Securing Debts Across Borders: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Pledging Bank Deposits

Date of Judgment: April 20, 1978

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

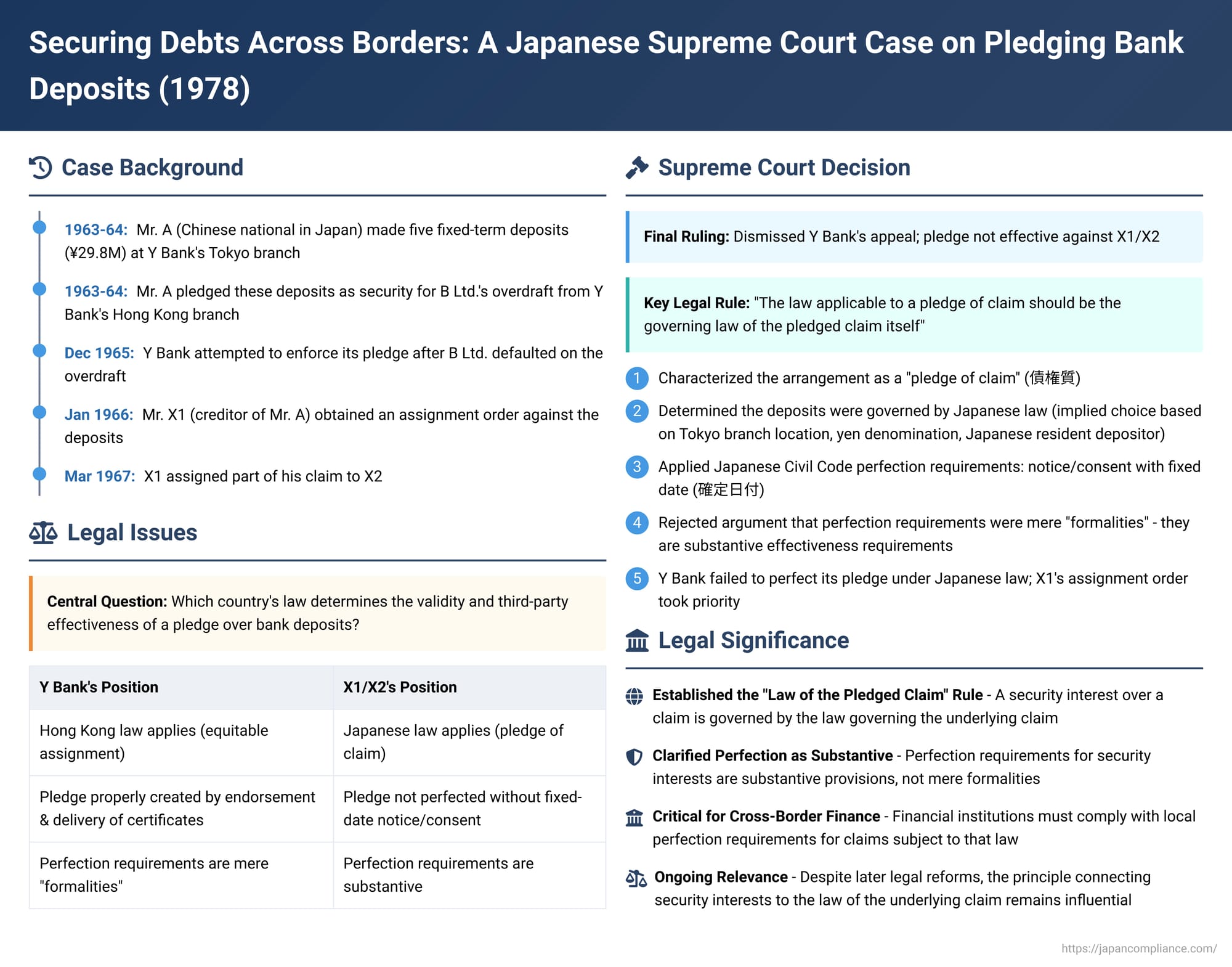

In the world of international finance, taking security over assets to guarantee loans or other obligations is a fundamental practice. When these assets are intangible, such as bank deposits or contractual rights (claims), and the parties or assets are connected to multiple countries, complex legal questions arise: Which country's law governs the creation and effectiveness of the security interest, especially against third parties? A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision from April 20, 1978, addressed these intricate issues in the context of a pledge over fixed-term bank deposits, offering crucial guidance on the applicable private international law rules.

The Factual Background: A Cross-Border Loan and a Disputed Pledge

The case involved a series of international financial dealings:

- Mr. A, a Chinese national residing in Japan, sought an overdraft facility from the Hong Kong branch of Y Bank (a foreign bank headquartered in Bangkok). Mr. A was the representative of a foreign company, B Ltd., which would use the overdraft.

- Due to Mr. A's residence in Japan making it difficult for the Hong Kong branch to assess his creditworthiness, Y Bank Hong Kong agreed to the overdraft facility on the condition that Mr. A create fixed-term deposits at Y Bank's Tokyo branch and pledge these deposits as security.

- Between 1963 and 1964, Mr. A made five fixed-term deposits totaling 29.8 million yen at Y Bank's Tokyo branch ("the Deposits").

- To effect the security arrangement, Mr. A signed the designated sections for receipt of principal and interest on the reverse side of the five deposit certificates (leaving the date fields blank) and delivered these endorsed certificates to Y Bank's Hong Kong branch. The Hong Kong branch then notified the Tokyo branch of this security setup.

- B Ltd. subsequently drew down a total of 440,000 Hong Kong dollars under the overdraft facility but failed to repay the amount by the due date.

- In December 1965, Y Bank's Hong Kong branch decided to enforce its security. It sent the deposit certificates to Y Bank's Tokyo branch, requesting the cancellation of the Deposits and the transfer of the proceeds to the Hong Kong branch.

- However, Y Bank's Tokyo branch did not cancel the Deposits at that time, citing anticipated difficulties in obtaining the necessary approval for such a remittance to Hong Kong under Japan's foreign exchange control regulations then in force.

Meanwhile, a separate creditor entered the picture:

- Mr. X1 (a plaintiff) had lent a total of 32 million yen to Mr. A in 1963.

- Following a dispute over repayment of this loan, a court-mediated settlement was reached, requiring Mr. A to pay X1 32 million yen by December 25, 1965. Mr. A failed to make this payment.

- In January 1966, Mr. X1 initiated compulsory execution proceedings against Mr. A's assets, targeting the Deposits held at Y Bank's Tokyo branch. He obtained an "assignment order" (転付命令 - tempu meirei), a court order that effectively transfers the garnished claim (the deposit claims) to the judgment creditor (X1).

- In March 1967, Mr. X1 assigned a portion of the claim he had acquired through this assignment order to Mr. X2 (also a plaintiff).

Messrs. X1 and X2 subsequently sued Y Bank for the payment of the principal and interest of the Deposits. Y Bank defended its position by arguing that the Deposits had been pledged as security for B Ltd.'s overdraft, and since B Ltd. had defaulted, Y Bank had enforced its security rights, effectively cancelling the Deposits and applying the funds to the outstanding debt. Therefore, Y Bank contended, the deposit claims no longer existed or were subordinate to its prior security interest.

The Core Conflict of Laws Question: Which Law Governs the Pledge?

This defense raised a critical conflict of laws issue: Which country's law should determine the validity of the security interest created over the Deposits and, crucially, its effectiveness (or "perfection") against third parties like X1, the attaching creditor?

- Y Bank argued that Hong Kong law (specifically, English law as it was applied in Hong Kong at the time) governed the transaction, which it characterized as an "equitable assignment" for security.

- X1 and X2 contended that Japanese law was the governing law, and under Japanese law, Y Bank's security interest (which they viewed as a pledge) had not been properly perfected to be effective against them.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed Y Bank's appeal, ruling in favor of X1 and X2. The Court's reasoning systematically addressed the choice of law issues:

1. Characterization of the Security Interest:

The Supreme Court first characterized the security arrangement – where Mr. A endorsed and delivered the deposit certificates to Y Bank's Hong Kong branch – as an agreement to create a "pledge of claim" (債権質 - saiken-shichi). (It's worth noting that academic commentary, such as that by Professor Morishita, has questioned whether using this specific Japanese legal term at the characterization stage was ideal, as it might prematurely narrow the scope and exclude functionally similar foreign security concepts like security assignments. Y Bank itself had argued for an equitable assignment under Hong Kong law, a point not extensively analyzed by the Court after this initial characterization.)

2. Governing Law of the Pledge of Claim:

The Court then laid down a crucial rule for determining the applicable law for such a pledge of claim. It referenced Article 10(1) of the old Horei (Japan's then-prevailing Act on Application of Laws), which stated that rights in rem (property rights) in movables and immovables are governed by the law of the situs of the object. The rationale is that such rights, involving exclusive control, are closely tied to the interests of the place where the object is located.

The Court reasoned that while a pledge of a right is a type of right in rem, its object is an intangible property right itself, not a physical thing, making it impossible to directly ascertain a "situs" in the physical sense. However, a pledge of a right directly controls the pledged right and affects its legal fate. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the law applicable to a pledge of claim should be the governing law of the pledged claim itself.

3. Governing Law of the Pledged Deposits:

Following this logic, the next step was to determine the governing law of the underlying pledged assets – the fixed-term deposit agreements between Mr. A and Y Bank's Tokyo branch. The Supreme Court, affirming the lower court, found that these deposit agreements were governed by Japanese law. This determination was based on an implied choice of law by the parties (under Horei Article 7(1)). Factors supporting this implied choice included: Y Bank's Tokyo branch was operating in Japan under Japanese banking regulations; Mr. A was a resident of Japan when he made the yen-denominated deposits; and the deposit contracts were standard-form adhesion contracts typically used for banking transactions in Japan. The Court viewed the fact that these deposits were intended as security for an overdraft from Y Bank's Hong Kong branch as merely the motive for entering into the deposit agreements, not as an indication of an implied choice of Hong Kong law to govern the deposit claims themselves.

4. Perfection of the Pledge under Japanese Law:

Since Japanese law was determined to govern the pledge of claim (as it governed the underlying deposit claims), the provisions of the Japanese Civil Code concerning the perfection of such pledges against third parties became applicable. Article 364(1) of the Japanese Civil Code stipulated that for a pledge over a nominated claim (like a bank deposit) to be effective against the debtor of the pledged claim (in this case, Y Bank Tokyo, regarding Mr. A's deposit) or other third parties (like Mr. X1), certain perfection requirements must be met. These requirements, mirroring those for the assignment of claims under Article 467 of the Civil Code, involved either:

* Notifying the third-party debtor (Y Bank Tokyo) of the pledge using an instrument with a "fixed date" (確定日付のある証書 - kakutei hizuke no aru shōsho), or

* Obtaining the third-party debtor's (Y Bank Tokyo's) consent to the pledge, also evidenced by an instrument with a fixed date.

A "fixed date" is a formal certification (e.g., from a notary or through content-certified mail) that proves a document existed on a particular date, preventing later fabrication or antedating.

5. Notice/Consent Not a Mere "Formality":

Y Bank argued that these notice and consent requirements were matters of "formality" of a legal act. If so, under Horei Article 8(2), the law of the place where the act was performed (lex loci actus, potentially Hong Kong, where the pledge agreement might have been centered) could validate the form even if it didn't meet Japanese formal requirements. The Supreme Court firmly rejected this argument. It held that the requirement for notice to, or consent from, the third-party debtor with a fixed-date certificate was not merely a matter of the form of the pledge agreement. Instead, it was a substantive requirement for the effectiveness (perfection) of the pledge of claim against third parties. Thus, Horei Article 8 concerning formalities was not applicable to this particular issue.

Outcome and Significance

Because Y Bank had not complied with the Japanese law requirements for perfecting its pledge over Mr. A's deposits (i.e., by providing notice to its Tokyo branch with a fixed-date certificate or obtaining its fixed-date consent regarding the pledge from its Hong Kong branch), its security interest was not effective against Mr. X1. Consequently, Mr. X1's subsequent assignment order, obtained through court execution proceedings, took priority over Y Bank's unperfected pledge. The Supreme Court, therefore, dismissed Y Bank's appeal.

Key principles and implications from this case, as highlighted by academic commentary, include:

- The "Law of the Pledged Claim" Rule: This case established a clear rule in Japanese private international law: the governing law for a pledge over a claim is the law that governs the pledged claim itself. This connects the security interest directly to the legal regime of the underlying asset.

- Perfection as a Substantive Requirement: The Court's determination that fixed-date notice or consent for perfecting a pledge of claim is a matter of substantive effectiveness, not mere formality, has significant practical implications. Parties taking security over claims subject to Japanese law must adhere to these stringent perfection rules to protect their interests against third parties.

- Characterization in PIL: The initial step of characterizing the legal issue (here, as a "pledge of claim") is crucial and can influence the subsequent choice-of-law analysis. Using terms rooted in one domestic legal system may inadvertently exclude consideration of functionally equivalent concepts from other legal systems.

- Ongoing Evolution: While this case was decided under the old Horei, the principles regarding the law governing security over claims continue to be relevant. Professor Morishita's commentary notes a modern trend towards advocating for a unified private international law approach for all types of security interests in claims (including pledges, security assignments, etc.), potentially aligning their treatment with the rules for the assignment of claims against third parties, which also often points to the law of the underlying claim.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1978 decision in the "Bangkok Bank" case remains a cornerstone for understanding the conflict of laws treatment of pledges over claims in Japan. It underscores that the effectiveness of such security interests, particularly against third parties, is determined by the law governing the pledged claim itself. For financial institutions and parties involved in international transactions where claims subject to Japanese law are pledged as security, this ruling emphasizes the critical importance of adhering to Japanese perfection requirements, such as obtaining a fixed-date certificate for notices or consents, to ensure the robustness of their security. The case serves as a vital reminder of the meticulous attention required for structuring and perfecting cross-border security arrangements.