholders' meeting.

- The resolutions passed at that meeting, which relied on Y2's purported voting power from these 16,000 shares, were passed with insufficient valid votes (only 1,700 shares, comprising X's original 100 plus those of W.I. and Y.K., assuming their shares were validly counted, were eligible). This fell far short of the quorum and voting thresholds required by the Commercial Code and W Co.'s articles of incorporation.

- Consequently, the shareholders' meeting resolutions were annulled.

- The subsequent board of directors' resolution appointing Y2 as representative director, being predicated on the invalid shareholders' meeting, was also declared null and void.

- The Court also confirmed that Y2 was not a shareholder of W Co. (in respect of the 16,000 shares).

Significance of the Decision and Doctrinal Underpinnings

The 1972 Grand Bench decision was a significant development in Japanese corporate law.

- Protection of Shareholders: It provided a crucial measure of protection for shareholders who might otherwise be prejudiced by a company's failure to comply with its statutory obligation to issue share certificates. It prevented companies from using their own default to undermine legitimate share transactions.

- Centrality of Shingisoku: The ruling underscored the power and importance of the shingisoku principle as a tool for achieving equitable outcomes, even when faced with seemingly clear statutory language. It demonstrated that formal rules could be tempered by fundamental principles of fairness and good faith, especially when one party's conduct was inconsistent or unconscionable.

- Doctrinal Basis: While the PDF commentary accompanying this case notes a scholarly debate on whether the ruling was based more on a "reasonable time having passed" for certificate issuance or purely on the good faith principle, the judgment text itself heavily emphasizes shingisoku. The undue delay was a factual predicate that triggered the good faith concerns, particularly when combined with the company's subsequent inconsistent behavior (initially recognizing the transfer, then effectively allowing its repudiation).

The specific facts of the W Co. case, particularly the company's explicit acknowledgment of the transfer and subsequent issuance of certificates to X, made the argument for applying the good faith principle exceptionally strong.

Relevance in Modern Japanese Corporate Law

The legal landscape surrounding share certificates in Japan has evolved since 1972, primarily with the enactment of the Companies Act.

- Changes in Mandatory Certificate Issuance: Under the current Companies Act, the obligation for a company to issue physical share certificates is no longer universal. It is now largely limited to:

- "Public companies" (as defined in the Companies Act, generally those whose articles do not restrict transfer of all shares) that specifically opt in to issue share certificates in their articles of incorporation.

- "Non-public companies" that opt in to issue certificates in their articles and are then specifically requested by a shareholder to issue a certificate for their shares.

For many companies, particularly those whose shares are managed through a book-entry transfer system, physical share certificates are not routinely issued.

- Diminished Factual Relevance: Consequently, the precise factual scenario of the W Co. case – a company being broadly obligated to issue certificates and failing to do so for an extended period – is less common today for companies that have not opted to issue certificates.

- Enduring Importance of Shingisoku: Despite these changes, the Supreme Court's 1972 ruling remains highly significant. The core principle it champions – that corporate actions and shareholder dealings must adhere to shingisoku (good faith) – is a timeless and fundamental tenet of Japanese contract and corporate law. This principle continues to be invoked in a wide array of corporate disputes to prevent abuse of rights and to ensure fair dealing. While the specific rules on share certificates have changed, the judgment's powerful articulation of good faith in the context of share ownership and transfer continues to resonate and inform judicial reasoning.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench decision of November 8, 1972, stands as a landmark in Japanese corporate jurisprudence. It adeptly balanced the formal requirements of the Commercial Code regarding share certificates with the overarching equitable considerations embodied in the principle of good faith. By carving out an exception to the rule on pre-issuance transfers in cases of undue delay and conduct contrary to shingisoku, the Court protected the legitimate expectations of a transferee and held a company accountable for its own inconsistencies and failures.

While the statutory framework for share certificates has since been modified, the decision's robust application of the good faith principle has an enduring legacy, reminding corporations and shareholders alike that legal rights and obligations must be approached with fairness, honesty, and a respect for reasonable expectations.