Security by Title Transfer (Jōto Tanpo) in Japanese Corporate Reorganization: Owner or Secured Creditor? A 1966 Supreme Court Ruling

"Security by transfer of title" (譲渡担保 - jōto tanpo) is a long-standing, non-statutory form of security commonly used in Japanese commercial transactions. Under this arrangement, a debtor formally transfers legal title of an asset (movable or immovable) to a creditor to secure an obligation, with the understanding that full title will revert to the debtor upon repayment of the debt. If the debtor defaults, the creditor can typically realize the security, often by definitively acquiring the asset or selling it and settling accounts. A critical question arises when a company that has granted jōto tanpo over its assets enters corporate reorganization proceedings (会社更生手続 - kaisha kōsei tetsuzuki) before the security has been definitively foreclosed or realized. Can the secured creditor, based on their formal legal title, demand the physical return of the collateral by exercising a "right of reclamation" (取戻権 - torimodoshi-ken) as if they were the outright owner? Or are they to be treated like other secured creditors who must participate in the reorganization plan and whose rights might be modified? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental issue in a landmark judgment on April 28, 1966.

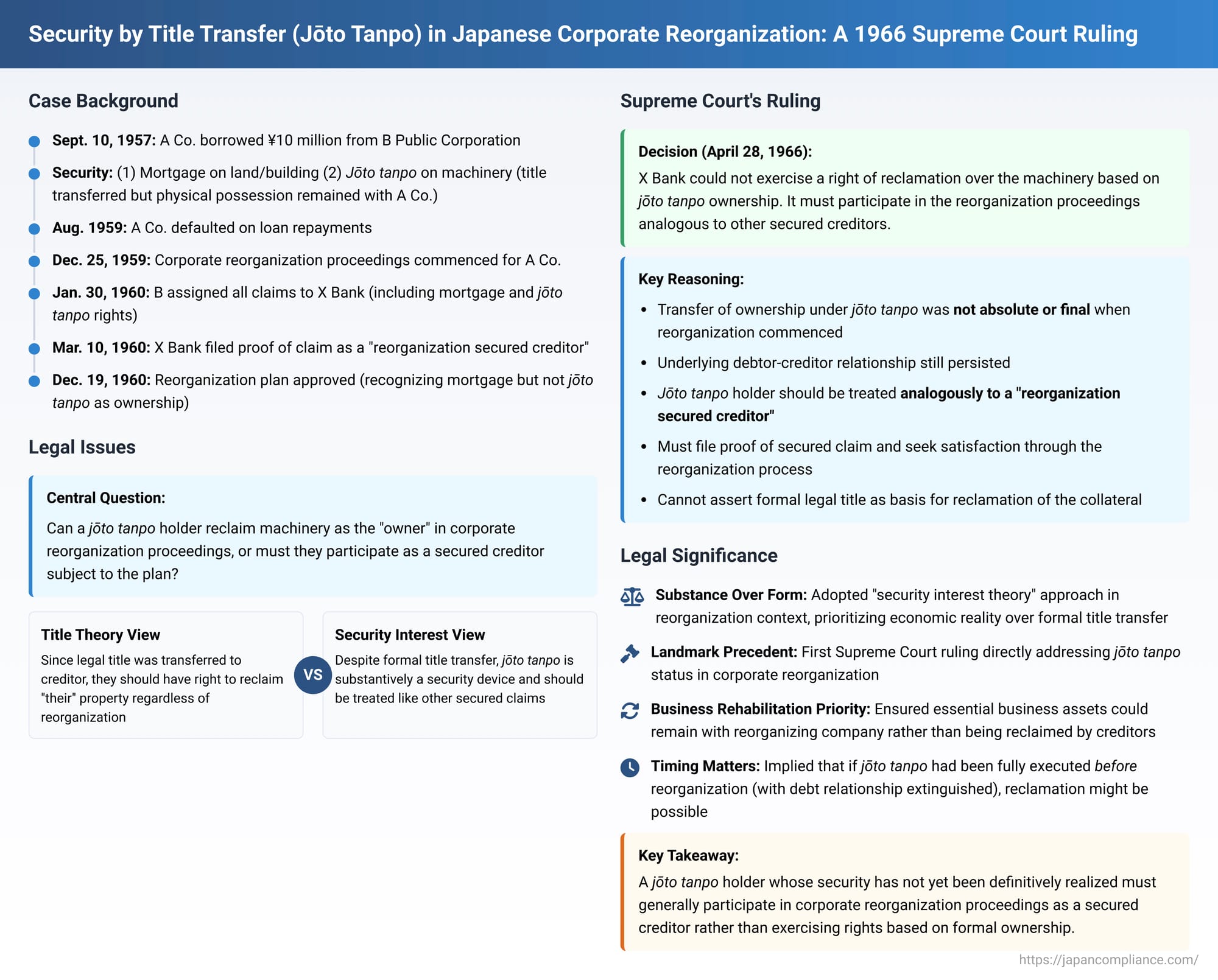

Factual Background: Loan, Jōto Tanpo on Machinery, and Corporate Reorganization

The case involved A Co., which, on September 10, 1957, borrowed 10 million yen from B Public Corporation, agreeing to an installment repayment plan. As security for this loan, A Co. took two key actions:

- It granted B Public Corporation a first-priority mortgage over its land and factory buildings.

- It also provided a jōto tanpo over its factory machinery and equipment. Under this arrangement, legal title to the machinery was formally transferred to B Public Corporation. However, physical possession was constructively transferred to B Public Corporation by means of sen'yū kaitei (a legal fiction where the debtor, A Co., continues to physically possess the asset but now holds it on behalf of the creditor, B Public Corporation). A Co. was permitted to continue using the machinery free of charge but promised to return it upon B Public Corporation's request.

From August 1959 onwards, A Co. defaulted on its loan repayments, thereby losing the "benefit of time" (meaning the full outstanding loan became immediately due). B Public Corporation's claim, including principal and interest, amounted to over 7.14 million yen. Prior to these defaults, on June 26, 1959, A Co. had already filed a petition for the commencement of corporate reorganization proceedings.

On December 25, 1959, the court formally commenced corporate reorganization proceedings for A Co., and Y and others were appointed as A Co.'s reorganization trustees. Subsequently, on January 30, 1960, B Public Corporation assigned all its claims against A Co., along with the associated mortgage rights and the jōto tanpo rights over the machinery, to X Bank.

On March 10, 1960, X Bank filed a proof of claim in A Co.'s reorganization proceedings, asserting its status as a "reorganization secured creditor" (更生担保権者 - kōsei tanpo kensha). In its filing, X Bank specifically mentioned both the mortgage on the real estate and the jōto tanpo over the machinery as the bases for its secured claim. A Co.'s reorganization trustees (Y et al.) acknowledged and treated X Bank's claim as a reorganization secured claim. During the formal claim investigation process, X Bank's entire claim was recognized as a valid reorganization secured claim.

A reorganization plan for A Co. was eventually approved by the court on December 19, 1960. This plan stipulated that the mortgage held by X Bank over A Co.'s land and factory would continue to exist until the full amount of X Bank's secured debt was repaid in installments according to the plan. However, the approved reorganization plan did not recognize the continuation of X Bank's jōto tanpo over the machinery as a distinct ownership right that would allow X Bank to reclaim the machinery.

Dissatisfied with this aspect of the plan, X Bank then initiated a separate lawsuit against the reorganization trustees (Y et al.). In this new lawsuit, X Bank asserted that it held outright ownership of the factory machinery based on the jōto tanpo agreement and demanded the physical return of these assets by exercising a right of reclamation.

The Kyoto District Court (Maizuru Branch), at first instance, dismissed X Bank's claim. It reasoned that since X Bank had participated in the corporate reorganization proceedings as a secured creditor and a reorganization plan had been duly approved, X Bank was bound by the terms of that plan. The court found that X Bank's rights as a secured creditor were sufficiently protected by the continuation of its mortgage under the plan, and therefore, the jōto tanpo over the machinery should be considered extinguished or superseded by the plan.

The Osaka High Court, on appeal by X Bank, also dismissed the claim, but its reasoning differed. The High Court acknowledged the general legal principle that a jōto tanpo arrangement could, in some circumstances, confer upon the creditor a right of reclamation exercisable outside of reorganization proceedings. However, it also stated that even such rights must be exercised in accordance with the principle of good faith and could be subject to restrictions if their exercise constituted an abuse of rights. Critically, the High Court held that if a jōto tanpo holder chooses to participate in corporate reorganization proceedings by filing their claim as a secured creditor, and if their jōto tanpo right is not specifically recognized as a continuing right under the terms of the approved reorganization plan, then that right is effectively extinguished by operation of law upon the plan's confirmation (citing Article 241 of the old Corporate Reorganization Act, which detailed the effects of plan confirmation, including the modification or discharge of debts and security interests).

X Bank appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that: (1) having once acquired legal ownership of the machinery via the jōto tanpo agreement, it possessed an inherent right of reclamation under Article 62 of the old Corporate Reorganization Act (which dealt with rights of reclamation); (2) jōto tanpo was not explicitly listed in Article 123 of the old Act (which defined "reorganization secured claims"), and therefore, a debt secured by jōto tanpo should not be treated as a reorganization secured claim subject to the plan; (3) X Bank had not intended to file its claim specifically as a jōto tanpo-based reorganization secured claim in a way that would waive its ownership rights; and (4) even if it had been filed as such, jōto tanpo could not simply be treated in the same manner as statutory security interests like mortgages or pledges due to its nature as a transfer of title.

The Legal Issue: Status of a Jōto Tanpo Holder in Corporate Reorganization – Outright Owner with Reclamation Rights, or a Secured Creditor Subject to the Plan?

The core legal issue before the Supreme Court was the fundamental status of a creditor holding jōto tanpo when the debtor company enters corporate reorganization proceedings before the jōto tanpo has been definitively foreclosed or realized (i.e., while the underlying debt relationship still exists and the transfer of title remains primarily for security purposes).

- The "Title Theory" (所有権的構成 - shoyūkenteki kōsei) perspective: This view emphasizes the formal transfer of legal title to the creditor. If the creditor is considered the legal owner, they should logically have a right to reclaim "their" property from the reorganizing company's estate, independent of the reorganization plan, much like the owner of leased equipment could reclaim it.

- The "Security Interest Theory" (担保的構成 - tanpoteki kōsei) perspective: This view focuses on the economic substance of jōto tanpo as primarily a security device, despite the formal transfer of title. If it is substantively a security interest, then the holder should be treated similarly to other secured creditors (like mortgagees or pledgees) within the collective framework of corporate reorganization, meaning their rights would be subject to the reorganization plan and they would not have an automatic right to reclaim the collateral if it is essential for the debtor's business rehabilitation.

Corporate reorganization proceedings aim to rehabilitate a financially distressed company, which often requires adjusting the rights of all creditors, including secured creditors, and typically involves keeping the company's essential business assets intact for continued operation. Allowing a jōto tanpo holder to reclaim key operational assets like factory machinery could severely undermine this rehabilitative goal.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Right of Reclamation; Treated Analogously to a Reorganization Secured Creditor

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of April 28, 1966, dismissed X Bank's appeal. It held that, under the circumstances presented, X Bank did not have a right of reclamation over the machinery and should instead exercise its rights within the framework of the corporate reorganization proceedings, analogous to other reorganization secured creditors.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Non-Absolute (Non-Final) Transfer of Ownership: The Court found that at the time A Co.'s corporate reorganization proceedings commenced (December 25, 1959), the transfer of ownership of the subject machinery to X Bank (as successor to B Public Corporation) under the jōto tanpo agreement was not absolute or final (確定的 - kakuteiteki). This was because the underlying debtor-creditor relationship regarding the loan still persisted between A Co. and X Bank; the debt had not been extinguished, and the title transfer remained for security purposes.

- Treatment Analogous to a Reorganization Secured Creditor: The Court stated that in such a situation—where the transfer of ownership under a jōto tanpo arrangement is not yet absolute or final, and the underlying debtor-creditor relationship continues to exist—the holder of the jōto tanpo (X Bank) should be treated analogously to a "reorganization secured creditor" (更生担保権者に準じて - kōsei tanpo kensha ni junjite).

- Requirement to Participate in Reorganization Proceedings: This means that the jōto tanpo holder must file a proof of their secured claim in the corporate reorganization proceedings and seek satisfaction of their claim through the mechanisms provided by the Corporate Reorganization Act and according to the terms of an approved reorganization plan.

- No Right to Reclaim Collateral Based on Ownership: Crucially, the Court concluded that the jōto tanpo holder cannot assert their formal legal title to the collateral as a basis to demand its physical return from the reorganizing company's estate (i.e., they cannot exercise a right of reclamation).

Significance of the Judgment: Settling a Key Debate on Jōto Tanpo in Reorganization

This 1966 Supreme Court decision was a landmark ruling because it was the first time Japan's highest court directly addressed the status of jōto tanpo holders in corporate reorganization proceedings.

- Endorsement of a Substance-Over-Form / Security Interest View in Reorganization: The decision effectively adopted a "security interest theory" approach, or at least a substance-over-form analysis, for the treatment of jōto tanpo within the specific context of corporate reorganization. It prioritized the overriding goals of the reorganization process—business rehabilitation and equitable adjustment of all stakeholder rights—over a purely formalistic interpretation of the jōto tanpo as an outright transfer of ownership that would allow reclamation. By requiring jōto tanpo holders to participate in the plan like other secured creditors, the Court aimed to ensure that essential business assets covered by such security could remain with the reorganizing company if necessary for its turnaround, subject to adequate protection or satisfaction being provided to the secured creditor under the plan.

- Impact on Legal Practice: Following this judgment, it became the established practice in Japanese corporate reorganization proceedings to treat jōto tanpo holders as reorganization secured creditors who must file claims and have their rights dealt with under the reorganization plan, rather than as outright owners with an immediate right to reclaim the collateral, provided that the jōto tanpo had not been definitively "foreclosed" or otherwise realized (and the debt relationship extinguished) before the commencement of the reorganization proceedings.

- When Reclamation Might Still Be Possible: The judgment's reasoning, focusing on the "non-absolute" nature of the title transfer and the persistence of the debtor-creditor relationship, implies that if the jōto tanpo security interest had been fully and finally executed prior to the commencement of reorganization proceedings—for example, if a formal settlement process (seisan) had occurred where title became definitively vested in the creditor and the underlying debt relationship was extinguished—then the creditor might indeed have been able to assert a right of reclamation as the true and unencumbered owner of the asset. The key distinction lies in whether the jōto tanpo was still serving its security function for an ongoing debt at the time reorganization began.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1966 decision was a pivotal development in Japanese insolvency law, particularly concerning the treatment of jōto tanpo, a widely used but non-statutory form of security. By ruling that jōto tanpo holders whose security has not yet been definitively realized must generally participate in corporate reorganization proceedings as secured creditors rather than exercising a right of reclamation based on formal title, the Court effectively integrated this unique security device into the collective framework of corporate rehabilitation. This approach reflects a balancing of interests, acknowledging the secured creditor's rights while upholding the broader public policy objectives of preserving viable businesses and ensuring a structured, equitable adjustment of all claims in a corporate reorganization. The decision brought much-needed clarity to a long-debated issue and has had a lasting influence on insolvency practice in Japan.