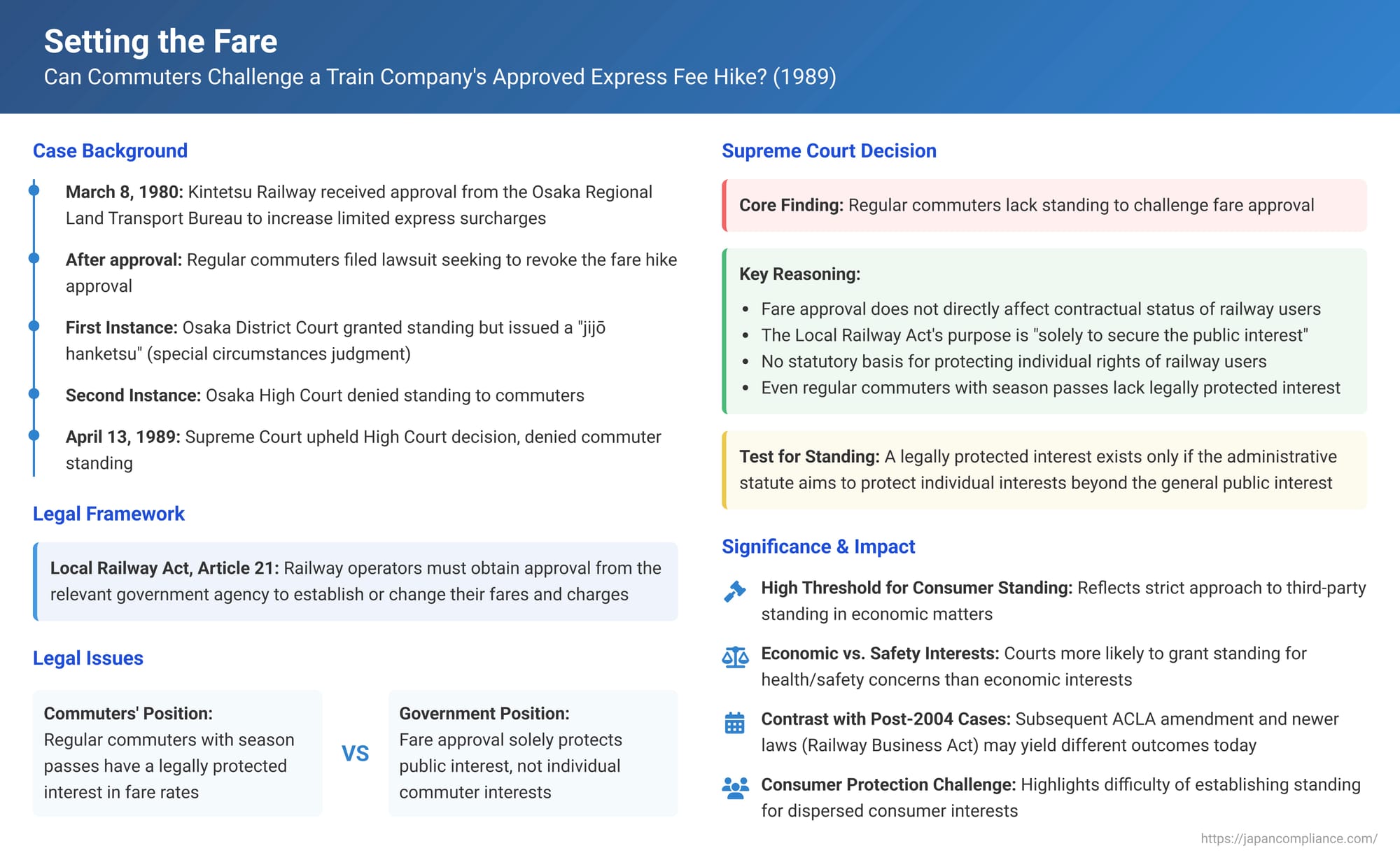

Setting the Fare: Can Commuters Challenge a Train Company's Approved Express Fee Hike?

Judgment Date: April 13, 1989, Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Public transportation fares and fees are a matter of daily concern for millions. In Japan, private railway companies often require government approval to set or change fares, including surcharges for services like limited express trains. But if regular commuters believe an approved fare hike is illegal or unreasonable, do they have the legal standing to challenge that government approval in court? A 1989 Supreme Court decision involving the Kintetsu Railway addressed this question, ultimately finding that such commuters lacked the "legal interest" necessary to sue.

The Local Railway Act and Fare Approvals

At the time of this case, the Local Railway Act (地方鉄道法 - Chihō Tetsudō Hō, since repealed and replaced by the Railway Business Act) governed the operation of many private railways in Japan. Article 21 of this Act required railway operators to obtain the approval (認可 - ninka) of the relevant supervisory government agency (in this case, the Director of the Osaka Regional Land Transport Bureau, acting for the Minister of Transport) to establish or change their fares and charges, including special express train fees. This approval process was intended to ensure that fares were set in a manner consistent with the public interest.

The Kintetsu Express Fare Hike: Facts of the Case

Kinki Nippon Railway Co., Ltd. (commonly known as Kintetsu), a major private railway operator, applied for and, on March 8, 1980, received approval from Y (the Director of the Osaka Regional Land Transport Bureau) to revise (increase) its limited express train surcharges.

X et al. (the plaintiffs) were regular commuters who used Kintetsu lines, purchased commuter passes, and frequently rode the limited express trains affected by the fare hike. Believing the approval of the fare increase was illegal, they filed an administrative lawsuit seeking the revocation of Y's approval disposition. They also filed a separate claim for damages against the State, which is not the primary focus here.

The lower courts differed on the crucial issue of plaintiff standing:

- The Osaka District Court (First Instance) found that X et al. did have standing. It distinguished them from individuals who might only use the railway sporadically, noting their status as daily commuters with season passes. While ultimately ruling that the approval itself was illegal, the court issued a "judgment on special circumstances" (事情判決 - jijō hanketsu), meaning it did not revoke the approval due to the potential public disruption, but acknowledged its illegality.

- The Osaka High Court (Second Instance), on appeal, reversed this. It ruled that X et al. lacked the necessary "legal interest" to challenge the approval and dismissed their lawsuit as inadmissible. X et al. then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (April 13, 1989): No Standing for Commuters

The Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, dismissed the appeal by X et al., thereby upholding the High Court's decision that they lacked plaintiff standing.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Approval's Direct Effect: The Supreme Court stated that an approval disposition for a fare change under Article 21 of the Local Railway Act does not, in itself, directly affect the contractual status of the railway users. This holds true regardless of how frequently or regularly they use the service.

- Purpose of the Local Railway Act: The Court interpreted the purpose of Article 21 as being "solely to secure the public interest". It was not intended to protect the "individual rights or interests of the users of the said local railway".

- No Other Basis for Individual Protection: The Court found no other basis in the Local Railway Act to suggest that the approval power was constrained by a purpose of protecting the individual rights or interests of railway users.

- Conclusion on Standing: Therefore, even though X et al. were residents along Kintetsu lines, purchased commuter passes, and regularly used the limited express trains, they could not be considered persons "whose rights or interests are infringed or are inevitably threatened with infringement by the approval disposition for the revision (change) of the said limited express fares". Consequently, they lacked the plaintiff standing necessary to seek the revocation of the approval, and their lawsuit was deemed inadmissible.

Analyzing "Legally Protected Interest": The Court's Framework

The Supreme Court's decision hinged on its interpretation of "legal interest" (法律上の利益 - hōritsujō no rieki) required for plaintiff standing under Article 9, Paragraph 1 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA).

The Established Test

The Court implicitly followed its established test for standing: a person has a "legal interest" if "the said disposition infringes upon their rights or legally protected interests, or there is an inevitable risk of such infringement". For a third party (someone other than the direct addressee of the disposition, which in this case was the railway company), their interest is deemed "legally protected" if "the administrative statute that provides the basis for the said disposition is construed as including an aim to protect, as individual interests of each person to whom they belong, the concrete interests of an unspecified number of persons, beyond merely absorbing and dissolving them into the general public interest".

Application in This Case

- No Direct Infringement of "Rights": The Court first determined that the fare approval did not directly infringe any established "rights" of the commuters in a way that would automatically grant standing. The approval was directed at the railway company, and the commuters' obligation to pay the new fare arose from their individual contracts of carriage with the company, not directly from the government's approval itself. The first instance court had pointed out that "the approval for a fare revision is not the fare revision itself, and furthermore, the obligation to pay fares only arises if one actually uses the said railway". This line of reasoning suggests that there is no immediate, unavoidable impact on a "right" solely from the act of approval.

- No "Legally Protected Individual Interest" under the Statute: The Supreme Court then found that the Local Railway Act's provision for fare approval (Article 21) was intended solely to protect the general "public interest" (公益 - kōeki). It was not designed to protect the individual economic interests of railway users. The Court saw no language or purpose in the statute that would elevate the commuters' interest in lower fares to the status of an "individually protected interest" that the Act specifically aimed to safeguard when the government reviewed fare applications.

The "Individual Interest Protection" Requirement

This decision reflects a common pattern in Supreme Court standing jurisprudence: for third parties to have standing, the empowering statute must be interpreted as intending to protect their interests as specific, individual interests, rather than merely as part of the general public good. If an interest is seen as being "absorbed and dissolved into the general public interest," it is often considered a "reflective interest" (反射的利益 - hanshateki rieki), which is generally insufficient for standing.

A tendency in Supreme Court cases:

- Where infringements of life or health are alleged, courts are often more inclined to find that the relevant statutes protect individual interests, thus granting standing (e.g., the Niigata Airport noise case, the Monju nuclear reactor case).

- Where the alleged harm is primarily economic or involves other types of interests (like in this Kintetsu fare case, or cases involving historical site preservation), the Court has been more reluctant to find that the statutes protect individual interests sufficient for standing.

Impact of the 2004 ACLA Revision

It is important to note that this judgment was rendered before the 2004 revision of the ACLA. This revision introduced Article 9, Paragraph 2, which provides factors for courts to consider when determining if an interest is "legally protected." These factors include the purpose of the empowering statute and related laws, and the content, nature, manner, and extent of the harm if the disposition were illegal. This amendment was generally aimed at providing clearer guidance and potentially broadening access to courts for third parties.

The Broader Context of Consumer Interests

The Kintetsu Express Fare case is significant as a Supreme Court ruling on the standing of consumers (in this case, railway users) to challenge administrative approvals that affect prices. Consumer interests are diverse, ranging from significant economic impacts (as potentially in this case for daily commuters) to more diffuse interests (as in cases involving product labeling where the individual harm might be small but widely shared).

Establishing standing for consumer interests can be challenging, particularly under the "individual interest protection" requirement. It's not always easy to distinguish a specific consumer's interest from the general interest of all consumers, especially if the harm is primarily a small economic one.

Conclusion

The 1989 Supreme Court decision in the Kintetsu Express Fare case denied standing to regular commuters seeking to challenge the government's approval of a railway fare increase. The Court found that the Local Railway Act's fare approval provision was intended to protect the general public interest, not the individual economic interests of specific users, even frequent ones. This meant the commuters lacked the "legally protected interest" required to bring a revocation suit.

The ruling reflects a traditionally strict approach by the Supreme Court to third-party standing, emphasizing the need for a clear statutory basis for recognizing individual protected interests. However, the subsequent 2004 revision of the Administrative Case Litigation Act, which introduced more detailed guidance for interpreting "legal interest," and later lower court decisions under different statutory schemes (like the Railway Business Act with its explicit user protection clause), suggest an evolving landscape. While this 1989 decision remains an important precedent for cases under similar older statutes, the broader trend may be towards a more nuanced consideration of the practical impact of administrative actions on individuals and a potentially more flexible approach to standing, especially where newer laws explicitly mention the protection of user or consumer interests.