Settling All Scores: Can Past Unpaid Marital Expenses Be Included in Divorce Property Division? A 1978 Japan Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: November 14, 1978

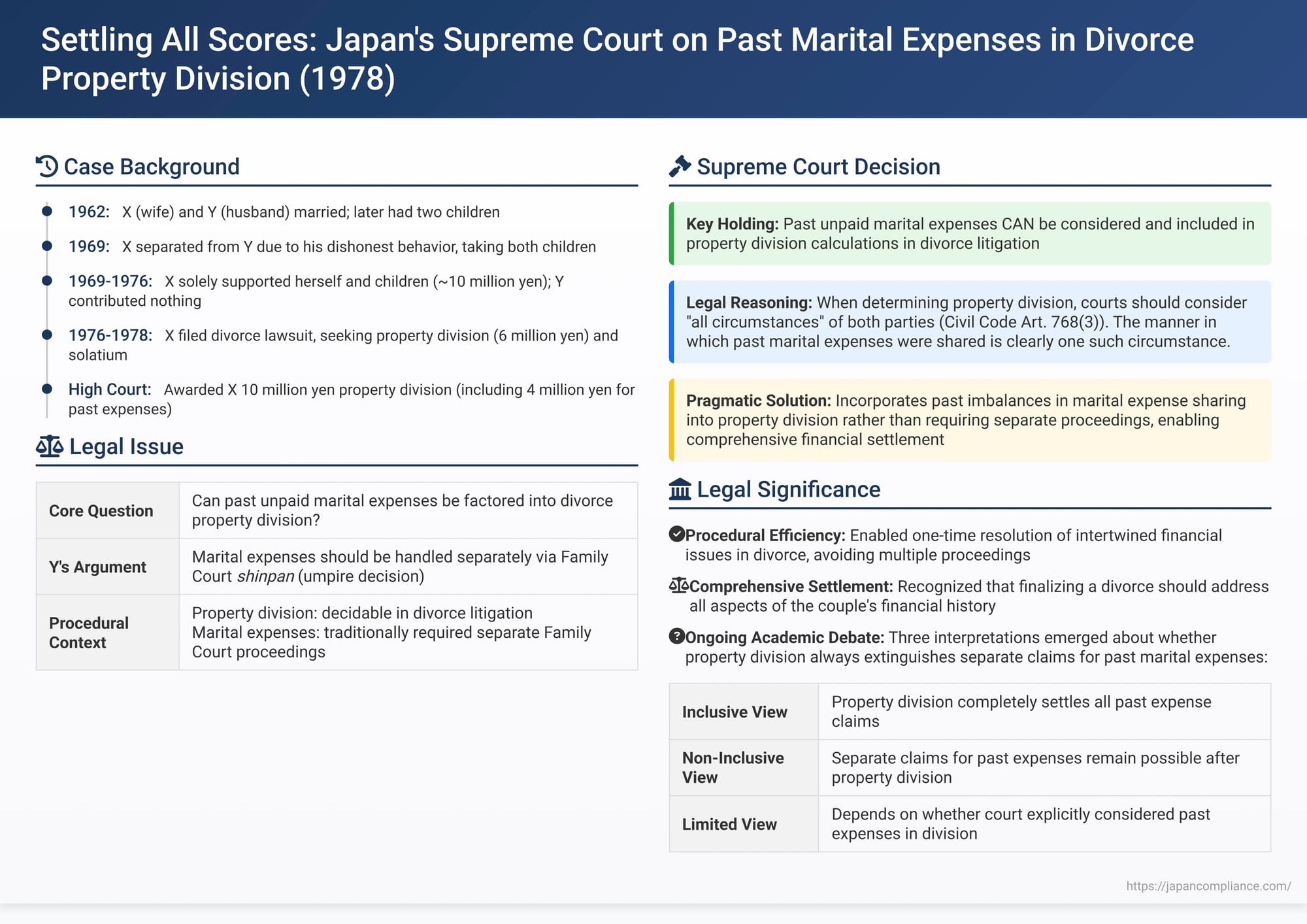

When a marriage ends in divorce in Japan, one of the critical financial processes is the division of marital property (財産分与 - zaisan bunyo). Separately, during the course of a marriage, spouses have a mutual obligation to share the expenses necessary for their communal life, including living costs and child-rearing expenses (婚姻費用 - kon'in hiyō). But what happens if, particularly during a period of separation leading up to the divorce, one spouse disproportionately shoulders these marital expenses because the other fails to contribute their fair share? Can this imbalance in past financial contributions be rectified as part of the property division awarded in the divorce proceedings, or must it be pursued as an entirely separate claim? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this important practical question in a decision on November 14, 1978 (Showa 53 (O) No. 706).

The Facts: Separation, Sole Support by the Wife, and a Claim for Reimbursement

The case involved a wife, X, and her husband, Y. They had married in 1962 and had two children. The marriage deteriorated, reportedly due to Y's misrepresentation of his educational background and other instances of dishonest behavior, leading X to become disillusioned. In July 1969, X separated from Y, taking their two children with her.

During the ensuing period of separation, which lasted several years, X single-handedly bore all the living expenses for herself and the children, as well as their educational costs. These expenses amounted to approximately 10 million yen. Y, her husband, contributed nothing towards these costs during this time.

X eventually filed a lawsuit seeking a divorce from Y. In addition to the divorce itself and seeking designation as the custodial parent of their two children, X also requested a property division award of 6 million yen and solatium (damages for emotional distress) of 10 million yen from Y.

The first instance court granted the divorce and awarded custody to X. It ordered Y to pay X 6 million yen as property division and 2 million yen as solatium. On appeal, the High Court upheld the divorce and custody arrangement but increased the financial awards. It ordered Y to pay X 10 million yen for property division and 3 million yen for solatium. In its reasoning for increasing the property division amount, the High Court explicitly stated that it had taken into account the past unpaid marital expenses. It calculated that Y's share of the living and educational expenses that X had solely covered during their separation amounted to 4 million yen. The High Court acknowledged that marital expense sharing is typically a matter determined by the Family Court through specialized non-contentious proceedings known as shinpan (審判, akin to an umpire's decision). However, it concluded that it was appropriate to consider these past unpaid marital expenses as one of the relevant circumstances when determining the amount of property division in the context of the divorce litigation.

Y appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court. His primary argument was that the High Court had erred by including the past marital expense contributions within the property division award. He contended that marital expense sharing was a matter falling under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Family Court to be decided via shinpan procedures, and it was therefore illegal for the High Court, in a litigation procedure for divorce, to effectively determine and incorporate this amount into its property division judgment.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Past Marital Expenses Can Be Considered in Property Division

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's approach.

The Core Principle:

The Court articulated its key finding as follows: "In divorce litigation, when the court determines the amount and method of property division, it should consider all circumstances of both parties, as is clear from the provisions of Article 771 and Article 768, paragraph 3 of the Civil Code." It then directly addressed the issue at hand: "The manner in which past marital expenses were shared during the continuation of the marriage is nothing other than one of these circumstances."

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded: "[I]t is appropriate to construe that the court can determine the amount and method of property division including payments for the settlement of marital expenses that one party has unduly borne." Since the High Court's judgment was in line with this interpretation, it was deemed justifiable.

The Legal Wrinkle: Navigating Different Procedural Tracks

The Supreme Court's decision was significant because it provided a practical solution to a potential procedural impasse. Under Japanese law:

- Property Division (財産分与 - Zaisan Bunyo): Upon divorce, this can be settled by agreement, or if disputed, by a Family Court shinpan. Importantly, if a divorce lawsuit is filed, a claim for property division can be made as an ancillary (attached) claim within that same lawsuit and decided by the court hearing the divorce (under the Code of Procedure in Actions Relating to Personal Status, Article 32, paragraph 1). [cite: 1] This is what X did in this case.

- Marital Expense Sharing (婚姻費用分担 - Kon'in Hiyō Buntan): This, too, is a matter for the Family Court to decide by shinpan if the parties cannot agree (under the Family Case Procedure Act, it's a Type B, Class 2 matter). [cite: 1] However, unlike property division, there was no explicit statutory provision at the time allowing a claim for marital expenses (especially past, unpaid ones) to be made as an ancillary claim directly within the divorce litigation itself. [cite: 1]

Furthermore, at the time this judgment was rendered (1978), divorce litigation fell under the jurisdiction of District Courts, while marital expense shinpan (and property division shinpan, if not ancillary to a divorce suit) were under the jurisdiction of Family Courts. [cite: 1] Thus, Y's argument that the High Court (hearing an appeal from a District Court divorce judgment) was improperly adjudicating a matter reserved for Family Court shinpan procedures had considerable formal procedural weight. [cite: 1] (It's worth noting that under current Japanese law, both divorce litigation and most related family matters, including marital expense shinpan, are now handled by the Family Court, so the specific issue of different courts having jurisdiction is less pronounced, though the distinction between litigation and shinpan as procedural types remains). [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court had also previously established in a 1968 ruling (Showa 43.9.20) that claims for past unpaid marital expenses must be pursued through Family Court shinpan procedures, not through ordinary litigation. [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court's Pragmatic Solution: Consideration as "All Circumstances"

Given these procedural distinctions, the Supreme Court in this 1978 case adopted a pragmatic approach. It did not explicitly state that a divorce court could directly adjudicate a standalone claim for past marital expenses as if it were a shinpan. Instead, it held that the fact that one spouse had disproportionately shouldered past marital expenses, and the extent of this imbalance, constituted one of the "all circumstances" (一切の事情 - issai no jijō) that a court is mandated by Civil Code Article 768, paragraph 3 to consider when determining an equitable property division. [cite: 1]

By framing it this way, the Court allowed the financial reckoning for past unpaid marital support to be effectively integrated into the property division award made within the divorce lawsuit itself. This facilitated a more comprehensive and efficient one-time resolution of the couple's intertwined financial affairs upon divorce. [cite: 1]

Rationale and Compatibility: Purpose and Procedure

While the purposes and standard procedures for property division and marital expense claims differ, the Supreme Court's approach found a way to harmonize their resolution in practice.

- Shared Element of Financial Reckoning: Property division inherently involves a liquidation of the couple's financial relationship and assets accumulated during the marriage. [cite: 1] Viewing the settlement of past, unpaid marital expenses as an element of this overall financial clean-slate process makes their combined consideration within property division conceptually plausible. [cite: 1]

- Nature of Ancillary Property Division Claims: Even when property division is decided as an ancillary claim within divorce litigation, it often retains some characteristics of a non-contentious (hishō) proceeding. For instance, courts exercise broad discretion in determining the division, and the resulting orders may not have the same rigid res judicata effect as typical civil judgments. [cite: 1] Moreover, divorce litigation itself, as a form of personal status litigation, incorporates procedural modifications (e.g., greater scope for judicial investigation, limitations on public access in some instances) that distinguish it from ordinary civil lawsuits. [cite: 1] These features perhaps make the inclusion of considerations normally handled by shinpan (like past marital expenses) more procedurally tenable within this specific litigation context. [cite: 1]

Academic commentators have generally supported the Supreme Court's ruling for its practical benefit of enabling a single, comprehensive resolution of related financial issues and for bringing uniformity to court practice, even if the direct legal path wasn't immediately obvious from the statutes. [cite: 1]

Implications and Unanswered Questions: The Scope of "All Circumstances"

The 1978 Supreme Court decision was lauded for its pragmatism in allowing for a more holistic financial settlement at the time of divorce. However, it did not explicitly address all related questions, leading to further discussion.

A key unresolved issue is whether a property division judgment that considers "all circumstances" (including, implicitly or explicitly, past marital expenses) thereby always and completely extinguishes any separate or subsequent claim for those past marital expenses. [cite: 1] Three main views have emerged in legal discussion:

- The Inclusive View (包括説 - Hōkatsu-setsu): This view holds that any claim for past marital expenses is automatically absorbed into, and settled by, the property division award at the time of divorce. Consequently, a party cannot bring a separate claim for such expenses later. This promotes finality and a one-time resolution. [cite: 1] The two-year statute of limitations for property division claims (from the date of divorce) would then effectively cover these past expense issues as well. [cite: 1] The potential downside is that if past expenses were not adequately considered or compensated in the property division, the aggrieved party would have no further recourse. [cite: 1]

- The Non-Inclusive View (非包括説 - Hi-hōkatsu-setsu): This opposing view maintains that the claim for past marital expenses and the claim for property division are fundamentally distinct and independent. Therefore, a property division judgment does not preclude a party from later filing a separate claim specifically for past unpaid marital expenses. This allows for greater potential fairness if the issue wasn't fully addressed but risks piecemeal litigation. [cite: 1]

- The Limited View (限定説 - Gentei-setsu): This intermediate view suggests that while it's permissible and often desirable for past marital expenses to be considered and settled within the property division, if the awarded property division amount clearly does not account for these past expenses, a separate claim for them might still be possible. Proponents of this view often stress that courts should explicitly state in their property division judgments whether or not past marital expenses have been considered and included. [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court's 1978 ruling is seen as incompatible with the strict Non-Inclusive View but does not definitively choose between the Inclusive View and the Limited View. [cite: 1] The judgment's reliance on the broad language of Civil Code Article 768(3) ("all circumstances") without a detailed theoretical exposition on the precise legal relationship between property division and past marital expense claims leaves this specific point open to ongoing interpretation and debate. [cite: 1] This issue bears similarity to the question of whether a property division award also bars a subsequent claim for solatium (damages for emotional distress), suggesting a need for comparative analysis. [cite: 1]

Conclusion: Pragmatism in Pursuit of Comprehensive Divorce Settlements

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1978 decision was a significant and pragmatic step towards enabling more comprehensive financial resolutions in divorce litigation. By permitting courts to consider the burden of past unpaid marital expenses as one of the "all circumstances" when determining an equitable property division, the Court facilitated a more holistic and efficient settlement process. This approach allows for the practical realities of the spouses' financial history during their marriage, especially during periods of separation, to be factored into the final financial unwinding of their relationship. While the ruling promoted a one-time resolution, the precise extent to which a property division award fully and finally settles all claims for past marital expenses, particularly if not explicitly detailed, remained a subject for continued legal discussion and refinement, emphasizing the ongoing need to balance procedural efficiency with substantive fairness for divorcing parties.