Secondary Tax Liability: Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies "Insufficiency of Collection" Requirement

Judgment Date: November 6, 2015

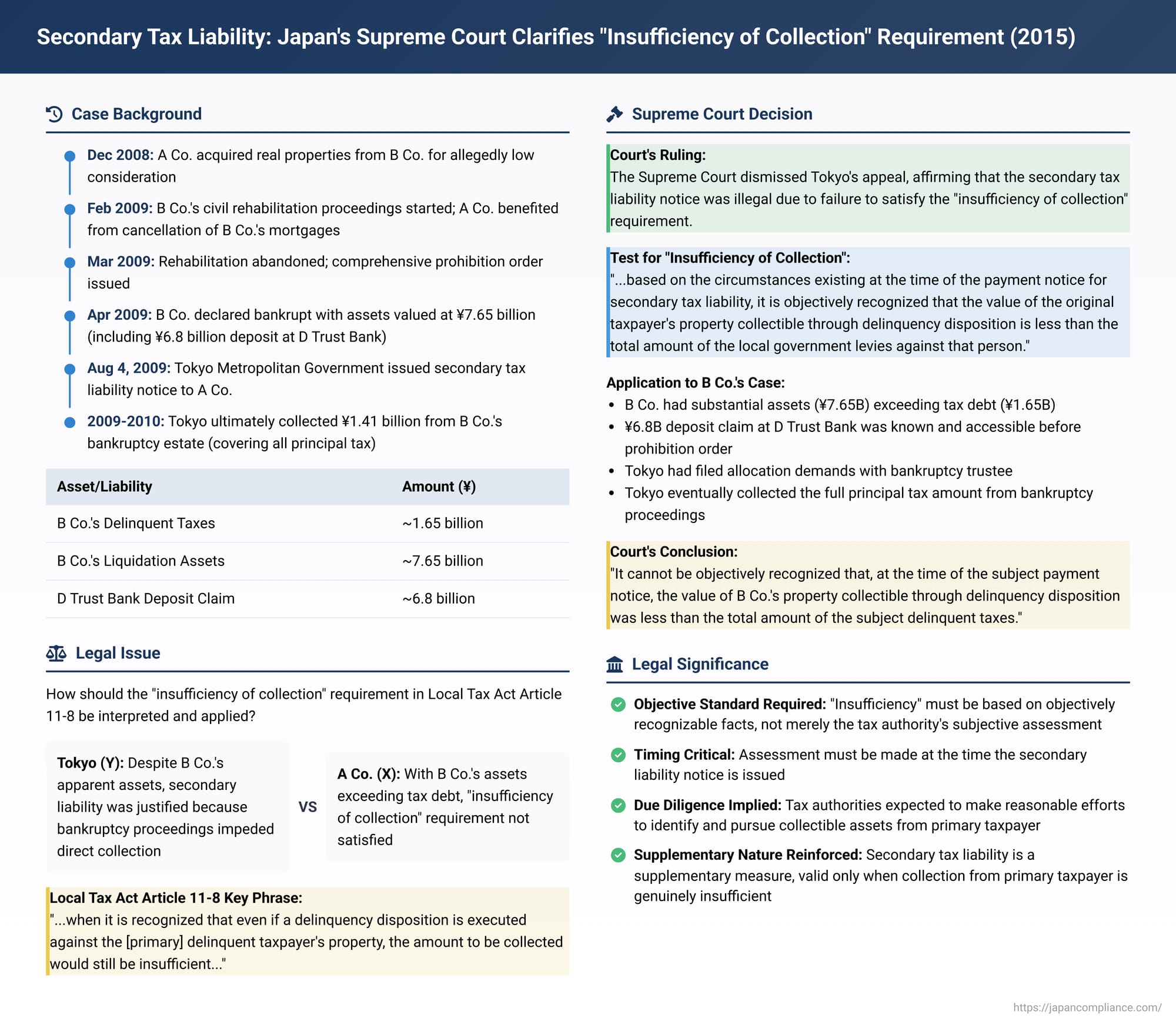

In a significant decision for understanding the prerequisites for imposing secondary tax liability, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan provided a crucial interpretation of the "insufficiency of collection" requirement under local tax law. The case involved the Tokyo Metropolitan Government's attempt to hold a company secondarily liable for the tax debts of another company from which it had acquired assets for allegedly low consideration. The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the lower appellate court's decision to cancel the secondary tax liability notice, agreeing that the tax authority had not adequately established that collection from the primary taxpayer was genuinely insufficient at the time the secondary liability was imposed.

Background: Asset Transfers, Bankruptcy, and Secondary Tax Liability

The dispute centered on "A Co." (which was later acquired by X, the appellee in the Supreme Court), "B Co." (the primary delinquent taxpayer), and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (Y, the appellant).

- Asset Transfers:

- In December 2008, A Co. acquired multiple real properties from B Co. In February 2009, A Co. also benefited from the cancellation of mortgages that B Co. held on several other real properties A Co. had acquired from "C Co. and five other companies."

- The lower courts had determined that these property transfers and mortgage cancellations constituted transfers for "remarkably low consideration" or "dispositions conferring benefit on a third party" as described in Article 11-8 of the Local Tax Act. This article (similar to Article 39 of the National Tax Collection Act) allows tax authorities to impose secondary tax liability on such recipients if the primary taxpayer is delinquent and collection from them is insufficient.

- B Co.'s Financial Decline and Bankruptcy:

- In February 2009, civil rehabilitation proceedings were initiated for B Co.

- However, by March 2009, it became clear that B Co.'s business could not be continued. The rehabilitation proceedings were discontinued, and a comprehensive prohibition order (preventing creditors, including tax authorities, from taking enforcement actions against B Co.'s assets) was issued.

- On April 21, 2009, B Co. was declared bankrupt, and a bankruptcy trustee was appointed to manage its assets.

- Imposition of Secondary Tax Liability on A Co.

- The Tokyo Metropolitan Government (Y) determined that due to B Co.'s aforementioned asset transfers to A Co., even if delinquency dispositions (tax collection enforcement actions) were executed against B Co., the amount collected would be insufficient to cover B Co.'s outstanding metropolitan tax liabilities ("the subject delinquent taxes").

- Consequently, on August 4, 2009, Y issued a "payment notice" (nōfu kokuchi) to A Co. This notice informed A Co. that it was being held secondarily liable for B Co.'s subject delinquent taxes, pursuant to Article 11-8 of the Local Tax Act.

A Co. (and subsequently X, after acquiring A Co. by merger during the appellate stage) challenged this payment notice, initiating administrative appeals and then a lawsuit.

The Core Legal Issue: "Insufficiency of Collection"

The central legal question revolved around the interpretation and application of the phrase in Article 11-8 of the Local Tax Act: "...when it is recognized that even if a delinquency disposition is executed against the [primary] delinquent taxpayer's property, the amount to be collected would still be insufficient..." (「滞納処分をしてもなおその徴収すべき額に不足すると認められる場合」).

This "insufficiency of collection" is a critical prerequisite for imposing secondary tax liability. The dispute was about:

- At what point in time should this "insufficiency" be assessed?

- What standard or method should be used to determine if such "insufficiency" exists?

Lower Court Rulings:

- The Tokyo District Court (first instance) had dismissed A Co.'s claim, thereby upholding the secondary tax liability notice.

- The Tokyo High Court (appellate court) reversed this decision, ruling in favor of A Co. (now X). The High Court held:

- The "insufficiency of collection" must be determined based on the circumstances existing at the time the notice of secondary liability is issued.

- It defined "insufficiency" as a situation where the total estimated value of the primary taxpayer's assets available for seizure is less than the amount of the delinquent tax.

- Crucially, the High Court found that Y (Tokyo) had failed to attempt seizure of a significant asset of B Co. before the comprehensive prohibition order took effect. This asset was a deposit refund claim B Co. held against "D Trust Bank," worth approximately 6.8 billion yen—an amount far exceeding the subject delinquent taxes. The High Court deemed Tokyo's failure to pursue this readily available asset "remarkably unreasonable."

- Therefore, the High Court concluded that the "insufficiency of collection" requirement had not been met, rendering the secondary liability notice illegal.

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government (Y) appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Interpretation of "Insufficiency of Collection"

The Supreme Court dismissed Tokyo's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's conclusion that the secondary liability notice was illegal, although it slightly refined the wording of the test for "insufficiency."

Nature of Secondary Tax Liability

The Court began by explaining the nature of secondary tax liability under Article 11-8 of the Local Tax Act:

"Local Tax Act Article 11-8 imposes secondary tax liability for local government levies owed by a delinquent original taxpayer on a third party who acquired rights or was relieved of obligations due to the original taxpayer making a gratuitous transfer, a transfer for remarkably low consideration, a debt forgiveness, or other disposition conferring benefit on the third party, with respect to the original taxpayer's property, on or after one year prior to the statutory due date of the said local government levies, when it is recognized that, because of such dispositions, even if a delinquency disposition is executed against the original taxpayer, the amount to be collected would still be insufficient. This liability is limited to the extent of the benefit received by the third party that is still existing."

The Court emphasized:

"Thus, considering that the secondary tax liability stipulated in this article is a supplementary obligation imposed on such a third party for the collection shortfall from the original taxpayer..."

Timing and Standard for Assessing "Insufficiency"

Building on this supplementary nature, the Supreme Court defined how to assess the "insufficiency of collection":

"...the phrase 'when it is recognized that even if a delinquency disposition is executed against the delinquent taxpayer's local government levies, the amount to be collected would still be insufficient' as used in the said article is to be interpreted as meaning a case where, based on the circumstances existing at the time of the payment notice for the secondary tax liability, it is objectively recognized that the value of the original taxpayer's property collectible through delinquency disposition (including demands for allocation and participation in seizures) is less than the total amount of the local government levies against that person."

The Supreme Court noted that the timing aspect (assessment at the point of issuing the secondary liability notice) was already fairly established in case law, legal theory, and administrative practice, and was also a premise adopted by both lower courts in this case. The key refinement by the Supreme Court was its emphasis on the need for the insufficiency to be "objectively recognized" rather than based merely on an "estimated value" as the High Court had phrased it. This subtle shift underscores that the determination should not be solely at the tax authority's discretion based on its internal estimates but must be supportable by objective facts.

Application to the Facts of B Co.'s Case

The Supreme Court then applied this standard to the specific financial situation of B Co. at the time A Co. received the secondary liability notice (August 4, 2009):

- Amount of Delinquent Taxes: As of August 4, 2009, B Co.'s total delinquency (principal tax plus delinquency charges) amounted to approximately 1.65 billion yen.

- B Co.'s Known Assets:

- As of April 21, 2009 (when B Co.'s bankruptcy proceedings commenced), B Co. was reported to have assets with a liquidation value of approximately 7.65 billion yen that were not subject to separate security rights (meaning they were potentially available to general creditors, including the tax authority).

- As of October 20, 2009, the balance of B Co.'s bankruptcy estate was approximately 3.79 billion yen.

- Critically, separate from the above, B Co. had, since before the comprehensive prohibition order in March 2009 (and thus before the secondary liability notice to A Co. in August 2009), a deposit refund claim against D Trust Bank worth approximately 6.8 billion yen. This asset was also not subject to separate security rights.

- Stability of Assets Under Bankruptcy Trustee: The Court noted that since B Co.'s assets were under the control of a bankruptcy trustee from April 21, 2009, it was "difficult to conceive that there had been a significant fluctuation in its assets around the time of the subject payment notice" in August 2009.

- Actual Collection Efforts and Recoveries:

- Tokyo (Y) had filed demands for allocation with B Co.'s bankruptcy trustee between June 4 and July 31, 2009, claiming the full delinquent amount as priority claims (zaidan saiken).

- On September 30, 2010, Tokyo received approximately 960 million yen from the bankruptcy trustee as a preferential payment.

- Including this payment, between August 6, 2009, and November 25, 2010, Tokyo collected a total of approximately 1.41 billion yen from B Co.'s assets or its bankruptcy trustee. This amount fully covered the entire principal amount of B Co.'s delinquent taxes.

- The remaining delinquency charges were subsequently recovered by Tokyo through distributions from a separate secured real estate auction related to B Co.

Supreme Court's Conclusion on "Insufficiency"

Based on this factual record, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Considering the above, it cannot be objectively recognized that, at the time of the subject payment notice, the value of B Co.'s property collectible through delinquency disposition (including demands for allocation, etc.) was less than the total amount of the subject delinquent taxes. Therefore, it must be said that the subject payment notice was not made in circumstances that meet the requirement in Article 11-8 of the Local Tax Act of 'when it is recognized that... the amount to be collected would still be insufficient.'"

While the Supreme Court found some aspects of the High Court's reasoning "not necessarily appropriate," it ultimately agreed with the High Court's conclusion that the secondary tax liability notice issued to A Co. was illegal. Tokyo's appeal was therefore dismissed.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This 2015 Supreme Court decision provides important clarifications regarding the "insufficiency of collection" requirement for imposing secondary tax liability:

- Objective Assessment of Insufficiency: The ruling establishes that the determination of whether collection from the primary taxpayer is insufficient must be based on an objective recognition of the facts, not merely the tax authority's subjective estimate or assessment at the time of issuing the secondary liability notice. This potentially places a higher evidentiary burden on tax authorities.

- Timing Remains Critical: The decision affirms the established principle that this objective assessment must be made based on the circumstances existing at the time the secondary liability notice is issued to the third party.

- Thoroughness of Tax Authority's Collection Efforts Implied: While not explicitly stating a due diligence requirement, the facts highlighted by both the High Court and the Supreme Court (particularly the existence of B Co.'s large, unencumbered deposit at D Trust Bank that Tokyo did not initially pursue before B Co.'s financial situation deteriorated further) suggest that tax authorities are expected to have made reasonable efforts to identify and pursue collectible assets from the primary taxpayer before resorting to secondary liability. Failure to do so, or overlooking significant assets, can undermine the claim of "insufficiency."

- Relevance of Post-Notice Information: The Supreme Court's consideration of actual collection amounts received from B Co.'s bankruptcy estate after the secondary liability notice was issued to A Co. indicates that post-notice events can be relevant if they shed light on the objective value of the primary taxpayer's assets as they existed at the time of the notice.

- Reinforcing the Supplementary Nature of Secondary Liability: The judgment strongly reinforces that secondary tax liability is a supplementary measure, to be invoked only when collection from the primary taxpayer is genuinely and objectively insufficient.

This decision underscores the need for tax authorities to make careful and objectively supportable assessments of a primary taxpayer's financial situation and collectible assets before imposing secondary tax liability on third parties. It also provides a clearer standard for courts to review such assessments, emphasizing objective facts over potentially subjective administrative estimations.