Selling Below Market: Japanese Supreme Court Clarifies Corporate Tax on Low-Value Asset Transfers

Date of Judgment: December 19, 1995

Case Name: Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成6年(行ツ)第75号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

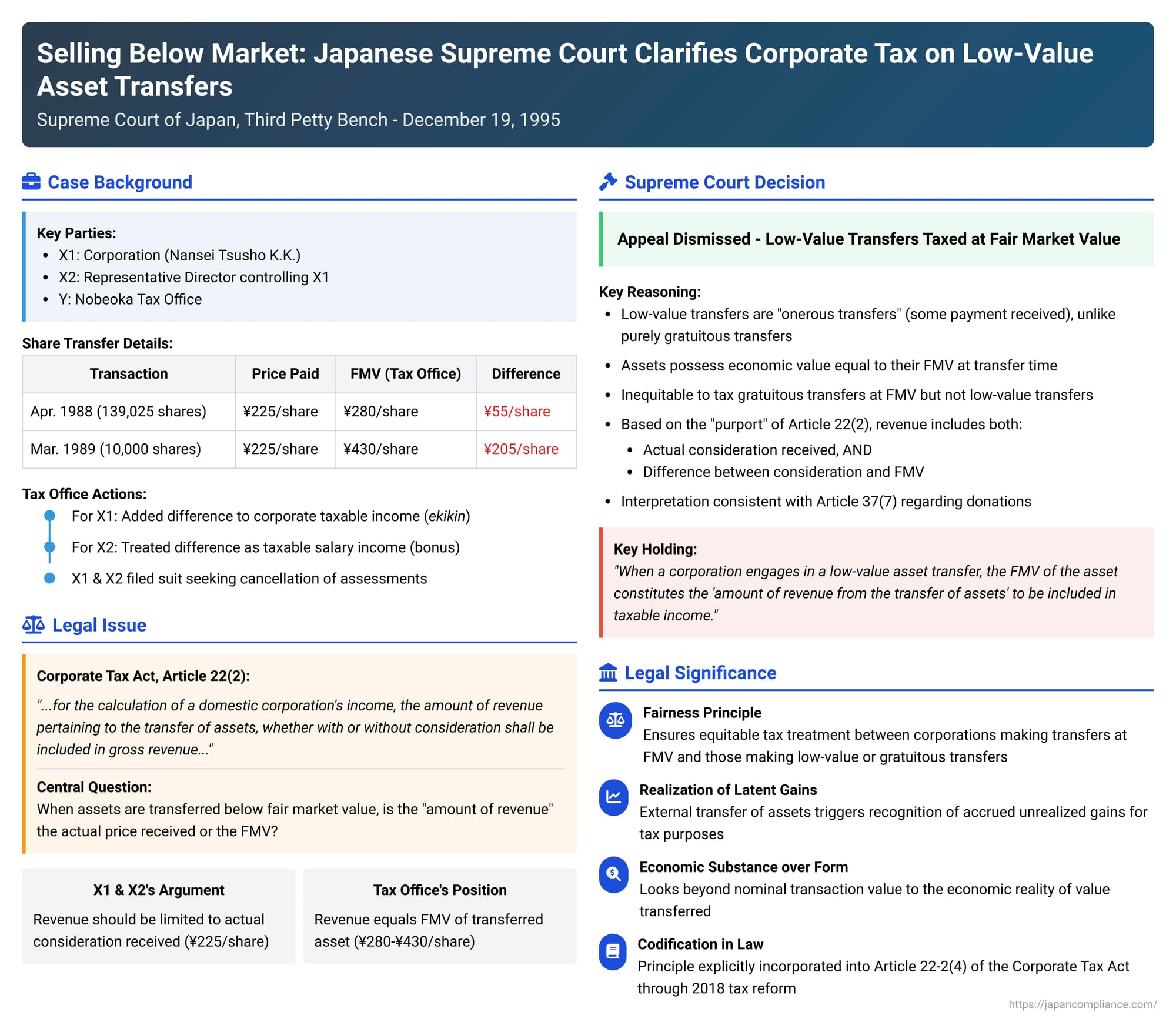

In a significant ruling on December 19, 1995, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the critical issue of how a corporation's taxable income should be calculated when it transfers assets at a price substantially below their fair market value (FMV), particularly to a related party. The decision clarifies the interpretation of Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act, establishing that in such "low-value transfers," the corporation must recognize income based on the asset's FMV at the time of transfer, not merely the inadequate consideration actually received.

The Factual Backdrop: A Below-Market Share Sale to the President

The case involved a company, X1 (Nansei Tsusho Kabushiki Kaisha), engaged in finance and other businesses. X2, an individual, was X1's representative director and had, in effect, provided all of X1's capital, essentially controlling its management.

Between 1980 and 1986, X1 had acquired 149,025 shares of stock in an unrelated bank ("the subject shares") at prices ranging from ¥210 to ¥230 per share, with an average acquisition cost of approximately ¥225 per share. These shares were not publicly traded at the time of the subsequent transfers.

X1 transferred these shares to X2 in two tranches:

- On April 1, 1988, 139,025 shares were sold to X2 at ¥225 per share.

- On March 31, 1989, the remaining 10,000 shares were sold to X2, also at ¥225 per share.

The head of the Y tax office (Nobeoka Tax Office) reviewed these transactions and determined that they were low-value transfers, as the ¥225 per share price was below the FMV of the shares on the respective transfer dates. The tax office assessed the FMV at ¥280 per share for the April 1988 transfer and ¥430 per share for the March 1989 transfer.

Consequently, Y took the following actions:

- For X1 (the corporation): The tax office issued a corrective assessment, asserting that the difference between the FMV of the shares and the actual transfer price should be included in X1's taxable income (益金 - ekikin, meaning gross revenue or profit for tax purposes) under Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act.

- For X2 (the individual director): The tax office determined that X2 had received an economic benefit equivalent to the difference between the FMV and the price he paid for the shares. This benefit was assessed as salary income (specifically, a bonus) for X2.

X1 and X2 disputed these assessments and, after unsuccessful administrative appeals, filed a lawsuit seeking their cancellation.

The Legal Issue: Defining "Revenue" under Corporate Tax Act Article 22(2)

The core of the dispute lay in the interpretation of Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act. This provision states, in essence, that for the calculation of a domestic corporation's income for each business year, "the amount of revenue ... pertaining to ... the transfer of assets, whether with or without consideration" shall be included in the amount of ekikin (gross revenue).

The central question was: when assets are transferred for a price that is below FMV but still involves some payment (an "onerous" but low-value transfer), what constitutes the "amount of revenue" for the transferring corporation? Is it limited to the actual (low) consideration received, or should it be the FMV of the assets?

The appellants (X1 and X2) argued that the transfers were onerous, and in such cases, the "amount of revenue" should be the actual proceeds received by the company. They contended that there was no provision in the Corporate Tax Act to deem FMV as revenue in a low-value onerous transfer and that such transactions could not be artificially split into an FMV sale component and a gratuitous component.

The first instance court (Miyazaki District Court) had taken a different view, ruling against X1 and X2. It posited that Article 22(2) covers income from gratuitous transactions as well, and in such cases, FMV is recognized as income. It reasoned that treating low-value transfers as effectively including a gratuitous component (the difference between FMV and the low price) and taxing this difference at the corporate level was necessary for fairness, to prevent avoidance of tax on asset appreciation. The court considered Article 22(2) a constructive provision that deems income to arise even from gratuitous transactions to maintain equity with those who transact at normal market prices. It further suggested that the term "gratuitous transfer" in Article 22(2) should encompass low-value transfers, aligning with Article 37(6) (now 37(7)) of the Corporate Tax Act, which treats the difference between FMV and the low price in such transfers as a donation for tax purposes. The appellate court upheld this reasoning.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Aligning Low-Value Transfers with Gratuitous Transfers for Fairness

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, ultimately affirming the tax office's position but with a slightly nuanced reasoning compared to the first instance court. The Court ruled that the revenue to be recognized by the corporation in a low-value transfer is indeed the FMV of the transferred asset.

The Supreme Court's reasoning unfolded as follows:

- Baseline for Gratuitous Transfers: The Court first affirmed the principle that Article 22, paragraph 2 requires the inclusion of revenue equivalent to the asset's fair and proper value at the time of transfer when a corporation makes a purely gratuitous transfer (i.e., a transfer for no consideration at all). The provision explicitly recognizes that even asset transfers "without consideration" generate taxable revenue.

- Nature of Low-Value Transfers: The Court clarified that a low-value transfer—one made for consideration that is less than the FMV—is, "needless to say," an "onerous transfer of assets" (a transfer with consideration) within the meaning of Article 22, paragraph 2. This classification differs from the first instance court, which had leaned towards treating low-value transfers as falling under the "gratuitous transfer" category for the purpose of applying FMV.

- Economic Value and the Fairness Imperative: Despite being an onerous transaction, the Court emphasized that the asset transferred still possesses an economic value equivalent to its FMV at the time of transfer. If, in the case of a low-value transfer, only the actual (low) consideration received were recognized as revenue, and the difference between this low price and the FMV were ignored, it would lead to an inequitable outcome when compared to the tax treatment of purely gratuitous transfers (where the full FMV is recognized as revenue). This would create an unfair imbalance.

- Purport of the Provision: Therefore, the Court concluded, based on the "purport of the said provision" (Article 22, paragraph 2), that the amount of revenue to be included in ekikin for a low-value transfer must encompass not only the actual consideration received but also the difference between that consideration and the asset's FMV at the time of transfer. Essentially, the total recognized revenue is the FMV.

- Consistency with Donation Rules: The Court noted that this interpretation is consistent with Article 37, paragraph 7 (now paragraph 8) of the Corporate Tax Act. This article stipulates that in the case of a low-value transfer of assets, the difference between the FMV of the asset and the actual consideration received, to the extent it is deemed to be a substantial gift, is included in the amount of donations made by the corporation (which has implications for the deductibility of donations).

In sum, the Supreme Court held that when a corporation engages in a low-value asset transfer, the FMV of the asset at the time of transfer constitutes the "amount of revenue from the transfer of assets" to be included in its taxable income under Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act.

Key Principles from the Ruling

This landmark decision underscores several important principles in Japanese corporate tax law:

- Fairness Principle: A fundamental rationale behind the ruling is the need to ensure fairness and equity among taxpayers. If corporations could transfer appreciated assets at artificially low prices without recognizing the full gain, it would create an imbalance compared to corporations that transact at FMV or make purely gratuitous transfers where FMV is taxed. The first instance court referred to this as the "proper income calculation theory" (適正所得算出説 - tekisei shotoku sanshutsu setsu).

- Realization of Latent Gains upon External Transfer: The Supreme Court's stance, consistent with prior rulings like the Showa 41.6.24 Mutual Taxi case, suggests that the point at which an asset is transferred outside the corporation is the appropriate moment to recognize any accrued unrealized gains (the "hidden asset value") for tax purposes. This "liquidation" of latent gains occurs regardless of whether adequate consideration is received. Recognizing this gain at the corporate level (X1 in this case) is crucial before assessing the benefit received by the transferee (X2).

- Economic Substance over Form (to an extent): While the Court acknowledged the transaction was "onerous" in form (some payment was made), it looked to the economic reality that an asset worth its FMV had left the corporation. The corporation's taxable income must reflect this outflow of economic value to prevent tax avoidance and ensure proper accounting of corporate assets and profits.

Codification and Subsequent Developments

The principle established by this 1995 Supreme Court judgment regarding the taxation of low-value transfers at FMV was later explicitly incorporated into the Corporate Tax Act through the 2018 (Heisei 30) tax reforms. Article 22-2, paragraph 4 of the Act now clearly stipulates that the amount of revenue from the transfer of assets is the "value of the transferred assets at the time of their delivery". This "value" is generally interpreted as the FMV that would be agreed upon in an arm's-length transaction between third parties.

Implications for X2 (the Individual Recipient)

While the Supreme Court's judgment focused primarily on the corporate tax liability of X1, the case also has direct implications for the recipient of the low-value transfer, X2. As noted in the facts, the tax office determined that the economic benefit X2 received—the difference between the FMV of the shares and the significantly lower price he paid—constituted salary income (specifically, a bonus) taxable to him as an individual. This approach is standard in Japanese tax practice when a director or employee receives an economic benefit from their company due to a non-arm's-length transaction. The taxation of X2 ensures that the full economic value that has shifted from the corporation to the individual is accounted for within the tax system, either as corporate profit or as individual income.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1995 decision in this case delivered a clear message: corporations cannot sidestep the taxation of accrued gains on their assets by transferring them to related parties, or indeed any party, at artificially deflated prices. The principle that revenue from asset transfers should be recognized at fair market value is paramount for ensuring tax equity and the proper reflection of corporate income. This ruling solidified an important anti-avoidance doctrine that has since been formally enshrined in statutory law, underscoring the tax authorities' and courts' focus on the economic substance of transactions, particularly those involving closely held companies and their insiders.