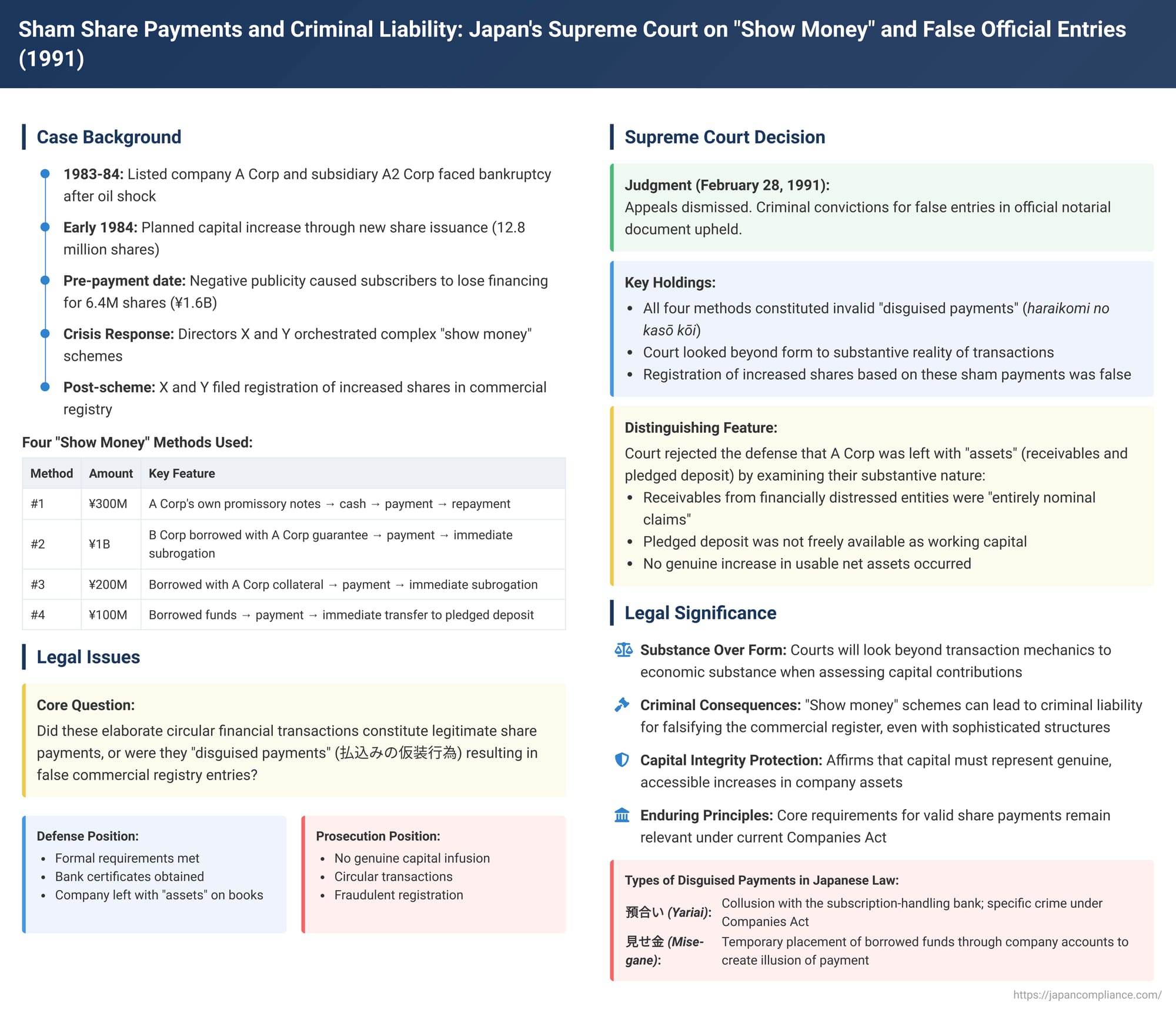

Sham Share Payments and Criminal Liability: Japan's Supreme Court on "Show Money" and False Official Entries

Judgment Date: February 28, 1991

When companies raise capital through new share issuances, the integrity of the payment process is paramount. Japanese law, like that in many jurisdictions, strictly scrutinizes transactions designed to merely create an illusion of payment without a genuine infusion of usable funds into the company. Such schemes, often termed "disguised payments" (払込みの仮装行為 - haraikomi no kasō kōi), can lead to severe consequences, including criminal liability for those involved in falsifying official corporate records. A 1991 Supreme Court of Japan decision delved into a complex case of "show money" (mise-gane - 見せ金), affirming that even sophisticated arrangements that leave a company with nominal "assets" can still be deemed criminally fraudulent if the underlying reality is a sham payment.

The Company's Crisis and the Desperate Capital Increase

The case involved A Corp, a company listed on the Second Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, which, along with its de facto subsidiary A2 Corp, found itself in severe financial distress following the oil shock. By the end of 1983, A Corp was on the brink of bankruptcy. To avert collapse, A Corp's Representative Director, X, and its Managing Director, Y (who also served as the Representative Director of A2 Corp), devised a plan in early 1984 to raise funds by issuing new shares through a third-party allotment.

However, the plan hit a major snag just before the scheduled payment date for the new shares. An industry newspaper published an article questioning the viability of this capital increase. This negative publicity caused two significant intended subscribers – A2 Corp (which was also to subscribe for some shares in the name of a nominal party, C) and another company, B Corp – to lose their financing. Consequently, they were unable to secure the funds for their allotted shares, which amounted to 6.4 million shares out of a total planned issuance of 12.8 million shares, representing ¥1.6 billion in subscription money. For a listed company in A Corp's precarious position, the failure of a major capital increase could trigger immediate bankruptcy.

Faced with this dire situation, X and Y orchestrated a series of complex transactions to create the appearance that the ¥1.6 billion subscription for these 6.4 million shares had been duly paid. These schemes involved four distinct methods:

- Method 1 (for 1.2 million shares subscribed by A2 Corp, value ¥300 million):

- A Corp issued two of its own promissory notes (one for ¥300 million, another for ¥200 million) to an entity D.

- D discounted these notes at a financial institution. From the discounted proceeds, D delivered ¥300 million in cash to A Corp (the remaining ¥200 million was, at the discounter's insistence, placed into a notice deposit account in D's name).

- A2 Corp then "borrowed" this ¥300 million from A Corp and formally paid it into A Corp's designated bank account as subscription money for the new shares.

- A Corp obtained a certificate from the bank confirming the deposit of share payment.

- Just four days later, A Corp used this deposited ¥300 million to settle its own ¥300 million promissory note that it had earlier issued to D as part of this circular flow of funds.

- Method 2 (for 4 million shares subscribed by B Corp, value ¥1 billion):

- B Corp borrowed ¥1 billion from E Corp (a finance company), with A Corp providing a joint guarantee for this loan.

- B Corp paid this borrowed ¥1 billion into A Corp's designated bank account as subscription money.

- A Corp obtained a certificate of deposit.

- Merely two days later, A Corp used this deposited ¥1 billion to make a "subrogated payment" (代位弁済 - dai-i bensai) on behalf of B Corp, effectively repaying B Corp's ¥1 billion loan to E Corp.

- Method 3 (for A2 Corp's remaining 800,000 shares, value ¥200 million):

- A Corp provided the ¥200 million notice deposit certificate (which was in D's name from Method 1) as collateral.

- A2 Corp then borrowed ¥200 million personally from F, who was the representative director of E Corp (the finance company involved in Method 2).

- Following a similar pattern, this ¥200 million was paid in as subscription money by A2 Corp, A Corp received a certificate of deposit, and then A Corp used these funds to make a subrogated payment of A2 Corp's ¥200 million personal loan to F.

- Method 4 (for 400,000 shares subscribed by A2 Corp in C's name, value ¥100 million):

- A2 Corp borrowed ¥100 million from H Insurance Co., with G Bank providing a joint guarantee.

- This ¥100 million was paid as subscription money into A Corp's account at G Bank's Ueno branch.

- A Corp obtained a certificate of deposit.

- Two days later, A Corp transferred this ¥100 million from the subscription account to an ordinary deposit account, immediately withdrew it by cheque, and then instantly redeposited it into a time deposit account at the very same G Bank branch. G Bank then established a pledge over this ¥100 million time deposit (presumably to secure its guarantee to H Insurance).

The Criminal Charge: Falsifying the Commercial Register

After these intricate transactions were completed, X and Y, in their capacity as directors of A Corp, submitted an application to the Legal Affairs Bureau to register the change in A Corp's total number of issued shares, reflecting the purported full subscription of the 12.8 million new shares. This act of causing the commercial register – an official notarial document – to record an increased number of issued shares (and by implication, an increase in paid-in capital) based on these sham payments led to criminal charges against X and Y. They were prosecuted for making false entries in an official notarial document (公正証書原本不実記載罪 - kōsei shōsho genpon fujitsu kisai zai) and for the use of such a falsified document, under Japan's Penal Code.

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court found X and Y guilty. They appealed their convictions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding Convictions by Piercing the Veil of Transactions

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated February 28, 1991, dismissed the appeals and upheld the convictions of X and Y. The Court's reasoning focused on the substantive reality of the transactions rather than their mere outward form:

- Orchestration and Lack of Genuine Intent (Methods 1-3): The Court found that the payment schemes for the shares subscribed under Methods 1, 2, and 3 were all orchestrated under the initiative of A Corp itself. From the outset, there was no genuine intention to secure actual, usable funds for the company through these share subscriptions. The nominal subscribers (A2 Corp and B Corp) used funds that were either sourced directly from A Corp or borrowed for a very short term with A Corp's backing, merely to create the superficial appearance of payment. A Corp then immediately retrieved these "paid-in" funds to settle the promissory notes used to generate the initial cash (Method 1) or to make subrogated payments for the loans taken out by the subscribers (Methods 2 and 3).

- Encumbered Funds (Method 4): The payment for the shares in Method 4 was also deemed a disguised payment driven by a similar lack of genuine intent to capitalize the company. Although a time deposit was technically created in A Corp's name, a pledge was simultaneously established over it by G Bank (which had guaranteed A2 Corp's loan from H Insurance). This pledge meant that A Corp could not freely use these funds as company capital unless and until A2 Corp independently repaid its underlying debt to H Insurance.

- Legal Invalidity of the Payments: Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that all four sets of transactions did not constitute valid payments for the new shares. The Court referenced one of its own prior civil case precedents (Supreme Court, December 6, 1963 – Case 7 in the user's context) which dealt with the invalidity of mise-gane payments.

- Nominal "Assets" vs. Substantive Capital: The Court acknowledged a potential distinction from "typical" mise-gane scenarios where money simply passes through the company's accounts and back to the lender, leaving nothing behind. In this case, as a result of these elaborate transactions, A Corp appeared to be left with certain "assets" on its books: specifically, a receivable of ¥1 billion from B Corp, receivables totaling ¥500 million from A2 Corp (¥300 million + ¥200 million), and the ¥100 million time deposit (albeit pledged).

However, the Supreme Court pierced through this appearance:- The receivables from B Corp and A2 Corp were, at the time, "entirely nominal claims in substance." Given the financial state of A2 Corp (A Corp's subsidiary) and the circular nature of the funding for B Corp (guaranteed by A Corp and immediately repaid by A Corp), these were not genuinely collectible assets that increased A Corp's real net worth.

- The ¥100 million time deposit, being pledged to G Bank and contingent upon A2 Corp (which was found to lack repayment ability) satisfying its debt to H Insurance, could also not be considered a "substantive asset" freely available to A Corp for its business operations.

- False Entry Confirmed: Since the payments for the new shares were deemed substantively invalid, the subsequent registration in the commercial register of an increased number of issued shares (and the corresponding increase in stated capital based on these sham payments) was indeed a false entry in an official document. The lower courts' guilty verdicts were therefore affirmed.

Understanding "Disguised Payments" in Japanese Corporate Law

This Supreme Court decision highlights the strict stance taken against schemes designed to circumvent capital contribution requirements. Two main types of "disguised payments" are often discussed:

- "Arranged Deposits" (Yariai - 預合い): This typically involves promoters or directors of a company borrowing funds from the bank that is designated to handle share subscription payments. These borrowed funds are then temporarily deposited into the company's account as if they were share payments, with an understanding that the company will not withdraw these funds until the initial loan from the bank is repaid. If this involves collusion with bank officials, it can be a specific crime under the Companies Act (Article 965).

- "Show Money" (Mise-gane - 見せ金): This is a more common method, often developed to avoid the stricter rules against yariai. It involves borrowing funds from a third party (other than the subscription-handling bank), paying these funds into the company's account to simulate share payment, obtaining the necessary certificates, and then immediately withdrawing the funds after the company's incorporation or the new share issuance is registered to repay the original lender. The funds make only a fleeting appearance in the company's accounts.

Under the Commercial Code (in effect at the time of this case), both yariai and mise-gane were generally considered by prevailing legal theory and case law to result in invalid share payments from a civil law perspective. The core issue is that no real, lasting economic resources are contributed to the company.

The criminal offense of making a false entry in an official notarial document (Penal Code Article 157, Paragraph 1) aims to protect public trust and reliance on the accuracy of official records like the commercial register. If a company's directors, knowing that share payments were merely disguised and not genuine, cause the commercial register to reflect an increased number of issued shares or an inflated capital amount, they can be held criminally liable.

Analysis and Implications

This 1991 Supreme Court ruling carries several important implications:

- Substance Over Form in Assessing Capital Contributions: The decision powerfully reaffirms that courts will look beyond the superficial mechanics of financial transactions to their underlying economic substance when assessing the validity of share payments and the truthfulness of related corporate registrations. The mere circulation of funds or the creation of encumbered or uncollectible "assets" does not constitute a genuine capital contribution.

- Criminal Consequences of Mise-gane: The case firmly establishes that mise-gane schemes, even if they differ from "typical" textbook examples by leaving behind nominal receivables or restricted assets, can lead to criminal convictions for falsifying the commercial register if the net result is that the company has not actually received new, usable capital corresponding to the registered increase in shares.

- The Capital Adequacy Principle and Creditor Protection: While the direct legal basis for the criminal charge is the falsity of the registration, the underlying concern relates to the integrity of the company's stated capital. The "capital adequacy principle" (shihon jūjitsu no gensoku) traditionally aims to ensure that a company actually possesses the capital it claims to have, partly for the protection of creditors and to maintain market confidence. Disguised payments directly undermine this principle. Even if modern interpretations of the Companies Act sometimes de-emphasize the direct creditor protection role of capital rules in favor of shareholder-focused concerns (like preventing unfair value shifts), the public representation of capital in the commercial register remains a matter of significant public interest, and its accuracy is protected by criminal law.

- Continuing Relevance: Although this case was decided under the old Commercial Code, its principles regarding the substantive assessment of disguised payments and the criminal liability for false registration remain highly relevant under the current Companies Act. While the Companies Act introduced specific provisions for dealing with certain types of disguised contributions at the time of company formation (e.g., Article 52-2), the general invalidity of mise-gane in the context of subsequent capital increases and the potential for criminal charges for false registration persist. The core requirement is that paid-in capital must represent a real and accessible increase in the company's net assets.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1991 decision in this "show money" case serves as a stark reminder of the serious legal repercussions of attempting to inflate a company's capital through sham transactions. The Court demonstrated its willingness to scrutinize complex financial maneuvers and to hold corporate directors criminally liable if they cause false information about share payments and capital to be entered into official public records. The judgment underscores the fundamental legal expectation that capital contributions must be genuine and result in a substantive increase in the company's usable assets, not merely a temporary illusion created for deceptive purposes. It affirms that the integrity of the commercial register and the underlying reality of corporate capitalization are matters vigorously protected by Japanese law.