Settling a Dispute, But on What Terms? A 1958 Japanese Supreme Court Case on Mistake in Settlements

Date of Judgment: June 14, 1958

Case Name: Claim for Payment of Goods

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

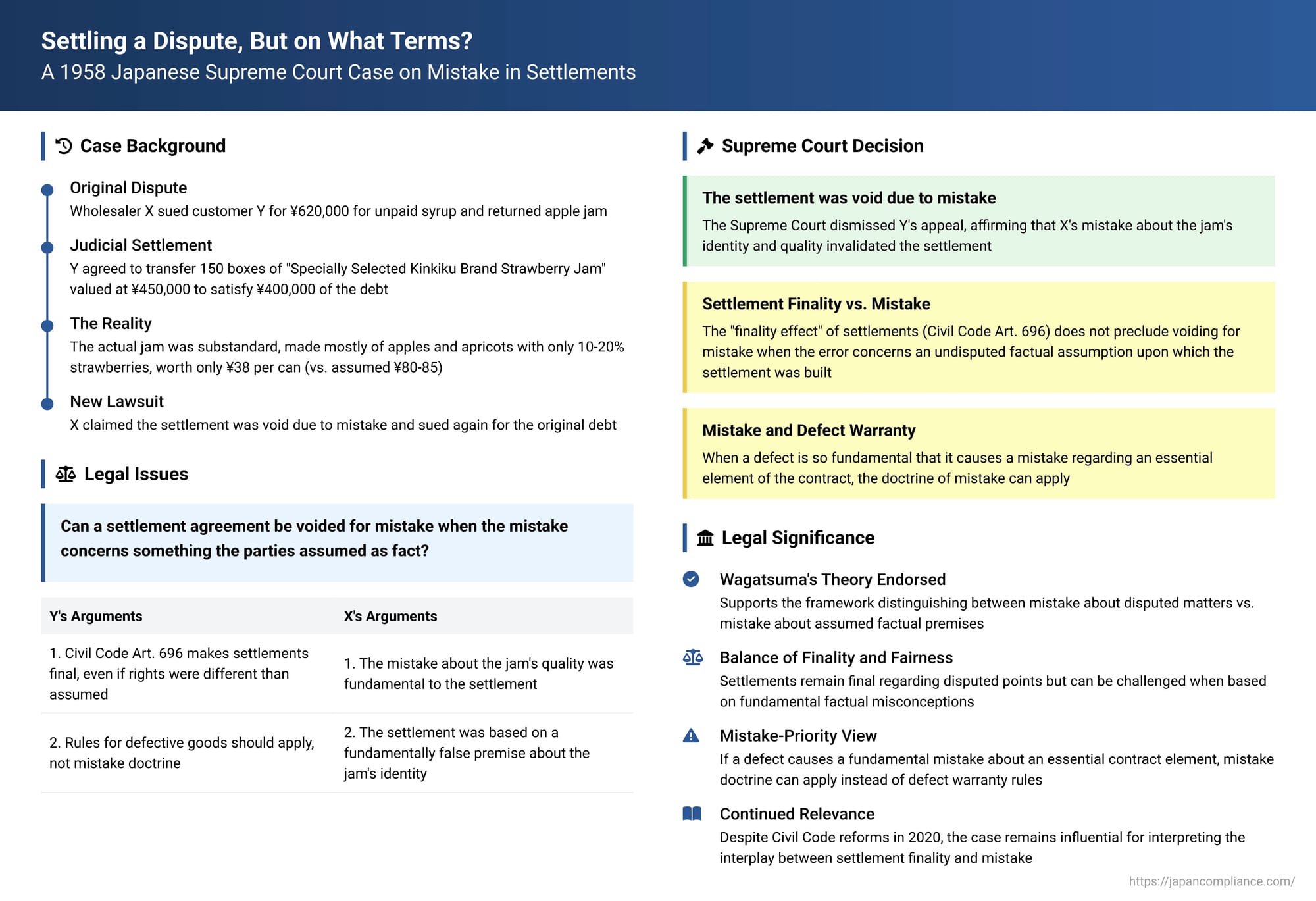

Settlement agreements, known as "wakai" (和解) in Japanese law, are designed to bring disputes to a definitive end. The Civil Code (Article 696) enshrines this principle by stating that once parties settle a dispute through mutual concessions, they generally cannot later challenge the settlement even if it's discovered that the true state of rights was different from what was agreed. This is called the "finality effect" of a settlement. But what happens if the settlement itself is based on a serious misunderstanding or mistake about a crucial fact that the parties took for granted when reaching their accord? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from June 14, 1958, addressed this very tension between the finality of settlements and the legal doctrine of mistake (錯誤 - sakugo).

The Jam Settlement That Soured: The Factual Background

The case originated from a commercial debt dispute that the parties attempted to resolve through a court-mediated settlement:

- The Original Dispute: X, a wholesale company, sued Y, its customer, for approximately ¥620,000. This sum represented the unpaid price of syrup X had sold to Y, as well as a refund X claimed for some apple jam and other goods that Y had sold to X but which X had partly returned.

- The Judicial Settlement: During an oral hearing in court, X and Y reached a settlement with the following terms:

- Y acknowledged its obligation to pay the disputed sum.

- As a partial payment towards this debt (specifically, for ¥400,000 of it), Y agreed to transfer to X ownership of 150 boxes of "Specially Selected Kinkiku Brand Strawberry Jam." This jam had been provisionally seized by X from Y earlier in the dispute. For the purpose of the settlement, these 150 boxes of jam were valued at ¥450,000.

- Since the jam's settlement value (¥450,000) exceeded the portion of the debt it was satisfying (¥400,000), X agreed to pay Y the ¥50,000 difference.

- The jam was to be formally handed over at Y's place of business the following day.

- In exchange for receiving the jam, X agreed to forgive the remaining balance of Y's debt (approximately ¥220,000).

- The Mistaken Premise: Both parties entered into this settlement under the assumption that the jam in question was indeed "Specially Selected Kinkiku Brand Strawberry Jam," a product understood to have a market price of around ¥80 to ¥85 per can. The valuation of ¥450,000 for 150 boxes (equating to roughly ¥62.50 per can after accounting for the number of cans per box typically used in such valuations) was based on this presumed quality and identity.

- The Reality of the Jam: However, the jam that had actually been seized and was the subject of this payment-in-kind was far from the high-quality product assumed. It was, in fact, a substandard concoction made mostly from apples and apricots, with only a small fraction (10-20%) of strawberries. It could not legitimately be sold or recognized as "Kinkiku Brand Strawberry Jam" and its actual market value as a mixed jam was only about ¥38 per can – significantly less than the value assumed in the settlement.

- Claim of Mistake: Upon realizing the true nature of the jam, X asserted that the entire settlement agreement was void due to a fundamental mistake regarding the identity and quality of this key item of consideration. X then re-initiated its claim for the original debt.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance court and the High Court agreed with X, finding the settlement void due to mistake and upholding X's original claim for the debt. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing primarily that:

- The finality effect of a settlement (Civil Code Art. 696) should prevent X from raising a claim of mistake (under former Civil Code Art. 95, which at the time declared acts based on certain mistakes to be void).

- In contracts involving a payment-in-kind (an onerous contract), the specific rules for warranty against defects (瑕疵担保責任 - kashi tanpo sekinin) should take precedence over the general rules of mistake.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, on June 14, 1958, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming that the settlement was indeed void due to X's mistake concerning the jam.

Reconciling Settlement Finality (Article 696) with Mistake (Former Article 95)

The Court addressed Y's primary argument concerning the finality of settlements:

- It acknowledged that the purpose of the original lawsuit (which led to the settlement) was to determine whether Y was liable for the ~¥620,000 debt. The settlement was reached through mutual concessions by X and Y to end that specific dispute.

- However, the Court found that the agreement to use the seized jam as a payment-in-kind was premised (前提 - zentei) on the factual assumption that this jam was the genuine, marketable "Specially Selected Kinkiku Brand Strawberry Jam." The valuation used in the settlement was based entirely on this premise.

- Since the actual jam was a grossly inferior product, the Court concluded that there had been a mistake in a "vital part" (重要な部分 - jūyō na bubun) of the declaration of intent made by X's legal representative when agreeing to the settlement terms.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the High Court had not erred in applying the provisions of (the then-existing) Civil Code Article 95 to find the settlement void. The "finality effect" stipulated in Civil Code Article 696 (preventing settled matters from being re-litigated) does not preclude a party from asserting that the settlement is void due to a mistake concerning a matter that was an undisputed factual assumption or foundation upon which the settlement was built, rather than being one ofthe actual points of contention that the parties mutually agreed to resolve.

Relationship between Mistake and Warranty Against Defects

Regarding Y's second argument (that defect warranty rules should prevail):

- The Supreme Court, citing an earlier Daishin-in (former Supreme Court) precedent from 1921, affirmed the High Court's approach.

- The High Court had effectively found that because the "Kinkiku Brand Strawberry Jam" (the subject of the payment-in-kind) had such significant defects (was not what it was purported to be), this led to a mistake in an essential element of the contract (the settlement agreement).

- In such cases, where a defect in the subject matter gives rise to a fundamental mistake about an essential element of the contract, the party affected can rely on the doctrine of mistake. The specific rules for warranty against defects do not prevent or exclude the application of the mistake doctrine.

The "Wakai-Sakugo" Doctrine: Dissecting the Interplay

This 1958 Supreme Court judgment is a leading case illustrating how Japanese law navigates the interaction between the intended finality of settlement agreements (wakai) and the general contract law principle of mistake (sakugo).

Professor Wagatsuma's Established Framework

Much of the legal understanding in this area has been shaped by a highly influential 1938 academic paper by Professor Sakae Wagatsuma. He categorized mistakes in the context of settlements as follows:

- Type ① Mistake: A mistake concerning the very matter that was in dispute and resolved by the parties' mutual concessions. For example, if parties dispute the amount of a debt, settle on a figure of ¥X, and later, new evidence unequivocally shows the correct figure was ¥Y. In such cases, the finality effect of the settlement (Article 696) prevails, and the settlement cannot typically be undone due to this "mistake." The very purpose of the settlement was to put an end to uncertainty about this disputed point.

- Type ② Mistake: A mistake concerning a matter that was an undisputed "premise or foundation" (前提ないし基礎 - zentei naishi kiso) for the resolution of the disputed issues. This premise was not itself a subject of dispute or concession but was taken for granted by both parties. For example, parties dispute the amount of a debt and settle, but it is later discovered that the debt itself never legally existed in the first place (a fact neither party doubted or disputed during settlement).

- Type ③ Mistake: A mistake concerning matters that fall outside of Types ① and ②. The jam's quality in the 1958 Supreme Court case is generally categorized by legal commentators as fitting this type. The existence and amount of the debt was the Type ① disputed matter. The specific high quality and identity of the "Kinkiku Brand Strawberry Jam" was an assumed attribute of the goods used for the payment-in-kind component of the settlement, not a point of contention that the settlement itself aimed to resolve through mutual concessions.

Professor Wagatsuma's analysis concluded that while Type ① mistakes are generally covered by the settlement's finality, settlements affected by Type ② or Type ③ mistakes can potentially be challenged under the rules of mistake, because the mistaken matters were not what the parties had agreed to stop arguing about. The 1958 Supreme Court judgment aligns with this framework, as it allowed the mistake regarding the jam's quality (an assumed attribute, not the core dispute) to void the settlement.

Application Challenges and Current Law

While this framework is widely accepted, distinguishing between a "matter in dispute" (Type ①) and an "undisputed premise" (Type ②) can sometimes be challenging in practice. Some Supreme Court decisions, particularly those involving settlements reached in court or through formal mediation processes where state organs are involved, have shown a reluctance to allow subsequent challenges based on mistake, perhaps reflecting a judicial inclination to uphold the finality of such formally concluded resolutions. However, legal commentators note that these cases might also have involved situations where a mistake claim would have failed anyway (e.g., the mistake was merely one of motive, or the mistaken party was grossly negligent).

The Japanese Civil Code underwent significant revisions concerning contract law, which came into effect in 2020. The rules on mistake (now Article 95) were amended (e.g., mistake now generally leads to a right of avoidance/cancellation rather than automatic voidness). During the deliberations for these reforms, proposals to codify Professor Wagatsuma's framework for the interplay between settlement and mistake were considered. Ultimately, no specific new statutory provision was enacted on this point, meaning the issue remains largely one of judicial interpretation based on the principles established by cases like this 1958 judgment.

Mistake versus Contract Non-Conformity (Formerly Defect Warranty)

The 1958 Supreme Court decision also touched upon the relationship between mistake and warranty against defects (which, under the post-2020 Civil Code, is now part of the broader concept of "liability for non-conformity of contract" - 契約不適合責任, keiyaku futekigō sekinin).

The Court in 1958 effectively endorsed a "mistake-priority view": if a defect in an item is so fundamental that it causes a mistake regarding an essential element of the contract involving that item, the mistaken party can rely on the doctrine of mistake to (at that time) have the contract declared void. This was somewhat at odds with a strong academic view that favored the precedence of specific defect warranty rules (with their typically shorter time limits for claims) over the more general rules of mistake.

Under the current Civil Code, since mistake now generally gives a right to avoid or cancel the contract (which itself has statutory time limits for exercise), and the rules for non-conformity also provide a range of remedies (repair, price reduction, damages, termination), it is now more widely understood that an aggrieved party may often have a choice of which legal avenue to pursue if the facts support both a claim for mistake and a claim for non-conformity. The old tensions about mistake claims circumventing the stricter time limits of defect warranty have been somewhat eased by the reforms.

Conclusion

The 1958 Supreme Court decision remains a significant precedent in Japanese contract law. It carves out an important sphere for the application of the doctrine of mistake even in the context of settlement agreements, which are otherwise intended to be final. The ruling establishes that if a settlement is predicated on a shared, fundamental, but erroneous assumption of fact – where that fact was not itself the subject of the dispute being compromised – the settlement may be vulnerable to a challenge for mistake. This carefully balances the important public policy of upholding settlements with the equally important principle of ensuring that contractual consent is not vitiated by serious and elemental misapprehensions.