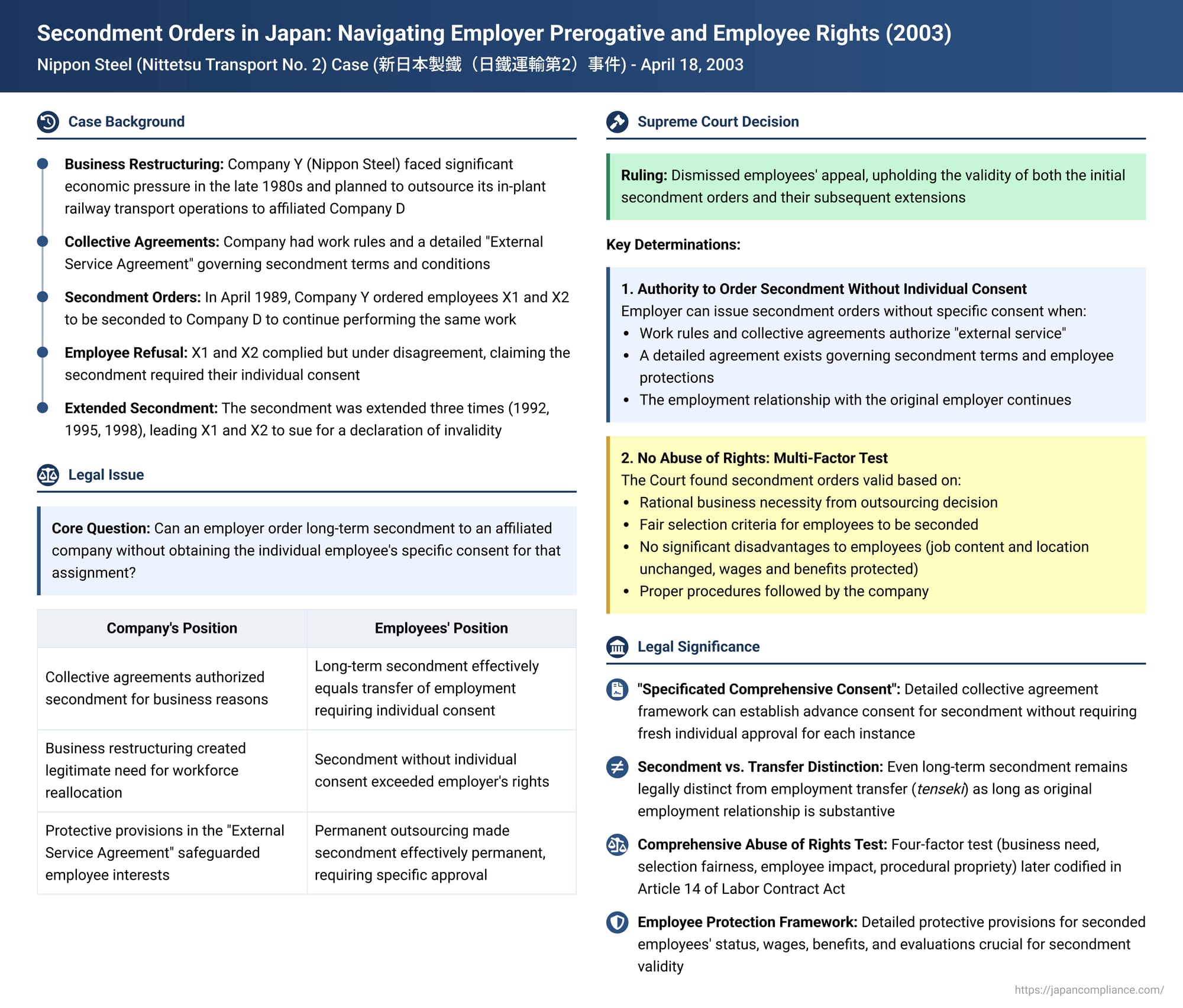

Secondment Orders in Japan: Navigating Employer Prerogative and Employee Rights (April 18, 2003)

On April 18, 2003, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case known to commentators as the "Nippon Steel (Nittetsu Transport No. 2) Case" (新日本製鐵(日鐵運輸第2)事件). This ruling addressed the validity of an employer's orders for employees to undertake long-term secondment (出向 - shukkō) to an affiliated company, particularly when these secondments stemmed from business restructuring and the employees had not given their individual consent to the specific assignments. The case is a leading authority on the legal basis for an employer's power to order secondments and the judicial standards for reviewing whether such orders constitute an abuse of rights.

Restructuring and the Secondment Mandate

The defendant, Company Y, was a major steel manufacturing and sales corporation, formed through the merger of Company A and Company B in 1970. The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, had been employed since 1961, originally by Company A, and were engaged in in-plant transportation services within Company Y. They were members of the C Labor Union.

The context for the dispute was a period of significant economic pressure on Company Y and the broader Japanese steel industry in the late 1980s, marked by a rapid appreciation of the yen and substantial financial losses for the company. In response, Company Y embarked on a business rationalization plan. A key component of this plan, decided in 1988 after consultations with the C Labor Union, was to outsource its in-plant railway transportation department to an affiliated company, Company D.

This outsourcing decision led to Company Y's plan to second employees from its railway department, including Plaintiffs X1 and X2, to Company D to continue performing essentially the same work. The selection of employees for secondment was based on criteria designed to ensure the necessary skills for the outsourced operations, generally excluding younger and older employees. While the majority of the 141 employees targeted for secondment agreed to the arrangement, X1 and X2, despite numerous discussions and persuasion attempts by Company Y, did not consent.

Nevertheless, in April 1989, Company Y formally issued orders for X1 and X2 to be seconded to Company D. They complied with these orders but did so under disagreement. Their secondment periods were subsequently extended by Company Y on three occasions: in 1992, 1995, and 1998.

The Contractual Framework for Secondment

Company Y's ability to order such external assignments was rooted in its existing employment framework:

- Work Rules and General Collective Agreement Clause: Both Company Y's work rules and the general collective agreement applicable to members of the C Labor Union contained provisions stating that the company could assign employees to "external service" (社外勤務 - shagai kinmu) for business reasons.

- Specific "External Service Agreement": More importantly, a detailed "External Service Agreement" (社外勤務協定 - shagai kinmu kyōtei), which itself was a collective agreement, governed the terms and conditions of such secondments. This agreement included specific clauses concerning:

- The definition of external service and the duration of secondment (principally up to 3 years, but extendable if business needs required).

- The seconded employee's status, stipulating that working hours, holidays, and leave during secondment would follow the regulations of the host company (Company D).

- Protections for the seconded employees' financial interests, such as a provision that if the salary at the host company was lower than their Company Y salary, Company Y would make up the difference.

- Other detailed provisions addressing retirement benefits, various secondment allowances, and procedures for performance evaluations related to promotions and salary increases, all designed to safeguard the interests of seconded employees.

Dissatisfied with the involuntary secondment and its repeated extensions, X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that Company Y's initial secondment orders were invalid. Both the Fukuoka District Court (Kokura Branch) and the Fukuoka High Court dismissed their claims, upholding the validity of both the initial secondment orders and the subsequent extensions. X1 and X2 then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Secondment Upheld

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, thereby affirming the legality of Company Y's secondment orders and their extensions.

I. Employer's Authority to Order Secondment Without Individual Consent

The Court first addressed whether Company Y had the authority to order the secondments without obtaining the specific, individual consent of X1 and X2 for these particular assignments. It concluded that such authority existed:

- The Court highlighted the presence of clauses in Company Y's work rules and the general collective agreement permitting external service for business needs.

- Crucially, it emphasized the existence of the detailed "External Service Agreement" (a collective agreement) which provided comprehensive regulations for secondments, including definitions, duration, status of employees, wage protection, retirement benefits, allowances, and evaluation processes, all demonstrating consideration for the seconded employees' interests.

Based on these established frameworks, the Supreme Court held: "Under such circumstances, Company Y can issue the secondment orders in question, ordering X1 and X2 to provide labor under the direction and supervision of the host company, Company D, while maintaining their employee status with Company Y, without their individual consent".

II. Long-Term Secondment Distinguished from Outright Transfer of Employment (Tenseki)

The plaintiffs argued that because the secondments were expected to be long-term due to the permanent nature of the outsourcing, they were tantamount to a transfer of employment (tenseki - 転籍), which would legally require their individual consent. The Supreme Court rejected this argument:

- It acknowledged that the secondments were indeed linked to outsourcing and that a long duration was anticipated from the start.

- However, it noted that the "External Service Agreement itself was concluded on the premise that there could be long-term secondments associated with outsourcing".

- The Court then clarified the key legal distinction: "The essential difference between an on-the-books secondment (在籍出向 - zaiseki shukkō, where the employee retains their employment relationship with the original employer) and a so-called transfer of employment (tenseki) lies in whether the employment contract relationship with the seconding employer (出向元 - shukkō moto) continues to exist".

- In this case, since X1 and X2 maintained their employment status with Company Y, and this relationship had not become a mere formality, "the long duration of the secondment cannot immediately be equated to a transfer of employment. The appellants' argument, which presumes this and asserts the necessity of individual consent, cannot be adopted".

III. No Abuse of Rights in the Initial Secondment Orders

The Court then examined whether the issuance of the initial secondment orders constituted an abuse of Company Y's managerial rights. It concluded that it did not, based on a comprehensive assessment:

- Business Necessity: Company Y's management decision to outsource its in-plant railway transport operations to the affiliated Company D was deemed "not lacking in rationality". Consequently, there was a legitimate "necessity to take secondment measures" for the Company Y employees who had been engaged in the work being outsourced.

- Fairness of Personnel Selection: The criteria used by Company Y to select employees for secondment were found to be "rational," and there were "no circumstances suggesting unfairness in the specific selection" of X1 and X2.

- Impact on Employees: Although X1 and X2's direct supervising entity changed to Company D, their "job content and work location remained unchanged". Furthermore, considering the protective provisions within the "External Service Agreement" regarding their status, wages, retirement benefits, various allowances, and evaluations for promotions and raises, it "cannot be said that X1 and X2 suffered significant disadvantages in their personal lives or working conditions".

- Procedural Propriety: The procedures followed by Company Y leading up to the issuance of the secondment orders were found to be "not improper".

Based on these factors, the Court held that "the secondment orders in question cannot be said to constitute an abuse of rights".

IV. No Abuse of Rights in the Secondment Extensions

The Supreme Court applied a similar analysis to the subsequent extensions of X1 and X2's secondment periods and also found them to be valid:

- Company Y's continued management decision to outsource the railway transport operations was still considered "not lacking in rationality" at the time the extensions were made.

- There was "rationality in taking measures to extend the secondment" for X1 and X2, as they were already performing the outsourced work at Company D.

- The Court concluded that it "cannot be said that X1 and X2 suffered significant disadvantages" as a result of these extensions.

Therefore, "the extensions of the secondment also do not constitute an abuse of rights".

Key Legal Principles and Their Significance

This Supreme Court judgment is a leading case on the law of secondment in Japan, particularly for "employment adjustment" type secondments arising from restructuring.

- The "Specificated Comprehensive Consent" for Secondment: The decision lends strong support to the legal theory that an employer's power to order secondment without obtaining fresh, individual consent for each instance can be established if there is a clear basis in the work rules and/or a collective agreement, provided that these instruments are not merely general clauses but are accompanied by detailed provisions (like the "External Service Agreement" in this case) that specifically address and protect the terms and conditions of employment for seconded employees. The commentary suggests this is akin to a "Concrete Agreement Theory" or "Work Rule-Collective Agreement Specific Clause Theory," where the detailed framework itself embodies a form of advance consent to the possibility of secondment under defined, protective conditions. If such provisions are too vague or abstract, the employer's power to order secondment without individual consent might not be recognized.

- Distinguishing Secondment (Shukkō) from Permanent Transfer (Tenseki): The Court clearly reiterated that the core difference lies in the continuation of the employment relationship with the original (seconding) employer. As long as this original employment link is substantive and not merely a shell, even a very long-term secondment does not automatically transform into a tenseki requiring the employee's explicit consent for transfer of the employment contract itself.

- The Multi-Factor Abuse of Rights Test for Secondment: The judgment applies a comprehensive test to determine if a secondment order is an abuse of rights, considering:

- The rationality of the underlying management decision and the necessity of the secondment measure itself.

- The rationality of the criteria used for selecting employees for secondment and the fairness of their application to the specific individuals.

- The extent of any disadvantages imposed on the seconded employees concerning their personal lives and working conditions.

- The appropriateness of the procedures followed by the employer in ordering the secondment.

This test is notably more stringent than that applied to simple internal reassignments (transfers within the same company), as it explicitly includes scrutiny of personnel selection and procedural fairness. This heightened scrutiny reflects the fact that secondment involves a change in the entity exercising day-to-day command, and the original employer retains a responsibility to ensure fair treatment and protect the employee's contractual rights. Article 14 of Japan's Labor Contract Act now codifies a similar multi-factor test for abuse of secondment orders.

- Application to Secondment Extensions: The Supreme Court applied a similar abuse of rights analysis to the extensions of the secondment period. However, the commentary raises questions about whether the procedural fairness element should be re-evaluated for each extension, and whether the threshold for demonstrating "business necessity" should become higher as the overall duration of a secondment increases, due to the potentially cumulative impact of disadvantages on the employee. There's also a theoretical argument that extremely long secondments might, in substance, become so akin to a permanent transfer that individual consent should arguably be revisited.

Conclusion: Validating Structured Secondments

The Supreme Court's decision in the Steel Company Y (Nippon Steel/Nittetsu Transport No. 2) case affirmed that employers can, under specific conditions, lawfully order employees to undertake long-term secondments to affiliated companies without obtaining fresh individual consent for each assignment. The key legitimizing factors in this case were the pre-existing, detailed provisions in work rules and, particularly, a comprehensive collective agreement (the "External Service Agreement") that permitted such external service for business needs while also providing substantial protections for the status, remuneration, and other working conditions of seconded employees. The ruling also established a robust, multi-faceted test for assessing whether such secondment orders, or their subsequent extensions, constitute an abuse of the employer's managerial rights, balancing genuine business necessities against the potential detriments to the affected employees. This case remains a critical reference point for understanding the legal framework governing employee secondments in Japan, especially in contexts of business restructuring and outsourcing.