Self-Defense vs. Retaliation: A 1994 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Group Altercations

Case Title: Shōgai Hikoku Jiken (Case Concerning Bodily Injury)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Date of Judgment: December 6, 1994

Case Number: 1990 (A) No. 335

Introduction: The Line Between Defense and Aggression in Group Violence

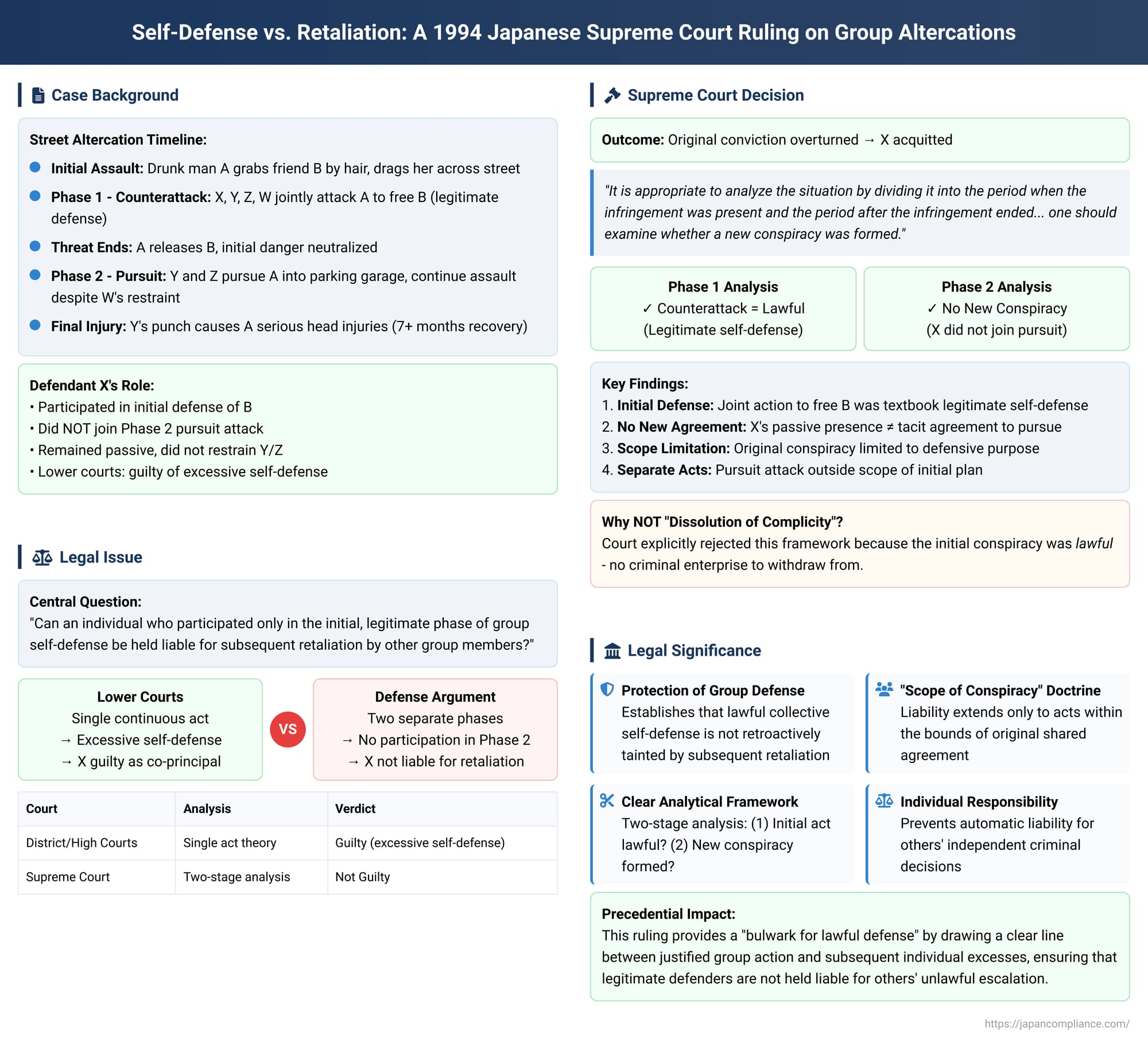

Group altercations present some of the most challenging scenarios in criminal law. They often begin as a response to an unprovoked attack, where a collective act of self-defense is not only understandable but legally justified. But what happens when the tide turns? When the initial threat is neutralized, but some members of the defending group, caught in the heat of the moment, continue the assault, transforming a lawful defense into an unlawful act of retaliation?

Is an individual who participated only in the initial, legitimate phase of the defense criminally liable for the subsequent excesses of their peers? Does their justified act become retroactively tainted, making them a party to "excessive self-defense"? Or does the law draw a sharp line between the two phases?

This critical question was the focus of a landmark 1994 Supreme Court of Japan decision. The case involved a group of friends who came to the defense of another, only for the situation to escalate after the danger had passed. The Court's judgment provides a vital analytical framework for distinguishing between shared, lawful self-defense and a subsequent, separate act of aggression, ultimately hinging on the "scope" of the initial defensive conspiracy.

Factual Background

The incident involved a group of friends and a drunken stranger on a city street at night. The parties were:

- The Group: Defendant X and his friends Y, Z, and W, along with a female companion, B.

- The Aggressor: A, a man in a state of intoxication.

The events unfolded in two distinct phases:

Phase 1: The Lawful Counterattack (Hangeki-kōi)

While X and his friends were talking on a sidewalk, they had a verbal altercation with A, who was passing by. The situation escalated dramatically when A, without provocation, grabbed their friend B by her hair and began dragging her around. To stop this violent and ongoing assault on B, X, Y, Z, and W intervened collectively, punching and kicking A to force him to release B. A, however, maintained his grip on B's hair, dragged her across a wide street, and into the entrance of a parking garage. The four men pursued him, continuing to strike him in their effort to free B. Finally, A let go of B's hair. At this moment, the "imminent and unlawful infringement" that justifies self-defense had ceased.

Phase 2: The Unlawful Pursuit Attack (Tsuigeki-kōi)

After releasing B, A, still belligerent, hurled insults at the group and acted as if he was ready to continue fighting, backing away into the parking garage. The group of four men followed. At this point, the actions of the group members diverged significantly:

- The Aggressors: Y and Z, provoked by A's taunts, attempted to punch A again.

- The Peacemaker: W actively intervened, physically restraining both Y and Z to stop their attacks.

- The Passive Participant: X did not join Y and Z in their new assault. However, unlike W, he did not take any steps to stop them either. He remained present but passive.

Despite W's efforts, Y ultimately broke free and landed a powerful punch to A's face, causing A to fall, hit his head on the concrete, and suffer serious injuries requiring over seven months of medical treatment.

The lower courts treated the entire incident, from the initial defense of B to the final punch by Y, as a single, continuous act. They found X guilty as a co-principal in a crime of bodily injury, mitigating the sentence on the grounds that it was an act of "excessive self-defense" (kajō bōei). The defendant, X, appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing he should not be held responsible for an attack in which he did not participate.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Two-Stage Analysis

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and acquitted X in a judgment that reshaped the understanding of group self-defense. The Court flatly rejected the idea of treating the events as one indivisible act. Instead, it mandated a clear, two-stage analysis.

The Court's core legal principle was articulated as follows:

"In a case like this, where multiple persons jointly engage in an act of defense as a response to an infringement by another party, and after the infringement has ended, some of those persons continue to commit assault, when considering the applicability of self-defense for a person who did not commit the later assault, it is appropriate to analyze the situation by dividing it into the period when the infringement was present and the period after the infringement ended. If the assault during the period of present infringement is recognized as legitimate self-defense, then for the assault after the infringement ended, one should not examine whether the person withdrew from the joint intent of the defensive act, but rather whether a new conspiracy was formed. Only when the formation of a new conspiracy is recognized should the entire series of acts... be considered as a whole to examine the appropriateness of the act as a defense."

Applying this framework, the Court found:

- The Counterattack was Lawful: The initial joint action taken by X and his friends to free B from A's dangerous assault was a textbook case of legitimate self-defense (specifically, defense of a third party). The force used was not, in itself, disproportionate to the threat. Therefore, this act was lawful and not a crime.

- No New Conspiracy for the Pursuit Attack: The Court then examined whether X had entered into a new conspiracy with Y and Z to attack A after the threat to B had ended. It meticulously reviewed the evidence and found none. The lower court had relied on a statement by X that "the four of us advanced as if to corner [A]," but the Supreme Court found this to be inconsistent with the objective facts, noting the parking garage had two exits and W's peacemaking actions demonstrated a lack of unified intent. The pursuit was motivated by Y and Z's anger at A's insults, a motive not necessarily shared by X. X's passivity—his failure to stop Y and Z—was not, by itself, sufficient to prove a tacit agreement to join their assault.

Since the first act was lawful and there was no new conspiracy for the second, unlawful act, X bore no criminal responsibility for the injuries A sustained. He was found not guilty.

The Legal Principle: The "Scope of the Conspiracy"

The 1994 judgment is a masterful application of the "scope of the conspiracy" (kyōbō no shatei) doctrine. This theory holds that a person's liability as a co-conspirator only extends to acts that fall within the bounds of their shared, original agreement.

In this case, the initial conspiracy was formed for a specific and lawful purpose: to defend B from A's imminent and unlawful attack. The scope of this "defensive conspiracy" was inherently limited to actions necessary to neutralize that threat.

The subsequent pursuit attack was fundamentally different in nature and motive:

- Objective Situation: It occurred after the threat had ceased. A was no longer assaulting B.

- Motive: It was driven not by defense, but by anger and retaliation in response to A's insults.

Because the pursuit attack fell outside the scope of the original defensive plan, liability for it could not be automatically imputed to all original participants. Instead, the prosecution had to prove that those who participated in the second phase did so based on a new conspiracy, formed with a new, unlawful intent.

This analytical framework is crucial. It prevents the law from retroactively tainting a legitimate act of defense with the subsequent, independent wrongdoing of others. It protects individuals who join in a common cause for a lawful purpose from being held responsible when their partners-in-defense unilaterally decide to cross the line into criminal aggression.

Why Not "Dissolution of Complicity"?

It is telling that the Supreme Court explicitly instructed lower courts not to use the "dissolution of complicity" framework in this type of case. The dissolution analysis, as seen in the 1989 and 2009 rulings, asks whether a participant in an unlawful conspiracy did enough to sever their causal link to the crime.

That framework is ill-suited here for a simple reason: the initial conspiracy was lawful. There was no criminal enterprise for X to "withdraw" from. As one major academic theory suggests, since the counterattack was justified, it did not satisfy the elements of a criminal offense, meaning no co-principal relationship for a crime was ever formed in the first place. The Supreme Court's approach effectively adopts this logic. The proper starting point is not to assume a single, overarching criminal plan, but to ask whether there was any criminal plan at all, and if so, what its specific boundaries were.

Applying the strict causal severance test from the other cases would likely have led to the conviction of X. He was physically present, and his inaction could be seen as a failure to take preventative measures to undo the "dangerous situation." The Court's choice to use the "scope of conspiracy" analysis instead shows its recognition that different factual scenarios require different legal tools to achieve a just result.

Conclusion: A Bulwark for Lawful Defense

The 1994 Supreme Court decision stands as a critical bulwark protecting the right to collective defense. It establishes that when a group acts together to repel an unlawful attack, their shared intent is presumed to be defensive and lawful in scope. Should some members of the group subsequently embark on a retaliatory course of action, the law will not automatically hold the entire group liable.

Instead, the court will draw a line in the sand at the moment the initial threat ends. Liability for any subsequent violence will attach only to those who can be proven to have formed a new, separate conspiracy to commit an unlawful act. By refusing to let the unlawful excesses of some retroactively contaminate the lawful actions of others, the Court provided an elegant and just solution to one of the most complex problems at the intersection of self-defense and complicity.