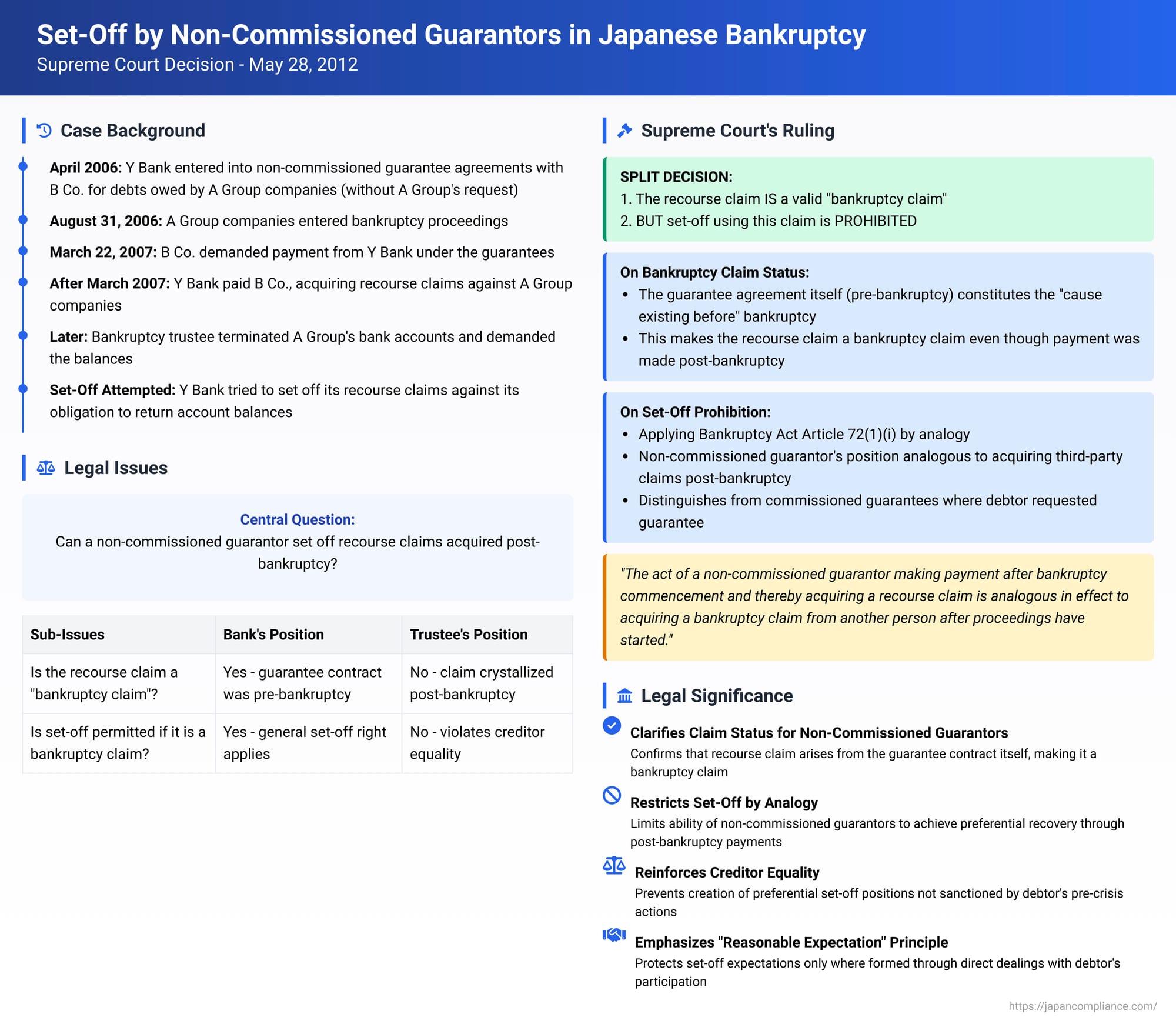

Set-Off by Non-Commissioned Guarantors in Japanese Bankruptcy: A 2012 Supreme Court Clarification

The right of set-off (相殺 - sōsai) is a significant feature of Japanese bankruptcy law, allowing a creditor who also owes a debt to the bankrupt entity to offset these mutual obligations. This often results in the creditor obtaining a more favorable recovery than general unsecured creditors. However, the Bankruptcy Act imposes restrictions on this right to uphold the principle of creditor equality, particularly concerning claims or debts that arise or are acquired under circumstances that might give the setting-off creditor an unfair advantage after the debtor's financial crisis is apparent. A key Supreme Court of Japan decision on May 28, 2012, addressed a nuanced aspect of these restrictions: the ability of a non-commissioned guarantor (a guarantor who provided a guarantee without the principal debtor's request or commission) to set off a recourse claim, which arose from paying the principal debt after the principal debtor's bankruptcy, against a debt the guarantor owed to the bankrupt.

Factual Background: Non-Commissioned Guarantees, Bankruptcy, and Attempted Set-Off

The case involved a group of companies, referred to as A Group, which all had current account agreements (当座勘定契約 - tōza kanjō keiyaku) with Y Bank. On April 28, 2006, Y Bank, without being commissioned or requested by any of the A Group companies, entered into guarantee agreements with B Co., a significant business partner of A Group. Under these non-commissioned guarantee agreements (無委託保証 - mu-itaku hoshō), Y Bank guaranteed the trade payable debts and promissory note obligations that A Group companies owed to B Co., up to specified maximum amounts, for a period of one year.

On August 31, 2006, all A Group companies had bankruptcy proceedings commenced against them by the Osaka District Court. Initially, C was appointed as their bankruptcy trustee (later succeeded by X, the appellant before the Supreme Court).

Subsequently, on March 22, 2007—well after the A Group companies had entered bankruptcy—B Co. (the original creditor) demanded that Y Bank perform its obligations under the non-commissioned guarantee agreements. Y Bank duly made payments to B Co. in fulfillment of these guarantees, thereby satisfying A Group's debts to B Co. ("the subject payments"). As a result of these payments, Y Bank acquired "recourse claims" (求償権 - kyūshōken) against the A Group companies for the amounts it had paid on their behalf.

The bankruptcy trustee (then C) later terminated A Group's current account agreements with Y Bank and initiated a lawsuit demanding that Y Bank pay over the outstanding balances in these accounts to the respective bankruptcy estates. In response to this demand, Y Bank asserted its right to set off. It claimed that the recourse claims it had acquired against A Group (by making "the subject payments" to B Co. under the non-commissioned guarantees) should be set off against its own obligations to return the current account balances belonging to A Group.

Both the Osaka District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (on appeal) upheld Y Bank's right to set off. The bankruptcy trustee (now X) then successfully petitioned the Supreme Court for acceptance of the appeal.

The Legal Issues: Status of the Recourse Claim and Permissibility of Set-Off

The Supreme Court had to address two main legal questions:

- Is a Recourse Claim Acquired by a Non-Commissioned Guarantor from a Post-Bankruptcy Payment a "Bankruptcy Claim"? For Y Bank to even contemplate set-off under the general rules, its recourse claim against A Group needed to qualify as a "bankruptcy claim" (破産債権 - hasan saiken). A bankruptcy claim is generally defined as a monetary claim against the debtor that arose from a "cause existing before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings" (Bankruptcy Act Article 2, paragraph 5). Did Y Bank's recourse claim, which only became a fixed monetary obligation when Y Bank paid B Co. after A Group's bankruptcy, meet this definition because the underlying (non-commissioned) guarantee agreement was made pre-bankruptcy?

- If it is a Bankruptcy Claim, Can it Be Used for Set-Off? Even if the recourse claim is a bankruptcy claim, Article 72, paragraph 1, item (i) of the Bankruptcy Act generally prohibits a person who owes a debt to the bankrupt from setting off against that debt if they acquired a bankruptcy claim of another person after the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings. While Y Bank's recourse claim was its own, not "another person's" in the typical sense of an assignment, the Court had to consider if the circumstances of its acquisition post-commencement by a non-commissioned guarantor warranted a similar restriction by analogy to prevent an outcome contrary to creditor equality.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Recourse Claim is a Bankruptcy Claim, but Set-Off is Prohibited by Analogy

The Supreme Court partially reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case, effectively denying Y Bank's right of set-off under these specific circumstances.

I. Recourse Claim of a Non-Commissioned Guarantor is a Bankruptcy Claim:

- The Court first affirmed that a recourse claim acquired by a non-commissioned guarantor is indeed a "bankruptcy claim" if the guarantee agreement itself was concluded before the principal debtor's bankruptcy proceedings commenced, even if the guarantor makes the payment (and the recourse claim thereby crystallizes) after the commencement of those proceedings.

- The reasoning is that the guarantee agreement itself forms the underlying legal basis or "cause" for the future recourse claim. Since this "cause" (the guarantee contract) existed before the bankruptcy proceedings began, the resulting recourse claim falls within the definition of a bankruptcy claim under Article 2, paragraph 5 of the Bankruptcy Act. The Court stated that this principle applies regardless of whether the guarantee was made with or without the principal debtor's commission.

II. Set-Off Using This Recourse Claim by a Non-Commissioned Guarantor is PROHIBITED by Analogous Application of Bankruptcy Act Article 72, Paragraph 1, Item (i):

This was the crucial part of the judgment.

- General Principle of Set-Off and Its Security Function (Article 67): The Court began by acknowledging the general principle enshrined in Article 67 of the Bankruptcy Act. This article generally permits a bankruptcy creditor who also owed a debt to the bankrupt at the time bankruptcy proceedings commenced to exercise a right of set-off. This right is recognized because set-off serves a "security-like function" (担保的機能 - tanpoteki kinō), allowing a creditor with mutual debts to achieve a degree of preferential recovery. In this respect, the right of set-off is treated similarly to a formal "right of separation" (betsujoken) held by secured creditors.

- Statutory Restrictions on Set-Off (Articles 71 and 72): However, the Court emphasized that this right of set-off is not absolute. Articles 71 and 72 of the Bankruptcy Act impose restrictions on set-off in certain situations where its exercise would undermine the fundamental bankruptcy principle of ensuring fair and equal treatment among creditors. Specifically, Article 72, paragraph 1, item (i) prohibits set-off if a person who owes a debt to the bankrupt (the passive claim) acquired a bankruptcy claim of another person (the active claim) after the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings. This is to prevent parties from strategically buying up claims post-bankruptcy solely to effect a set-off and gain an undue preference.

- Distinguishing Between Commissioned and Non-Commissioned Guarantors for Set-Off Purposes: The Supreme Court then drew a critical distinction:

- Commissioned Guarantor: If a guarantor who was commissioned by the bankrupt debtor makes a payment after bankruptcy commencement and thereby acquires a recourse claim, set-off using this recourse claim against a pre-existing debt owed by the guarantor to the bankrupt is generally permissible. In such cases, the bankrupt debtor was directly involved in creating the guarantee relationship. The guarantor's expectation of being able to set off is considered reasonable and is protected by the general principle of Article 67.

- Non-Commissioned Guarantor: The situation of a non-commissioned guarantor is different. If such a guarantor, based on a guarantee agreement entered into before bankruptcy without the debtor's request or involvement, makes a payment after the debtor's bankruptcy and then seeks to set off the resulting recourse claim, allowing this set-off would be problematic. The Court reasoned that this would be tantamount to recognizing a preferentially treated claim that was effectively "created" or brought into a set-off position without the bankrupt debtor's will or any pre-existing legal cause directly linking the guarantor's specific payment to a justifiable expectation of set-off against the bankrupt's assets in a way that should bind other creditors. The expectation of set-off in such a scenario, from the perspective of the bankrupt's estate and the principle of creditor equality, is significantly weaker and less justifiable than in the case of a commissioned guarantee.

- Analogy to Acquiring Third-Party Claims (Article 72(1)(i)): The Supreme Court found that the act of a non-commissioned guarantor making a payment after bankruptcy commencement and thereby acquiring a recourse claim which then creates a state of mutual indebtedness ripe for set-off is analogous in its effect to a person who already owes a debt to the bankrupt going out and acquiring a bankruptcy claim from another person after bankruptcy proceedings have started, for the purpose of creating a set-off opportunity. In both scenarios, a set-off position materializes post-commencement, largely without the bankrupt's pre-bankruptcy intent or direct involvement in establishing that specific set-off dynamic for that particular creditor. The Court viewed this as conflicting with the bankruptcy principle of ensuring fair and equal treatment among creditors.

- Conclusion on Set-Off for Non-Commissioned Guarantors: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that when a non-commissioned guarantor makes a payment under a guarantee agreement (even if that agreement was concluded pre-bankruptcy) after the principal debtor's bankruptcy proceedings have commenced, the guarantor's resulting recourse claim against the bankrupt debtor, while qualifying as a bankruptcy claim, cannot be used as an active claim for set-off against a pre-existing debt owed by the guarantor to the bankrupt. This prohibition arises from an analogous application (類推適用 - ruisui tekiyō) of Bankruptcy Act Article 72, paragraph 1, item (i).

Two Justices provided supplementary opinions. Justice Sudoh emphasized the concept of "substantive equality" in bankruptcy, arguing that set-off should be permitted only when there is a "justifying basis" for such preferential treatment, reflecting the dominant understanding within the business community. Justice Chiba explored the nature of non-commissioned guarantees, suggesting they might be akin to negotiorum gestio (management of another's affairs without a mandate), which could influence the analysis of when the recourse claim truly "arises" for set-off purposes, though the majority opinion based its conclusion on the timing of the guarantee agreement for establishing the claim as a bankruptcy claim.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This 2012 Supreme Court decision is a significant development in Japanese set-off law within bankruptcy:

- Clarifies Status of Non-Commissioned Guarantor's Post-Commencement Recourse Claim: It confirms that such a claim is indeed a "bankruptcy claim" if the underlying guarantee agreement was made pre-bankruptcy.

- Restricts Set-Off by Analogy to Acquisition of Third-Party Claims: The core impact of the decision is its prohibition of set-off for these claims by analogous application of Article 72(1)(i). This significantly curtails the ability of non-commissioned guarantors to achieve preferential recovery through set-off if they only pay the guaranteed debt after the principal debtor is already in bankruptcy.

- Reinforces the Principle of Creditor Equality: The ruling strongly upholds the fundamental bankruptcy principle of ensuring fair and equal treatment among creditors by preventing what it views as the post-commencement creation of a preferential set-off opportunity not directly sanctioned by the bankrupt's pre-crisis actions.

- Emphasizes "Reasonable Expectation of Set-Off" and Debtor's Involvement: The decision, particularly when read alongside other contemporary Supreme Court rulings on set-off (like the 2014 investment trust case, "BK67"), highlights that the courts will carefully scrutinize whether a creditor had a legitimate and "reasonable" expectation of set-off that was formed based on pre-crisis dealings directly involving the bankrupt's will or active participation. A non-commissioned guarantee, undertaken without the debtor's request, generally lacks this crucial element from the bankrupt debtor's perspective, making the guarantor's expectation of set-off less protectable against the interests of the general creditor body.

- Clearly Distinguishes from Commissioned Guarantees: The judgment explicitly differentiates the treatment of non-commissioned guarantors from that of commissioned guarantors regarding set-off rights for post-commencement recourse claims. The bankrupt's prior commission is seen as a key factor justifying the protection of the commissioned guarantor's set-off expectation.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's May 28, 2012, decision provides important clarity on a nuanced aspect of set-off rights in Japanese bankruptcy. It establishes that while a recourse claim acquired by a non-commissioned guarantor due to a post-bankruptcy payment (under a pre-bankruptcy guarantee) is a valid bankruptcy claim, it generally cannot be used to set off against the guarantor's pre-existing debt to the now-bankrupt principal debtor. This conclusion, reached through an analogous application of the statutory rule prohibiting set-off with third-party claims acquired after bankruptcy commencement, reflects a strong judicial commitment to upholding the principle of creditor equality. It underscores that preferential treatment via set-off will be carefully scrutinized and generally disallowed where the set-off opportunity arises from post-commencement events that were not directly rooted in the bankrupt debtor's pre-crisis intentions or actions in creating that specific reciprocal obligation with the setting-off creditor.