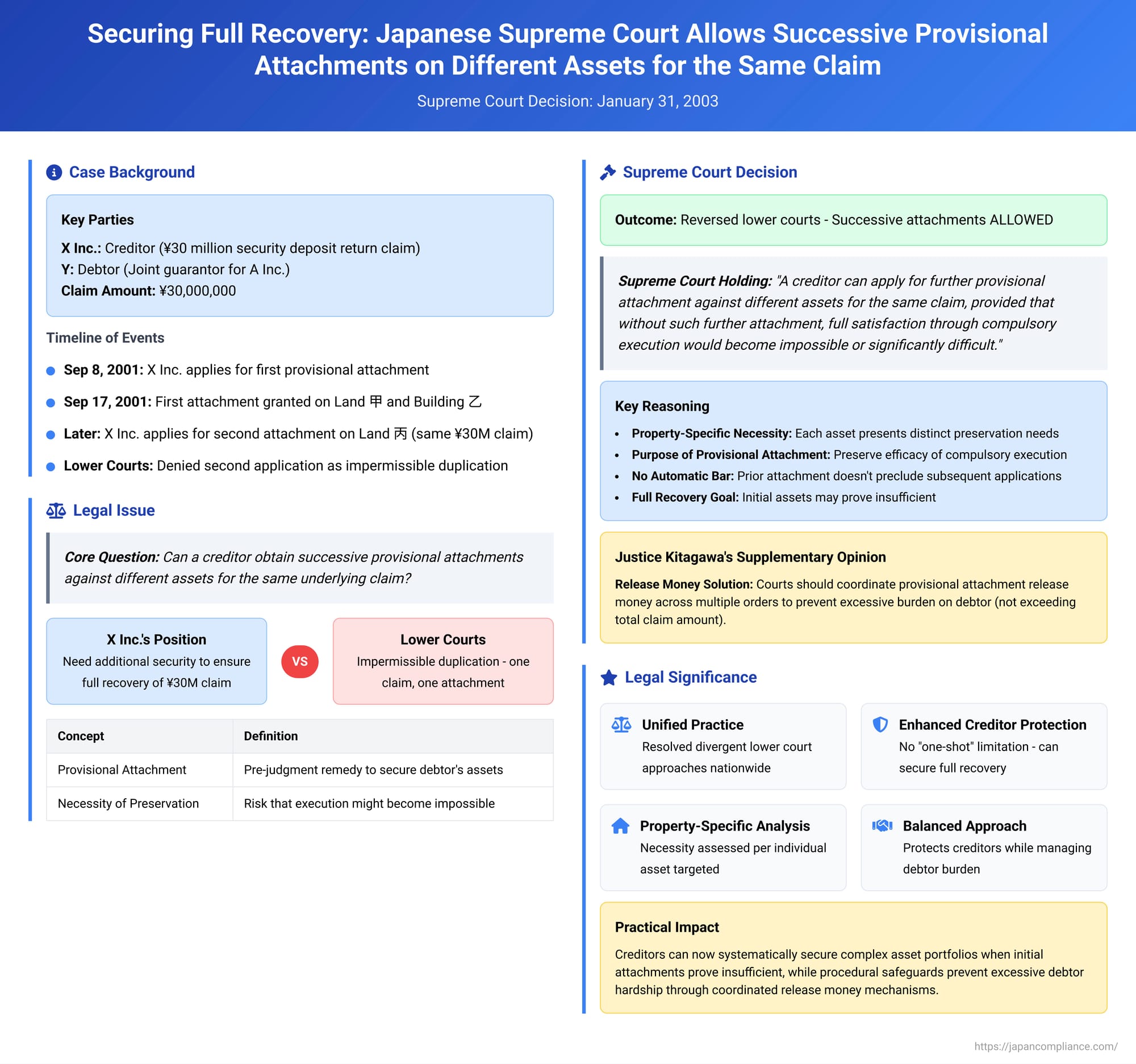

Securing Full Recovery: Japanese Supreme Court Allows Successive Provisional Attachments on Different Assets for the Same Claim

Date of Supreme Court Decision: January 31, 2003

In the often uncertain landscape of debt recovery, "provisional attachment" (仮差押え - karisashiosae) stands as a vital pre-judgment (or pre-full-enforcement) remedy in Japan. It allows a creditor to secure a debtor's assets to prevent their disposal, thereby preserving the possibility of satisfying a monetary claim once a final judgment is obtained or an existing enforceable title is acted upon. A key question that had divided lower courts was whether a creditor, having already secured one provisional attachment order against certain assets of a debtor, could legitimately apply for another provisional attachment order against different assets of the same debtor, all to secure the same underlying claim. On January 31, 2003, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Heisei 14 (Kyo) No. 23) provided a definitive and affirmative answer, emphasizing a nuanced understanding of the "necessity of preservation."

The Factual Scenario: Seeking Additional Security

The case involved X Inc. (the creditor) and Y (the debtor). The background was as follows:

- The Underlying Debt: X Inc. was the beneficiary of a ¥30 million security deposit return claim, originally owed by A Inc. upon the termination of a building lease. Y had acted as a joint and several guarantor for A Inc.'s obligation to return this security deposit.

- First Provisional Attachment: On September 8, 2001, X Inc., citing its ¥30 million claim against Y under the guarantee, applied for and, on September 17, 2001, obtained a provisional attachment order. This initial order targeted specific assets owned by Y: a parcel of land referred to as "Land 甲" and a building known as "Building 乙." This order was duly executed.

- The Second Application for Provisional Attachment: Subsequently, X Inc. filed another application for a provisional attachment order. This second application was for the exact same ¥30 million guarantee claim against Y. However, it targeted a different asset also owned by Y: another parcel of land referred to as "Land 丙."

The lower courts took a restrictive view. The Saga District Court (court of first instance) dismissed X Inc.'s second application, reasoning that it was impermissible to seek a duplicate provisional attachment order for a right that was already the subject of an existing preservation order. The Fukuoka High Court, on appeal, upheld this dismissal. These courts essentially found that X Inc. had already had its "bite at the apple" and that a second application for the same claim lacked the necessary legal justification, potentially on grounds akin to a broad interpretation of res judicata or a lack of the "right to protection of rights."

The Supreme Court's Reversal: A Nuanced View of "Necessity of Preservation"

The Supreme Court decisively reversed the lower courts' decisions and remanded the case to the Saga District Court for further consideration, effectively permitting the possibility of successive provisional attachments under certain conditions.

Core Holding: The Supreme Court ruled that a creditor who has already obtained a provisional attachment order against specific assets can apply for a further provisional attachment order against different assets for the same underlying claim, provided that, without such further attachment, there is an apprehension that full satisfaction of the monetary claim through compulsory execution would become impossible or significantly difficult.

Deconstructing the Supreme Court's Reasoning:

- Purpose of Provisional Attachment: The Court began by reiterating the fundamental purpose of provisional attachment as defined in the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA Articles 1 and 20, Paragraph 1). It is a system designed to preserve the efficacy of compulsory execution for a monetary claim when there is a risk that such execution might later become impossible or be met with significant difficulty (e.g., due to the debtor hiding or dissipating assets).

- Subject of Judicial Inquiry in Provisional Attachment: When a court considers an application for provisional attachment, its inquiry focuses on two main elements (CPRA Articles 13, 20, and 21):

- The existence and nature of the monetary claim to be preserved (the 被保全債権 - hihozen saiken).

- The "necessity of preservation" (保全の必要性 - hozen no hitsuyōsei) for that claim, specifically in relation to the particular property of the debtor targeted by the application. The CPRA (in Article 21) explicitly links provisional attachment orders for real property to specific assets, marking a departure from older legal theories that sometimes viewed such orders more abstractly.

- "Necessity" is Property-Specific: This focus on specific property led to the Court's crucial insight: even if a provisional attachment order has already been issued for a particular claim against certain assets (e.g., Land 甲 and Building 乙), a different and distinct necessity for provisional attachment may still exist if the creditor cannot obtain full satisfaction of that claim without also preserving execution against other, different assets (e.g., Land 丙). The necessity to attach Land 丙 to cover a potential shortfall is not the same necessity that justified attaching Land 甲 and Building 乙.

- No Automatic Bar to Successive Applications: Consequently, an application for provisional attachment against different assets (even for the same underlying claim) does not inherently lack the "requirements for protection of rights" (権利保護の要件 - kenri hogo no yōken). Because the "necessity" being assessed pertains to different property, the second application is not merely a repetitive plea that would be barred by principles analogous to res judicata (the rule against re-litigating the same matter).

- Conditions for Permitting Further Attachments: The key condition is whether, even considering the existing provisional attachment(s), there remains a demonstrable risk that the creditor will be unable to achieve full satisfaction of their claim unless the additional, different property is also provisionally attached. This could arise, for example, if the initially attached assets are insufficient in value, depreciate, or become subject to claims from other creditors.

Addressing Concerns about Successive Attachments: The Supreme Court also proactively addressed potential objections to allowing such successive applications:

- It would not lead to courts making "useless" or "redundant" judgments, as each application involves assessing the necessity concerning a new, distinct asset.

- It would not result in the creditor receiving "excessive satisfaction," as the ultimate recovery in the main proceedings is always limited to the actual amount of the debt. Provisional attachments are merely a means of security.

- The issue of provisional attachment release money (仮差押解放金 - karisashiosae kaihōkin – an amount the debtor can deposit to lift the attachment) was a more significant practical concern. If multiple attachments are placed for the same claim, the total release money stipulated in the orders might exceed the actual claim amount, unfairly burdening the debtor. The Court acknowledged this but stated that it is possible to manage this issue through procedural means (elaborated in a supplementary opinion) and that this potential complication does not constitute a fundamental obstacle to issuing further provisional attachment orders against different assets when necessary.

Justice Kitagawa's Supplementary Opinion: Practical Solutions for Release Money

Justice Koji Kitagawa provided an important supplementary opinion, concurring with the majority but offering concrete procedural solutions to the problem of potentially excessive provisional attachment release money:

- Stipulation in Subsequent Orders: When a court issues a subsequent provisional attachment order for the same underlying claim against a different asset, and the cumulative release money specified in all orders would exceed the actual claim amount, the court should include a stipulation in the subsequent order. This stipulation should state that the deposit of the release money for the later order can also be satisfied by the deposit already made (or to be made) for the earlier provisional attachment order(s) related to the same underlying claim, up to the total amount of that claim.

- Debtor's Actions: This allows the debtor to deposit a single sum, not exceeding the total secured claim, with the deposit office, cross-referencing all relevant provisional attachment case numbers. By submitting copies of this consolidated deposit certificate to the respective execution courts that issued the various provisional attachment orders, the debtor can seek the suspension or cancellation of all related attachments.

- Rectifying Omissions: If a court, perhaps unaware of a prior attachment, issues a subsequent order without such a coordinating stipulation for the release money, the debtor can file a "preservation objection" (保全異議 - hozen igi) against one of the orders to have such a clause added by the court.

- Purpose: These measures ensure that while a creditor can secure their claim adequately by attaching multiple assets if necessary, the debtor is not forced to deposit more than the total amount of the claim to free all their provisionally attached properties.

Significance and Impact of the Ruling

This 2003 Supreme Court decision had a significant impact on civil provisional remedy practice in Japan:

- Unification of Lower Court Practice: It resolved a notable divergence in how lower courts handled successive provisional attachment applications. Some, like the Tokyo District Court's provisional remedies division, had been generally restrictive, while others, like Osaka's, had been more permissive. This ruling provided much-needed clarity and a unified national standard.

- Reinforcement of Property-Specific Necessity: The decision firmly aligns the assessment of the "necessity of preservation" with the specific assets targeted by the provisional attachment application. This reflects the approach of the current Civil Provisional Remedies Act, which (for real property) ties provisional attachment orders to identified properties, rather than issuing abstract "permission to attach."

- No "One-Shot" Limitation for Creditors: Creditors are not restricted to a single attempt at provisional attachment. If the initial assets attached prove insufficient to cover the claim (due to factors like lower-than-expected value, subsequent depreciation, the discovery of previously unknown assets, or the intervention of other creditors' claims against the initially attached property), the creditor can seek to attach additional assets.

- Balancing Creditor and Debtor Interests: The decision, particularly when read with Justice Kitagawa's supplementary opinion, strikes a crucial balance. It empowers creditors to take necessary steps to fully secure their legitimate claims by allowing for the attachment of multiple assets if individually insufficient. Simultaneously, it provides clear mechanisms to protect debtors from the undue hardship of having to deposit excessive amounts of release money that might far exceed the actual underlying debt.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's January 31, 2003, judgment is a landmark in Japanese provisional remedy law. It confirms that the pursuit of full security for a legitimate claim can justify successive provisional attachments against different assets, provided the necessity for each additional attachment is demonstrated. By focusing the "necessity" inquiry on the specific asset sought to be attached in light of any existing security, the Court allows for a flexible and realistic approach. Crucially, the guidance on managing provisional attachment release money ensures that this enhanced creditor protection does not translate into an unmanageable or unfair burden on the debtor. This decision significantly bolsters the practical effectiveness of provisional attachment as a means for creditors to safeguard their interests in a dynamic economic environment where a debtor's asset portfolio may be complex or its value uncertain.