Single-Color Trademarks in Japan: Insights from the Louboutin Red-Sole Decision

TL;DR

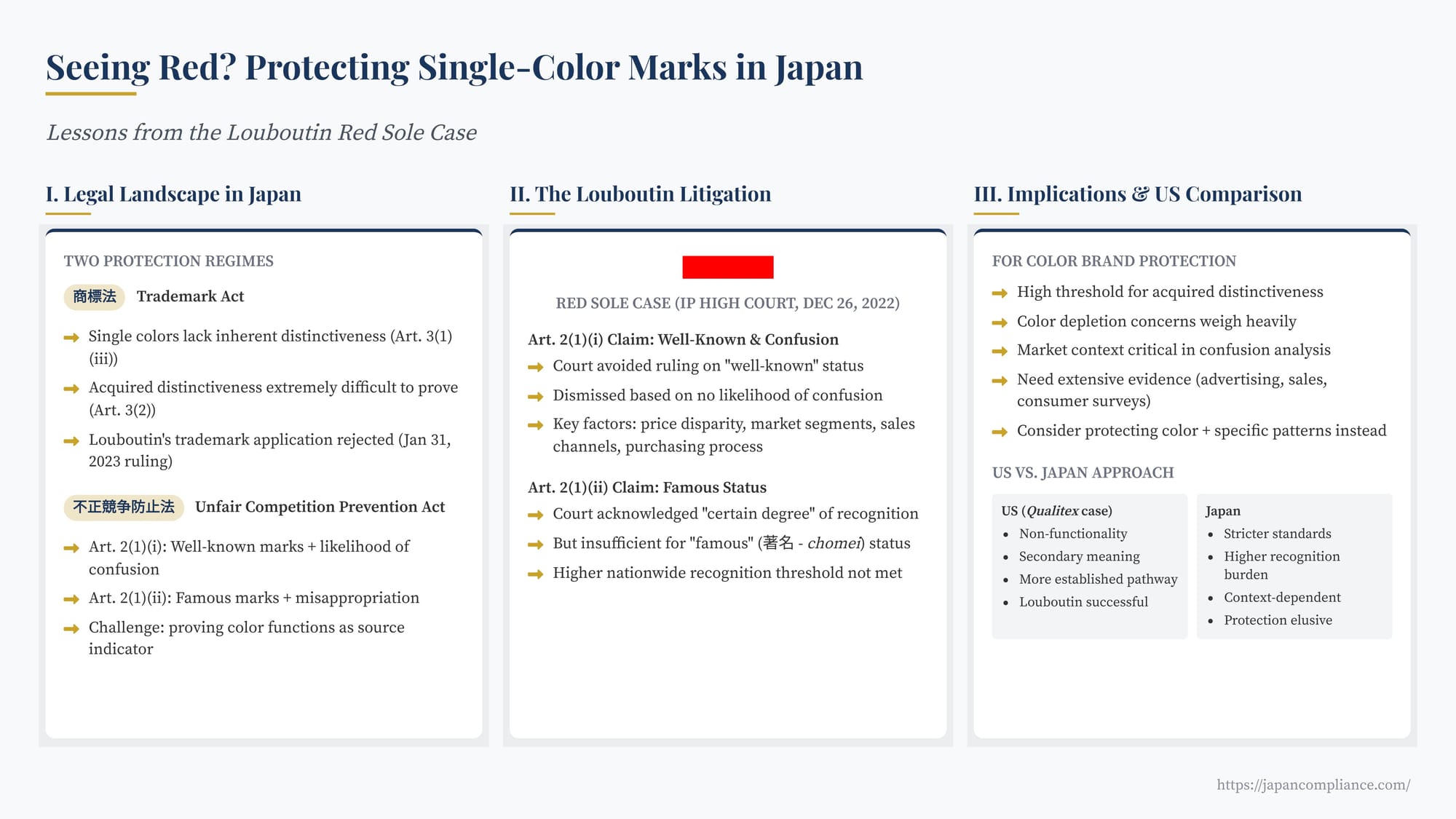

- Japan sets a very high bar for single-color trademarks.

- Louboutin’s red-sole claims failed under both the Trademark Act (no acquired distinctiveness) and the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (no confusion / not “famous”).

- Courts weighed market context (price, channels, other branding) over hue similarity.

- To protect a color in Japan, brands need overwhelming evidence of consumer recognition plus non-functionality, or consider color-shape trade dress instead.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Landscape for Protecting Source Indicators in Japan

- The Louboutin Red-Sole Litigation under the UCPA

- Analysis and Implications for Protecting Color Brands

- Comparison with the US Approach

- Conclusion

Color is a powerful branding tool. Think Tiffany Blue®, UPS Brown®, or Owens Corning Pink®. Companies invest heavily in associating a specific color with their products or services, hoping it will function as a unique identifier – a trademark. However, securing exclusive rights to a single color is notoriously difficult legally, as courts and trademark offices grapple with concerns about depleting the spectrum of available colors and preventing functional features from being monopolized.

This challenge was recently highlighted in Japan through litigation involving the iconic red soles of luxury footwear designer Christian Louboutin. The outcome of cases under both Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act and the Trademark Act provides valuable insights for businesses seeking to protect color branding in the Japanese market.

The Legal Landscape for Protecting Source Indicators in Japan

Businesses seeking to protect branding elements like colors as source indicators in Japan primarily rely on two legal regimes:

- Trademark Act (商標法 - Shōhyōhō): Offers the strongest protection through registration. However, single colors generally face significant hurdles:

- Lack of Inherent Distinctiveness: A single color is typically considered non-distinctive under Article 3(1)(iii) of the Trademark Act, meaning consumers aren't presumed to see it as indicating a specific source.

- Acquired Distinctiveness (Secondary Meaning): Protection may be possible if the applicant can prove the color has acquired distinctiveness through extensive use, advertising, and consumer recognition, specifically linking the color to their goods or services (Article 3(2)). This burden of proof is exceptionally high for single colors in Japan, reflecting a policy concern about granting monopolies over basic colors needed by competitors. In a related case, the Intellectual Property High Court upheld the Japan Patent Office's rejection of Louboutin's application to register the red sole color for shoes (Judgment of January 31, 2023), emphasizing the public interest in keeping colors available for use and the extremely high level of recognition required to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness for a single color mark.

- Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法 - Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō, "UCPA"): Provides protection against certain unfair practices, even without trademark registration. Two provisions are particularly relevant for protecting well-known branding elements:

- Article 2(1)(i): Prohibits using an indication of goods or services (shōhin tō hyōji) that is identical or similar to another party's well-known (shūchi) indication, causing a likelihood of confusion (kondō no osore) among consumers as to the source. "Well-known" generally implies recognition within a specific region or among a particular consumer group.

- Article 2(1)(ii): Prohibits using an indication identical or similar to another party's famous (chomei) indication of goods or services as one's own indication. "Famous" implies a higher level of nationwide recognition than "well-known." This provision primarily aims to prevent dilution or misappropriation of goodwill associated with famous marks and does not strictly require proof of consumer confusion.

The Challenge for Single Colors under UCPA: Similar to trademark law, establishing that a single color functions as an "indication of goods or services" (shōhin tō hyōji) – meaning consumers perceive it as a source identifier – and that it meets the threshold of being "well-known" or "famous" presents significant difficulties under the UCPA.

The Louboutin Red Sole Litigation under the UCPA (IP High Court, Dec 26, 2022)

This case pitted the renowned designer and his company against a Japanese shoe company selling women's high heels featuring red soles made of rubber, distinct from Louboutin's signature lacquered red soles. Louboutin alleged violations of both UCPA Article 2(1)(i) (well-known indication/confusion) and Article 2(1)(ii) (famous indication/misappropriation), arguing the red color applied to the sole of high-heeled shoes served as a distinctive source indicator for his brand.

The Tokyo District Court initially dismissed the claims, finding the red sole indication was neither well-known nor famous, and also finding no likelihood of confusion partly due to differences in appearance (lacquer vs. rubber, gloss) and market factors. Louboutin appealed to the Intellectual Property (IP) High Court.

The IP High Court (Judgment of December 26, 2022) also dismissed the appeal, but its reasoning differed significantly, particularly regarding the claim under Article 2(1)(i).

Analysis of Claim 1: Well-Known Indication / Likelihood of Confusion (Art. 2(1)(i))

- Circumventing the Threshold Question: Establishing that a single color functions as a shōhin tō hyōji (an indication of source) is often the most contentious part of such cases. Rather than tackling this head-on, the IP High Court took a different approach. It decided to first analyze the likelihood of confusion.

- No Likelihood of Confusion Found: The court concluded that there was no likelihood of consumers being confused as to the source of the defendant's shoes. Its reasoning heavily relied on contextual market factors:

- Price Disparity: A significant difference in price points between Louboutin's luxury products and the defendant's more affordable shoes.

- Market Segments & Sales Channels: The products targeted different consumer segments and were sold through different channels.

- Purchasing Process: Consumers buying expensive high heels typically examine them carefully in stores where branding information is readily available (on displays, packaging, and the shoe's insole).

- Other Branding: The presence of distinct brand logos on the defendant's shoes' insoles further reduced confusion risk.

- Outcome: Because confusion was deemed unlikely based on these factors, the court dismissed the claim under Article 2(1)(i) without needing to definitively rule on whether the single red sole color itself actually qualified as a protectable "indication of goods or services" under this provision. This strategic move allowed the court to avoid setting a broad precedent on the inherent protectability of single colors as source identifiers in this specific context.

Analysis of Claim 2: Famous Indication / Misappropriation (Art. 2(1)(ii))

- Assessing "Fame": Unlike its approach under 2(1)(i), the court did address the status of the red sole mark when considering the claim based on "famousness" under 2(1)(ii). This provision requires a higher level of recognition than "well-known."

- Recognition Found Insufficient for "Fame": The court considered survey evidence submitted by Louboutin. It acknowledged that the evidence indicated a "certain degree" (一定程度 - ittei teido) of consumer recognition linking the red sole to the Louboutin brand. However, it concluded that this level of recognition did not meet the high threshold of "famous" (著名 - chomei) required by Article 2(1)(ii). "Famous" under the UCPA generally implies very high, nationwide recognition across a broad spectrum of consumers, akin to truly iconic brand identifiers.

- Outcome: The claim under Article 2(1)(ii) also failed because the red sole mark, while somewhat recognized, was not deemed legally "famous" in Japan.

Analysis and Implications for Protecting Color Brands

The outcomes in both the UCPA litigation and the related trademark rejection case underscore the significant challenges businesses face when seeking to protect single-color marks in Japan.

- High Bar for Single-Color Protection: Japanese courts and the JPO appear reluctant to grant exclusive rights over a single color. Concerns about functionality (is the color essential to the product's use or purpose, or does it affect cost/quality?) and the principle that basic colors should remain available for competitors to use ("color depletion" theory) weigh heavily against protection. Establishing acquired distinctiveness (secondary meaning) requires overwhelming evidence that consumers uniquely associate that specific color, used in that specific way, with only one source.

- "Well-Known" vs. "Famous" Distinction: The IP High Court's differing analysis under the two UCPA provisions highlights the distinct thresholds. Achieving some level of recognition might potentially support a finding of "well-known" (shūchi), although the court deliberately avoided ruling on this. Achieving "famous" (chomei) status demands a much higher, near-universal level of recognition nationwide. This suggests that even strongly recognized color marks might struggle to meet the stricter standard needed for protection against dilution or misappropriation under Article 2(1)(ii).

- The Importance of Context in Confusion Analysis: The court's focus on market realities (price, channels, consumer behavior, other branding) under Article 2(1)(i) is instructive. It shows that even if a non-traditional mark could theoretically be protectable, the likelihood of confusion analysis will heavily depend on how the defendant is using a similar mark in the marketplace. Significant differences in price, product presentation, and target audience can defeat a claim of confusion, even if the marks themselves have similarities.

- Building a Case for Color Protection: For businesses aiming to protect color branding in Japan:

- Gather Extensive Evidence: Proving acquired distinctiveness requires robust evidence accumulated over time. This includes extensive advertising and promotion explicitly linking the color to the brand, significant sales figures demonstrating market presence, evidence of intentional copying by competitors, and, crucially, consumer surveys demonstrating a high level of unique source association with the color.

- Focus on Use: Protection is typically linked to the specific way the color is used (e.g., red sole on high-heeled shoes). Broader claims for a color across various goods might be even harder to sustain.

- Consider Alternatives: Protecting combinations of colors, or a specific color used in conjunction with a distinctive shape or pattern (trade dress), may offer a more viable path than relying on a single color alone under current Japanese practice.

Comparison with the US Approach

The approach in Japan appears stricter than in the United States regarding single-color marks. US trademark law, following the Supreme Court's decision in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co., allows for the registration and protection of single colors as trademarks if they meet two key conditions:

- Non-Functionality: The color must not be functional, meaning it is not essential to the use or purpose of the article and does not affect its cost or quality.

- Acquired Distinctiveness (Secondary Meaning): The color must have acquired secondary meaning, meaning consumers have come to identify the color, as used on the specific goods/services, with a particular source.

Louboutin itself successfully registered its red sole mark in the US after demonstrating secondary meaning and arguing for its non-functionality in the context of high-fashion footwear. While proving secondary meaning for a single color is still challenging in the US, the legal pathway seems somewhat more established and potentially more attainable than the recent Japanese jurisprudence suggests.

Conclusion

The litigation surrounding the Louboutin red sole in Japan provides a clear signal: securing exclusive rights to a single color as a trademark or under unfair competition law faces significant obstacles. While the IP High Court acknowledged some consumer recognition, it ultimately found it insufficient for "famous" status under the UCPA and carefully avoided setting a precedent on whether the color qualified as a "well-known" source indicator by dismissing the relevant claim based on a lack of consumer confusion in the specific market context. Coupled with the high bar set in trademark law for acquired distinctiveness, businesses should approach single-color branding protection strategies in Japan with caution, backed by extensive evidence of consumer recognition and potentially exploring protection for color combinations or broader trade dress elements. The iconic red sole may be recognized, but under current Japanese law, exclusivity remains elusive.

- Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

- Digital Deception or Fair Play? Applying Japan’s Premiums and Representations Act to Online Advertising

- Antitrust Considerations in Japan: Beyond Cartels – Cooperatives, ESG and Human Rights

- JPO – Non-Traditional Trademarks (Color Marks) Guidelines