Secrets of the State: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Cabinet Discretionary Fund Records

Judgment Date: January 19, 2018

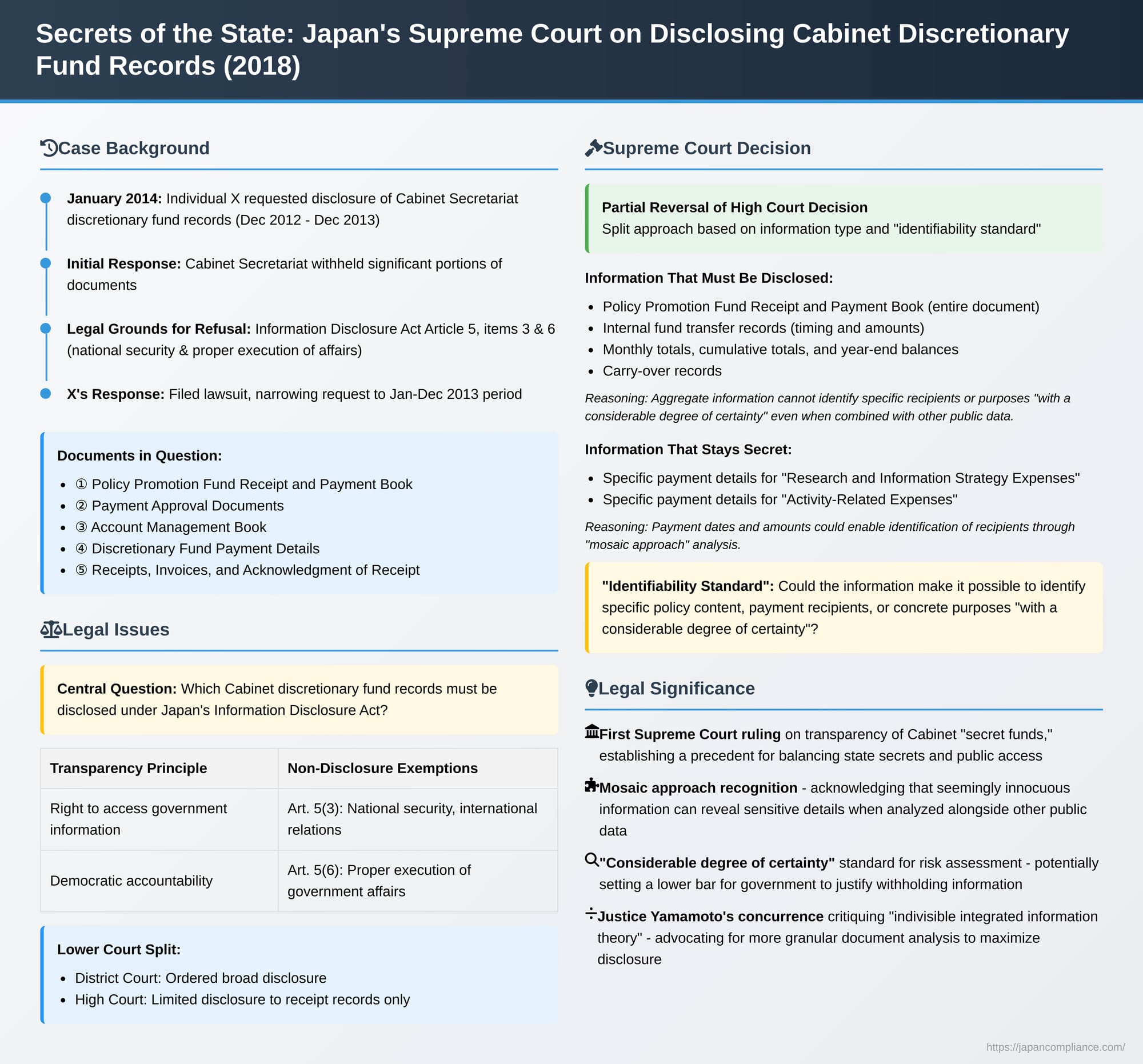

The principle of governmental transparency is a cornerstone of modern democracies, often enshrined in information disclosure laws that grant citizens the right to access information held by public institutions. However, this right is not absolute and frequently comes into tension with the government's need to protect sensitive information, particularly concerning national security, diplomatic relations, and the effective execution of policy. A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision on January 19, 2018 (Heisei 29 (Gyo-Hi) No. 46), delved into this complex balance, addressing a request for the disclosure of documents related to the Cabinet Secretariat's discretionary funds, often referred to colloquially as "secret funds" (kimitsuhi - 機密費). This case marked the first time Japan's highest court ruled on the transparency of these notoriously opaque expenditures.

The Request and The Refusal: A Bid for Transparency

In January 2014, an individual, X (the plaintiff), filed a request under Japan's Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs (hereinafter, the Information Disclosure Act). The request was made to the Cabinet Secretariat Chief Cabinet Secretary for the disclosure of administrative documents pertaining to the expenditure of the Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds (naikaku kanbō hōshōhi - 内閣官房報償費) for the period covering December 2012 to December 31, 2013.

The Cabinet Secretariat identified several categories of documents relevant to the request:

- ① Policy Promotion Fund Receipt and Payment Book (Seisaku Suishinhi Ukebaraibo)

- ② Payment Approval Documents (Shiharai Ketteisho)

- ③ Account Management Book (Suitō Kanribo)

- ④ Discretionary Fund Payment Details (Hōshōhi Shiharai Meisaisho)

- ⑤ Receipts, Invoices, and Acknowledgment of Receipt (Ryōshūsho, Seikyūsho oyobi Juryōsho)

Collectively, these were termed "the documents in question". The Cabinet Secretariat Chief Cabinet Secretary decided to withhold parts of these documents. The justification provided was that the information recorded in these documents fell under the non-disclosure provisions stipulated in Article 5, item 3 and Article 5, item 6 of the Information Disclosure Act.

Article 5, item 3 of the Act exempts information from disclosure if its release could harm national security, undermine trust with other countries or international organizations, or be detrimental to negotiations with other countries or international organizations. Article 5, item 6 exempts information concerning the affairs or business conducted by the state if its disclosure is likely to obstruct the proper execution of those affairs or business due to its nature.

Dissatisfied, X initiated a lawsuit, narrowing the request period to January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2013. X sought the cancellation of the non-disclosure decision and a court order compelling the disclosure of the withheld portions.

Navigating the Courts: The Legal Battle for Disclosure

The case progressed through the lower courts with differing results. The Osaka District Court, as the court of first instance, ordered the cancellation of the non-disclosure decision for the Policy Promotion Fund Receipt and Payment Book (①), the Discretionary Fund Payment Details (④), and parts of the Payment Approval Documents (②), Account Management Book (③), and Receipts/Invoices (⑤), mandating their disclosure.

The Osaka High Court, in the second instance, took a more restrictive view. It ordered the disclosure only of parts of the Account Management Book (③) that related to the receipt of discretionary funds from the national treasury. For all other contested parts, it upheld the non-disclosure decision, effectively maintaining most of the government's original stance. Both X and the State appealed to the Supreme Court, with X's petition for acceptance of the final appeal being granted.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 19, 2018): Drawing a Line

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision, ultimately ordering a more extensive disclosure than the High Court had allowed, but still upholding non-disclosure for certain sensitive details. The Court's judgment carefully delineated its reasoning based on the nature of the funds and the specific types of information.

Part I: Understanding the "Secret Funds"

The Supreme Court began by characterizing the role of the Cabinet Secretariat and its discretionary funds:

- The Cabinet Secretariat is a pivotal institution responsible for planning, drafting, and coordinating vital national matters and key Cabinet policies, as well as intelligence gathering, analysis, and crisis management.

- To effectively carry out these duties, the Cabinet Secretariat, based on the policy judgments of the Chief Cabinet Secretary at any given time, may engage in various activities. These can include informal negotiations or requests for cooperation with individuals or entities related to important domestic and foreign policies, or gathering information from external sources on significant matters.

- The Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds are expended to cover necessary costs for the smooth and effective execution of such sensitive activities.

- The Court acknowledged that Cabinet policies, particularly those concerning fundamental aspects of domestic and foreign affairs, consistently attract public attention. Especially for important policies that become the subject of discretionary fund expenditures, a high degree of interest exists, and it is probable that various means will be employed to actively collect and analyze related information.

- Crucially, parties who receive informal requests for cooperation from the Cabinet Secretariat regarding important policies typically agree to cooperate on the premise that their involvement will not be made public. If information about their involvement, or information from which their involvement could be inferred, were disclosed, it could lead to a loss of trust from these parties. This, in turn, would likely hinder the execution of tasks related to important policies. Moreover, it could lead to a reluctance to cooperate with or provide information to the Cabinet Secretariat in the future, thereby potentially obstructing the overall activities of the Cabinet Secretariat.

- The Court also noted that if the names or titles of such cooperating parties were revealed, it could open them up to improper pressure or interference, threaten their safety, or lead to information leaks, thereby hindering the smooth and effective execution of the Cabinet Secretariat's activities.

Part II: What Stays Secret? (Non-Disclosure Upheld)

Based on this understanding of the funds' nature, the Supreme Court upheld the non-disclosure of certain specific payment details. This pertained to records within the "Discretionary Fund Payment Details" (Hōshōhi Shiharai Meisaisho) that related to expenditures categorized as "Research and Information Strategy Expenses" (Chōsa Jōhō Taisakuhi) and "Activity-Related Expenses" (Katsudō Kankehi).

The Court reasoned that even if disclosing these records did not immediately reveal the recipients or the exact purposes of the payments, it would make public the payment decision dates and specific payment amounts. Taking into account the sensitive nature of the Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds, and depending on factors such as the prevailing domestic and international political situation, ongoing policy challenges, significant events the Cabinet Secretariat might be addressing, or the actions of the Chief Cabinet Secretary, it could become possible for an analyst to identify the recipients or specific purposes with "a considerable degree of certainty" (sōtō teido no kakujitsusa) by cross-referencing this disclosed data with other available information. This method of piecing together information is often referred to as the "mosaic approach".

Therefore, the Supreme Court found that disclosing such specific payment details was reasonably likely to obstruct the proper execution of affairs concerning Japan's important national policies, falling under the exemption in Article 5, item 6 of the Information Disclosure Act.

Furthermore, for any such information that pertained to Japan's diplomatic relations or the interests of other countries or similar entities, the Court found that the Chief Cabinet Secretary's judgment—that disclosure could harm national security, undermine trust with other nations, or place Japan at a disadvantage in negotiations (Article 5, item 3)—had reasonable grounds. Consequently, this category of information was deemed to fall under the non-disclosure provisions of the Act.

Part III: What Must Be Revealed? (Disclosure Ordered)

In contrast, the Supreme Court ordered the disclosure of other categories of information, finding that they did not pose the same risk:

- The entirety of the "Policy Promotion Fund Receipt and Payment Book" (Seisaku Suishinhi Ukebaraibo).

- Records within the "Account Management Book" (Suitō Kanribo) and the "Discretionary Fund Payment Details" (Hōshōhi Shiharai Meisaisho) that specifically pertained to the transfer of funds into the Policy Promotion Fund (this fund is a subset of the overall discretionary budget, managed directly by the Chief Cabinet Secretary for highly sensitive policy promotion activities). The Court found that disclosing the timing and amounts of these internal transfers, or the total amount paid out from the Policy Promotion Fund between such transfers, would reveal only that limited information.

- Records from the "Account Management Book" detailing monthly totals, cumulative totals, and year-end balances (referred to as getsubunkei tō kiroku bubun), as well as carry-over records (kurikoshi kiroku bubun) from the "Discretionary Fund Payment Details". Disclosure here would only reveal the total payments from the Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds each month, cumulative payments up to a specific month in the fiscal year, and any remaining balance at the end of the fiscal year.

The Court reasoned that a transfer of funds into the Policy Promotion Fund is merely an internal administrative act of allocating a portion of the broader Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds for use under that specific category. Revealing the timing or amount of such an internal transfer does not, in itself, directly disclose the dates or amounts of individual payments subsequently made to external recipients from that fund. Similarly, revealing the total amount paid out from the Policy Promotion Fund or the overall discretionary funds over a certain period does not indicate whether these payments were made in a single installment or multiple installments, or whether they went to a single recipient or multiple recipients.

Therefore, even considering the sensitive nature of the discretionary funds, the Court concluded that it would be difficult to identify the specific content of policies the Cabinet was trying to promote, the payment recipients, or the concrete purposes of these expenditures with "a considerable degree of certainty" solely from this type of aggregate or transfer information. This conclusion held even in light of evidence that, during the period in question, transfers into the Policy Promotion Fund were sometimes made frequently (e.g., two or three times a month) and the fund was nearly depleted before the next transfer occurred.

Consequently, the Supreme Court ruled that this latter category of information did not fall under the non-disclosure exemptions of Article 5, item 3 or item 6 of the Information Disclosure Act.

Key Legal Principles and Interpretations

The Supreme Court's decision, and the commentary surrounding it, highlighted several important legal interpretations:

- The "Identifiability Standard" (tokutei kanōsei kijun): The core test applied by the Court for both the national security exemption (Art. 5, item 3) and the administrative affairs exemption (Art. 5, item 6) was whether the disclosure would make it possible to identify specific policy content, payment recipients, or concrete purposes with "a considerable degree of certainty". The lower courts had also used this standard, with the divergence in their conclusions stemming from differing assessments of the likelihood of such identification.

- Adoption of the "Mosaic Approach": The Court's reasoning, particularly concerning the non-disclosure of specific payment dates and amounts, implicitly adopted a "mosaic approach". This means that in assessing the risk of harm from disclosure, consideration is given to whether the information, when combined with other publicly available data or knowledge, could lead to the revelation of sensitive details. The commentary further suggests the Court envisaged the analyst performing this mosaic analysis not merely as an ordinary member of the public, but potentially as someone possessing special information or advanced analytical capabilities.

- Interpretation of "Likely to Obstruct" (osore): The term "osore" (おそれ), meaning "likely to" or "risk of," is central to many exemptions in the Information Disclosure Act. The first instance court had interpreted this under item 6 as requiring "a legally protectable degree of probability, not mere statistical possibility". The High Court modified this to "possessing the probability to cause the hindrance specified in the item". The Supreme Court, while not offering a general definition of "osore," employed the "identifiability standard" and used phrasing like "it is conceivable that it may become possible... to identify... with a considerable degree of certainty". This, according to legal commentary, might suggest a certain relaxation of the burden of proof for the government when claiming non-disclosure, implying a more cautious approach by being sensitive to the possibility of identification even if not a certainty. The Supreme Court's avoidance of the term "probability" (gaizensei - 蓋然性), a word typically used to express the standard degree of proof in legal contexts, also fueled interpretations that it might be applying a somewhat lower standard for establishing the "likelihood" of harm.

- Nuanced Approach to Discretionary Review: While the lower courts explicitly stated they would conduct a review for abuse of discretion by the administrative agency head, particularly regarding the national security exemption (Art. 5, item 3), respecting the agency's primary judgment if it fell within a reasonable scope, the Supreme Court's judgment did not make an explicit statement about conducting such a discretionary review. However, legal commentary suggests that the absence of such a statement, or the application of the same "identifiability standard" to both item 3 (where administrative discretion is often recognized) and item 6, does not necessarily mean the Supreme Court denied the existence of discretion for item 3. Instead, when the Court determines that information is "identifiable," it likely implicitly means that "there are reasonable grounds for the administrative agency head to deem it identifiable," thus incorporating a degree of deference.

A Justice's Call for Granular Analysis: The "Information Unit Theory" Debate

A noteworthy aspect of the Supreme Court's judgment was a concurring opinion by Justice Tsuneyuki Yamamoto. While agreeing with the majority's overall conclusion on what should be disclosed, Justice Yamamoto voiced significant concerns about a legal concept known as the "indivisible integrated information theory" (dokuritsu ittaiteki jōhō ron - 独立一体的情報論). This theory, which had been referenced in a 2001 Supreme Court decision and discussed by the lower courts in the present case, suggests that if a piece of information is deemed an "indivisible integrated whole," and part of it is non-disclosable, then the entire unit might be withheld, potentially broadening the scope of non-disclosure.

Justice Yamamoto criticized this theory on several grounds:

- The definition and scope of what constitutes "indivisible integrated information" can vary significantly depending on the person or perspective applying the theory.

- It presents technical difficulties in adequately considering the interconnectedness of individual pieces of information from the specific viewpoint of promoting information disclosure.

- Most fundamentally, it carries an inherent risk of unduly expanding the range of non-disclosed information, which runs contrary to the basic purpose of the Information Disclosure Act.

Instead of engaging in abstract discussions about the boundaries of an "indivisible unit," Justice Yamamoto advocated for a more direct and granular approach. He argued that the proper method is to examine individual components of information within a document (such as sentences, paragraphs, or specific fields in a table), consider their interrelationships, and then determine whether each component, in light of these relationships, falls under the non-disclosure provisions of Article 5. This, he suggested, is both necessary and sufficient, and avoids the pitfalls of the "indivisible integrated information theory". The commentary notes that many scholars also argue for a change in the precedent regarding this theory.

Implications for Transparency and Government Accountability

This Supreme Court ruling was a landmark, being the first to directly address the disclosure of records related to the Cabinet Secretariat's sensitive discretionary funds. It attempts to strike a delicate balance: on one hand, acknowledging the legitimate need for the government to conduct certain sensitive operations discreetly, and on the other, upholding the public's right to know, which is essential for ensuring government accountability.

The decision to differentiate between specific payment details (which could, through mosaic analysis, reveal sensitive operations) and more aggregate or internal transfer data (which are less likely to do so) provides a framework for future disclosure requests concerning similar sensitive expenditures. The "identifiability standard," requiring a "considerable degree of certainty," serves as the key benchmark. The ongoing debate, highlighted by Justice Yamamoto's opinion, over how information should be segmented or aggregated for disclosure purposes, indicates that the quest for the right balance in transparency law is a continuing process.

Conclusion

The January 19, 2018, Supreme Court judgment offers a nuanced approach to a contentious area of information disclosure. By mandating the release of certain types of records related to the Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds while protecting others, the Court affirmed that even highly sensitive government expenditures are not entirely beyond the reach of public scrutiny. The "identifiability standard" provides a critical, if challenging, tool for line-drawing. The case also brought to the forefront important methodological questions about how courts and administrative agencies should analyze and potentially sever information within documents, ensuring that the exemptions to disclosure are not applied more broadly than necessary to protect legitimate state interests.