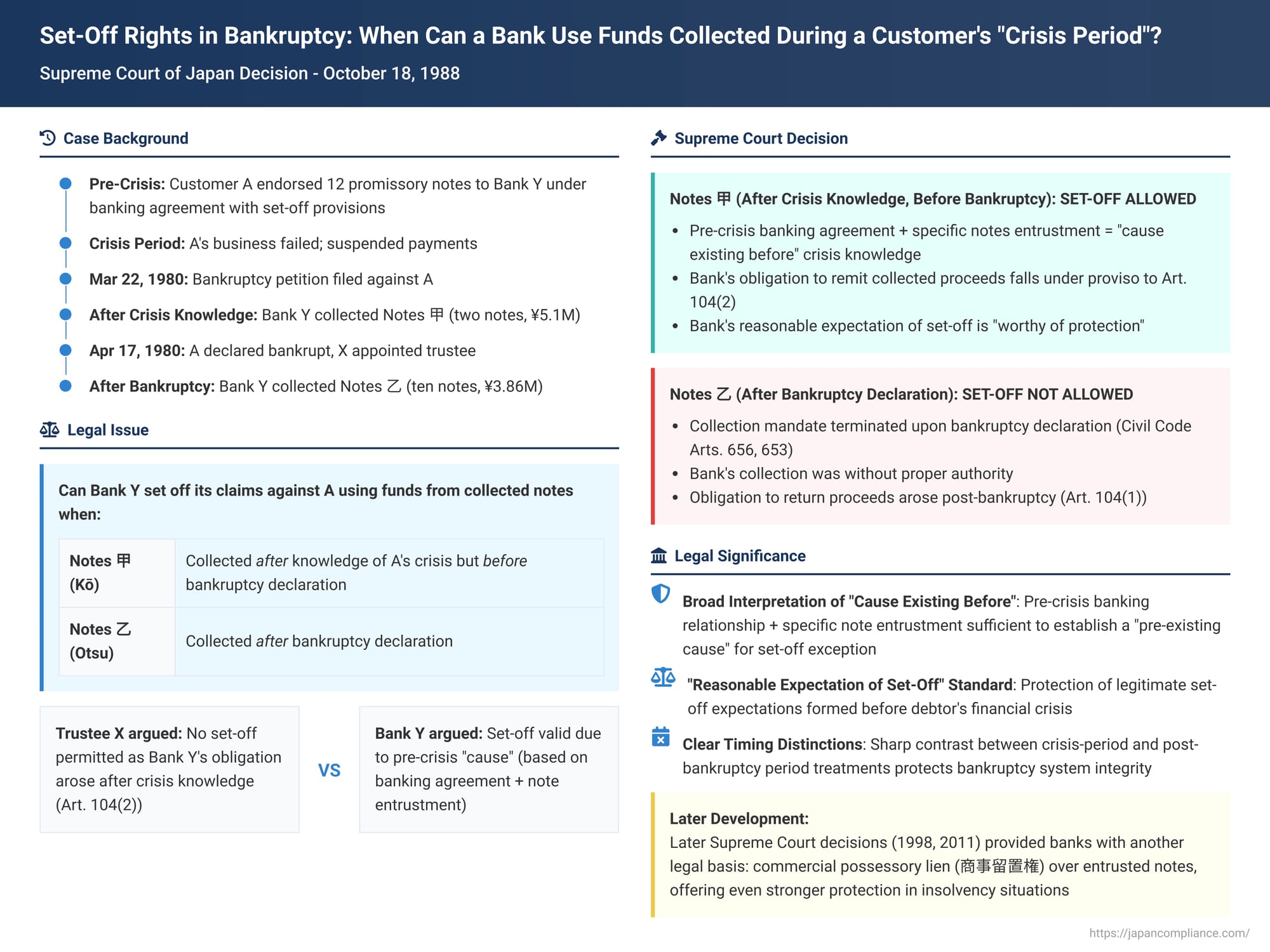

Set-Off Rights in Bankruptcy: When Can a Bank Use Funds Collected During a Customer's "Crisis Period"? A 1988 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

The right of set-off (相殺 - sōsai) is a significant tool for creditors in Japanese bankruptcy proceedings. It allows a party who is both a creditor and a debtor to the bankrupt to net out their mutual obligations, often resulting in the creditor effectively receiving a preferential recovery on their claim up to the amount of the debt they owed to the bankrupt's estate. However, this powerful right is not unlimited. Bankruptcy law imposes restrictions to prevent unfairness to other creditors, particularly concerning debts incurred by the creditor to the bankrupt when the creditor already knew of the bankrupt's financial distress. A Supreme Court of Japan decision from October 18, 1988, provided crucial interpretation on an exception to these restrictions, specifically in the context of a bank collecting promissory notes entrusted by a customer after becoming aware of that customer's financial crisis but before their formal bankruptcy.

Factual Background: Entrusted Notes, Financial Crisis, Collection, and a Set-Off Dispute

The case involved A, an individual engaged in the auto parts sales business, who had a long-standing banking relationship with Y Bank (a credit union). This relationship was governed by a comprehensive banking transaction agreement (信用金庫取引約定書 - shinyō kinko torihiki yakujōsho). This agreement contained several standard clauses, including:

- Clause 4, paragraph 4: Stipulated that if A failed to perform any obligations to Y Bank, Y Bank was authorized to collect or dispose of any of A's movables, promissory notes, or other securities in Y Bank's possession. Y Bank could then apply the net proceeds from such collection or disposal to A's outstanding debts in any order Y Bank deemed appropriate, not necessarily following statutory priorities.

- Clause 6, paragraph 1: Provided that if A suspended payments or if a bankruptcy petition was filed against A, Y Bank could demand immediate repurchase by A of any promissory notes that Y Bank had previously discounted for A.

In the course of their business, A had endorsed and delivered 12 promissory notes to Y Bank for collection. Subsequently, A's financial situation deteriorated significantly due to the dishonor of notes from A's own customers. A closed the business and entered a state of "suspension of payments" (支払の停止 - shiharai no teishi). On March 22, 1980, A's creditors filed a bankruptcy petition against A. Formal bankruptcy proceedings under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act commenced with a declaration of bankruptcy on April 17, 1980, and X was appointed as A's bankruptcy trustee.

The timing of Y Bank's collection of the 12 entrusted notes became critical:

- Notes 甲 (Two notes, "Notes Kō"): Y Bank collected these notes, totaling approximately 5.1 million yen, after A had suspended payments and after the bankruptcy petition had been filed against A (and Y Bank was aware of these events), but before A was formally declared bankrupt.

- Notes 乙 (Ten notes, "Notes Otsu"): Y Bank collected these notes, totaling approximately 3.86 million yen, after A had been formally declared bankrupt.

Trustee X subsequently demanded that Y Bank return the collected proceeds of Notes 甲. For Notes 乙, X demanded either the return of the notes themselves (if uncollected) or their value as unjust enrichment (if already collected). Y Bank, however, sought to set off the collected proceeds from both sets of notes against its own claims against A. These claims primarily consisted of A's obligation to repurchase previously discounted promissory notes, an obligation that had become immediately due when the bankruptcy petition was filed against A, as per Clause 6(1) of their banking agreement.

The Osaka District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (on appeal) both ruled substantially in favor of trustee X, denying Y Bank's right to set off for both Notes 甲 and Notes 乙.

- Regarding Notes 甲 (collected post-knowledge of crisis but pre-declaration), the High Court held that Y Bank's obligation to remit the collected funds to A arose after Y Bank knew of A's financial crisis. It reasoned that the "cause existing before" such knowledge, which would permit set-off under the proviso to Article 104, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act, must be a specific and direct cause of the debt obligation. The High Court found that the general bill collection mandate stemming from the overall banking transaction agreement was not a sufficiently direct cause. Thus, set-off was prohibited by the main part of Article 104, item 2.

- Regarding Notes 乙 (collected post-bankruptcy declaration), the High Court held that the collection mandate given by A to Y Bank had terminated upon A's formal bankruptcy declaration (pursuant to agency principles in the Civil Code, Articles 656 and 653). Therefore, Y Bank collected these notes without proper authority. Its obligation to return these proceeds to the trustee was characterized as an unjust enrichment arising after the bankruptcy declaration. Under Article 104, item 1, of the old Bankruptcy Act (similar to Article 71, paragraph 1, item 1 of the current Act), a creditor generally cannot set off against a debt they incurred to the bankruptcy estate after the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings.

Y Bank appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issue: What Constitutes a "Cause Existing Before" Knowledge of Crisis for Set-Off Purposes?

The primary legal issue for the Supreme Court concerned Notes 甲: Was Y Bank's obligation to hand over the collected proceeds of these notes (which arose when Y Bank collected them after learning of A's financial crisis) incurred due to a "cause existing before" Y Bank had knowledge of A's crisis? If so, the proviso to Article 104, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act would permit set-off, despite Y Bank's later knowledge. If not, the main part of that provision would prohibit set-off.

The old Bankruptcy Act Article 104, item 2, stipulated that a bankruptcy creditor could not set off their claim if they incurred a debt towards the bankrupt after knowing that the bankrupt had suspended payments or that a bankruptcy petition had been filed. However, a crucial proviso stated that this prohibition did not apply if the debt was incurred based on a "cause existing before" (前ニ生ジタル原因 - mae ni shōjitaru gen'in) the creditor acquired such knowledge. The interpretation of this "cause existing before" was central.

A secondary issue, for Notes 乙, was the permissibility of set-off against an obligation arising from collection of notes after the formal bankruptcy declaration.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Banking Agreement + Pre-Crisis Note Entrustment = "Cause Existing Before"

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision. It allowed Y Bank's set-off concerning Notes 甲 but affirmed the denial of set-off for Notes 乙.

Set-Off for Notes 甲 (Collected Post-Knowledge of Crisis, Pre-Declaration) IS ALLOWED:

The Supreme Court held that Y Bank's obligation to remit the proceeds of Notes 甲 was indeed based on a "cause existing before" it knew of A's financial crisis. Its reasoning was:

- General Principle of Set-Off's Security Function: The Court began by acknowledging that when parties have mutual debts, the possibility of set-off provides an inherent security function. Both parties often rely on this expectation when continuing their business relationship. While unrestricted set-off after bankruptcy commencement could undermine the bankruptcy system's goal of equal treatment for creditors, Article 104, item 2, (main part) addressed this by prohibiting set-off when the creditor's debt to the bankrupt was incurred after the creditor knew of the debtor's crisis.

- Purpose of the "Cause Existing Before" Proviso: The proviso to Article 104, item 2, which allows set-off if the debt was based on a "cause existing before" such knowledge, is intended to protect the security function of set-off for transactions that are rooted in the pre-crisis period and to safeguard transactional security where a creditor had a legitimate expectation of set-off.

- Application to the Facts: The Supreme Court found that when a bankruptcy creditor (like Y Bank), before becoming aware of the debtor's (A's) suspension of payments or the filing of a bankruptcy petition against them:

- Had entered into a comprehensive banking transaction agreement with the debtor, which included clauses permitting the creditor to collect or dispose of the debtor's promissory notes in their possession and apply the proceeds to the debtor's obligations in case of default; AND

- Had received specific promissory notes from the debtor under a collection mandate, evidenced by endorsement and delivery;

THEN, even if the creditor actually collects these notes after learning of the debtor's suspension of payments or bankruptcy petition (but before the formal bankruptcy declaration), the creditor's resulting obligation to hand over the collected proceeds to the debtor is deemed to have arisen from a "cause existing before" they acquired knowledge of the crisis.

- Reasonable Expectation of Set-Off: The Court reasoned that in such circumstances, the creditor's expectation that they would be able to set off the proceeds from collecting these entrusted notes against the debtor's liabilities is worthy of protection under the spirit and purpose of the proviso in Article 104, item 2. The High Court had erred in its overly narrow interpretation that the general banking and collection mandate agreement did not constitute a "specific and direct cause." The Supreme Court found that the combination of the pre-existing agreement and the pre-crisis entrustment of the specific notes for collection formed a sufficient pre-existing "cause."

Set-Off for Notes 乙 (Collected Post-Bankruptcy Declaration) IS NOT ALLOWED:

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court regarding Notes 乙.

- The mandate for Y Bank to collect these notes on behalf of A terminated by operation of law upon A's formal bankruptcy declaration (pursuant to Civil Code Articles 656 and 653, which govern the termination of agency upon the principal's bankruptcy).

- Therefore, Y Bank's collection of these notes after A's bankruptcy declaration was without proper authority. Its obligation to return these proceeds to the bankruptcy trustee was consequently an obligation for unjust enrichment that arose after the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings.

- Under Article 104, item 1, of the old Bankruptcy Act (now Article 71, paragraph 1, item (a) of the current Act), a creditor is prohibited from setting off against a debt they incurred to the bankruptcy estate after the bankruptcy proceedings have commenced. Thus, Y Bank could not set off its claims against this post-declaration obligation.

Significance of the "Reasonable Expectation of Set-Off" Criterion

This 1988 Supreme Court judgment is considered a leading case for its interpretation of the "cause existing before" knowledge of crisis exception to the general prohibition of set-off in certain circumstances.

- It established that the "cause" is not limited to the very last act that makes the debt payable but can encompass a foundational pre-crisis contractual relationship (like a comprehensive banking agreement authorizing set-off) coupled with a specific pre-crisis act of entrusting the instruments (like promissory notes) that will later generate the debt owed by the creditor to the bankrupt.

- The concept of a "reasonable expectation of set-off" arising from such pre-existing arrangements became a key factor in the Court's analysis. If a creditor had a legitimate and foreseeable basis for expecting to set off, rooted in agreements and actions taken before they knew of the debtor's dire financial situation, that expectation warrants protection under the Bankruptcy Act's set-off provisions.

Later Developments and the Interplay with Commercial Possessory Liens

It is worth noting, as the provided PDF commentary (for bk65.pdf) points out, that subsequent Supreme Court decisions in 1998 (for bankruptcy, discussed as "BK53") and 2011 (for civil rehabilitation, discussed as "BK54") provided banks with an alternative, and often stronger, legal basis for retaining and applying the proceeds of notes held from customers who later entered insolvency proceedings: the commercial possessory lien (商事留置権 - shōji ryūchiken).

- Those later cases affirmed that a bank's commercial possessory lien over such notes generally survives the customer's bankruptcy or civil rehabilitation (at least concerning the bank's right to retain possession of the notes or their collected proceeds). Based on standard banking agreement clauses allowing for the application of collateral, the bank could then collect the notes and apply the proceeds to its claims.

- This means that, in current practice, a bank finding itself in a situation similar to Y Bank's might first assert its rights based on its commercial possessory lien. The argument for set-off based on the "cause existing before" knowledge of crisis (as established in this 1988 judgment) would still be a relevant, perhaps secondary or alternative, line of reasoning, especially if there were any doubt about the applicability or scope of the commercial possessory lien in a particular factual scenario.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's October 18, 1988, decision significantly clarified the scope of a creditor's right to set-off in bankruptcy when their obligation to the bankrupt (the passive claim for set-off) arises from actions taken after the creditor became aware of the bankrupt's financial crisis. By holding that a pre-existing comprehensive banking agreement combined with the pre-crisis entrustment of specific promissory notes for collection constitutes a "cause existing before" knowledge of the crisis, the Court allowed the bank to set off proceeds collected from those notes even if the actual collection occurred after such knowledge was acquired (but before formal bankruptcy declaration). This ruling emphasized the protection of a creditor's "reasonable expectation of set-off" that is formed based on pre-crisis dealings. However, it also strictly upheld the prohibition against set-off for obligations incurred due to actions (like collecting notes) taken after the formal commencement of bankruptcy proceedings, when the underlying mandate had terminated. While later developments in case law concerning commercial possessory liens have provided additional avenues for banks in similar situations, this 1988 judgment remains a key precedent for interpreting the statutory exceptions to set-off prohibitions in Japanese bankruptcy law.