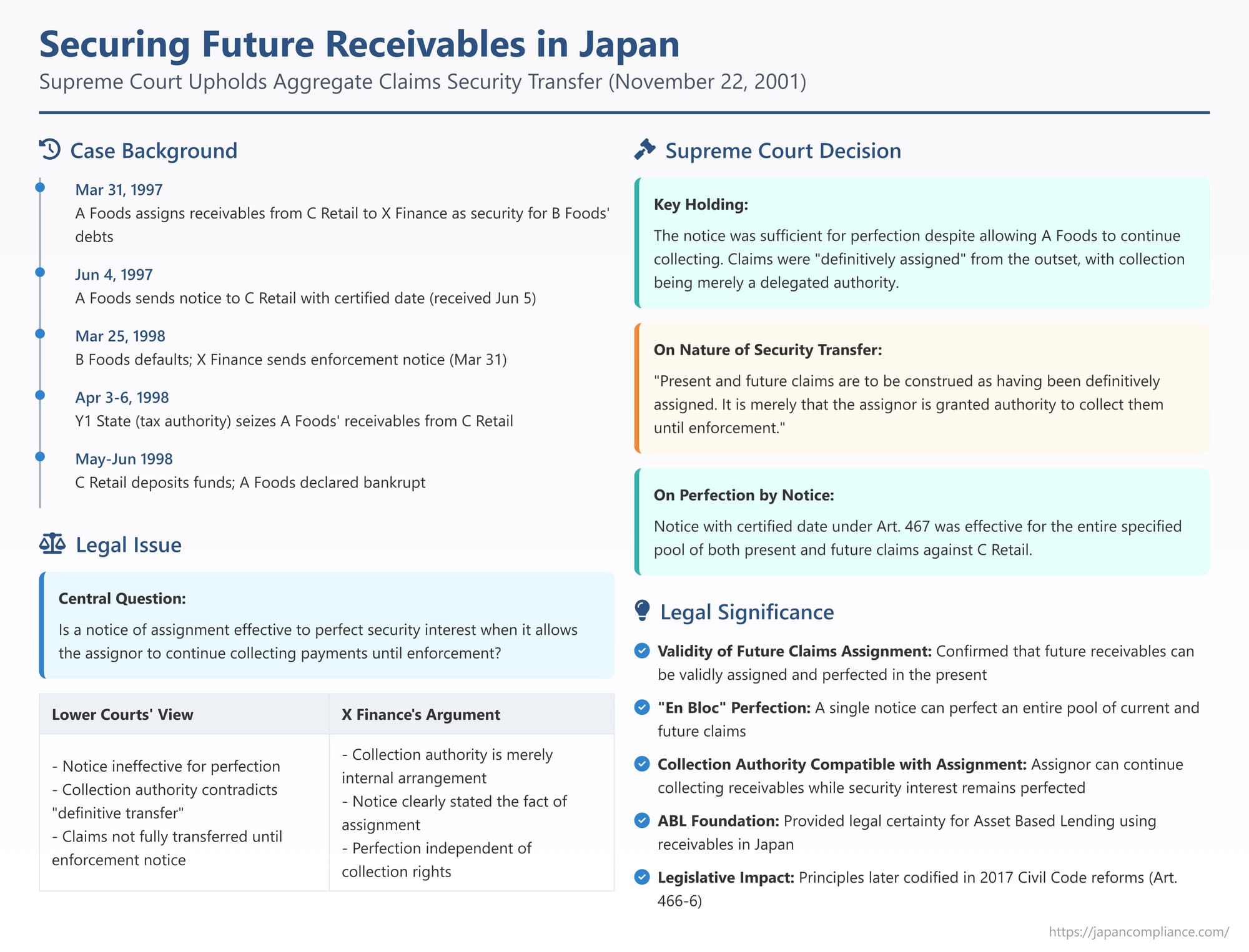

Securing Future Receivables in Japan: Supreme Court Upholds Aggregate Claims Security Transfer

Date of Judgment: November 22, 2001

Case Name: Action for Confirmation of Right to Claim Refund of Deposited Money

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

For many businesses, their accounts receivable represent a significant asset. The ability to use these receivables – both current and future – as collateral for financing is crucial for cash flow and growth. In Japan, a common mechanism for this is the "aggregate claims security transfer" (shūgō saiken jōto tanpo), where a business assigns a pool of its present and future receivables to a lender as security. A key legal question has been how such a security interest, especially over future claims, can be effectively perfected against third parties, particularly when the assigning business continues to collect the receivables in its ordinary operations. The Supreme Court of Japan provided a landmark clarification on this issue in a judgment on November 22, 2001.

The Transaction: Securing Debts with a Pool of Present and Future Receivables

The case involved X Finance, a lender; A Foods, a company that assigned its receivables; B Foods, the primary debtor whose obligations to X Finance were being secured; and C Retail, a major customer of A Foods whose payments were the subject of the assignment.

- The Security Assignment Agreement: On March 31, 1997, A Foods entered into a "security assignment of claims agreement" with X Finance.

- Purpose: This agreement was designed to secure all present and future debts that B Foods owed to X Finance. A Foods was effectively providing third-party security.

- Subject Matter (The Target Claims): A Foods assigned to X Finance all its present accounts receivable for product sales and sales consignment commissions against C Retail arising from their ongoing business relationship, as well as all such claims that would arise within one year from that date (i.e., until March 31, 1998). This created a security interest over a fluctuating pool of A Foods' receivables from C Retail.

- Collection Arrangement: A crucial term of the agreement was that A Foods was permitted to continue collecting payments on these Target Claims directly from C Retail for its own account. A Foods was not required to remit these collected funds to X Finance unless and until X Finance formally notified C Retail that it was enforcing its security interest (which would typically happen upon an event of default by the primary debtor, B Foods).

- Notice to the Account Debtor (C Retail): On June 4, 1997, A Foods sent a formal notice to C Retail regarding this arrangement. The notice was sent by content-certified mail and bore a "certified date" (kakutei hizuke) – a notarial stamp that officially records the date of the document, crucial for establishing priority in Japanese law. C Retail received this notice on June 5, 1997. The notice contained two key statements:

- A Foods stated that it had created a security transfer right in favor of X Finance over the specified Target Claims that A Foods had (or would have) against C Retail, and that this notification was being made pursuant to Article 467 of the Civil Code (which governs the perfection of claim assignments).

- It further stated that if X Finance subsequently notified C Retail that it was enforcing its security interest, C Retail should thereafter make all payments of these claims directly to X Finance.

- Default and Enforcement by X Finance: On March 25, 1998, B Foods (the primary debtor) defaulted on its obligations to X Finance. This triggered the enforcement provisions of the security assignment agreement between A Foods and X Finance. Consequently, on March 31, 1998, X Finance sent a written notice to C Retail, informing C Retail that X Finance was now enforcing its security interest over the Target Claims. (This enforcement notice itself did not have a certified date).

- Intervening Tax Seizure: In the interim, on April 3 and April 6, 1998, Y1 State (representing the Japanese tax authorities) took action to collect A Foods' delinquent taxes. Y1 State sent attachment notices to C Retail, seizing specific accounts receivable and commission claims that A Foods had against C Retail for sales made between March 11 and March 30, 1998 (these were part of the broader pool of Target Claims assigned to X Finance).

- Deposit of Funds by C Retail and A Foods' Bankruptcy: Faced with competing claims from X Finance (asserting its security assignment) and Y1 State (asserting its tax lien), C Retail, on May 26, 1998, deposited the amount of the disputed claims with a legal deposit office. This deposit was made with A Foods or X Finance named as potential rightful payees, a common procedure when a debtor is unsure to whom payment should be made. Shortly thereafter, on June 25, 1998, A Foods was declared bankrupt, and Y2 Trustee was appointed to manage its estate.

- X Finance's Lawsuit: X Finance filed a lawsuit against Y1 State and Y2 Trustee (representing A Foods' bankrupt estate), claiming that it was the rightful creditor of the Disputed Claims by virtue of its perfected security assignment. X Finance sought a court confirmation of its entitlement to the funds deposited by C Retail. The central legal issue was whether the notice sent by A Foods to C Retail on June 4, 1997, was effective under Civil Code Article 467 to perfect the assignment of the Target Claims (including those that were still future claims at the time of the notice) to X Finance against third-party claimants like Y1 State.

The Lower Courts' Skepticism: Was the Notice of Assignment Effective?

Both the District Court and the High Court ruled against X Finance, finding the notice to C Retail insufficient to perfect the assignment.

- The District Court reasoned that the claims were effectively transferred to X Finance only when X Finance later issued its enforcement notice to C Retail. Therefore, the earlier June 1997 notice (of the assignment itself) could not perfect an assignment that, in its view, had not yet fully taken effect in terms of X Finance's right to collect.

- The High Court went further. It held that even if the claims were considered assigned to X Finance at the time of the initial Agreement in March 1997, the specific wording of the June 1997 notice was problematic. Because the notice explicitly allowed C Retail to continue paying A Foods until X Finance issued a separate enforcement notice, and implicitly allowed C Retail to continue asserting any set-off rights it might have against A Foods, the High Court concluded that the notice did not unequivocally inform C Retail that ownership of the claims had actually and definitively transferred to X Finance. Therefore, C Retail could not be expected to recognize a true change in the creditor for these claims based on that notice alone, rendering the notice ineffective for perfection against third parties.

X Finance appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the June 1997 notice clearly stated the fact of the security assignment, and the provision allowing A Foods to continue collecting was merely an internal arrangement between the assignor and assignee, which did not negate the perfection of the assignment itself.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Clarification (November 22, 2001)

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of X Finance, providing crucial clarifications on the nature and perfection of aggregate claims security transfers.

- Nature of Aggregate Claims Security Transfer with Collection Mandate to Assignor:

The Court first defined the type of transaction at issue: "An agreement between Party A and Party B, whereby A, to secure its monetary debts to B, assigns to B a block of presently existing or future claims that A has against Party C (specified by the type of transaction giving rise to them, the period of their accrual, etc.), while permitting A to collect the assigned claims and not requiring A to remit the collected funds to B until B notifies C of its intent to enforce the security as a secured party, is understood as one type of what is known as a security transfer agreement over an aggregate of claims."

The Court then clarified its legal construction: "In this case, the presently existing or future claims are to be construed as having been definitively assigned from A to B. It is merely that, between A and B, an agreement has been added whereby, concerning a part of the claims that have vested in B, A is granted the authority to collect them, and is not required to deliver the collected funds to B."

This means the assignee (X Finance) becomes the legal owner of the claims from the outset. The assignor's (A Foods') ability to continue collecting is a contractually delegated authority from the assignee, not an indication that the assignor retains ownership. - Sufficiency of the Notice for Perfection:

Based on this understanding, the Supreme Court held that such an assignment can be perfected against third parties (including the third-party debtor of the assigned claims) using the methods prescribed in Article 467, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code (i.e., a notice from the assignor to the third-party debtor, or the third-party debtor's consent, effected by a document bearing a certified date).

The Court directly addressed the problematic wording of the notice in this case:- The statement in the June 1997 notice that "A Foods has created a security transfer right for X Finance over the Target Claims... and notifies C Retail under Civil Code Article 467" was found to be "clearly stating that A Foods assigned the Target Claims to X Finance as security, and as a notice for perfecting the assignment of the Target Claims against third parties, it lacks nothing in its description."

- The additional statement that C Retail should pay X Finance only after X Finance issues a separate enforcement notice was construed as "X Finance, having had claims belonging to itself, granted collection authority to A Foods, and therefore, it should be understood as encompassing the intent of requesting C Retail to pay A Foods until a separate notice is given. It is improper to hold that, due to the existence of this statement, the notice cannot be recognized as a notification that the claims have been transferred to X Finance."

- Outcome: The Supreme Court concluded that the June 1997 notice effectively perfected X Finance's security assignment over the Target Claims (including the Disputed Claims which arose later but within the specified period) against third parties. Since this perfection occurred well before Y1 State's tax seizure in April 1998, X Finance's security interest had priority. X Finance was therefore declared to be the party entitled to the funds deposited by C Retail.

Key Principles of Aggregate Claims Security Transfers in Japan

This 2001 judgment by the Supreme Court reinforces several vital principles for using pools of receivables as security in Japan:

- Validity of Assigning Future Claims: The decision implicitly and explicitly supports the principle that future claims (receivables not yet in existence but expected to arise from an ongoing relationship or specified future transactions) can be validly assigned in the present. For such an assignment to be effective, the future claims must be specified with reasonable clarity (e.g., by identifying the debtor, the underlying contract or transaction type giving rise to the claims, and the period during which they will arise). This principle was later explicitly codified in Article 466-6 of the Civil Code as part of the 2017 reforms (effective 2020).

- Perfection by Notice for a Pool of Claims: A single notice from the assignor to the account debtor (the party who owes the receivables), provided it is made by a document with a certified date, can perfect the assignment of an entire specified pool of present and future claims against the account debtor and other third parties. This "en bloc" perfection is highly practical for fluctuating receivables.

- Assignor's Retention of Collection Rights is Permissible: It is legally permissible to structure a security assignment of receivables such that the assignor (the business generating the receivables) continues to collect payments from its customers in the ordinary course of business until an event of default occurs or the secured party decides to enforce its security. This "collection mandate" to the assignor does not negate the underlying assignment of the claims to the secured party, nor does it invalidate a notice of assignment that properly discloses both the assignment and this collection arrangement. This is crucial for businesses as it allows them to maintain their customer relationships and normal cash flow operations while still using their receivables as collateral.

"Rights-Transfer Theory" vs. "Security Right Theory"

The Supreme Court's approach in this case, by emphasizing that the claims are "definitively assigned" to the secured party from the outset, aligns with what is often termed the "rights-transfer theory" (kenri iten-teki kōsei) of security assignments of claims. Under this view, the secured party becomes the legal owner of the claims, and the assignor's right to collect is merely a delegated authority. This can be contrasted with a pure "security right theory" (tampoken-teki kōsei), where the assignor might be seen as retaining legal title to the claims but granting a security interest (akin to a pledge) over them to the secured party. While the ultimate economic function is similar, the precise legal construction can have different implications for certain issues. Japanese case law, particularly for security over claims, has tended to adopt reasoning consistent with the rights-transfer model.

Importance for Asset Based Lending (ABL)

This Supreme Court judgment provides very strong support for the legal framework underpinning Asset Based Lending (ABL) in Japan, especially where revolving lines of credit are secured by a company's fluctuating pool of accounts receivable. By affirming the validity of assigning future claims, the effectiveness of a single notice for perfecting rights over an entire pool, and the permissibility of allowing the assignor to continue collections, the Court has provided essential legal certainty for these types of financing arrangements. This allows lenders to confidently rely on receivables as collateral, thereby facilitating greater access to credit for businesses.

Legislative Developments

Many of the principles regarding the assignment of future claims and their perfection, which were established or affirmed through judicial precedents like this 2001 Supreme Court judgment and an earlier key case on future claims assignment (Supreme Court, January 29, 1999, Minshū Vol. 53, No. 1, p. 151 – the "M22 case"), were subsequently codified into the Japanese Civil Code as part of the major reforms to the law of obligations in 2017 (effective April 2020). For instance, Civil Code Article 466-6 now explicitly governs the assignment of future claims, and Article 467, Paragraph 1 confirms that perfection requirements can be met for future claims at the time of assignment.

Furthermore, discussions regarding more comprehensive legislative reforms for security interests over movables and claims have been ongoing in Japan, aiming to further modernize and clarify the legal framework for ABL and other forms of secured financing.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of November 22, 2001, was a vital decision that significantly bolstered the legal foundation for using aggregate claims (receivables pools) as security in Japan. By clearly ruling that a notice of assignment to the account debtor is effective for perfection even if it discloses that the assignor will continue to collect payments until the secured party enforces its rights, the Court provided crucial legal certainty and practicality for receivables financing. This endorsement of a flexible yet secure method of collateralizing present and future claims has been instrumental in supporting Asset Based Lending and facilitating business finance in Japan.