Share Transfer Restrictions in Closely-Held Japanese Corporations: Analyzing Recent Case Law

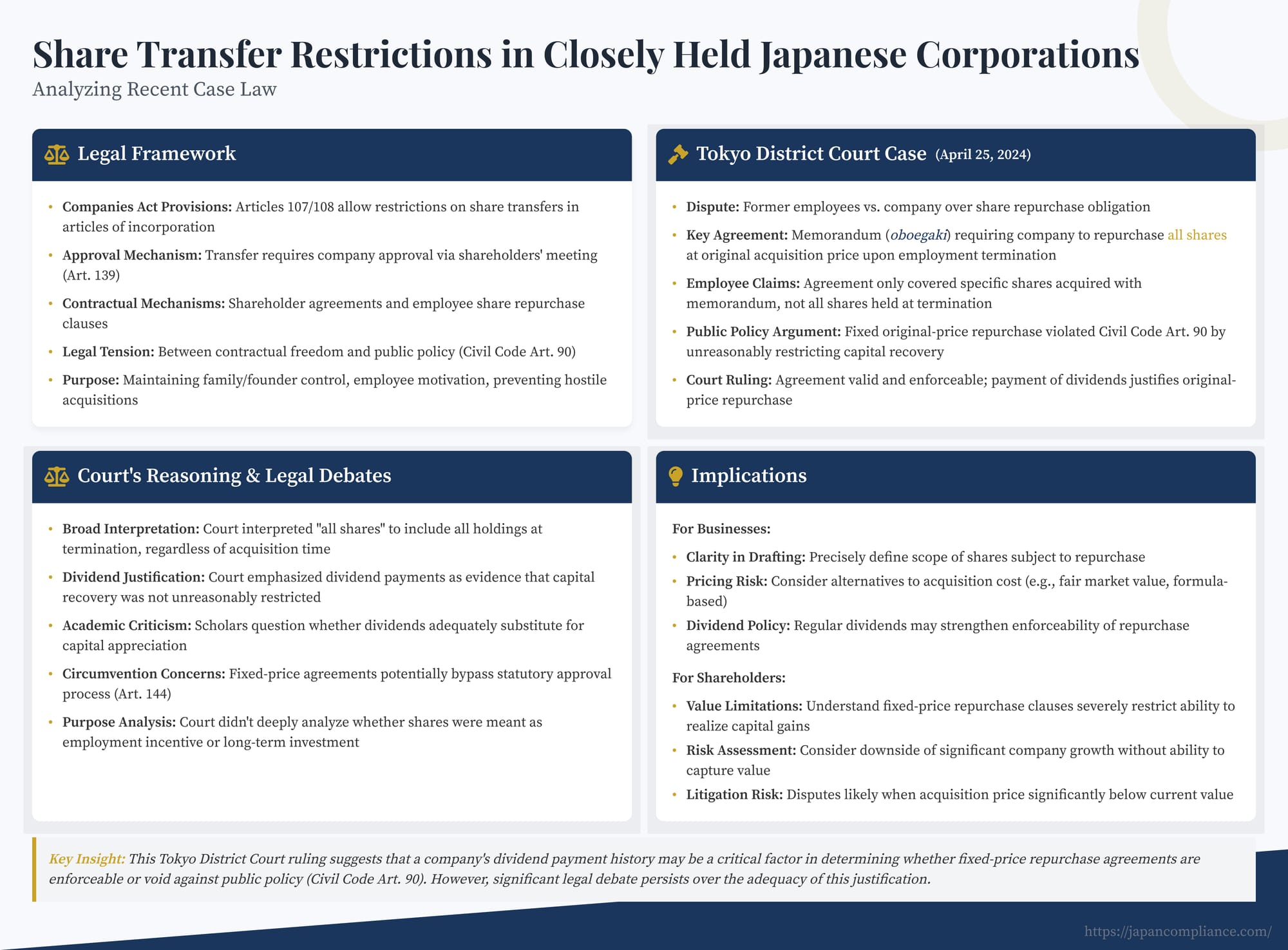

TL;DR: A 2024 Tokyo District Court ruling upheld an employee share-repurchase clause that forced resale at acquisition cost—so long as dividends had been paid—underlining the fine line between legitimate control of ownership and public-policy violations in Japan’s closely-held corporations.

Table of Contents

- Share Transfer Restrictions in Japanese Non-Public Companies

- The Case Study: Tokyo District Court, April 25 2024

- Analyzing the Court's Reasoning and Legal Debates

- Implications for Businesses and Shareholders

- Conclusion

Introduction

Maintaining control over ownership is a paramount concern for many closely-held corporations worldwide. In Japan, non-public stock companies (kabushiki kaisha that are not kokai kaisha, meaning they restrict the transfer of all shares) frequently utilize share transfer restrictions embedded in their articles of incorporation to manage shareholder composition and prevent unwanted third parties from gaining stakes. Beyond these formal restrictions requiring company approval for transfers, companies often employ contractual agreements, such as shareholder agreements or specific clauses in employment contracts or memoranda, to further regulate share ownership, particularly among employees.

These contractual mechanisms, especially those mandating share repurchase upon certain events like employee termination, can create significant legal complexities. A key question often arises: are such agreements, particularly those setting a fixed repurchase price (like the original acquisition cost), enforceable under Japanese law, or do they unreasonably restrict a shareholder's ability to realize the value of their investment, potentially rendering them void against public policy?

A recent Tokyo District Court decision, rendered on April 25, 2024 (Case No. Reiwa 4 (Wa) 8590), provides valuable insights into how Japanese courts may approach these issues. This article analyzes the legal framework governing share transfer restrictions in Japan's non-public companies, delves into the facts and ruling of the April 2024 case, examines the court's reasoning, discusses the surrounding legal debates, and explores the implications for businesses structuring employee share schemes and for shareholders subject to such agreements.

1. Share Transfer Restrictions in Japanese Non-Public Companies

Japanese corporate law offers specific tools for non-public companies (hi-kokai kaisha) to control their ownership structure.

- Restrictions in Articles of Incorporation: The Companies Act allows these companies to stipulate in their articles of incorporation (teikan) that any transfer of shares requires the company's approval (Companies Act, Art. 107, 108). For companies without a board of directors (torishimariyakukai setchi kaisha de nai kaisha), this approval typically requires a resolution at a shareholders' meeting (Art. 139). This mechanism serves common purposes like ensuring ownership remains within a family, among founding members, or within a select group of employees, and preventing hostile acquisitions.

- Contractual Agreements: Beyond the articles, companies may enter into separate contracts with shareholders that impose additional restrictions or obligations. Common examples include:

- Shareholder Agreements: Agreements among shareholders regulating transfers, voting, etc.

- Employee Share Repurchase Agreements: Clauses within employment contracts or separate memoranda requiring employees to sell their shares back to the company (or a designated party) upon termination of employment. These often specify a repurchase price, which might be the original acquisition price, book value, or a formula-based value.

The Tension: A key legal tension arises between the flexibility of these contractual agreements and the formal statutory framework for transfer restrictions and approvals. Can a contractual repurchase agreement effectively bypass the company approval process? More critically, can a contractual agreement, especially one fixing the repurchase price potentially far below market value, be so restrictive that it violates fundamental principles of public policy (koujo ryozoku, Civil Code Art. 90)?

2. The Case Study: Tokyo District Court, April 25, 2024

The case involved a dispute between former employee-shareholders (Plaintiffs X1 and X2) and their former employer (Company Y), a non-public company without a board of directors whose articles restricted share transfers.

2.1. Factual Background

- Plaintiffs X1 and X2 joined Company Y and subsequently acquired shares at different times, paying specific prices per share (¥50,000 and later ¥75,000).

- Around the time of the second share acquisition, they signed a memorandum (oboegaki) which stipulated: "In the event that an employee shareholder who subscribed to said shares loses their employee status due to reasons such as retirement, Company Y shall repurchase all shares held by that employee at the price at which the employee acquired the shares." (Emphasis added). They signed similar memoranda upon subsequent share acquisitions (including via a transfer from another entity related to the representative director).

- Over the years, the company underwent stock splits and consolidations. Importantly, Company Y paid dividends to X1 and X2 during their tenure.

- After resigning, X1 and X2 sought Company Y's approval to transfer their shares (now reflecting the splits/consolidations) to an unrelated third party (Corporation D).

- Company Y refused approval and instead invoked the repurchase memorandum, tendering payment calculated based on the original acquisition prices per share for the total number of shares held by X1 and X2 at termination.

- X1 and X2 rejected this and filed suit.

2.2. The Legal Claims

The plaintiffs primarily argued:

- Invalid Scope of Agreement: The repurchase obligation in the memorandum only applied to the specific shares acquired around the time the memorandum was signed, not to all shares held at termination (including those acquired earlier or later, or resulting from splits/consolidations whose "identity" they claimed was lost).

- Violation of Public Policy (Civil Code Art. 90): The agreement forcing repurchase at the original acquisition price was void against public policy because it unreasonably restricted their ability to recover the capital invested and realize any appreciation in share value, effectively trapping their investment without a fair exit mechanism.

2.3. The Court's Decision

The Tokyo District Court dismissed the plaintiffs' claims, finding:

- Agreement Scope: The court interpreted the memorandum's reference to "all shares" (zenkabu) literally, concluding it applied to the entirety of the shares held by the employee at the time of termination, regardless of when or how they were acquired. It held that stock splits or consolidations did not extinguish this contractual obligation. An agreement covering all shares held at termination was deemed validly formed between the parties.

- No Violation of Public Policy: The court rejected the argument that the fixed acquisition price repurchase clause violated public policy. The crucial factor in the court's reasoning was that Company Y had paid dividends to the plaintiffs over several years. The court inferred from this history of dividend payments that the company did not have the intention of unreasonably restricting the employees' ability to recover their invested capital. Therefore, the restrictive repurchase price mechanism was deemed not to violate public policy in this specific context.

3. Analyzing the Court's Reasoning and Legal Debates

The court's decision touches upon several contentious areas in Japanese corporate law regarding closely-held companies.

3.1. Scope of the Repurchase Agreement

The court's broad interpretation of "all shares" held at termination seems textually plausible based on the memorandum's wording. The plaintiffs' argument that stock splits/consolidations legally altered the identity of the shares subject to the original agreement was rejected, aligning with the general principle that such corporate actions change the form but not the substance of share ownership rights.

3.2. Validity and Public Policy (Civil Code Art. 90)

This was the core legal battleground. The central question is whether an agreement forcing a shareholder to sell back shares at the original acquisition price constitutes an unreasonable restraint void under public policy.

- The Capital Recovery Principle: Japanese law, under the umbrella of public policy (Civil Code Art. 90), generally disfavors agreements that place excessive restrictions on economic freedom or unduly prevent the recovery of invested capital. Forcing a sale at potentially far below fair market value, denying any appreciation realized over years of employment and company growth, appears prima facie restrictive.

- The Court's Reliance on Dividends: The court's decision hinged significantly on the payment of dividends. It viewed the dividend stream as a form of return on investment that negated the argument that capital recovery was unreasonably restricted. This reasoning is debatable. While dividends represent a return, they do not typically substitute for the ability to realize capital gains upon exit, which is a primary expectation for equity holders. Does receiving dividends, regardless of their size relative to the potential appreciation, automatically make a fixed, potentially low, repurchase price "reasonable"? Academic commentary suggests this is a weak justification.

- Alternative Views and the Purpose of the Agreement: Many Japanese corporate law scholars argue that agreements forcing repurchase at acquisition cost are inherently problematic and potentially void against public policy. They argue such clauses can circumvent the statutory transfer approval process (which implicitly involves assessing fair price) and unfairly deny shareholders the economic upside of their investment. Such clauses might be upheld only if found reasonable based on specific circumstances, such as being part of a clearly defined Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) with genuine employee welfare objectives, or perhaps if coupled with exceptionally high dividend payouts that effectively compensate for the lack of capital gains. A crucial point, highlighted in commentary on this case, is that the court did not deeply analyze the purpose of the shareholding and the repurchase agreement. Was it intended purely as an incentive tied to employment, justifying clawback at cost? Or was it intended as a long-term investment opportunity for key employees, making the denial of appreciation seem less reasonable? The purpose could significantly impact the public policy assessment.

- Comparison with Prior Cases: Earlier lower court decisions (e.g., Kobe Dist. Ct. Amagasaki Branch, Feb 19, 1982; Kyoto Dist. Ct., Feb 3, 1989) had also considered dividend payments when upholding similar agreements, but often in the clearer context of structured ESOPs (juugyoin mochikabu seido). The specific nature and purpose of the shareholding arrangement in the April 2024 case seemed less defined, making the direct comparison potentially less compelling.

- Circumvention Concerns: A fundamental criticism of such agreements is that they can function as a de facto circumvention of the Companies Act's share transfer approval mechanism. The statutory process allows the company (or its designated purchaser) to buy the shares if it disapproves a transfer to a third party, but generally implies a negotiation towards a fair price (with recourse to court price determination if agreement fails - Art. 144). A pre-agreed repurchase at acquisition cost arguably sidesteps this potentially fairer process. The court did not engage deeply with this circumvention argument.

4. Implications for Businesses and Shareholders

The Tokyo District Court's decision, while specific to its facts, offers important points for consideration:

- For Businesses Drafting Agreements:

- Clarity is Key: Clearly define the scope of shares subject to repurchase (e.g., all shares held at termination vs. specific shares granted under a plan).

- Pricing Mechanism Risk: Relying solely on acquisition cost as the repurchase price carries legal risk. While dividends might be considered a mitigating factor by some courts, it's not a guaranteed defense against a public policy challenge. Consider alternative pricing: fair market value determined by appraisal, formula-based pricing (e.g., based on net assets or earnings multiples), or book value.

- Define the Purpose: Clearly articulating the purpose of the employee shareholding and the repurchase clause (e.g., incentive alignment, ensuring shares remain with employees, providing liquidity upon exit) may strengthen the argument for reasonableness.

- Consider Dividends: While not a panacea, a consistent history of meaningful dividend payments might support the argument that shareholders received a fair return, potentially weakening claims that capital recovery was unduly restricted.

- For Employee Shareholders:

- Understand the Terms: Carefully review any agreements signed when acquiring shares, particularly concerning repurchase obligations and pricing upon termination.

- Limitations on Value Realization: Recognize that fixed-price repurchase clauses, especially at acquisition cost, can severely limit the ability to profit from the company's growth.

- The Role of Dividends: Dividend payments are positive but may not fully compensate for the inability to sell at fair market value.

- Potential for Disputes: Be aware that invoking such clauses, especially when the acquisition price is significantly below current value, can lead to disputes and litigation.

Conclusion

The April 25, 2024, Tokyo District Court ruling offers a recent judicial perspective on the enforceability of contractual share repurchase agreements in Japanese closely-held companies, particularly fixed-price clauses tied to employee termination. The court upheld such an agreement, emphasizing the payment of dividends as evidence that the restriction on capital recovery was not unreasonable under public policy principles (Civil Code Art. 90).

However, the decision rests on contentious ground. Significant legal debate persists regarding the general validity and fairness of repurchase-at-acquisition-cost clauses, their potential to circumvent statutory protections, and whether dividend payments alone are sufficient to render them compliant with public policy. The purpose behind the shareholding arrangement and the repurchase clause appears to be a critical, yet sometimes overlooked, factor in assessing reasonableness.

This case underscores the complexities surrounding share transfer restrictions in non-public Japanese companies. Businesses seeking to control ownership through such contractual mechanisms must draft them with extreme care, weighing control objectives against the risk of legal challenges based on public policy. Employee shareholders, in turn, must be acutely aware of the potential limitations these agreements impose on their ability to realize the full economic value of their shares. While this District Court decision provides one data point, the precise balance between contractual freedom and the protection of shareholder economic interests in this context likely requires further clarification from higher courts in the future.

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan: Key Differences for U.S. Investors

- Mandatory Tender Offers in Japan: Expanded Scope under the 2024 FIEA Amendments

- Antitrust Oversight in Japanese M&A: Understanding Merger Control

- Ministry of Justice — FAQ on Share Transfer Restrictions (JP)

https://www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/minji07_00123.html