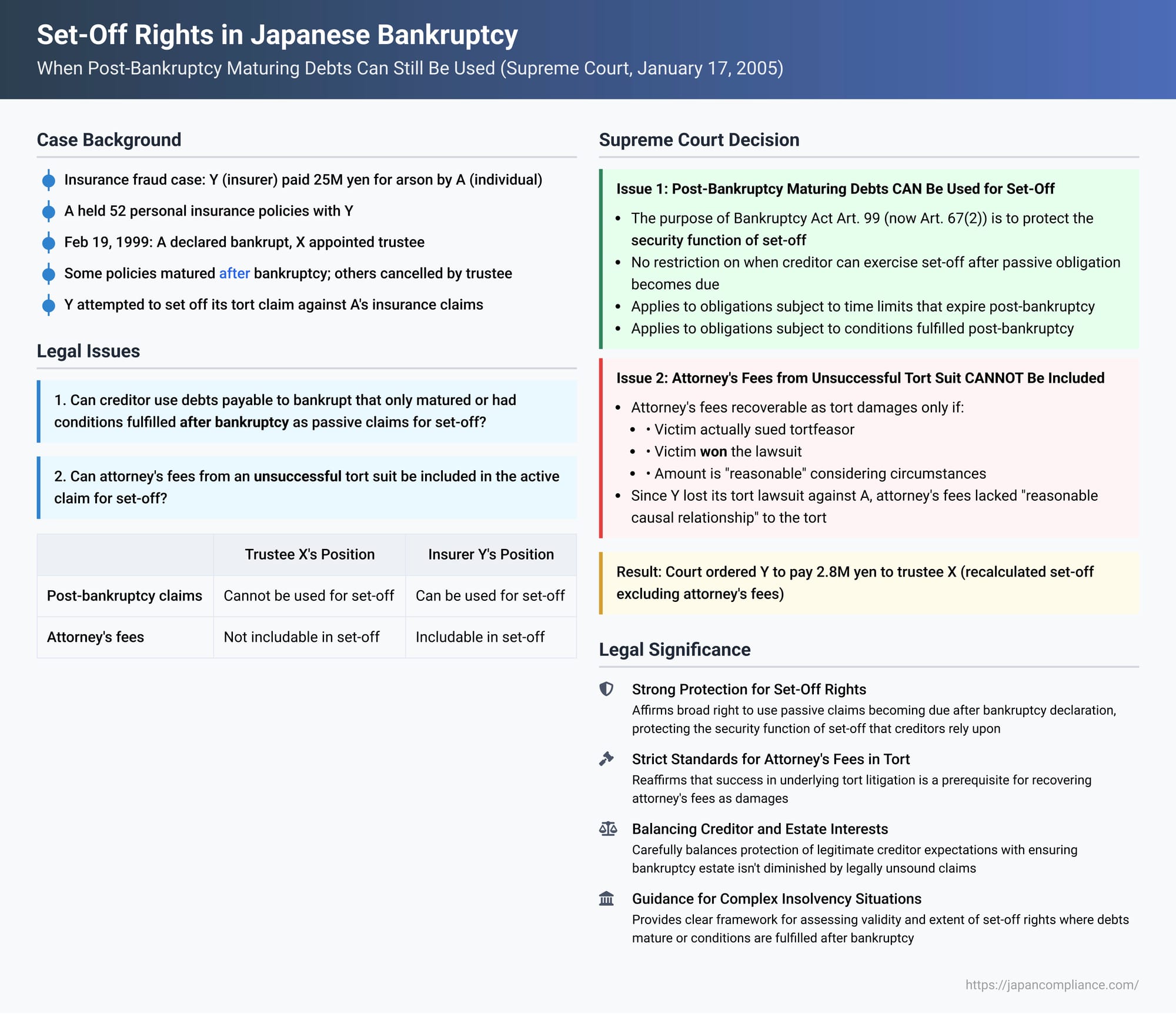

Set-Off Rights in Japanese Bankruptcy: When Post-Bankruptcy Maturing Debts Can Still Be Used

The right of set-off (相殺 - sōsai) is a powerful tool for creditors in Japanese bankruptcy proceedings. If a creditor also happens to owe a debt to the bankrupt entity, they can often "set off" these mutual obligations, effectively allowing the creditor to receive preferential payment on their own claim up to the amount of the debt they owed. However, complexities arise when the creditor's debt to the bankrupt (which would be the passive side of the set-off) was not yet due, or was subject to a condition, at the precise moment bankruptcy proceedings commenced, only becoming fully payable after bankruptcy started. Can a creditor still exercise their right of set-off in such a situation? A Supreme Court of Japan decision from January 17, 2005, provided significant clarification on this issue, while also addressing the allowability of including attorney's fees from a related tort lawsuit as part of the active claim used for set-off.

Factual Background: Insurance Fraud, Bankruptcy, and Competing Claims

The case involved Y, an insurance company, and A, an individual who was the representative director of B Co.

- Y had issued a store comprehensive insurance policy to B Co. for a building owned by B Co.

- A subsequently committed arson on this building in an attempt to fraudulently claim the insurance money. Y, initially unaware of the arson, investigated the fire damage (incurring investigation costs of approximately 0.35 million yen) and paid out insurance proceeds of approximately 25.14 million yen to B Co.

- After the arson came to light, Y initiated a lawsuit against A personally, seeking damages for the tort of insurance fraud. Y's claim included the amount of the insurance payout, the investigation costs, and an additional 2.55 million yen for attorney's fees incurred in pursuing this tort litigation against A.

- Separately, Y had also issued numerous (52) personal insurance policies (such as installment savings type accident insurance contracts) directly to A.

- On February 19, 1999, A was declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act, and X was appointed as A's bankruptcy trustee. At this point, trustee X succeeded to A's position as defendant in the ongoing tort lawsuit brought by Y.

- Status of A's Insurance Policies with Y at Bankruptcy Declaration:

- Some of A's personal insurance policies with Y (Nos. 1-21) had already matured before A's bankruptcy declaration. The maturity benefits due to A from these policies totaled approximately 11.33 million yen.

- Other policies (Nos. 22-52) had not yet matured at the time of bankruptcy.

- A subset of these (Nos. 22-24, savings type) reached their maturity dates after A's bankruptcy declaration (in March 1999).

- The remaining policies (Nos. 25-52, mostly savings type with two being term policies) were cancelled by trustee X after A's bankruptcy declaration (on April 2, 1999). This cancellation triggered A's right to claim their cash surrender values.

- The combined total of these post-bankruptcy maturity benefits and cash surrender values (for policies No. 22-52) amounted to approximately 22.29 million yen. This sum is referred to as "the subject return monies."

- Y's Attempted Set-Off: On May 15, 1999, Y (the insurance company) declared its intention to set off its total tort damages claim against A against A's total claims for all insurance return monies (both pre- and post-bankruptcy triggered). Y calculated its total damages claim against A at approximately 30.86 million yen (comprising the insurance payout, investigation costs, the disputed attorney fees, and pre-bankruptcy delay damages). A's total claims against Y for insurance return monies from all 52 policies amounted to approximately 33.62 million yen. After performing the set-off, Y paid the net balance of approximately 2.76 million yen to trustee X on May 19, 1999.

- It was not disputed by the parties that Y's tort damages claim could be validly set off against the maturity benefits from policies Nos. 1-21 (totaling approx. 11.33M yen), as these obligations of Y to A were already unconditionally due before A's bankruptcy.

- Trustee X's Lawsuit: Trustee X filed the present lawsuit against Y, demanding payment of the remaining portion of "the subject return monies" – specifically, the approximately 19.52 million yen that Y had retained by setting it off against its tort claim, which X argued was impermissible for obligations that became due only post-bankruptcy.

The first instance court, in the context of the separate (but consolidated for trial) tort lawsuit, had dismissed Y's damages claim against A (succeeded by X), and this dismissal had become final. In X's current lawsuit against Y for the return monies, the High Court ultimately found Y's set-off to be valid even against the insurance proceeds that became due post-bankruptcy, and therefore dismissed X's entire claim. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issues

Two main legal questions were before the Supreme Court:

- Set-Off with Passive Claims Maturing or Having Conditions Fulfilled Post-Bankruptcy: Can a bankruptcy creditor (Y) use a debt they owed to the bankrupt (A's claims for insurance maturity benefits or cash surrender values) as the passive claim for a set-off if that debt only became unconditionally due (e.g., the policy matured, or the policy was cancelled by the trustee thereby triggering the surrender value) after the bankruptcy proceedings for A had commenced? This was governed by the latter part of Article 99 of the old Bankruptcy Act (similar in substance to Article 67, paragraph 2, of the current Bankruptcy Act).

- Inclusion of Attorney's Fees in Active Claim for Set-Off: Could the creditor (Y) legitimately include the attorney's fees incurred in its separate (and ultimately unsuccessful) tort lawsuit against the bankrupt (A) as part of its active damages claim for the purpose of calculating the set-off?

The Supreme Court's Ruling – Part I: Set-Off with Post-Commencement Maturing/Conditional Passive Claims IS Permissible

On the primary issue, the Supreme Court held that Y (the insurance company) could indeed set off its tort damages claim against A against the insurance return monies that became due to A (and thus A's bankruptcy estate) even if those monies became due (through policy maturity) or payable (through cancellation by the trustee triggering cash surrender value) only after A's bankruptcy proceedings had begun.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose of Bankruptcy Act's Set-Off Provision (Old Art. 99, latter part; Current Art. 67(2)): The relevant statutory provision explicitly stated that if a bankruptcy creditor's debt to the bankrupt (which the creditor would use as the passive claim in a set-off) was subject to a time limit or a condition precedent at the time of the bankruptcy declaration, this circumstance does not prevent the creditor from effecting a set-off. The Supreme Court explained that the legislative purpose of this rule is to protect the creditor's legitimate expectation in the inherent security function of set-off (相殺の担保的機能 - sōsai no tanpoteki kinō). When parties have mutual debts, they often rely, implicitly or explicitly, on the possibility of setting these debts off as a form of mutual security. The Bankruptcy Act aims to preserve this reliance.

- No Restriction on Timing of Set-Off Exercise: The statute itself placed no restriction on when the creditor could exercise this right of set-off once their passive obligation to the bankrupt became unconditionally due. Japanese bankruptcy law generally does not limit the timing for exercising valid set-off rights that existed (even if contingently) at the commencement of proceedings.

- Application to Debts Subject to Time Limits and Conditions Precedent:

- Therefore, if the creditor's debt to the bankrupt was subject to a time limit (e.g., payable on a future maturity date) at the time of bankruptcy, the creditor can validly set off their claim against this debt not only if they choose to waive the benefit of that time limit (i.e., treat the debt as immediately due for set-off purposes), but also if the time limit naturally expires after the bankruptcy declaration, making the debt unconditionally due then (absent any special circumstances that would bar set-off).

- Similarly, if the creditor's debt to the bankrupt was subject to a condition precedent at the time of bankruptcy, set-off is permissible not only if the creditor might waive the benefit of the condition (though this is less common for conditions precedent owed to the bankrupt), but also if the condition is actually fulfilled after the bankruptcy declaration, thereby making the debt unconditionally due.

- Conclusion for this Case: In A's bankruptcy, Y's obligations to pay maturity benefits on certain policies (Nos. 22-24) were subject to time limits (the future maturity dates) which occurred post-bankruptcy. Y's obligations to pay cash surrender values on other policies (Nos. 25-52) were subject to a condition precedent (cancellation of the policies), which was fulfilled post-bankruptcy by trustee X's actions. The Supreme Court found no "special circumstances" that would bar set-off in this instance. Therefore, Y was entitled to use these matured/fulfilled obligations (A's claims for "the subject return monies") as the passive claims for setting off its active tort damages claim against A. The High Court's decision on this primary point was thus affirmed as correct.

The Supreme Court's Ruling – Part II: Attorney's Fees from Unsuccessful Tort Suit NOT Includable in Active Claim for Set-Off

On the secondary issue, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred. It ruled that Y (the insurance company) could not include the 2.55 million yen in attorney's fees, which it had incurred in pursuing its separate (and ultimately unsuccessful) tort lawsuit against A for insurance fraud, as part of its active damages claim for the purpose of calculating the set-off.

The Court's reasoning on this point was:

- Established Rule for Recoverable Attorney's Fees as Tort Damages: The Supreme Court reiterated its long-standing principle regarding the recovery of attorney's fees as a component of tort damages. Such fees are recoverable from the tortfeasor only if:

- The victim actually instituted a lawsuit against the tortfeasor to claim other items of damage arising from that same tort.

- The victim won that lawsuit against the tortfeasor.

- Even if these conditions are met, only an amount of attorney's fees deemed "reasonable" by the court—taking into account factors like the difficulty of the case, the amount claimed, the amount awarded, and other relevant circumstances—can be claimed as damages having a "reasonable causal relationship" (相当因果関係 - sōtō inga kankei, or proximate cause) to the original tort.

- Application to Y's Attorney's Fees: In this case, the record showed that the first instance court, in the consolidated proceedings, had actually dismissed Y's separate tort lawsuit against A (as succeeded by trustee X), and that part of the judgment (the dismissal of the tort claim) had become final and unappealable.

- Conclusion: Since Y had not prevailed in its tort lawsuit against A, the attorney's fees Y incurred in pursuing that unsuccessful litigation could not be recognized as damages having the requisite reasonable causal relationship to A's original tortious act of insurance fraud.

Recalculation by the Supreme Court and Final Outcome

Having disallowed the 2.55 million yen in attorney's fees from Y's active claim for set-off, the Supreme Court recalculated the legitimate amount of damages Y could use. This valid active claim consisted of the insurance payout Y had made to B Co., Y's investigation costs, and pre-bankruptcy delay damages on these amounts.

The Court then found that Y's valid set-off, using this recalculated active claim, extinguished only a portion of trustee X's claim for "the subject return monies" (the insurance proceeds that became payable to A's estate post-bankruptcy). There was a remaining balance that Y had improperly retained.

Consequently, the Supreme Court modified the High Court's judgment. It ordered Y (the insurance company) to pay trustee X the sum of 2,805,000 yen (representing the improperly withheld portion of the insurance return monies after a valid set-off of the reduced damages claim) plus delay damages on this amount from May 19, 1999 (the date Y had paid the initial, smaller balance to X after its broader, now partially invalidated, set-off).

Significance and Implications

This 2005 Supreme Court decision carries several important implications for bankruptcy law and practice in Japan:

- Confirmation of Broad Set-Off Rights for Post-Commencement Maturing/Conditional Passive Claims: The judgment strongly affirms a creditor's right to effect a set-off in bankruptcy under Article 99, latter part, of the old Bankruptcy Act (and by direct analogy, Article 67, paragraph 2, of the current Act). This right applies even when the creditor's own obligation to the bankrupt (which serves as the passive claim for set-off) only becomes unconditionally due—either through the expiry of a time limit or the fulfillment of a condition precedent—after the commencement of the bankruptcy proceedings. This robustly protects the "security function of set-off" that creditors often rely upon.

- Reaffirmation of Strict Conditions for Recovering Attorney's Fees in Tort: The case serves as a clear reminder of the stringent conditions under Japanese law for a tort victim to recover their attorney's fees as part of their damages claim. A fundamental prerequisite is success in the underlying tort litigation against the tortfeasor. This high standard applies even when the tort damages claim is being utilized as an active claim for the purpose of set-off within a bankruptcy context.

- Balancing Creditor Expectations and Estate Interests: The decision carefully navigates the balance between protecting a creditor's legitimate expectation in the security afforded by mutual indebtedness (the right of set-off) and ensuring that the bankruptcy estate is not improperly diminished by claims that lack a solid legal foundation (such as attorney's fees from an unsuccessful lawsuit).

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's January 17, 2005, judgment provides significant clarity on two distinct but related aspects of set-off in Japanese bankruptcy. Firstly, it confirms the broad scope of a creditor's ability to use their obligations to the bankrupt as passive claims for set-off, even if those obligations only crystallize after bankruptcy proceedings have begun, thereby upholding the important security function of set-off. Secondly, it reiterates the strict legal standard for recovering attorney's fees as part of a tort damages claim, requiring success in the tort litigation itself, a standard that applies equally when such damages are asserted as an active claim for set-off in bankruptcy. This ruling offers valuable guidance for both creditors and bankruptcy trustees in assessing the validity and extent of set-off rights in complex insolvency situations.