Security Transfer in Japan: Debtor's Right to Redeem vs. Creditor's Power to Sell After Default

Date of Judgment: February 22, 1994

Case Name: Action for Vacant Possession of House

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

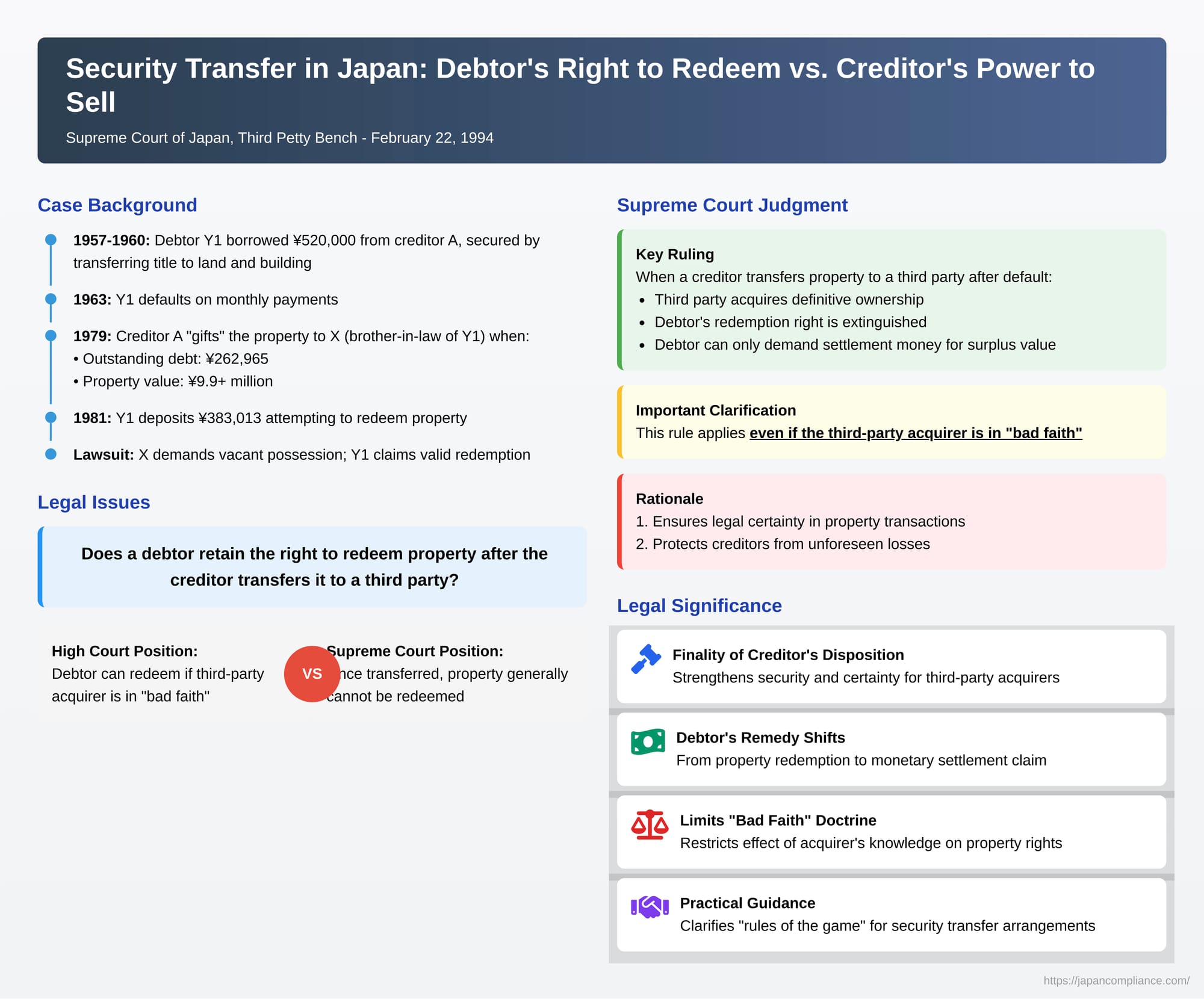

"Security transfer" (jōto tanpo) is a widely utilized, non-statutory form of security in Japan, particularly for real property. In such an arrangement, a debtor transfers legal title of their property to a creditor to secure an obligation. If the debt is repaid, title reverts to the debtor. If the debtor defaults, the creditor can realize their security from the property. A critical question arises concerning the debtor's right to "redeem" (ukemodoshi-ken) the property by repaying the debt after default, especially if the creditor has, in the meantime, transferred the property to a third party. The Supreme Court of Japan provided a landmark ruling on this issue on February 22, 1994, clarifying the limits of the debtor's redemption right once the creditor disposes of the collateral.

The Factual Saga: A Loan, a Security Transfer, a Default, and a "Gift"

The case involved a series of transactions and familial relationships:

- The Original Debt and Security Transfer: By March 21, 1957, Y1 had borrowed ¥520,000 from A. The repayment was scheduled in monthly installments of ¥5,000 until October 1965. To secure this debt, Y1 transferred the ownership of his land ("Lot Alpha") and a building on it ("the Building") to A. An ownership transfer registration, citing "sale" as the cause, was completed in A's name in February 1960. This arrangement, despite its form, was understood to be a security transfer.

- Debtor's Default: Y1 defaulted on his repayment obligations from May 1963 onwards. (There was a period where X, who was A's brother-in-law and also Y1's wife's brother, occupied the Building, and Y1 had moved out. Y1 later won a prior lawsuit against X and regained possession of the Building in October 1978, after which Y1 and his wife, Y2, occupied it).

- Creditor's Transfer to a Third Party (X): On August 29, 1979, A (the original creditor and titleholder under the security transfer) "gifted" Lot Alpha and the Building to X. At this point, the outstanding balance of Y1's debt to A was ¥262,965, while the market value of Lot Alpha and the Building was stated to be not less than ¥9.9 million. The ownership transfer from A to X was registered on August 31, 1979. It was alleged by Y1 that this gift from A to X was primarily orchestrated by X to prevent Y1 from eventually repaying the debt and redeeming the properties, and to make it practically impossible for Y1 to receive any settlement money (surplus value) from A that would normally be due after a disposition of security property.

- Debtor's Attempted Repayment (Deposit): On August 20, 1981, when the outstanding balance of Y1's debt to A was allegedly no more than ¥286,869, Y1 deposited ¥383,013 with a legal deposit office, intending this as full payment of the remaining debt.

- X's Lawsuit for Possession: X, as the registered owner (following the gift from A), filed a lawsuit against Y1 and Y2, demanding vacant possession of the Building (and another building, "Building Beta," also located on the premises) based on his ownership. Y1 and Y2 resisted, arguing that Y1 had validly redeemed the property through the deposit.

The High Court's View: Redemption Possible Against a "Bad-Faith Acquirer"

The District Court had initially ruled in favor of X. However, the High Court reversed this decision concerning the Building. The High Court found that even if a creditor (A) transfers property held under a security transfer to a third party (X) after the debtor's (Y1's) default, if that third-party acquirer (X) is a "bad-faith acquirer acting against good faith" (haishin-teki akuisha – essentially an acquirer whose claim to title is vitiated by their egregious bad faith concerning a prior right or interest), then the debtor (Y1) could still repay the secured debt and redeem the property, provided a final settlement of accounts (seisan) had not yet occurred. The High Court deemed X to be such a bad-faith acquirer and held that Y1's deposit constituted a valid redemption, which Y1 could assert against X even without a new registration of title in Y1's name. X appealed this part of the High Court's decision.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (February 22, 1994): Redemption Right Generally Lost After Creditor Disposes of Collateral

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision regarding the Building and remanded the case. It established a clear general rule regarding the debtor's right of redemption following a creditor's disposition of the collateral to a third party.

- Creditor's Power to Dispose of Collateral After Default: The Court affirmed that in a real property security transfer, if the debtor defaults on the secured obligation, the creditor (who holds legal title as security) acquires the power to dispose of the property. This power exists whether the security transfer agreement contemplates an "attributive settlement" (kizoku seisan gata – where the creditor takes definitive ownership of the property in satisfaction of the debt) or a "disposition settlement" (shobun seisan gata – where the creditor sells the property to a third party and applies the proceeds to the debt).

- Effect of Creditor's Transfer to a Third Party on Redemption Rights: The Supreme Court then laid down the crucial rule: "When the creditor, based on this power [of disposition], transfers the subject property to a third party, as a general rule, the transferee acquires definitive ownership of the subject property. The debtor is then only entitled to demand payment of settlement money from the creditor if there is any surplus, and ceases to be able to redeem the subject property by repaying the remaining debt." (The Court cited its precedents: Supreme Court, October 23, 1974, Minshū Vol. 28, No. 7, p. 1473; Supreme Court, February 12, 1987, Minshū Vol. 41, No. 1, p. 67).

- Irrelevance of the Third Party's "Bad Faith Acting Against Good Faith": Most significantly, the Court held that this loss of the debtor's right of redemption upon transfer to a third party applies even if the third-party acquirer (X) could be characterized as a "bad-faith acquirer acting against good faith".

- Rationale for Disregarding Third Party's Subjective State: The Supreme Court provided two main reasons for this stance:

- Legal Certainty: To hold otherwise (i.e., to allow redemption against such a third party) would mean that "the state of legal relations would continue to be unsettled."

- Protection of the Creditor: It would "give rise to the risk of causing unforeseen loss to the creditor, who is not necessarily in a position to ascertain whether the transferee falls under the category of a bad-faith acquirer acting against good faith." For example, the original creditor (A), believing the disposition to X was final, might not pursue the debt further, potentially allowing it to become time-barred, only to find the disposition later unwound.

- Application to the Case: Based on these principles, when A (the original creditor) gifted the Building to X after Y1's default, Y1 lost the right to redeem the Building by repaying the debt. X acquired definitive ownership. The High Court's decision, which allowed Y1 to redeem against X based on X being a "bad-faith acquirer," was therefore an error in legal interpretation.

- Remand for Consideration of Debtor's Other Defenses: While Y1 lost the right to redeem the property itself, the Supreme Court acknowledged that Y1 still had a right to a monetary settlement if the property's value exceeded the debt. The case was remanded to the High Court for further deliberation on Y1's other potential defenses, specifically including the possibility of Y1 asserting a claim for delivery of the property only in exchange for the payment of any due settlement money by X (or by A, the original creditor, to whom X might be accountable for it). This hints at the debtor's ability to exercise a lien-like right.

The Debtor's Remaining Right: Claim for Settlement Money (Seisan-kin)

This judgment, while cutting off the debtor's right to reclaim the physical property after its disposition to a third party, strongly affirms the debtor's right to a monetary settlement from the original creditor.

- Duty of Settlement (Seisan Gimu): This is a fundamental principle in Japanese security transfer law, established by earlier Supreme Court precedents (e.g., the M94 case: Supreme Court, March 25, 1971, Minshū Vol. 25, No. 2, p. 208). The creditor cannot simply keep the entire property if its fair value at the time of enforcement (either through taking ownership or selling it) exceeds the outstanding debt plus reasonable enforcement costs. The surplus value must be returned to the debtor.

- Disposition to Third Party Does Not Negate Settlement Duty: The 1994 judgment makes it clear that even if the property is transferred to a third party (by sale, or even by gift as in this case, where the gifted property's value is then assessed against the debt), the original creditor's duty to account to the original debtor for any surplus value remains. The debtor's claim simply shifts from a right to redeem the property to a right to receive settlement money.

- Lien-like Defense: The Supreme Court's remand instruction to consider Y1's claim for delivery only in exchange for settlement money is significant. It suggests that the debtor, even when sued for possession by the third-party acquirer, might be able to assert a defense similar to a lien (ryūchi-ken), refusing to give up possession until their claim for settlement money against the original creditor is satisfied or secured. Subsequent Supreme Court case law (e.g., Supreme Court, April 11, 1997, Shūmin No. 183, p. 241) has indeed confirmed that a debtor can assert such a lien for their settlement money claim against a third-party acquirer demanding possession. (However, in Y1's second appeal to the Supreme Court in this very litigation chain, after remand, his claim for an exchange was ultimately denied because his right to claim settlement money was found to have become time-barred by prescription: Supreme Court, February 26, 1999, Hanrei Jihō No. 1671, p. 67).

Understanding "Disposition Settlement" in Security Transfers

This judgment clarifies that the creditor's power of "disposition" to realize their security is broad. It's not limited to a sale that generates cash proceeds. The "gift" from A to X was treated as a form of disposition by the creditor. In such cases, for the purpose of settlement, the property is valued at its fair market price at the time of such disposition, and this value is notionally applied against the debt. The key principle is that the property's economic value is accounted for in settling the debt, and any surplus is due back to the debtor.

Why the Third Party's "Bad Faith" Doesn't Revive the Right to Redeem the Property

The Supreme Court's rejection of the High Court's "bad-faith acquirer" reasoning is pivotal.

- The term "bad-faith acquirer acting against good faith" (haishin-teki akuisha) is a specific concept in Japanese property law, typically used in the context of Civil Code Article 177 (which requires registration to perfect real property rights against third parties). It usually describes a party who, despite knowing of a prior unperfected transfer, attempts to assert their own subsequently perfected right in a manner that is grossly unfair or abusive.

- The Supreme Court essentially found this concept misapplied by the High Court in the context of post-disposition redemption rights under a security transfer. Once the creditor legitimately exercises their power to dispose of the collateral to a third party (thereby realizing the security), the debtor's right to redeem the property itself by repaying the debt is extinguished. The transaction between the creditor and the third party becomes definitive. The focus then shifts to the monetary settlement between the original debtor and the original creditor.

- Allowing the debtor to unwind the creditor's disposition to a third party based on that third party's alleged "bad faith" regarding the debtor's situation would, as the Supreme Court noted, lead to prolonged legal uncertainty and could unfairly prejudice the original creditor, who has a right to finalize the enforcement of their security.

Implications of the Ruling

This 1994 Supreme Court judgment has significant implications:

- Finality of Creditor's Disposition: It strengthens the finality of a creditor's disposition of collateral to a third party once a debtor has defaulted under a real property security transfer agreement. Third-party acquirers from such creditors receive a more secure title, largely free from the risk of the original debtor later attempting to redeem the property.

- Debtor's Remedy Shifts to Monetary Settlement: It clarifies that the debtor's primary remedy after such a third-party disposition is not to reclaim the property but to seek a monetary settlement from the original creditor for any surplus value.

- Limits on "Bad-Faith Acquirer" Doctrine: It curtails the potential for debtors to use allegations of a third-party acquirer's "bad faith" to undo a creditor's otherwise valid disposition of collateral made in exercise of their security rights.

- Guidance for Structuring Transactions: It provides clearer "rules of the game" for creditors, debtors, and third-party purchasers involved in security transfer arrangements.

The judgment does use the phrase "as a general rule" (gensoku toshite) when stating that the debtor's redemption right is lost. Legal commentary accompanying the judgment suggested this might leave room for rare exceptions, for instance, if the creditor's "disposition" to a third party was not an outright transfer of ownership but merely the creation of another, subordinate security interest for that third party. However, the overall thrust of the judgment and subsequent case law points towards a strong principle of finality once an outright disposition to a third party has occurred.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of February 22, 1994, is a crucial decision in the law of security transfers (jōto tanpo). It firmly establishes that when a creditor, after a debtor's default, disposes of real property held as security by transferring it to a third party, the debtor's right to redeem the actual property by repaying the debt is generally extinguished. This holds true even if the third-party acquirer was aware of the circumstances or could be characterized as acting in "bad faith" towards the debtor's desire to redeem. While the debtor loses the ability to reclaim the specific asset, their fundamental right to a monetary settlement from the creditor for any surplus value (the property's fair value less the debt and costs) is preserved. This ruling prioritizes transactional certainty and the finality of security enforcement involving third parties, while still upholding the core principle that a creditor should not be unjustly enriched beyond the satisfaction of the secured debt.