Settling with One Joint Tortfeasor: How Victim's Intent Shapes Reimbursement Rights in Japan

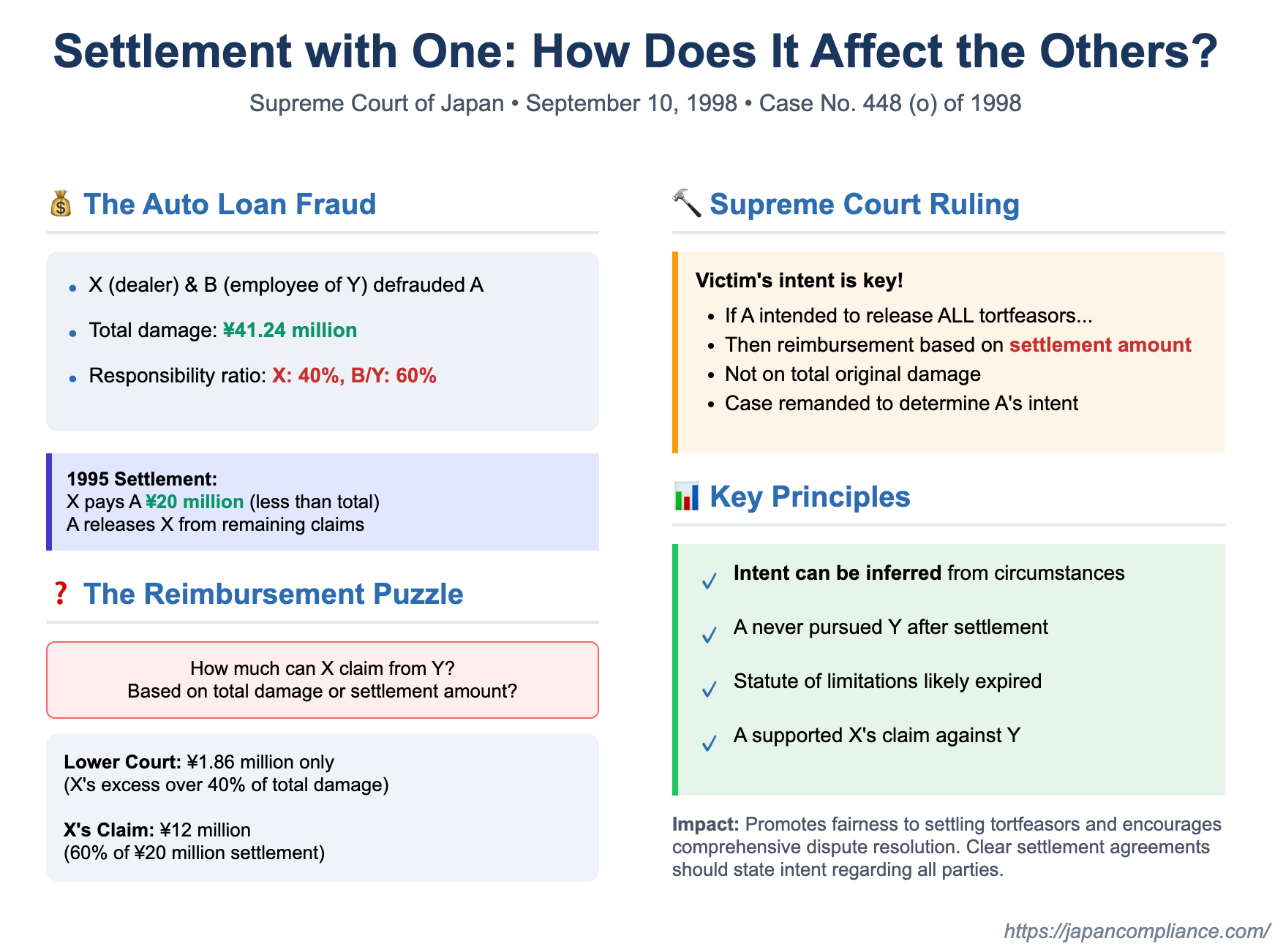

When multiple parties are responsible for causing harm as joint tortfeasors, the victim can typically seek full compensation from any one of them. If one tortfeasor pays the victim, they generally have a right to seek contribution or reimbursement (kyūshō) from the other tortfeasors for their respective shares of the liability. But what happens when the victim settles with and releases one tortfeasor for an amount less than the total damage? How does this affect the other tortfeasors, and critically, how is the reimbursement calculated? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled these complex questions in a significant judgment on September 10, 1998 (Heisei 9 (O) No. 448).

Joint Torts, Shared Responsibility, and the Basics of Reimbursement

In cases of joint torts, each wrongdoer is typically jointly and severally liable to the victim for the full extent of the damages. Internally, however, the tortfeasors often have an "apportionment of responsibility" or "burden share" based on their relative culpability or causal contribution to the harm. If one tortfeasor pays the victim an amount that exceeds their own internal share of the total damages, they can usually claim reimbursement from the other tortfeasors for the amounts attributable to those others' shares.

The Facts of the Case: An Auto Loan Fraud and a Partial Settlement

The 1998 case arose from an auto loan fraud scheme with the following key players:

- A: A finance company (the victim, referred to as Jaccs in the underlying proceedings, but not a party to this specific Supreme Court appeal).

- X: An auto dealer who was one of the perpetrators of the fraud (the plaintiff/appellant in this reimbursement action). X had a business agreement with A to broker auto loan contracts.

- B: An employee of company Y, who directly participated in the fraud with X.

- Y: The employer of B (the defendant/appellee in this reimbursement action), liable for B's actions under principles of vicarious liability (shiyōsha sekinin).

The Fraud and Initial Liability: B, needing to conceal fictitious car sales, enlisted X's help. Between 1988 and 1989, they facilitated numerous fictitious auto loan contracts between A and bogus car buyers, through which X and B improperly obtained approximately 33.03 million yen from A. As a result, X and B became jointly and severally liable to A for the tort. Y, as B's employer, was also liable to A. The internal responsibility ratio between X and B (and thus effectively between X and Y for reimbursement purposes) was determined to be 4:6 (X being 40% responsible, B/Y being 60% responsible).

A's Lawsuit and Settlement with X: In 1990, A sued X for damages. In January 1995, A and X reached a court-mediated settlement (soshōjō no wakai). Under this settlement:

- X acknowledged liability and paid A 20 million yen.

- A, in return, waived or released (hōki) its remaining claims against X.

At the time of this settlement, A's total quantifiable damages (including interest) were estimated to be around 41.24 million yen, significantly more than the 20 million yen X paid.

X's Claim for Reimbursement from Y: Having paid the 20 million yen, X then sued Y (as B's employer) seeking reimbursement of 16 million yen.

The Lower Courts' Dilemma: Reimbursement Based on Total Loss or Actual Settlement?

The lower courts struggled with how to calculate the reimbursement owed by Y to X:

- The first instance court awarded X only 1.86 million yen. It calculated X's 40% share of A's total loss (approx. 16.50 million yen of the 41.24 million yen), subtracted this and another unrelated contractual penalty X owed A from the 20 million yen X paid, and allowed reimbursement only for this small "excess" amount.

- X appealed, arguing that the reimbursement should be based on Y's 60% share of the 20 million yen settlement amount X actually paid, not on A's total original loss. X contended that the settlement with A was intended to be a comprehensive resolution.

- The appellate court dismissed X's appeal. It reasoned that a release granted by A to X would not automatically release Y from A's claims (due to rules on "impure" joint and several liability). If A could still theoretically pursue Y for Y's share of the remaining damages, then X's reimbursement from Y should still be based on X having paid more than X's share of the total damage.

X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clarification: Victim's Intent is Key

The Supreme Court partially overturned the appellate court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration, laying down important principles:

- General Reimbursement Rule (Reaffirmed): The Court first reiterated the established principle: if one joint tortfeasor (e.g., X) pays compensation to the victim that exceeds their own apportioned share of the total damage, they can seek reimbursement from another joint tortfeasor (e.g., Y) for that other tortfeasor's share of the liability.

- No Automatic Release for Other Tortfeasors (Pre-2017 Context): The Court acknowledged that under the law then applicable to "impure" joint and several liabilities (like those of joint tortfeasors), a release granted by the victim to one tortfeasor (X) did not automatically extend to release other tortfeasors (Y). This is because the rule of "absolute effect" of release applicable to "true" joint and several debts (former Civil Code Art. 437) did not apply.

- Crux of the Decision – The Effect of the Victim's Intent to Release All:

- The Supreme Court stated that if it is found that the victim (A), at the time of settling with and releasing one tortfeasor (X), also possessed the intention to release the other joint tortfeasor(s) (Y) from their remaining debt, then the effect of this release does extend to those other tortfeasors.

- Calculating Reimbursement in Such Cases: When the other tortfeasor (Y) is also effectively released by the victim (A) and no longer faces potential claims from A, the amount of reimbursement the settling tortfeasor (X) can claim from Y should be calculated based on the actual amount paid by X in the settlement. This settlement sum is treated as the "confirmed loss amount" for the purpose of inter-tortfeasor reimbursement, and it is then apportioned according to their respective shares of responsibility.

- Application to the Case and Remand:

- The Supreme Court noted that while the settlement document between A and X might not have explicitly stated A's intent regarding Y, there were surrounding circumstances to consider. For example, A had not subsequently pursued Y for any remaining debt, and the statute of limitations for A's claim against Y had likely expired by the time of the A-X settlement. Furthermore, there were indications that A was supportive of X's reimbursement action against Y.

- These factors, the Court found, suggested that A might have intended the settlement with X to be a comprehensive resolution of the entire fraud incident, thereby including an intention to release Y as well.

- The appellate court had erred by not investigating this crucial issue of A's intent to release Y.

- The Supreme Court calculated that if A did intend to release Y, and the 20 million yen settlement amount paid by X was used as the basis for reimbursement, X's 40% share would be 8 million yen. Therefore, X could potentially claim 12 million yen from Y (Y's 60% share of the 20 million yen paid by X). The case was remanded for the lower court to determine A's actual intent.

Unpacking the "Victim's Intent" and Its Implications

This judgment provides critical guidance on the repercussions of settling with one of multiple wrongdoers.

- Fairness to the Settling Tortfeasor: The Supreme Court's approach ensures that a tortfeasor who cooperates and settles with the victim (potentially for a pragmatic sum that gives the victim a quicker, certain recovery) is not unfairly disadvantaged in seeking reimbursement. If the victim intends to resolve the entire matter through that settlement, it is logical to base inter-tortfeasor reimbursement on that settlement amount.

- Determining the Victim's Intent: The victim's intent to release all tortfeasors becomes a key factual question. As the Supreme Court indicated, this intent can be inferred not just from the explicit wording of a settlement agreement (which may be silent or ambiguous on the point) but also from surrounding circumstances, such as the victim's subsequent conduct towards other tortfeasors and the overall context of the settlement.

- Theoretical Basis: Legal scholars have discussed the theoretical basis for how a release explicitly given to one tortfeasor can extend its benefits to another. Theories include analogies to unauthorized agency (the settling tortfeasor acting implicitly for others, subject to their ratification) or principles similar to a contract for the benefit of a third party (where the other tortfeasors are beneficiaries of the victim's intent to release them).

- Practical Advice: The clearest path is for settlement agreements to explicitly state whether the victim's release of one tortfeasor is also intended to discharge the liability of other known tortfeasors. This clarity can prevent future disputes. A victim might be willing to provide such a comprehensive release to secure a definite, albeit partial, payment from one party, especially if pursuing others is uncertain or costly.

Impact of the 2017 Civil Code Reforms

The 2017 reforms to the Japanese Civil Code made significant changes to the general rules on joint and several liability. Notably:

- The "relative effect" of events like release was strengthened as the general principle (new Article 441), meaning that a release of one obligor generally does not affect others unless specific exceptions apply or there's a contrary intention.

- The rules for reimbursement for partial payment in general joint and several obligations were clarified (new Article 442, Paragraph 1), generally allowing reimbursement based on the other obligors' share of the amount actually paid.

While these reforms provide a new backdrop, the core issue addressed by the 1998 Supreme Court judgment—namely, the significance of the victim's specific intent to release all joint tortfeasors when settling with one, and the consequent calculation of reimbursement based on the settlement sum—remains highly relevant. Scholarly debate continues on precisely how the new general reimbursement rule in Article 442(1) applies to the specific context of joint tortfeasors, and whether different policy considerations (like robust victim protection) might still warrant specific approaches for tort scenarios. The 1998 ruling's emphasis on discerning and giving effect to the victim's broader settlement intentions offers an important equitable pathway.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1998 decision in this case underscores a vital principle in the complex interplay between victim compensation, settlements, and inter-tortfeasor reimbursement. It highlights that the victim's intention when settling with one wrongdoer can be pivotal. If a victim intends a settlement with one tortfeasor to be a complete resolution of the harm, effectively releasing all involved, then the reimbursement claims among the tortfeasors should be based on the actual settlement amount. This promotes fairness to the settling party and encourages comprehensive solutions to disputes arising from joint wrongdoing, while still requiring careful factual inquiry into the victim's true intentions.