Setting the Record Straight? Japan's Supreme Court on Correcting Third-Party Medical Claim Forms Held by Government

Judgment Date: March 10, 2006

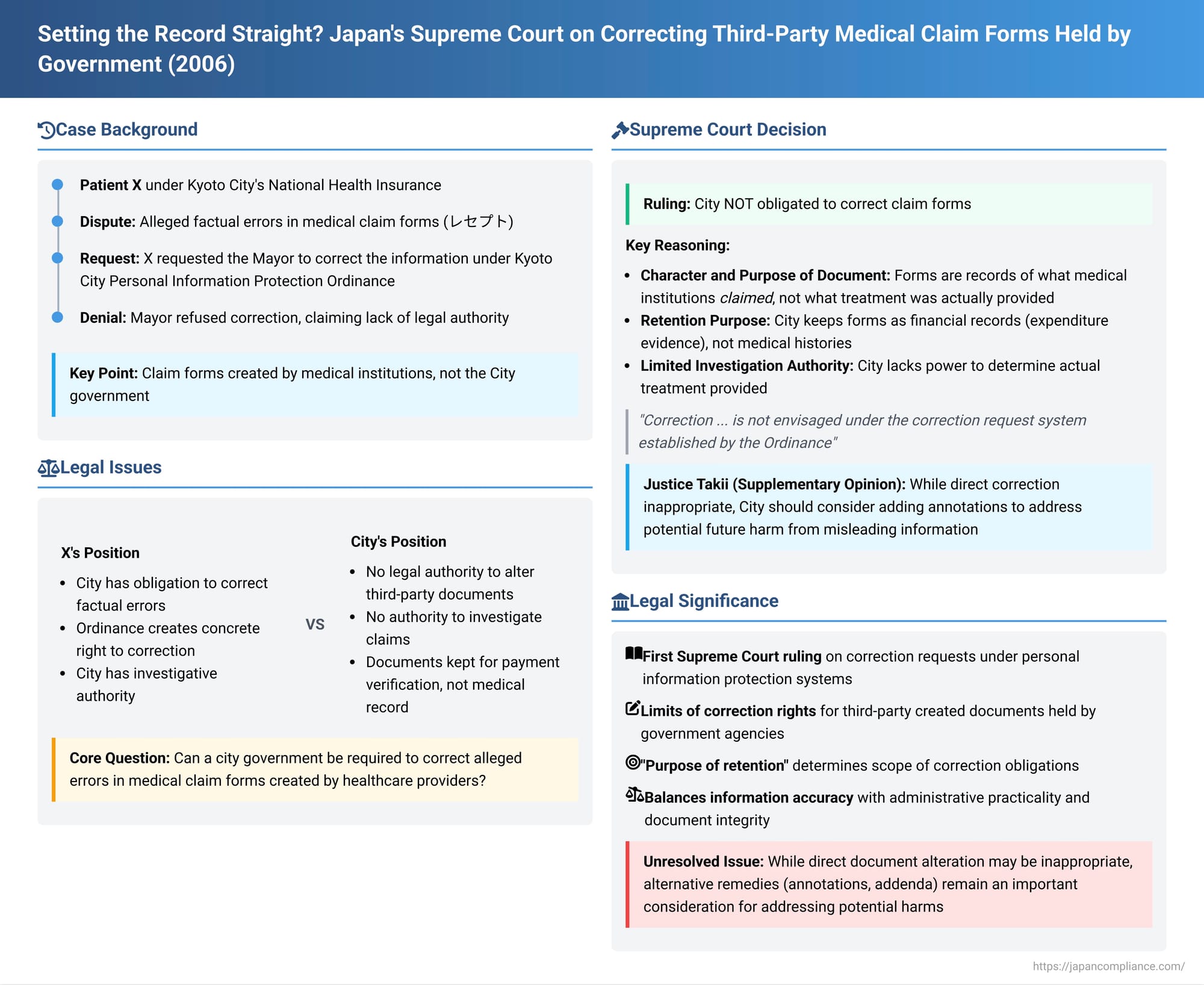

The right of individuals to access and correct their personal information held by government agencies is a fundamental component of data protection and informational self-determination. However, the scope and limits of this right to correction can become complex, particularly when the information in question was originally created by a third party and is held by a government agency for specific administrative or evidentiary purposes. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from March 10, 2006 (Heisei 13 (Gyo-Hi) No. 289), delved into precisely such a scenario, examining whether a city government was obligated to correct alleged factual errors in National Health Insurance medical claim forms submitted by healthcare providers. [cite: 1] This case highlights the intricate balance between an individual's interest in the accuracy of their data and the defined roles and limitations of public bodies that manage such information.

The Patient's Plea: A Dispute Over Medical Billing Records

The plaintiff, X, was an insured person under the National Health Insurance plan administered by Kyoto City. [cite: 1] X alleged that there were factual errors in the National Health Insurance medical claim forms (kokumin kenkō hoken shinryō hōshū meisaisho, commonly known as "rezepto" or claim forms) related to medical treatment X had received. [cite: 1] These claim forms detailed the services provided and the fees charged by medical institutions. [cite: 1] Exercising rights under the Kyoto City Personal Information Protection Ordinance (hereinafter "the Ordinance"), X requested the Mayor of Kyoto City, Y (the defendant, representing the implementing agency), to correct these alleged inaccuracies. [cite: 1]

Mayor Y, however, issued a decision not to correct the information in the claim forms. [cite: 1] The City's rationale was twofold: firstly, that the City lacked the legal authority to alter these claim forms, and secondly, that it consequently lacked the authority to conduct the necessary investigation to verify X's correction request. [cite: 1]

The procedural background of these claim forms is crucial to understanding the dispute. In Kyoto City, as per the National Health Insurance Act, the administrative tasks related to the review of medical fee claims submitted by insurance medical institutions and the subsequent payment of these fees were outsourced to the Kyoto Prefecture National Health Insurance Federation ("the Federation"). [cite: 1] The claim forms at issue were originally prepared by the various medical institutions where X had received treatment. [cite: 1] These institutions submitted the forms to the Federation, which then reviewed them before forwarding them to Kyoto City. [cite: 1] After Kyoto City disbursed the medical fees to the institutions (via the Federation), the City retained these claim forms as part of its records. [cite: 1] X had, prior to making the correction request, lawfully obtained disclosure of these claim forms under the provisions of the same Ordinance. [cite: 1]

Lower Courts: Conflicting Views on City's Authority

X challenged the Mayor's non-correction decision in court. The Kyoto District Court, as the court of first instance, ruled in favor of X. [cite: 1] It found that, based on an interpretation of the National Health Insurance Act, Kyoto City, as the insurer, possessed the authority to review the claim forms, and from this premise, also possessed the authority to correct them. [cite: 1] Therefore, the City's refusal to correct, based on a purported lack of authority, was deemed illegal. [cite: 1]

The Osaka High Court, on appeal, upheld the District Court's decision to rule in X's favor. [cite: 1] However, it added a significant layer to the reasoning. The High Court opined that the Kyoto City Personal Information Protection Ordinance itself established a concrete right for individuals to request corrections. [cite: 1] It asserted that under this Ordinance, the implementing agency (the City) could and should take "corrective measures" when factual errors in personal information were found, irrespective of whether it had the authority to directly alter the original document itself. [cite: 1] Furthermore, the High Court stated that the City should exercise its investigative powers granted by the Ordinance to determine the validity of a correction request, and that this duty was independent of any investigative or corrective powers (or lack thereof) the City might have under the National Health Insurance Act. [cite: 1] Both lower courts, therefore, essentially agreed that the City had an obligation to investigate and act upon X's correction request. [cite: 1] Dissatisfied with the High Court's ruling, Mayor Y sought and was granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court. [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 10, 2006): Defining the Limits of Correction

The Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, overturned the decisions of the lower courts and ultimately dismissed X's claim for correction. [cite: 1] The Court's judgment focused on the specific nature of the claim forms and the intended scope of the correction system under the Kyoto City Ordinance.

Focus on the Ordinance and Limited Investigative Powers

The Supreme Court primarily analyzed the City's obligations concerning correction requests through the lens of the Kyoto City Personal Information Protection Ordinance. [cite: 1] It acknowledged that the Ordinance mandates the implementing agency, upon receiving a correction request, to conduct necessary investigations and then decide whether to make the correction. [cite: 1] However, the Court noted that the Ordinance "does not provide any special provisions granting the implementing agency the necessary investigative authority for this purpose, and it is clear that there are inherent limits to the external investigative authority possessed by the implementing agency". [cite: 1]

The "Character" and "Purpose" of the Document: The Core Rationale

The crux of the Supreme Court's reasoning lay in its assessment of the intrinsic nature and administrative purpose of the medical claim forms:

- Origin and Primary Function: The claim forms are prepared by the insurance medical institutions themselves. [cite: 1] Their purpose is to claim payment for medical services rendered under the National Health Insurance system, detailing the treatments the institutions assert they provided. [cite: 1] These are then submitted to the Federation for review. [cite: 1]

- City's Role and Retention Purpose: Kyoto City receives these forms after the Federation's review and uses them as the basis for paying the claimed medical fees to the institutions (via the Federation). [cite: 1] Subsequently, the City retains these claim forms primarily as "evidentiary documents for its income and expenditure" related to these medical fee payments. [cite: 1]

- Unsuitability of Alteration by the City: Given this context, the Supreme Court stated that for the implementing agency (the City) to correct the information recorded by a medical institution in a claim form, based on an allegation that the described treatment differs from what was actually provided by that institution, would be "unsuitable for the character of the claim forms as documents that clarify the content of medical care fees claimed by the medical institution". [cite: 1] In essence, altering the form would misrepresent what the medical institution had originally claimed and what the City had paid.

Information Not Managed to Reflect "Actual Treatment" by the City

The Supreme Court further elaborated on the purpose for which the City held X's medical information as recorded in the claim forms. It referred to Article 8, paragraph 1 of the Ordinance, which implies that personal information collected by the City should be managed and utilized within the scope necessary to achieve the objectives of the specific administrative affairs for which it was collected. [cite: 1]

Applying this, the Court found that, considering the City's stated purpose for retaining the claim forms (i.e., as financial records of payments made), the information about X's treatment recorded therein was not, at the time of X's correction request, being managed by the City for the primary purpose of directly clarifying the actual medical treatment X had received. [cite: 1] Therefore, the Court found it "difficult to consider" this information, as held and used by the City, as "directly pertaining to X's rights and interests" in a way that would trigger an obligation for the City to investigate and alter the content to reflect X's version of the actual treatment. [cite: 1]

Correction "Not Envisaged" by the Ordinance's System

Considering these points—the limited external investigative powers of the City under the Ordinance and the specific character and retention purpose of the claim forms—the Supreme Court concluded that the Ordinance "does not require the City to conduct necessary investigations regarding the actual medical treatment X received and then correct the information concerning X's medical treatment in the claim forms, even in such cases". [cite: 1]

Ultimately, the Court held that correcting the descriptions of X's medical treatment in these particular claim forms is "not envisaged under the correction request system established by the Ordinance". [cite: 1] Thus, Mayor Y's decision not to make the correction was not illegal. [cite: 1]

Justice Takii's Supplementary Opinion: Acknowledging the "Strong Implication"

Justice Shigeo Takii, in a supplementary opinion, concurred with the majority's outcome but offered additional perspectives. He emphasized that the "direct meaning of the information in the claim forms is the fact that the medical institution claimed medical fees on the grounds that it performed the medical acts as described". [cite: 1] In this narrow sense, the claim forms are not "incorrect" because they accurately reflect what was claimed by the provider and subsequently paid by the insurer (the City). [cite: 1] The forms themselves do not primarily serve to prove the actual existence or precise details of the medical treatment received by the patient. [cite: 1]

However, Justice Takii acknowledged that the information recorded on these claim forms "gives rise to a strong inference that the individual named on the claim form received the medical treatment described therein". [cite: 1] In this respect, if the actual treatment differed, the information on the form could indeed become "incorrect information," which was X's central concern. [cite: 1]

While agreeing that the Ordinance, given the nature of these claim forms, does not provide a basis for the City to directly alter (add to or delete from) the document itself to reflect the patient's account of the actual treatment, Justice Takii suggested an alternative approach. [cite: 1] He pointed to the City's general responsibility under Article 3, paragraph 1 of the Ordinance to take necessary measures for the protection of personal information. [cite: 1] He proposed that if the City holds information that strongly implies incorrect facts about an individual, and if there is a possibility that this information might be used in the future, the City should endeavor to mitigate any potential harm. [cite: 1] Therefore, when a correction request like X's is made, highlighting such a discrepancy, "it is desirable for operational measures to be taken, such as adding an annotation to the document where the retained personal information is recorded, so that if the information is used thereafter, this matter will be understood". [cite: 1]

Unpacking the Legal Reasoning (Commentary Insights)

This Supreme Court decision was the first by the nation's highest court on a correction request under a personal information protection system, making its reasoning particularly noteworthy. [cite: 1]

- Correction of Third-Party Documents: A key issue was whether an agency has an obligation to correct information in documents it did not create (in this case, the claim forms were created by medical institutions). [cite: 1] Some personal information protection ordinances explicitly exempt an agency from correction duties if it lacks the authority to correct the document (e.g., Mie Prefecture's ordinance). [cite: 1] The Kyoto Ordinance, at the time, lacked such an explicit provision. [cite: 1] The Supreme Court's approach, using the "purpose of retention" and the "character of the document" as grounds to limit the City's correction authority, demonstrated a way to define such limits even without an explicit statutory exclusion. [cite: 1] However, legal commentary suggests this reasoning is highly specific to the nature of these medical claim forms and does not establish a general theory for the correction of all third-party documents. [cite: 1] The ruling did not comprehensively clarify the general relationship between an agency's powers under specific governing statutes (like the National Health Insurance Act) and its correction powers under personal information protection ordinances; this broader question was left for future cases. [cite: 1] The Court's reference to limited investigative powers was seen by commentators as a less decisive factor in its conclusion compared to its arguments about the document's inherent character and purpose. [cite: 1]

- Relevance of "Purpose of Use": Many personal information protection laws, including Japan's national Act (Article 92), stipulate that correction should be made "within the scope necessary to achieve the purpose of use" of the personal information. [cite: 1] The Kyoto Ordinance was later amended to include a similar provision. [cite: 1] The Supreme Court's reasoning in this case, particularly its reference to Article 8, paragraph 1 of the Ordinance (concerning the scope of use), aligns with this principle, suggesting that the exercise of correction authority should be consistent with the intended use of the information by the holding agency. [cite: 1]

- The Meaning of "Fact" Subject to Correction: The Ordinance allows for the correction of "errors of fact". [cite: 1] While "fact" clearly excludes subjective evaluations or judgments, its precise scope can be debated. [cite: 1] The Supreme Court, in this case, effectively defined the "fact" recorded in the claim forms as "the content of medical treatment the medical institution states it provided" or "the content of fees for medical benefits the medical institution claimed". [cite: 1] This interpretation means that the "fact" as recorded on the document was viewed through the filter of the document's specific character and purpose for the City, thereby distinguishing it from the "fact" of "X's actual medical treatment". [cite: 1] The "fact" pertinent to the claim form, from the City's perspective as payer and record-keeper of claims, was what the medical institution asserted, not necessarily what the patient experienced. [cite: 1]

- Alternative Rectification Methods: The Supreme Court found it "difficult to consider" the information in the claim forms, as held by the City for payment verification, as "directly pertaining to X's rights and interests" in a manner that would mandate correction of its content regarding actual treatment. [cite: 1] However, legal commentators, and indeed Justice Takii's supplementary opinion, acknowledge that an individual has a legitimate interest in preventing future adverse consequences that might arise from records containing information that, even if technically accurate from one perspective (what was claimed), is misleading as to another (what was actually received). [cite: 1] Thus, even if a decision not to directly alter the document is deemed lawful, alternative methods of "rectification," such as adding an annotation or note to the file, as suggested by Justice Takii, are considered desirable. [cite: 1] Some argue that such annotation could even be interpreted as a form of correction that individuals have a right to request. [cite: 1] This line of thinking approaches the position taken by the Osaka High Court, which distinguished between "correction of the document itself" and "corrective measures" that could be taken under the Ordinance. [cite: 1]

Implications for Individuals and Record-Keeping Agencies

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision provides important clarification on the limitations of an individual's right to demand direct alteration of third-party documents held by government agencies, especially when these documents serve a primary administrative purpose other than directly reflecting the "ground truth" of an individual's personal circumstances or experiences.

- It underscores that the "purpose of retention" by the holding agency is a key factor in defining the scope of its obligations to correct information.

- While limiting direct alteration in such contexts, the judgment, particularly through Justice Takii's supplementary opinion, opens the door for discussion and implementation of alternative remedies or operational practices, such as annotation, to address individuals' legitimate concerns about potentially misleading information contained in official records.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's ruling in the Kyoto City medical claim form case offers a nuanced interpretation of an individual's right to seek correction of personal information held by public authorities. By focusing on the specific character of the document in question—a claim form created by a third party (the medical institution) and held by the City primarily for financial and evidentiary purposes related to payment processing—the Court concluded that direct alteration of its content to reflect the patient's differing account of actual treatment was "not envisaged" by the city's personal information protection ordinance. While this limits the scope of direct correction for such third-party transactional documents, the judgment, along with the insightful supplementary opinion, also highlights the ongoing responsibility of public agencies to manage personal information with care and to consider practical measures to mitigate potential harm from records that, while accurate for their primary purpose, might be misleading in other contexts. This decision contributes to the evolving understanding of how data protection principles are applied to the diverse range of information held by government bodies.