Selling Stolen Goods to the Victim: A Japanese Ruling on the Crime of "Arranging Disposal"

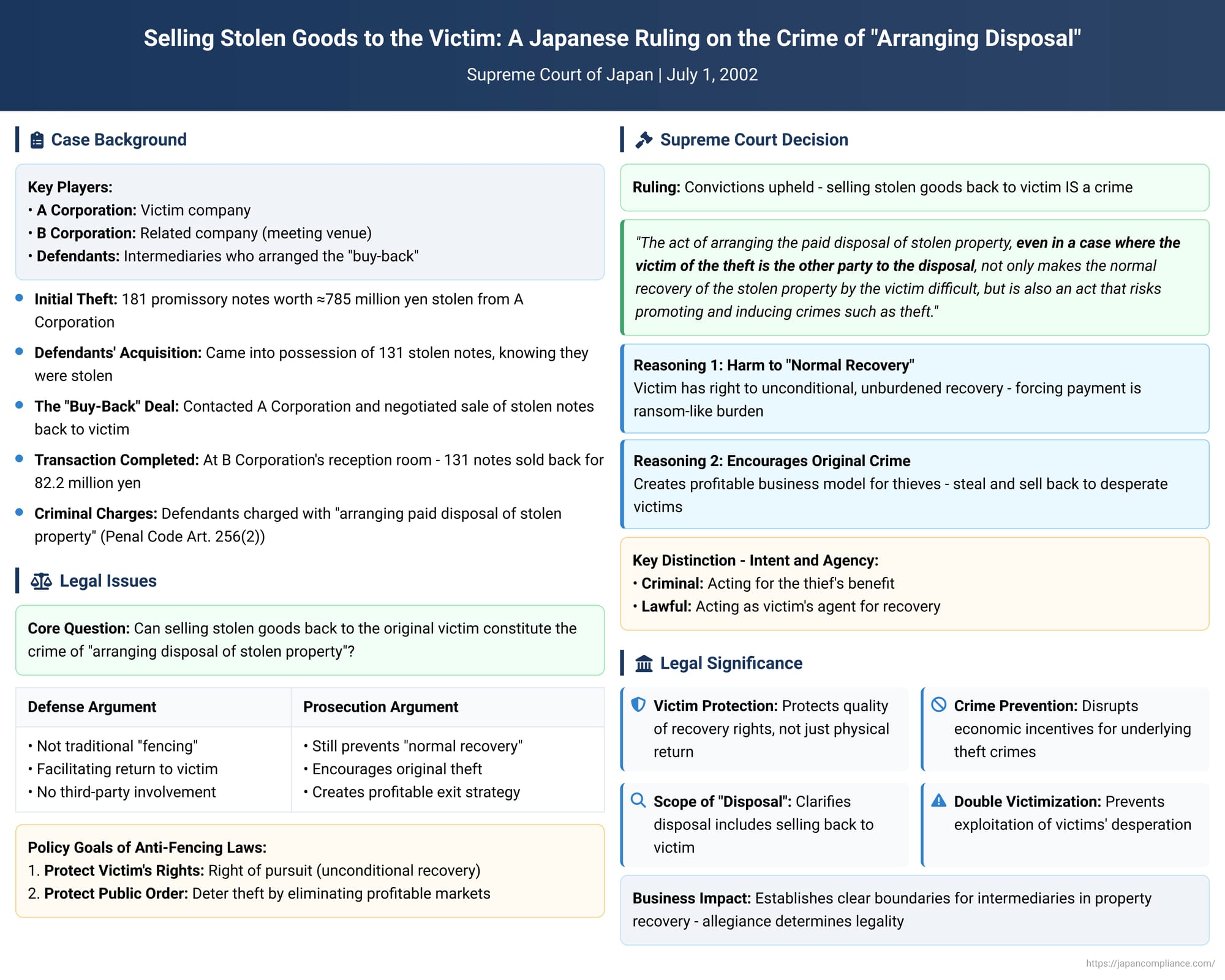

Imagine a company has valuable property stolen—not cash, but something with unique value to the company itself, like sensitive documents or, in this case, a batch of high-value promissory notes. A few days later, an intermediary contacts them. They have the stolen items and can arrange for their return, but for a hefty price. If the company agrees and pays to get its own property back, has the intermediary committed a crime? Can the act of "arranging the disposal" of stolen goods include the paradoxical act of selling them back to the original victim?

This question, which pits a victim's desire for recovery against the criminal law's goal of suppressing black markets, was the subject of a definitive ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 1, 2002. The Court's decision established that selling stolen goods back to the victim is indeed a crime, clarifying that the law protects not just the possession of property, but the victim's right to a "normal," unburdened recovery.

The Facts: The Stolen Promissory Notes

The case began when A Corporation had 181 promissory notes, with a total face value of approximately 785 million yen, stolen from its premises. The defendants in the case came into possession of 131 of these stolen notes, knowing they were the proceeds of the theft.

Instead of attempting to sell the notes on the black market, the defendants and their co-conspirators concocted a different plan: they would sell the notes back to the victim. They contacted individuals related to A Corporation and negotiated a "buy-back" deal. At a meeting in the reception room of a related company, B Corporation, they completed the transaction, handing over the 131 stolen promissory notes in exchange for 82.2 million yen in cash.

The defendants were charged with and convicted of "arranging the paid disposal of stolen property" (tōhin-tō yūshō shobun assen) under Article 256, Paragraph 2 of the Penal Code. On appeal, they argued that their actions should not be a crime. They were not fencing the goods to an unrelated third party; they were facilitating the return of the property to the victim. The High Court rejected this, reasoning that selling stolen goods back to the victim still makes their unconditional, free recovery impossible and, moreover, encourages the original theft by creating a profitable exit strategy for the thieves.

The Legal Framework: The Crime of Dealing in Stolen Property

The crime of dealing in stolen property, often known as "fencing" in common law jurisdictions, is designed to achieve two main policy goals:

- To Protect the Victim's Rights: The law protects the victim's "right of pursuit" (tsuikyū-ken), which is their ongoing legal right to recover their stolen property.

- To Protect Public Order: The law aims to deter the underlying property crimes (like theft) by shutting down the market for stolen goods. If thieves cannot easily profit from their crimes, the incentive to commit them is reduced. This is known as the "promotion of the main offense" (honhan josai-sei) aspect.

The defendants' argument essentially forced the Supreme Court to decide which of these purposes was paramount and how they applied in the unique scenario of selling stolen property back to its owner.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Harm to "Normal Recovery"

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, providing a clear and direct answer to the legal question. The Court's official opinion stated:

"The act of arranging the paid disposal of stolen property, even in a case where the victim of the theft is the other party to the disposal, not only makes the normal recovery of the stolen property by the victim difficult, but is also an act that risks promoting and inducing crimes such as theft."

Therefore, the Court concluded, such an act squarely falls under the definition of "arranging the paid disposal" of stolen property and is a crime.

Analysis: What is a "Normal Recovery"?

The Court's two-pronged justification provides a robust framework for understanding the crime. The first prong—that the act makes "normal recovery" difficult—is particularly insightful.

"Normal recovery" does not simply mean getting the physical item back. It means recovering the property in the way a rightful owner should: unconditionally and without an unreasonable burden. Forcing a victim to pay what amounts to a ransom for their own property is the very definition of an unreasonable burden. The crime, therefore, is not just about the location of the property but about the infringement on the quality of the victim's recovery right. The victim has a right to get their property back for free; forcing them to pay for it is a direct harm to that right.

This logic also supports the second prong of the Court's reasoning. If a profitable business model emerges where thieves can steal property and then sell it back to desperate victims, it creates a powerful financial incentive for the original crime of theft. Punishing the intermediaries who arrange these "buy-backs" is essential for disrupting this criminal ecosystem and upholding the law's goal of preventing the underlying property crimes.

Drawing the Line: The Good Samaritan vs. The Fence

This ruling, while logical, could create a chilling effect if applied too broadly. What about a well-intentioned person—a lawyer, a private investigator, or a friend—who acts on the victim's behalf to negotiate the return of stolen property? Does this person also risk being charged as a criminal fence?

The key distinction, as clarified in legal commentary and other case law, lies in intent and agency.

- The Criminal Act (Acting for the Thief): The crime is committed when the intermediary is acting to benefit the original thief. Their purpose is to help the thief profit from their crime by extorting a payment from the victim. In this 2002 case, the defendants were clearly acting in concert with the thieves to sell the notes, not on behalf of the victim company.

- The Lawful Act (Acting for the Victim): If an intermediary is retained by and acting as the agent of the victim, their actions are not criminal. Their purpose is not to help the thief profit, but to help the victim recover their property. A lower court case involving a person who helped a temple negotiate the return of a stolen treasure established this principle, finding the person not guilty because they acted solely for the benefit of the victim.

The determining factor is allegiance. An intermediary working for the thief is a fence. An intermediary working for the victim is an agent performing a legitimate service.

Conclusion: Protecting Victims from Being Victimized Twice

The 2002 Supreme Court decision is a crucial ruling that protects victims of theft from being exploited a second time. It establishes that the "disposal" of stolen property criminally includes the act of selling it back to its original owner.

The ruling affirms that the law protects not only a victim's physical possession of their property but also their right to a "normal"—that is, unburdened and unconditional—recovery. By criminalizing the act of arranging what is effectively a ransom payment, the Court simultaneously disrupts the economic incentives for the underlying theft and ensures that those who would profit from a victim's desperation are held accountable under the law.