Sham Lawsuits and Shareholder Rights: Japan's Supreme Court on Retrials of New Share Nullifications

Date of Judgment: November 21, 2013

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

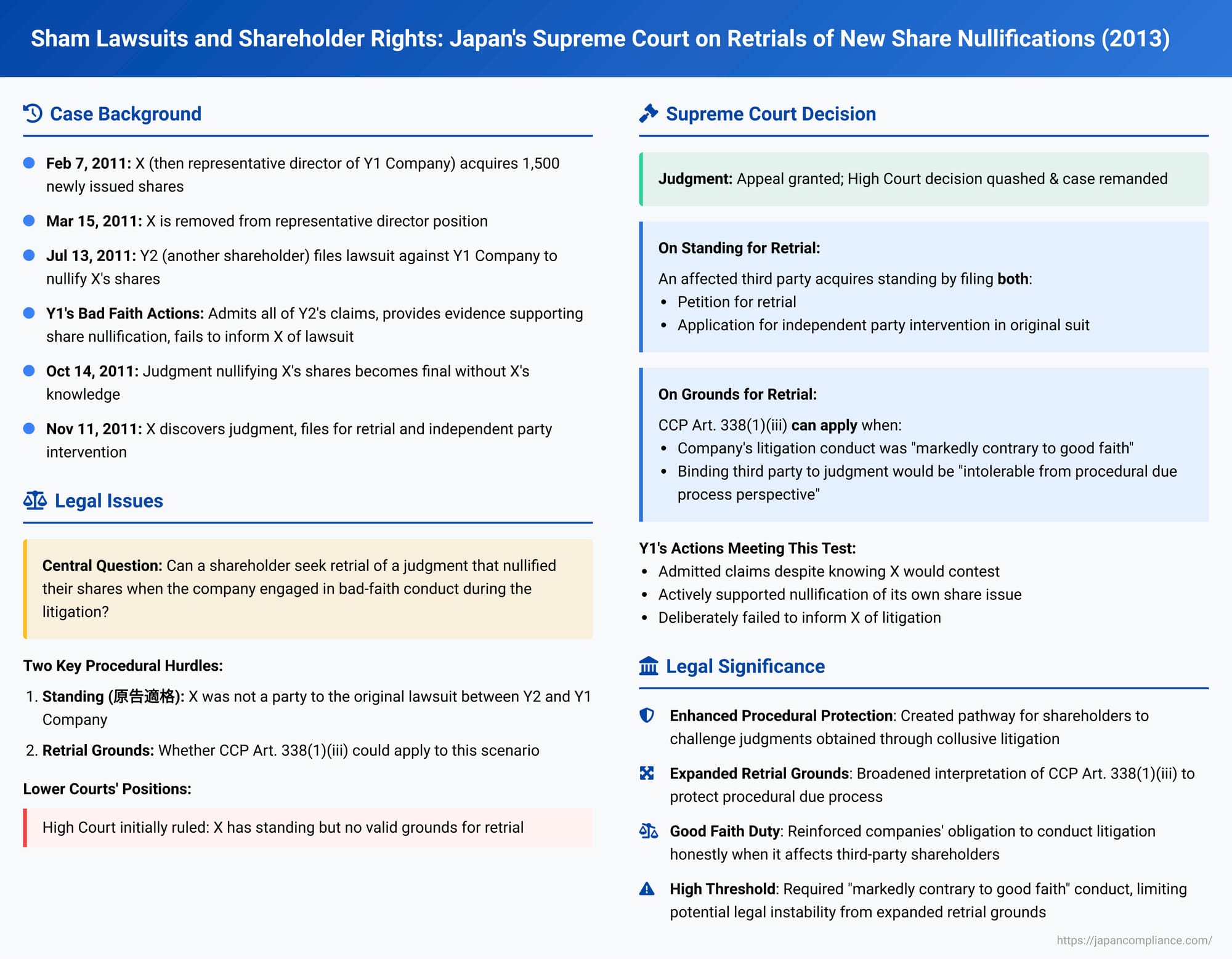

The issuance of new shares by a company is a fundamental corporate action. However, the validity of such an issuance can sometimes be challenged by existing shareholders. Imagine a scenario where new shares are issued to an individual, but another shareholder sues the company to nullify this issuance. What happens if the company, instead of defending the validity of its own share issue, effectively sides with the challenger, or even actively helps to have the shares nullified, all without the knowledge of the person who received those new shares? If a judgment nullifying the shares is finalized under such circumstances, is the new shareholder left without recourse?

This complex intersection of corporate law, procedural fairness, and the principles of good faith litigation was at the heart of a landmark decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on November 21, 2013. The Court addressed whether a shareholder, whose newly acquired shares were nullified by a judgment obtained in a suit where the company engaged in bad-faith conduct, could seek a retrial of that judgment.

The Background: A Disputed Share Issue and a "Prior Suit"

The case revolved around an individual, X, who had acquired newly issued shares in Y1 Company, and another shareholder of Y1, named Y2.

- The Share Issue: On February 7, 2011, Y1 Company issued 1,500 common shares to X following X's exercise of new share subscription rights. At that time, X was the representative director of Y1 Company but was subsequently removed from this position on March 15, 2011.

- The Dispute Begins: Following X's removal, Y1 Company sent a notice to A (a pledgee of X's shares in Y1) alleging that the share issue to X was invalid due to mise-gane – a term referring to a sham capital contribution where funds are merely shown for appearance but not genuinely paid into the company. X and A disputed this allegation, asserting the validity of the share issue.

- The "Prior Suit" (Zenso): On July 13, 2011, Y2, another shareholder of Y1 Company, initiated a lawsuit against Y1 Company. Initially, Y2 sought a declaratory judgment confirming the non-existence of the share issue to X. Later, Y2 added an alternative claim seeking the outright nullification of the share issue, again based on the allegation of mise-gane.

- Y1 Company's Conduct in the Prior Suit: Y1 Company's behavior in this litigation was highly unusual for a defendant company whose own share issuance was being challenged:

- At the first court hearing, Y1 Company formally admitted Y2's claim and all factual allegations supporting it.

- When the court, after reviewing initial evidence, directed Y1 Company to provide further proof regarding the mise-gane allegations, Y1 Company complied by submitting a written statement detailing the supposed sham transaction, effectively bolstering Y2's case against its own share issue.

- Crucially, Y1 Company was aware that X (the recipient of the shares) would strongly contest any attempt to nullify the share issue. Despite this, and despite it being easy to do so, Y1 Company did not inform X that the prior suit was pending.

- Outcome of the Prior Suit: On September 27, 2011, the court in the prior suit issued a judgment nullifying the share issue to X. This judgment became final and binding on October 14, 2011.

- X's Discovery and Subsequent Actions: X only learned of the prior suit and the subsequent judgment on October 19, 2011. In response, on November 11, 2011, X took two significant legal steps:

- X applied for "independent party intervention" (独立当事者参加 - dokuritsu tōjisha sanka) in the now-concluded prior suit, seeking to assert rights as a party with an independent interest.

- X filed a petition for a retrial (再審の訴え - saishin no uttae) of the prior judgment that had nullified X's shares.

The Legal Labyrinth: Standing and Grounds for Retrial

X faced two major legal hurdles in seeking to overturn the prior judgment:

1. Standing to Request a Retrial

Ordinarily, only the original parties to a lawsuit can request a retrial. X was not a named party in the prior suit between Y2 and Y1 Company. However, judgments in certain types of corporate lawsuits, such as those nullifying a new share issue, have an erga omnes effect (対世効 - taiseikō), meaning they are binding on all persons, including X, even if they were not direct participants.

The Supreme Court had to determine if, and how, a third party like X, who is bound by such a judgment, could acquire the necessary legal standing (原告適格 - genkoku tekikaku) to initiate a retrial. The High Court (the lower appellate court in this instance) had found that X had standing because X was affected by the judgment and could have participated via a co-litigant-type auxiliary intervention. However, the Supreme Court took a more nuanced approach to standing in the retrial context itself.

2. Grounds for Retrial

Even if standing could be established, X needed to demonstrate valid grounds for a retrial as stipulated by law. The Japanese Companies Act, while providing for the erga omnes effect of such judgments, did not explicitly list retrial grounds for organizational lawsuits like the nullification of a new share issue. Article 853 of the Companies Act detailed retrial grounds primarily for suits pursuing executive liability, which was not the case here.

X sought to rely on Article 338, Paragraph 1, Item (iii) of the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP). This provision traditionally covers retrial grounds related to defects in legal representation, such as when a party was represented by someone lacking the necessary authority, or when a person lacking legal capacity participated without a proper legal representative. On its face, X's situation – being an unnotified third party whose shares were nullified due to the company-defendant's actions – did not fit neatly into these established categories. The lower court, in fact, had previously suggested that such "fraudulent judgments" (sagai hanketsu) could not be recognized as an independent ground for retrial if not explicitly provided by law.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision of November 21, 2013

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, quashed the High Court's ruling (which had dismissed X's appeal regarding retrial grounds) and remanded the case for further consideration. The Supreme Court's reasoning provided crucial clarifications on both standing and the grounds for retrial in such exceptional circumstances.

On Standing to Request a Retrial

The Supreme Court first addressed, ex officio (on its own initiative), the issue of X's standing for a retrial. It reasoned that:

- A third party affected by a judgment nullifying a new share issue, merely by filing for a retrial, does not automatically gain standing. This is because, not being a party to the original concluded suit, they cannot directly undertake procedural acts concerning the substance of that original case even if a retrial were granted.

- However, the situation changes if the affected third party, in addition to filing for a retrial, also applies for independent party intervention in the original lawsuit. If a retrial is granted, the original case is reopened. This revived litigation provides the necessary "pending litigation" status for the independent party intervention to proceed. Through this intervention, the third party can then participate substantively and potentially influence the judgment.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that an affected third party (like X) acquires standing to pursue a retrial of the judgment by coupling the retrial petition with an application for independent party intervention in the original suit that produced the judgment.

- The Court noted that the High Court had erred by simply assuming X's standing based on being an affected party who could have made an auxiliary intervention, without properly considering the critical role of the independent party intervention application in the context of seeking a retrial.

On the Grounds for Retrial – An Expansive Interpretation of CCP Art. 338(1)(iii)

This was the most groundbreaking part of the decision. The Supreme Court acknowledged that:

- Under the Companies Act (Article 834, Item (ii)), only the issuing company itself has defendant standing in a suit to nullify a new share issue.

- Consequently, the mere fact that an affected third party (like X) was unaware of such a suit or was not given an opportunity to participate would not, in itself, automatically constitute a ground for retrial under CCP Art. 338(1)(iii).

However, the Court then introduced a critical qualification based on fundamental principles of procedural justice:

- Overriding Duty of Good Faith: Parties in civil litigation have a duty to act in good faith (CCP Art. 2). The Supreme Court emphasized that a company defending a suit to nullify its own share issue is, in a practical sense, also acting in a position that affects the interests of third parties who received those shares. This places a heightened duty on the company to conduct its litigation activities in good faith, with due consideration for the interests of these affected third parties.

- Procedural Due Process Concerns: It would be intolerable from a procedural due process standpoint if a third party were irrevocably bound by a judgment when the company’s conduct in the litigation was fundamentally flawed.

- The Key Test for Retrial Grounds: The Supreme Court established a specific test: If the company's litigation activities were markedly contrary to the principle of good faith (shingisoku), and if extending the effects of the final judgment to the affected third party would be unacceptable from a procedural due process perspective, then the said final judgment does indeed have grounds for retrial under CCP Art. 338, Paragraph 1, Item (iii).

Applying this test to Y1 Company's conduct in the prior suit:

- Y1 Company was fully aware that X would vigorously contest any attempt to nullify the share issue.

- Despite this knowledge, Y1 Company not only failed to contest Y2's lawsuit but actively supported Y2's claims by submitting evidence that purportedly demonstrated the invalidity of its own share issuance.

- Y1 Company, although easily able to do so, failed to inform X about the pending litigation, thereby depriving X of any opportunity to intervene or defend his interests.

- The Supreme Court concluded that this entire course of conduct by Y1 Company, as the statutorily designated sole defendant, provided sufficient basis to consider that its actions were "markedly contrary to good faith." Consequently, binding X to the prior judgment obtained under these circumstances was potentially "intolerable from a procedural due process perspective."

- Thus, the Court found that there was "room to see" (a possibility) that grounds for retrial under CCP Art. 338(1)(iii) existed in X's case.

The High Court had erred by not thoroughly examining the case from this perspective and prematurely denying the existence of retrial grounds.

Significance of the Ruling

This 2013 Supreme Court decision has profound implications for corporate litigation and shareholder protection in Japan:

- Enhanced Procedural Protection for Affected Third Parties: It provides a crucial, albeit specific, avenue for shareholders whose rights are extinguished by judgments obtained through collusive or bad-faith litigation by the company, especially when they were not parties to that original litigation.

- Expansive Interpretation of Retrial Grounds: The decision significantly broadens the traditional scope of CCP Art. 338(1)(iii). While the article's text focuses on defects in representation, the Supreme Court extended its application to situations involving severe procedural due process violations stemming from a party's egregious bad-faith conduct. This move was described in commentary as part of a trend to expand this provision to cover deficiencies in procedural guarantees.

- Reinforcing the Duty of Good Faith in Litigation: The ruling sends a strong message about the serious consequences for companies that fail to conduct litigation honestly and with appropriate regard for the interests of all stakeholders significantly affected by the outcome, particularly when the company is the sole statutory defendant in a suit with erga omnes effects.

- Clarification on Retrial for Organizational Suits: The decision effectively opened a path for retrials in certain corporate organizational lawsuits where the Companies Act itself was silent on the matter, by leveraging the Code of Civil Procedure.

- Potential for Legal Instability?: Academic commentary has noted a potential concern arising from this expansive interpretation. Retrials based on CCP Art. 338(1)(iii) in its traditional application (e.g., lack of proper representation) are not subject to the usual statutory time limits for initiating a retrial (CCP Art. 342(3)). If this lack of time limit were to apply broadly to these newly recognized grounds, it could potentially lead to delayed challenges against judgments that have erga omnes effect, thereby creating a degree of legal instability. However, the exceptionally high bar set by the Supreme Court—requiring conduct "markedly contrary to good faith" and an outcome "intolerable from a procedural due process perspective"—may naturally limit the number of cases that can meet this stringent test.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of November 21, 2013, is a powerful affirmation of procedural fairness and the paramount importance of good faith in the conduct of corporate litigation. It carefully carves out a pathway for shareholders to challenge judgments nullifying their shares when those judgments are the product of the company's own egregious bad faith and a lack of due process for the affected shareholder. By linking standing for retrial to independent party intervention and by creatively expanding the application of existing Code of Civil Procedure provisions, the Court ensured that the erga omnes effect of judgments in corporate organizational suits does not inadvertently become a shield for injustice procured through collusive or fundamentally unfair litigation practices. This ruling serves as both a critical safeguard for shareholder rights and a stern reminder to corporate litigants of their procedural obligations.