Sham or Substance? 1967 Japanese Supreme Court on Collusive Share Payments and Employee Subscriptions

Date of Judgment: December 14, 1967

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

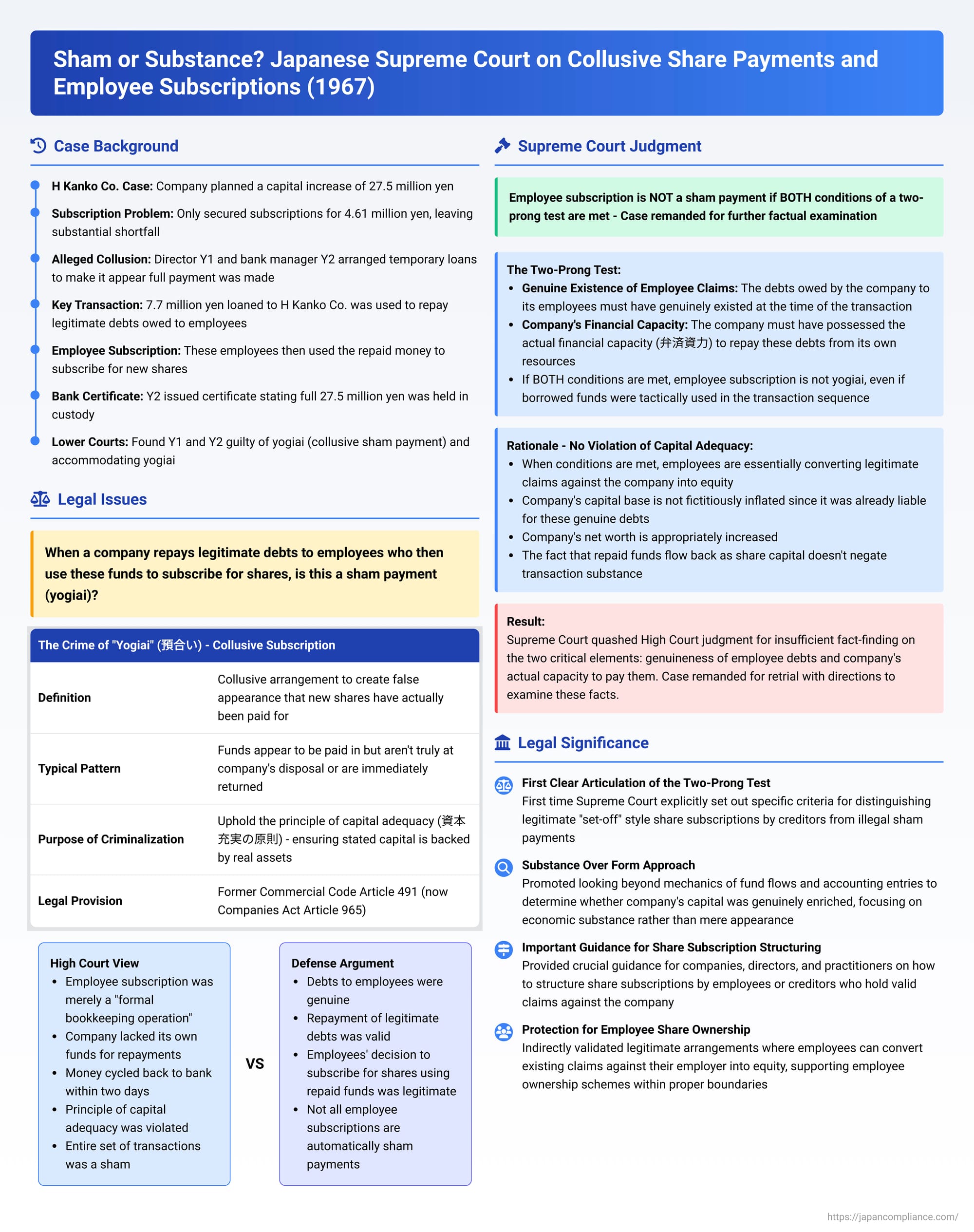

Ensuring that a company genuinely receives the capital for which its shares are issued is a cornerstone of corporate integrity and creditor protection. Japanese company law has long criminalized practices designed to create a false appearance of share payment. One such offense is "yogiai" (預合い), a collusive arrangement, typically between company directors and the bank handling share subscriptions, to disguise the fact that new shares have not actually been paid for, or that the funds are merely circulated without truly enriching the company.

A complex scenario arises when a company, seeking to increase its capital, borrows funds, uses those funds to repay pre-existing, legitimate debts owed to its own employees, and these employees then use the repaid money to subscribe to the company's new shares. Is this a legitimate series of transactions, or does it fall under the ambit of a prohibited sham payment? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this nuanced question in a significant decision on December 14, 1967.

The Crime of "Yogiai" (Collusive Subscription) and the Principle of Capital Adequacy

"Yogiai" (and the corresponding offense of "ō-yogiai" or accommodating yogiai, applicable to the bank involved) under Japan's then Commercial Code (Article 491, principles now in Companies Act Article 965) essentially refers to a conspiracy to create a facade of capital payment. This typically involves:

- Collusion between the company's directors and the financial institution handling the share issue.

- An arrangement where funds are made to appear as paid-in capital for new shares, but these funds are either not genuinely at the company's free disposal, are immediately returned to the lender, or the "payment" is otherwise fictitious.

The primary purpose of criminalizing yogiai is to uphold the "principle of capital adequacy" (資本充実の原則 - shihon jūjitsu no gensoku). This principle demands that the company's stated capital is backed by real assets, providing a degree of security for creditors and reflecting the true financial state of the company. Sham payments undermine this by creating a misleading picture of the company's capitalization.

The H Kanko Co. Capital Increase Case

The case before the Supreme Court involved H Kanko Co., its director Y1 (Mr. Goto Yusuke), and Y2 (Mr. Yoshida Takashi), the branch manager of T Bank, which was handling H Kanko Co.'s new share issue.

- Subscription Shortfall: H Kanko Co. planned a capital increase of 27.5 million yen but only managed to secure subscriptions for 4.61 million yen, leaving a substantial shortfall.

- The Alleged Collusion: To make it appear as though the entire capital increase was successful, Y1 (the director) and Y2 (the bank manager) allegedly colluded. The bank provided temporary loans to H Kanko Co. (7.7 million yen) and to H Kanko Co.'s representative director, Mr. I.F. (15 million yen). These borrowed funds were then routed through the bank's books to appear as if they were payments for the unsubscribed shares. The understanding was that these loans would be repaid almost immediately from these "custody funds" once the capital increase registration process was completed. Based on this arrangement, Y2 issued an official certificate stating that the full 27.5 million yen for the new shares was being held in custody by the bank.

- The Employee Subscription Element – The Crux of the Dispute: A specific portion of the loan made to H Kanko Co. itself (the 7.7 million yen) was accounted for in a particular way. This sum was, on paper, used by H Kanko Co. to repay pre-existing, legitimate debts that the company owed to its employees (these debts totaled approximately 6.37 million yen, with the remainder of the 7.7 million yen used to repay a debt to the representative director). These employees then formally used this "repaid" money—in some cases supplemented by small additional loans from H Kanko Co.—to subscribe and pay for new shares in the capital increase.

- Lower Court Rulings: The first instance court and the High Court found both Y1 and Y2 guilty of yogiai and accommodating yogiai, respectively. They viewed the entire set of transactions, including the employee subscription part, as a sham designed merely to create the appearance of full payment. The High Court specifically rejected the defense argument that the employee-related transactions were legitimate, stating that it was merely a "formal bookkeeping operation to disguise payment" because the company lacked its own funds for such repayments and the money essentially cycled back to the bank within two days, thus ignoring the principle of capital adequacy.

The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 14, 1967)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for a retrial, finding that the lower courts had not adequately examined the critical factual elements concerning the employee subscriptions.

Need for Careful Scrutiny of Substantive Payment

The Court began by emphasizing that because sham payments can easily be disguised through accounting entries, courts must conduct a very careful and thorough examination to determine whether a substantive payment for shares has genuinely occurred. One should not be misled by mere bookkeeping operations.

The Two-Prong Test for the Validity of Employee "Set-Off" Style Subscriptions

The Supreme Court then laid down a crucial two-prong test to determine whether the specific method involving the employees—where the company "repays" their existing debts and they use these funds to subscribe to shares—constitutes a legitimate payment or an illegal sham:

Such a method of payment is NOT a sham payment (and therefore does not constitute yogiai) if both of the following conditions are met:

- Genuine Existence of Employee Claims: The debts owed by the company to its employees (which were purportedly repaid and then used for the share subscriptions) must have genuinely existed at the time of the transaction.

- Company's Financial Capacity to Pay These Debts: The company must have possessed the actual financial capacity (弁済資力 - bensai shiryoku) to repay these genuine debts to its employees from its own resources, even if it tactically chose to use borrowed funds as part of the overall transaction sequence.

Rationale: No Violation of Capital Adequacy if Both Conditions Are Met

The Supreme Court reasoned that if these two conditions are satisfied, the company's capital base is not being fictitiously inflated. In such a scenario:

- The employees are, in substance, converting legitimate pre-existing claims against the company into equity.

- The principle of capital adequacy is not violated because the company was already genuinely liable for these debts and was capable of settling them. The fact that the repaid funds immediately flowed back to the company as share capital does not negate the substance of the transaction if the underlying debts owed to the employees were real and the company had the means to pay them. The company's net worth is appropriately increased.

Lower Courts' Error in Fact-Finding

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred by convicting the defendants without properly investigating and making findings on these two critical factual elements: the genuineness of the debts owed to the employees and H Kanko Co.'s actual financial capacity to pay those debts at that time. The lower courts had too readily dismissed the employee-related part of the transaction as a mere "formal bookkeeping operation" without delving into these substantive prerequisites.

Outcome: Due to this failure to fully examine the essential facts related to the employee subscriptions under the newly articulated two-prong test, the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment. The case was remanded to the Osaka High Court for a retrial, with specific instructions to ascertain these facts before determining whether the crime of yogiai had been committed with respect to that portion of the funds.

Significance of the Ruling

The 1967 Supreme Court decision in the H Kanko Co. case was a landmark judgment for several reasons:

- First Clear Articulation of the Two-Prong Test: It was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly set out these specific criteria (genuine pre-existing debt owed by the company to the subscriber, and the company's actual capacity to pay that debt) for distinguishing between a legitimate "set-off" style share subscription by creditors (such as employees) and an illegal sham payment constituting yogiai.

- Emphasis on Substantive Capital Contribution: The ruling strongly promoted a "substance over form" approach in assessing yogiai. It directed courts to look beyond the mechanics of fund flows and accounting entries to determine whether the company's capital was genuinely and substantively enriched, or merely made to appear so through deceptive practices.

- Important Guidance for Structuring Share Subscriptions: This decision provided crucial guidance for companies, their directors, and legal practitioners on how to structure share subscriptions by employees or other creditors who also hold valid claims against the company. It showed a legitimate pathway, provided the underlying conditions of genuine debt and company solvency were met.

- Protection for Legitimate Employee Share Ownership Schemes: Indirectly, the ruling helps to protect and validate legitimate arrangements where employees might convert existing claims against their employer (such as unpaid wages, loans made to the company, or other recognized debts) into equity in the company.

Conclusion

The 1967 Supreme Court decision concerning H Kanko Co. brought important clarity and a more nuanced, substantive approach to the interpretation of "yogiai" (collusive sham share payments) under Japanese company law. While unequivocally condemning outright fictitious payments designed to deceive and undermine capital adequacy, the Court also recognized that not all indirect or set-off style subscription methods are inherently illegal.

Specifically, the ruling established that if a company repays genuine, pre-existing debts to its employees (and critically, has the actual financial capacity to make such repayments), and those employees then use these legitimately received funds to subscribe to new shares, such a transaction does not necessarily constitute a criminal sham payment. This decision underscores the importance of a meticulous factual inquiry into the bona fides of the underlying claims and the company's true financial ability before concluding that an arrangement violates the vital principle of capital adequacy and constitutes the serious offense of yogiai.