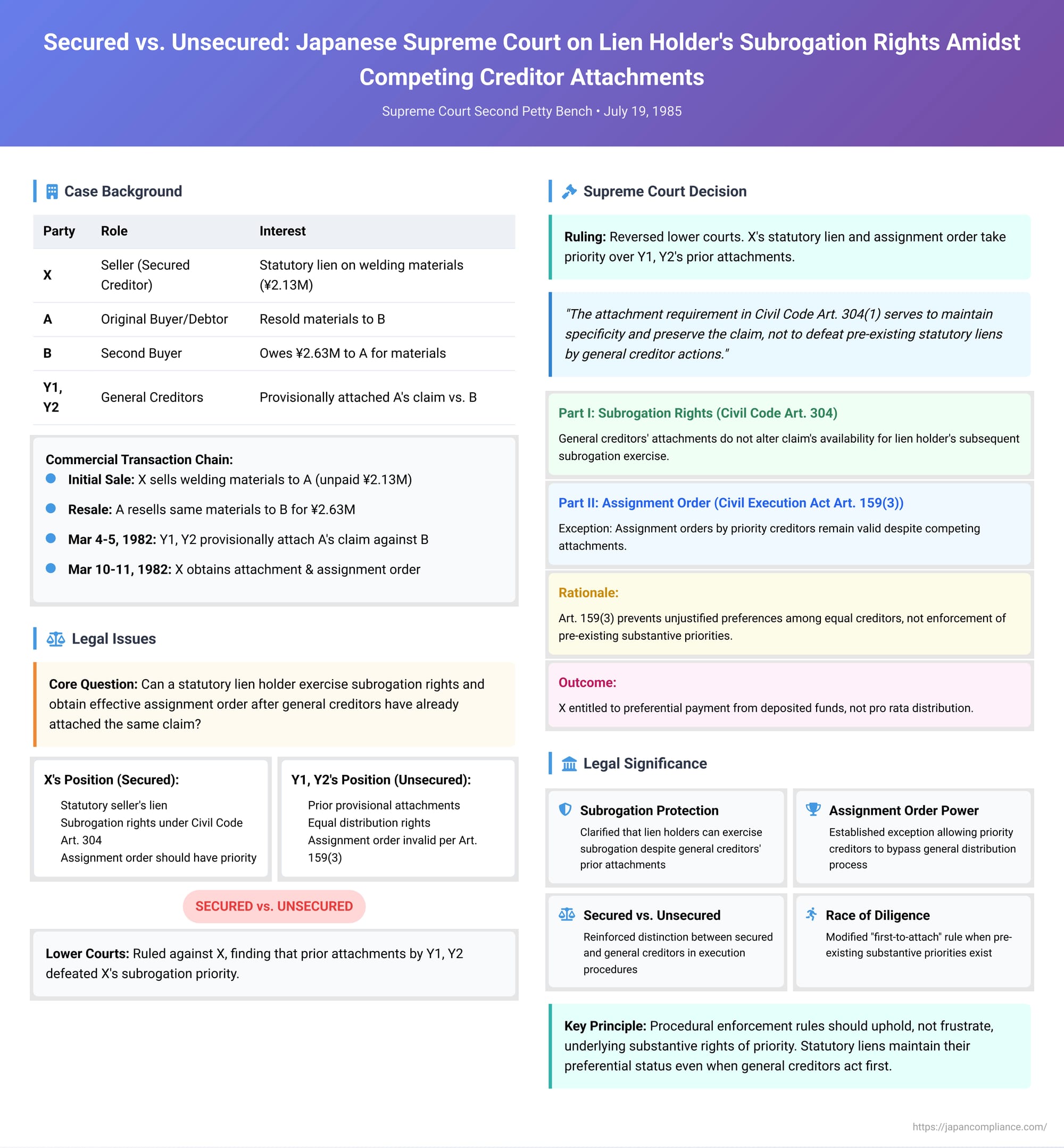

Secured vs. Unsecured: Japanese Supreme Court on Lien Holder's Subrogation Rights Amidst Competing Creditor Attachments

Date of Supreme Court Decision: July 19, 1985

The world of debt recovery often resembles a race, with creditors employing various legal tools to secure repayment from a common debtor. A critical distinction in this race lies between secured creditors, who possess specific rights over certain assets, and general unsecured creditors. A significant 1985 decision by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Showa 58 (O) No. 1548) brought clarity to a complex scenario involving a creditor with a statutory seller's lien exercising a right of subrogation, and general creditors who had already taken steps to attach the same asset—a monetary claim. This ruling addressed two pivotal questions: first, whether a statutory lien holder can still effectively exercise their right of subrogation over a claim after general creditors have provisionally attached it; and second, the validity of an "assignment order" obtained by such a lien holder in the face of these prior attachments.

The Commercial Setting: A Chain of Sales, Debts, and Legal Maneuvers

The case arose from a series of commercial transactions and subsequent debt recovery actions:

- The Initial Sale and Lien: X, a company, sold welding materials to A. For the unpaid sales price (over ¥2.13 million), X held a statutory lien over those specific goods (動産売買の先取特権 - dousan baibai no sakidori tokken), a non-possessory security interest provided by the Japanese Civil Code to sellers of movable goods.

- Resale and the Right of Subrogation: A subsequently resold these same welding materials to B for a sum exceeding ¥2.63 million. Under Japanese law (Civil Code Art. 304), when the subject matter of a statutory lien (the goods) is sold, the lien holder (X) can exercise a right of subrogation (物上代位 - butsujō daii) against the monetary claim that the original debtor (A) acquires from the resale buyer (B) – in this case, the proceeds of the resale.

- General Creditors' Actions: Before X took formal steps to exercise this subrogation right, two general creditors of A, namely Y1 and Y2, acted. On March 4 and 5, 1982, respectively, Y1 and Y2 obtained provisional attachment orders (仮差押命令 - kari sashiosae meirei) against A’s claim for the resale price from B. These orders were duly served on B, the third-party debtor, effectively freezing that portion of the debt owed to A.

- Lien Holder's Enforcement: Shortly thereafter, on March 10, 1982, X moved to enforce its statutory lien via subrogation. X obtained from the Osaka District Court both an attachment order (差押命令 - sashiosae meirei) and, crucially, an assignment order (転付命令 - tempu meirei) concerning A’s claim against B, up to the amount of X's outstanding sales credit (over ¥2.13 million). These orders were served on B on March 11, 1982. An assignment order, if effective, transfers the attached claim directly from the debtor (A) to the enforcing creditor (X), making X the new creditor of the third-party debtor (B).

- Deposit and Distribution Dispute: Faced with these competing claims and court orders, B deposited the full amount of the resale price owed to A with the court (a procedure known as 供託 - kyōtaku). The execution court then prepared a distribution statement (配当表 - haitōhyō) proposing to distribute the deposited funds among X, Y1, and Y2 on a pro rata basis, according to their respective claim amounts, essentially treating them as creditors of equal standing.

X objected, asserting that its statutory lien, exercised through subrogation and perfected by the assignment order, granted it priority over the general creditors Y1 and Y2. X argued it was entitled to preferential payment from the deposited funds, not just an equal share. When this objection was not sustained at the execution court level, X filed a formal lawsuit to challenge the distribution plan.

The Lower Courts: A Setback for the Lien Holder

Both the court of first instance (Osaka District Court) and the appellate court (Osaka High Court) ruled against X. Their reasoning was primarily based on their interpretation of the proviso to Article 304, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. This proviso states that to exercise the right of subrogation, the lien holder must attach the monetary claim (the proceeds) before its payment or delivery to the debtor. The lower courts interpreted this "attachment" requirement not merely as a step to identify and freeze the targeted claim, but as a crucial act for preserving the lien holder's priority against other third-party claimants. Since Y1 and Y2’s provisional attachments on A's claim against B had occurred before X executed its own attachment as part of its subrogation, the lower courts concluded that X could no longer assert its priority against Y1 and Y2.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Upholding the Lien Holder's Priority

The Supreme Court, in its decision of July 19, 1985, decisively overturned the lower courts' rulings and found in favor of X. The judgment meticulously addressed the two critical legal issues:

Part I: The Timeliness and Effect of Exercising Subrogation (Interpreting Civil Code Art. 304(1) Proviso)

The Supreme Court began by elaborating on the purpose behind requiring a lien holder to "attach" the claim representing the proceeds of the liened property when exercising the right of subrogation:

- Maintaining Specificity: The attachment serves to clearly identify and segregate the specific monetary claim that is the object of subrogation. This prevents it from being commingled with the debtor's other assets and losing its traceable character as proceeds of the original collateral.

- Preserving the Claim: It prohibits the third-party debtor (B) from paying the original debtor (A), and it bars the original debtor (A) from collecting the claim or assigning it to someone else.

- Protecting Third Parties: This mechanism also aims to prevent unexpected losses to the third-party debtor who pays out the claim, or to other third parties who might legitimately acquire rights to the claim (e.g., through a subsequent assignment from A or an assignment order).

Based on this understanding, the Supreme Court reasoned that if general creditors (like Y1 and Y2) have merely executed an attachment or provisional attachment on the targeted claim, this action alone does not fundamentally alter the claim's status in a way that would preclude a statutory lien holder from subsequently exercising their right of subrogation. The prior attachments by general creditors do not remove the claim from A's estate for the benefit of Y1 and Y2 in a definitive sense that would defeat X's pre-existing, albeit unexercised, proprietary interest via the lien. The claim's "specificity" and availability for X's subrogation right are not destroyed by such general creditor actions. The Court referenced its earlier decision of February 2, 1984 (Showa 56 (O) No. 927) which supported this line of reasoning.

Therefore, X was not too late to exercise its subrogation rights merely because Y1 and Y2 had already provisionally attached A's claim against B.

Part II: The Efficacy of an Assignment Order Amidst Competing Attachments (Interpreting Civil Execution Act Art. 159(3))

The second crucial issue was the validity of the assignment order obtained by X, given that Y1 and Y2’s provisional attachments were already in place when X’s order was served on B. Article 159, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act generally provides that an assignment order does not take effect if, by the time it is served on the third-party debtor, other creditors have already attached, provisionally attached, or formally demanded a share in the distribution of, the same monetary claim (a situation often referred to as "competing attachments" or 差押えの競合 - sashiosae no kyōgō). The rationale for this general rule is to ensure equitable treatment among general creditors by preventing one from gaining an eleventh-hour preference through an assignment order if others have already staked a claim.

However, the Supreme Court carved out a vital exception: This general rule of invalidity under Article 159(3) does not apply if the creditor who obtained the assignment order is a creditor with a pre-existing priority right over the claim.

Since X was a statutory lien holder exercising a right of subrogation—a recognized priority right—its assignment order did take effect, notwithstanding the prior provisional attachments by the general creditors Y1 and Y2. The Court reasoned that the purpose of Article 159(3) is to prevent an unjustified preference among creditors of equal standing. It is not intended to nullify an assignment order that merely effectuates a legally recognized, pre-existing substantive priority. If the creditor obtaining the assignment order already possesses a right to be paid ahead of others from that specific asset, allowing the assignment order to take effect simply gives procedural form to that substantive priority.

Thus, X's assignment order was deemed valid and effective. This meant that A's claim against B (up to the amount secured by X's lien) was legally transferred to X as of the moment the assignment order was served on B. Consequently, X was entitled to claim those funds preferentially in the distribution of the amount B had deposited.

The Supreme Court then proceeded to set aside the original pro rata distribution plan and ordered that a new distribution table be prepared reflecting X’s priority.

Broader Implications of the Supreme Court's Decision

This 1985 ruling has had significant implications for the understanding and enforcement of security interests in Japan:

- Clarification on Exercising Subrogation (Civil Code Art. 304(1)): The decision, building on previous jurisprudence, signaled a leaning towards interpreting the "attachment" requirement for subrogation more from a "specificity maintenance" perspective (ensuring the identifiable nature of the proceeds) rather than a strict "priority perfection against all subsequent third-party actions" perspective. This allows lien holders a more robust window to exercise subrogation, as long as the proceeds have not been paid out, irretrievably commingled, or indefeasibly acquired by a third party with a clearly superior, perfected right to the claim itself.

- Status of General Creditors' Prior Attachments: The ruling underscores that a provisional attachment by a general creditor, while an important step in securing a potential recovery, is primarily a freezing measure. It does not, by itself, grant the attaching general creditor an ownership right in the attached claim or an automatic priority that would defeat a pre-existing (even if subsequently exercised) statutory lien and its associated subrogation rights.

- Potency of Assignment Orders for Priority Creditors: The judgment solidified the assignment order as a powerful tool for creditors holding priority rights. It allows them to effectively bypass a general distribution process (where they might otherwise be grouped with unsecured creditors if the priority is not recognized at that stage) and achieve direct recovery from the third-party debtor, up to the value of their secured claim.

- Protection for the Third-Party Debtor: The Court also implicitly recognized the difficult position of a third-party debtor (like B) caught between competing claims and court orders. By finding B's deposit of the funds with the court to be valid (by analogy to provisions allowing deposit in cases of uncertainty, e.g., Civil Execution Act Art. 156(2)), the decision acknowledges that such debtors cannot be expected to make definitive legal judgments about the validity and priority of competing claims, especially in complex situations involving assignment orders. Depositing the funds allows the third-party debtor to discharge their obligation and leaves the competing creditors to resolve their priorities within the court-supervised distribution process.

- The "Race of Diligence" Qualified: While creditor actions often involve a "race of diligence" to attach assets, this ruling demonstrates that a pre-existing substantive priority (like a statutory lien) can effectively alter the outcome of that race, particularly when it comes to the efficacy of powerful enforcement tools like assignment orders. An earlier attachment by a general creditor does not automatically win the day against a later-enforcing but substantively prioritised secured creditor.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 19, 1985, decision in this distribution dispute case struck a careful balance. It robustly protected the subrogation rights of statutory lien holders, ensuring that these important non-possessory security interests are not easily undermined by the prior, more general, debt recovery actions of unsecured creditors. By clarifying the purpose of the attachment requirement in Civil Code Article 304(1) and carving out a crucial exception to the general rule governing the validity of assignment orders in Civil Execution Act Article 159(3), the Court provided significant legal certainty. This ruling ensures that creditors with recognized substantive priorities can effectively realize their security, reinforcing the value and efficacy of statutory liens within the Japanese commercial and legal framework. It highlights the principle that procedural enforcement rules should, where appropriate, operate to uphold, rather than inadvertently frustrate, underlying substantive rights of priority.