Securing Floating Assets: Japan's Supreme Court on Security Interests in Inventory

Date of Judgment: November 10, 1987

Case Name: Action for Third-Party Objection

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

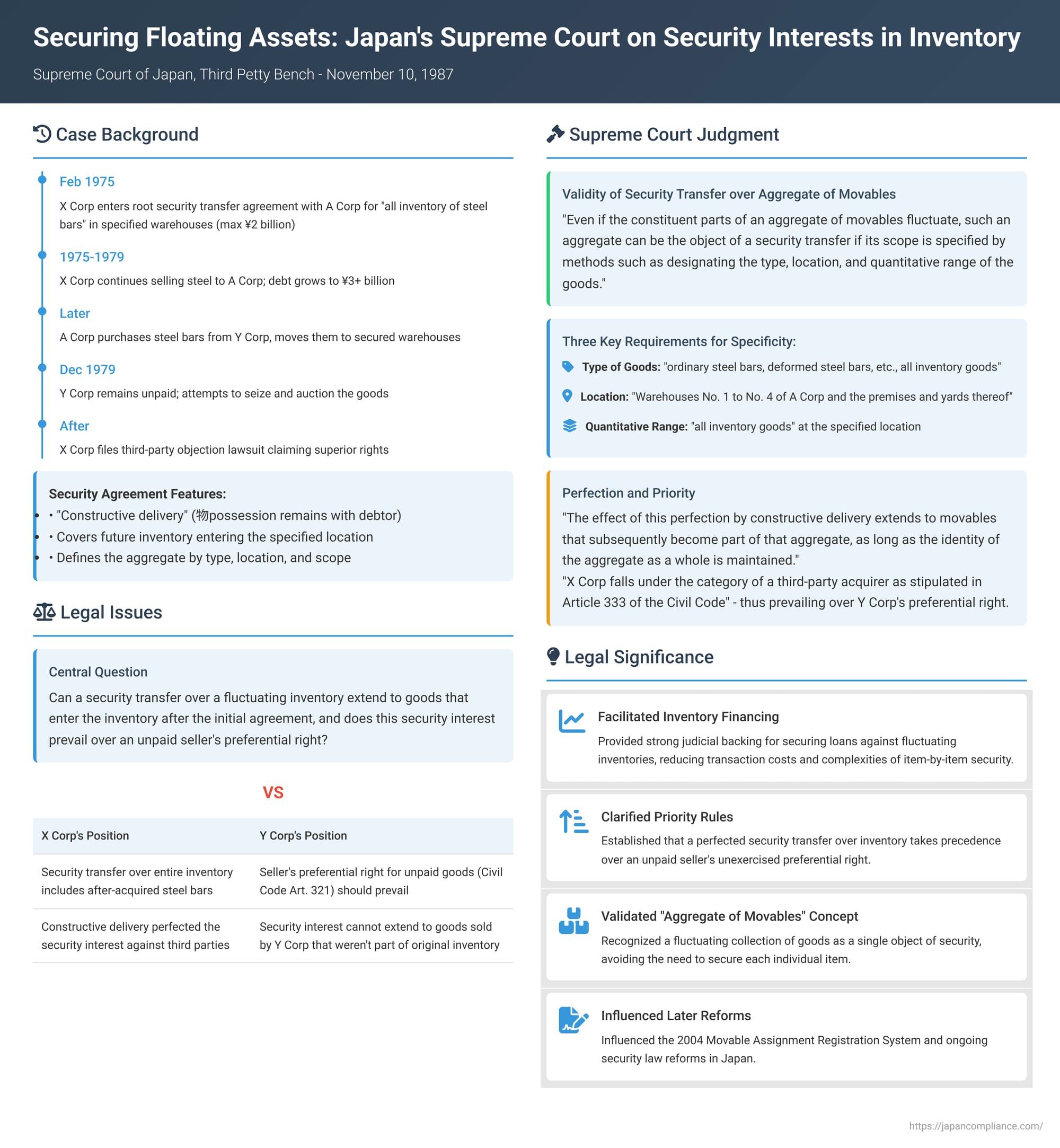

Creating effective security interests over assets that naturally fluctuate, such as a business's inventory, presents unique legal challenges. Traditional security mechanisms often focus on specific, identifiable items. However, for inventory financing, both lenders and borrowers need a practical way to secure a changing pool of goods. In Japan, the concept of a "security transfer" (jōto tanpo) over an "aggregate of movables" (shūgō dōsan) has evolved through case law to address this need. A landmark Supreme Court judgment on November 10, 1987, provided critical validation and clarification on the validity, perfection, and priority of such security interests in inventory.

The Business Scenario: Steel Inventory, a Security Agreement, and a Seller's Claim

The case involved a dispute between two major trading companies over steel inventory held by a third company that had sourced goods from both.

- X Corp.'s Root Security Transfer Agreement: On February 1, 1975, X Corp., a general trading company, entered into a comprehensive root security transfer agreement (ne-jōto tanpo ken settei keiyaku) with A Corp. (Debtor).

- Secured Debts: This agreement was designed to secure all present and future debts owed by A Corp. (Debtor) to X Corp., arising from various transactions such as product sales, promissory note obligations, damages, and advances, up to a maximum secured amount of ¥2 billion.

- Subject Matter of Security: A Corp. (Debtor) transferred ownership of "all inventory of ordinary steel bars, deformed steel bars, etc." that were currently located in its Warehouses No. 1 through No. 4, including the adjoining premises and yards (collectively, the "Specified Location").

- Perfection: Possession of this inventory was deemed delivered to X Corp. by way of "constructive delivery" (sen'yū kaitei), a method where the transferor (A Corp. (Debtor)) agrees to hold possession on behalf of the transferee (X Corp.), even though the goods remain physically with the transferor.

- After-Acquired Property Clause: The agreement stipulated that if A Corp. (Debtor) manufactured or acquired similar types of goods in the future, these goods were, in principle, to be brought into the Specified Location and would automatically become part of the security transfer to X Corp.

- Ongoing Business and Debt: X Corp. continued to sell steel products to A Corp. (Debtor). By November 30, 1979, A Corp. (Debtor)'s outstanding debt to X Corp. for these sales had grown to over ¥3 billion.

- Y Corp.'s Sale and A Corp. (Debtor)'s Inventory: Separately, A Corp. (Debtor) purchased a consignment of 8,529 deformed steel bars (the "Disputed Goods"), valued at approximately ¥5.85 million, from another trading company, Y Corp. A Corp. (Debtor) subsequently moved these Disputed Goods into the Specified Location (its warehouses), where they became part of its general inventory.

- Y Corp.'s Attempted Seizure: Y Corp. remained unpaid for the Disputed Goods. Claiming it held a "statutory preferential right for the sale of movables" (dōsan baibai sakidori tokken) under Article 321 of the Civil Code over these specific bars, Y Corp. initiated legal proceedings in December 1979 to have the Disputed Goods seized and sold at a compulsory auction (under the old Auction Act Article 3, now provided for in Civil Execution Act Article 190).

- X Corp.'s Objection: X Corp. intervened by filing a "third-party objection lawsuit" (daisansha igi no uttae) (a procedure under the old Code of Civil Procedure Article 549(1), now Civil Execution Act Article 38). X Corp. argued that its pre-existing, perfected security transfer over A Corp. (Debtor)'s entire inventory at the Specified Location gave it a superior right to the Disputed Goods, and therefore Y Corp.'s attempted auction should be blocked.

Lower Courts: Siding with the Security Transfer Holder

Both the District Court and the High Court ruled in favor of X Corp. They upheld the validity and priority of X Corp.'s security transfer interest over the entirety of A Corp. (Debtor)'s inventory at the Specified Location, including the subsequently added Disputed Goods. Y Corp. appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Judgment (November 10, 1987)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Corp.'s appeal, thereby affirming the decisions of the lower courts and providing crucial clarifications on the law governing security transfers of aggregates of movables.

I. Validity of Security Transfer over an Aggregate of Movables:

The Court first reiterated an established principle (citing its own precedent from February 15, 1979, Minshū Vol. 33, No. 1, p. 51): "[E]ven if the constituent parts of an aggregate of movables fluctuate, such an aggregate can be the object of a security transfer if its scope is specified by methods such as designating the type, location, and quantitative range of the goods." [cite: 1]

II. Perfection of Security Transfer over a Floating Stock and Its Effect on After-Acquired Goods:

The Court then elaborated on how such a security interest is perfected and how it applies to goods added later:

"And, when a security transfer agreement over such an aggregate as described above is concluded between the creditor and the debtor, and based on an agreement that when the debtor acquires possession of movables that are its constituent parts, the creditor acquires possession thereof by the method of constructive delivery, if the debtor then acquires possession of movables that currently exist as part of that aggregate, the creditor can be said to have perfected the security transfer over the said aggregate." [cite: 1]

"The effect of this perfection by constructive delivery extends to movables that subsequently become part of that aggregate, as long as the identity of the aggregate as a whole is maintained." [cite: 1]

III. Application – Validity of X Corp.'s Security Transfer Agreement:

Applying these principles, the Court found X Corp.'s agreement with A Corp. (Debtor) to be valid:

"In the present case... the Agreement herein, although its object is an aggregate of movables with fluctuating constituent parts, clearly specifies the type and quantitative range of the objective movables as 'ordinary steel bars, deformed steel bars, etc., all inventory goods,' and also specifies its location as... 'Warehouses No. 1 to No. 4 of A Corp. (Debtor) and the premises and yards thereof.' Therefore, it should be said that it is effective as a security transfer agreement over an aggregate of movables thus specified." [cite: 1] This was a significant affirmation, as prior Supreme Court cases, while recognizing the principle, had sometimes found the specifics of designation inadequate.

IV. Application – Perfection of X Corp.'s Security Interest over the Disputed Goods:

The Court also found X Corp.'s security interest to be properly perfected and to cover the Disputed Goods:

"...based on the agreement that when A Corp. (Debtor) acquired possession of movables that are its constituent parts, X Corp. would acquire possession thereof by the method of constructive delivery, it cannot be denied that A Corp. (Debtor) did in fact acquire possession of the said movables. Therefore, it can be construed that X Corp. acquired a security transfer right over the said aggregate for which the requirements for perfection against third parties had been met... And, as there is no lack of identity between the said aggregate and the aggregate that subsequently included the Disputed Goods as a part of its constituent elements, X Corp. can be said to be able to assert its security transfer right over this aggregate against third parties." [cite: 1]

V. X Corp. as a "Third-Party Acquirer" vis-à-vis Y Corp.'s Statutory Preferential Right:

Finally, the Court addressed the conflict with Y Corp.'s claimed seller's preferential right:

"Therefore, with respect to the Disputed Goods as well, X Corp. can be said to assert a security transfer right as one who has received delivery thereof. In the present case, where there are no assertions or proof of special circumstances, X Corp. falls under the category of a third-party acquirer as stipulated in Article 333 of the Civil Code, and as such, can bring an action to seek the prohibition of the movable property auction initiated by Y Corp. based on the aforementioned preferential right." [cite: 1]

Article 333 of the Civil Code states that a preferential right (such as a seller's preferential right over goods for the unpaid price) generally cannot be exercised against movables once the debtor has delivered them to a "third-party acquirer." The Supreme Court found that X Corp., through its perfected security transfer over the entire, continuously replenished inventory, was effectively such a "third-party acquirer" with respect to all goods (including the Disputed Goods) that became part of that inventory. Thus, X Corp.'s security interest took priority over Y Corp.'s unexercised seller's preferential right.

Key Concepts: "Aggregate of Movables" and Perfection by Constructive Delivery

This judgment solidifies two crucial concepts for securing inventory in Japan:

- "Aggregate of Movables" (Shūgō Dōsan) as a Single Object of Security: Japanese law, through judicial interpretation, allows a fluctuating collection of movable goods (like inventory) to be treated as a single, identifiable object for the purpose of a security transfer. This avoids the impracticality of creating separate security interests over each individual item as it enters or leaves the inventory. The key is that the "aggregate" itself must be clearly defined.

- Perfection by Constructive Delivery (Sen'yū Kaitei) for Aggregates, Including Future Additions: The security interest in such an aggregate can be perfected against third parties by "constructive delivery." This typically involves an agreement where the debtor (who retains physical possession for operational purposes) acknowledges that they now hold the goods on behalf of the creditor. The Supreme Court confirmed that an initial act of constructive delivery covering the defined aggregate, coupled with an agreement that new items falling within the aggregate's definition will also be covered, perfects the creditor's interest over the entire aggregate as it exists and as it is replenished, without needing a new act of constructive delivery for each newly acquired item, as long as the aggregate maintains its overall identity.

The Specificity Requirements for Identifying the Aggregate

For a security transfer over an aggregate of movables to be valid and effective, the "aggregate" must be clearly identified. The Supreme Court in this case endorsed the criteria of specifying:

- Type of Goods: In this case, "ordinary steel bars, deformed steel bars, etc., all inventory goods" was deemed sufficiently specific. Legal commentary suggests that while very general categories like "all raw materials" or "all inventory" might be acceptable if combined with strict location and range specifiers, overly vague descriptions like "all household effects" have been rejected by the Court in other contexts.

- Location: The goods must be located within a clearly defined physical space. Here, "Warehouses No. 1 to No. 4 of A Corp. (Debtor) and the premises and yards thereof" met this requirement.

- Quantitative Range: The judgment found "all inventory goods" at the specified location to be a valid specification of range. This contrasts with a prior Supreme Court case where specifying a portion of a larger mass (e.g., "28 tons of X out of a larger quantity of X at a location") was found to be insufficiently specific because it didn't identify which 28 tons were secured. Designating "all" items of a certain type at a location can thus be a more effective way to define the quantitative scope.

Impact on Inventory Financing and Seller's Rights

This 1987 Supreme Court judgment was a landmark for several reasons:

- Facilitated Inventory Financing: It provided strong judicial backing for a practical and legally robust method of securing loans against fluctuating inventories, which is vital for many businesses. By recognizing the "aggregate of movables" concept and the continuing effect of an initial perfection over after-acquired items within that aggregate, it reduced the transactional costs and complexities that would arise from trying to secure inventory on an item-by-item basis.

- Clarified Priority: It clarified the priority relationship between a holder of a perfected security transfer over an aggregate inventory and a supplier of goods who relies solely on their statutory preferential right for the sale of movables. The security transfer holder, being deemed a "third-party acquirer" who has "received delivery" of items entering the secured pool, generally takes precedence over the supplier's unexercised preferential right for those specific items. This means suppliers selling goods on credit to businesses whose inventory is already comprehensively pledged via a security transfer need to be aware that their statutory preferential right might be subordinate.

Subsequent Legal Developments

The legal landscape for security over movables in Japan has continued to evolve since this 1987 judgment:

- Movable Assignment Registration System: In 2004, a special law established a public registration system for the assignment (including security transfer) of movables (and also claims). This system provides an alternative method to constructive delivery for perfecting security interests in movables against third parties. Registration requires specific details to identify the movables, and for fluctuating aggregates specified by location, it typically requires a description of the type of movables and the precise location of storage, often with more detail than the minimum judicial requirements for constructive delivery.

- Ongoing Security Law Reforms: Since 2021 (Reiwa 3), legislative bodies in Japan have been working on further reforms to the laws governing security over movables, claims, and other assets. These ongoing efforts may lead to codification or further refinement of the rules established by judicial precedents like this 1987 Supreme Court judgment.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of November 10, 1987, was a pivotal decision that validated and provided essential clarity on the creation, perfection, and priority of security transfer interests over fluctuating aggregates of movables, such as inventory. By establishing practical criteria for defining the scope of the secured assets and affirming that an initial act of perfection can extend to after-acquired goods falling within that defined aggregate, the Court endorsed a vital legal mechanism for inventory financing. Furthermore, by defining the priority of such a perfected security transfer over a seller's statutory preferential right, the judgment provided important guidance for commercial transactions and creditor rights in Japan. This ruling remains a cornerstone of Japanese law on security over movable assets.