Securing the Unsecured: When Can a Supplier Claim a Contractor's Receivables in Japan?

Date of Decision: December 18, 1998

Case Name: Appeal with Permission against Decision Dismissing an Execution Appeal against an Order for Attachment and Assignment of Claim

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

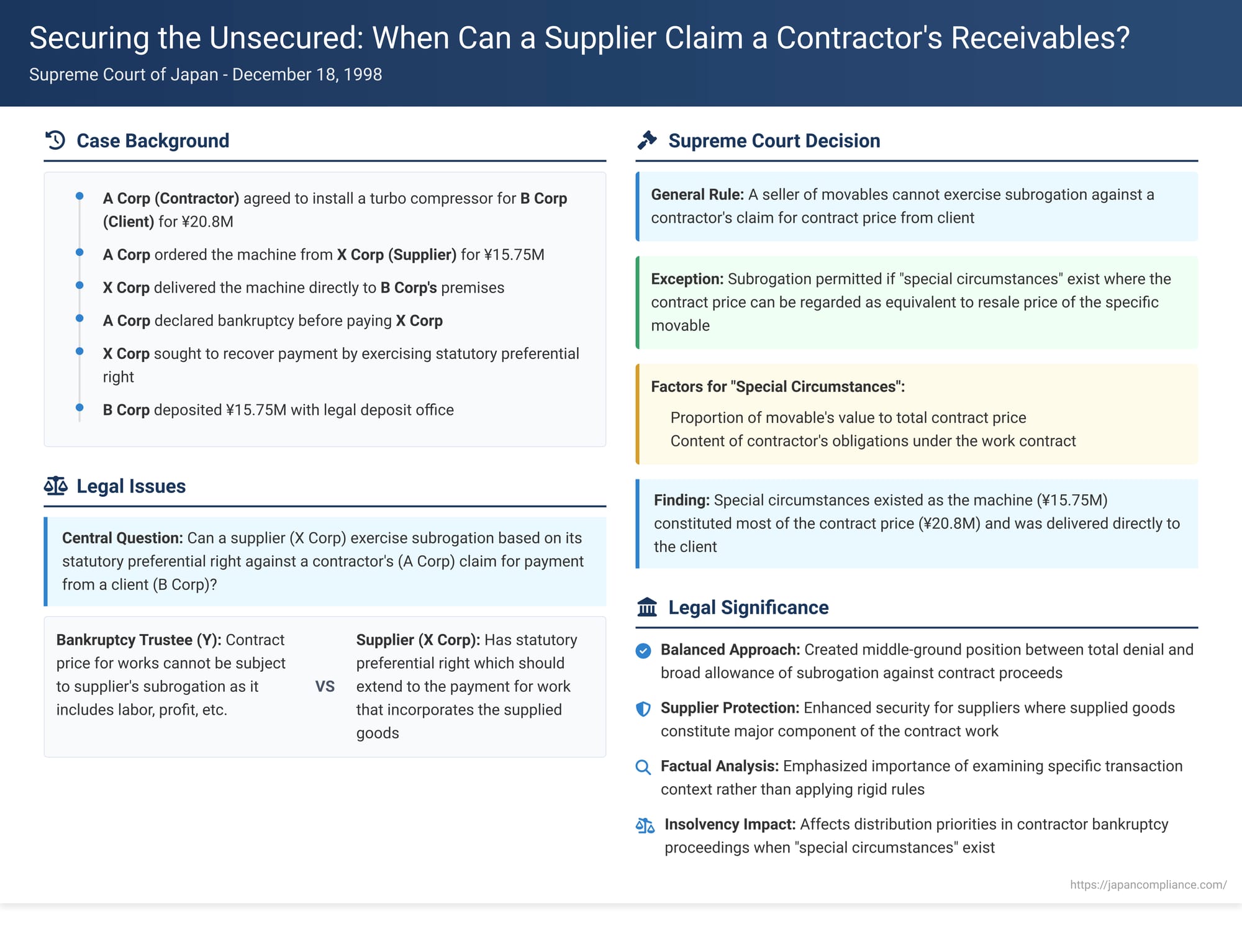

In the complex web of commerce, suppliers of goods often face the risk of non-payment, especially when their buyer, who may be a contractor, faces insolvency. Japanese law provides certain creditors with "statutory preferential rights" (sakidori tokken), which can offer a path to recovery outside or alongside conventional security interests. One feature of these rights is the potential for "subrogation over property" (butsujō daii), allowing the creditor to pursue the proceeds or substitutes for the object over which their preferential right exists. A key Supreme Court decision on December 18, 1998, addressed a critical question: Can a supplier of machinery exercise this right of subrogation against the payment owed to their buyer (a contractor) by a third-party client for whom the contractor performed installation work using that machinery? The Court carved out a narrow exception to a general rule of denial.

The Commercial Setting: A Chain of Contracts and a Bankruptcy

The case involved a series of interconnected commercial transactions that were disrupted by an insolvency:

- A Corp., a contractor, entered into an agreement with B Corp. to install a turbo compressor (referred to as the "Machine") for B Corp. The total contract price for this installation work was ¥20.8 million.

- To execute this project, A Corp. ordered the necessary Machine from a supplier, X Corp., for a price of ¥15.75 million.

- Under A Corp.'s instructions, X Corp. delivered the Machine directly to B Corp.'s premises.

- Subsequently, A Corp. was declared bankrupt.

- X Corp., as the unpaid seller of the Machine, sought to recover the outstanding amount. X Corp. asserted its statutory preferential right for the sale of movables (dōsan baibai sakidori tokken) over the Machine. Since the Machine was now in B Corp.'s possession and integrated into the project, X Corp. aimed to exercise its right of subrogation over A Corp.'s claim against B Corp. for the installation contract price.

- X Corp. initially obtained a provisional attachment order for ¥15.75 million against A Corp.'s claim on B Corp. In response, B Corp. deposited this amount (¥15.75 million) with a legal deposit office (kyōtaku).

- Following this, X Corp. successfully obtained an order from the court to attach and have assigned to itself (sashiosae meirei oyobi tempu meirei) the right of A Corp.'s bankruptcy trustee (Y Trustee) to claim a refund of this deposited money (kyōtakukin kampu seikyūken).

- Y Trustee, representing A Corp.'s bankrupt estate, objected to this attachment and assignment order, but the objection was dismissed by the lower court. The lower court then granted Y Trustee permission to appeal this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: Subrogation Against a Contract Price

The central legal issue before the Supreme Court was whether X Corp., the seller of the Machine, could legitimately exercise its statutory preferential right by way of subrogation against A Corp.'s claim for payment from B Corp. This claim was for the price of contract work (ukeoi daikin saiken), not a simple resale of the Machine.

This question is challenging because a contract price for works typically includes various components beyond the mere cost of one specific piece of equipment. It often covers labor, other materials, overheads, and profit. It is not immediately obvious that such a composite claim can be considered the "proceeds" or "substitute" for a specific movable in the way that the direct sale price of that movable would be.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 18, 1998): A Principled Exception

The Supreme Court, in its decision, dismissed Y Trustee's appeal, ultimately permitting X Corp.'s subrogation in this particular instance, but it did so by establishing a general rule of denial with a carefully defined exception.

- General Rule – No Subrogation Against Contract Price for Works: The Court began by stating that a claim for payment obtained by the buyer of a movable for performing contract work using that movable encompasses consideration for all materials, labor, and other elements involved in completing the work. Therefore, it cannot be automatically assumed that any specific part of such a claim corresponds to the resale price of the particular movable. Consequently, the Court established that, as a general principle, the seller of a movable used in contract work cannot exercise a right of subrogation based on their statutory preferential right for the sale of movables against the contractor's claim for the contract price from the client.

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception: Despite this general prohibition, the Court carved out an exception. It held that subrogation can be permitted if "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) exist, under which the whole or a part of the contract price claim can be "regarded as equivalent" (dōshi suru ni tariru) to a claim for the resale price of that specific movable.

- Key Factors for the Exception: The Court identified two primary considerations for determining if such "special circumstances" exist:

- The proportion of the value of the specific movable in question to the total contract price for the works.

- The content of the contractor's obligations under the contract for work (i.e., what the contractor was actually required to do with the movable).

- Application to the Facts of This Case: The Supreme Court found that such "special circumstances" were present in this specific case:

- A Corp. had contracted with B Corp. for the installation of the Machine for a total price of ¥20.8 million. A Corp. had purchased this specific Machine from X Corp. for ¥15.75 million.

- Crucially, X Corp. delivered the Machine directly to B Corp. based on A Corp.'s instructions.

- Furthermore, the quotation submitted for the installation project clearly indicated that ¥17.4 million of the ¥20.8 million total contract price was attributable to the price of the Machine itself.

- Given these facts—particularly the high proportion of the Machine's cost within the total project price and the direct delivery from X Corp. to B Corp. (implying minimal transformation or value added to the Machine itself by A Corp.)—the Court concluded that there were indeed "special circumstances" to regard A Corp.'s claim against B Corp. (at least up to the value of the machine) as equivalent to a resale price claim for the Machine that X Corp. had sold to A Corp.

- Therefore, the deposited funds of ¥15.75 million (which represented a significant portion of the Machine's value component within the contract price) were subject to X Corp.'s statutory preferential right through subrogation. The lower court's decision allowing the attachment and assignment was thus upheld as correct. The Supreme Court also noted that this conclusion did not conflict with an older precedent from the Great Court of Cassation (Taishō 2, 1913).

Understanding Statutory Preferential Rights and Subrogation in Japan

To fully grasp the decision, it's helpful to understand two key concepts:

- Sakidori Tokken (Statutory Preferential Rights): These are rights created by the Civil Code and other statutes that give certain types of creditors a priority claim over specific property of their debtors, or over the general property of their debtors, for the satisfaction of their claims. The preferential right for the sale of movables, asserted by X Corp., is one such right, intended to secure the seller for the price of goods sold. These rights arise automatically by law when the conditions are met and do not generally require registration or agreement, though their efficacy against third parties can vary.

- Butsujō Daii (Subrogation over Property): Article 304 of the Civil Code provides that a preferential right may also be exercised against money or other things that the debtor is to receive as a result of the sale, lease, loss of, or damage to the object of the preferential right. This is the right of subrogation. For it to be effective, the holder of the preferential right must attach (seize) these proceeds before they are paid or delivered to the debtor. X Corp.'s action was an attempt to use this mechanism.

The Evolution of Legal Thinking on This Issue

The question of whether a supplier's preferential right can extend to a contractor's receivables has been a subject of debate:

- Historical Denial: An early Great Court of Cassation decision in 1913 denied subrogation for a timber supplier against a contract price for arsenal construction, reasoning that the contract price covered all labor and materials and didn't solely represent the timber. Some later lower court decisions and scholars adopted this restrictive view.

- Affirmative Academic View: The majority of legal scholars, however, leaned towards permitting such subrogation. They argued on grounds of fairness (the contract price substantively includes the material costs) and the practical utility of subrogation (it should cover value equivalents, not just direct proceeds, otherwise its purpose is diminished).

- The 1998 Supreme Court's "Eclectic" Approach: This Supreme Court decision positions itself as a compromise or "eclectic" view. It acknowledges the general difficulty in equating a contract price for works with a simple resale price but allows for an exception under tightly defined "special circumstances". In doing so, it considers both the value proportion of the movable and the nature of the contractor's work involving that movable.

Why "Special Circumstances" Mattered Here

The Supreme Court's emphasis on "special circumstances" was pivotal. In this case:

- High Price Proportion: The cost of the Machine (¥15.75 million purchase price, ¥17.4 million component in contract price) constituted a very large part of the total ¥20.8 million contract price. This made it easier to identify a significant portion of the receivable as being directly attributable to the Machine.

- Direct Delivery & Minimal Transformation by Contractor: The Machine was delivered directly from the supplier (X Corp.) to the end-user (B Corp.). This meant that A Corp.'s role concerning the Machine itself was largely that of an intermediary for supply and installation, rather than a party that significantly transformed or incorporated the Machine into a much larger, more complex product through its own extensive labor or by adding many other materials. This "content of the contractor's obligations" made the portion of B Corp.'s payment related to the Machine closely resemble a payment for the Machine itself.

This contrasts with scenarios where supplied materials are heavily processed, lose their identity, or form a minor, indistinguishable component of a complex finished work. In such cases, identifying a specific portion of the contract price as equivalent to the "resale price" of the original materials would be much more difficult, if not impossible.

Implications for Suppliers and Contractors

The 1998 Supreme Court decision provides important, albeit nuanced, guidance:

- For Suppliers: It confirms that while subrogation against a contractor's general receivables for works is generally not allowed, there is a potential avenue for recovery if the supplied goods represent a dominant and identifiable portion of the contract value, and if the contractor’s role involves minimal alteration or incorporation of those specific goods. Suppliers in such situations may have a stronger basis to assert their preferential rights over proceeds. Careful documentation of the value of supplied goods within overall project costs will be crucial.

- For Contractors (and their Insolvency Administrators): This decision clarifies that certain receivables, previously thought to be general assets of the contractor's estate, might be subject to the preferential rights of specific suppliers under these "special circumstances." This could affect the distribution of assets in insolvency proceedings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of December 18, 1998, offers a carefully balanced approach to a complex issue at the intersection of contract law, insolvency, and statutory security rights. By generally denying subrogation for sellers of movables against a contractor's receivables for works, but allowing for a tightly defined exception based on "special circumstances" where the contract price is clearly equivalent to the resale price of the supplied goods, the Court sought to protect suppliers in limited, identifiable situations without unduly disrupting the general principles governing contract receivables. This ruling underscores the importance of specific factual contexts in the application of broad legal principles and provides a framework for assessing the reach of statutory preferential rights in chained commercial transactions.