Second Chances? How Japan's Supreme Court Views 'Ratification' of an Initially Void Marriage

Date of Judgment: July 25, 1972

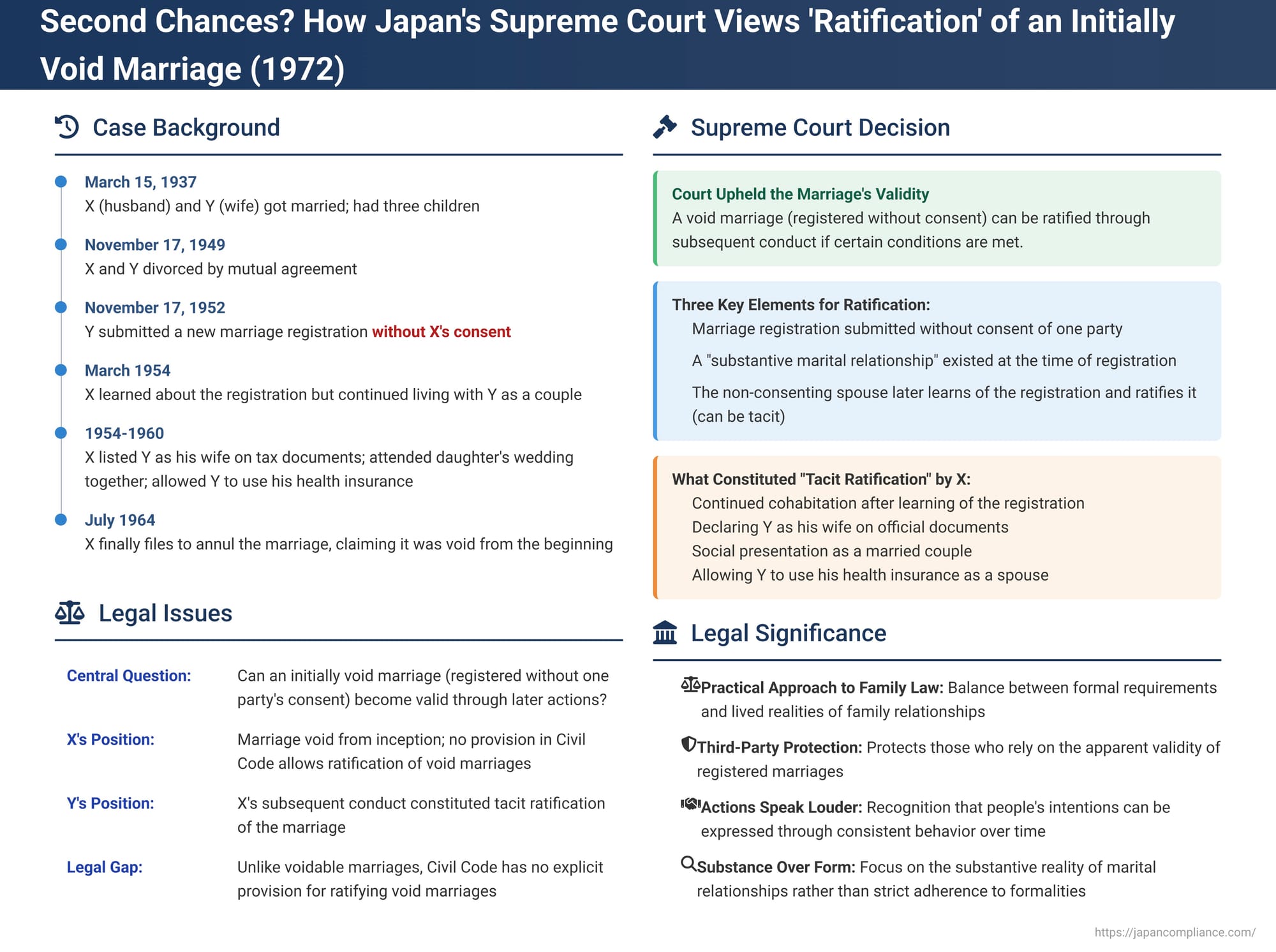

For a marriage to be legally valid in Japan, it generally requires the genuine intent of both parties to marry and the proper submission and acceptance of a marriage registration. But what happens if one party submits this registration without the other's knowledge or consent at that specific time, rendering the marriage initially void? Can such a fundamentally flawed marriage ever become valid? And if so, under what conditions? The Supreme Court of Japan grappled with these intricate questions in a significant decision on July 25, 1972 (Showa 45 (O) No. 238), exploring the possibility of "ratifying" an initially void marriage through subsequent actions and circumstances.

The Case Background: A Marriage, A Divorce, and a Disputed "Remarriage"

The case involved a couple, X (the husband) and Y (the wife), whose marital history was unconventional. They had first married on March 15, 1937, and had three children together: an eldest daughter A, an eldest son B, and a second daughter C. However, this initial marriage ended in an amicable divorce by agreement on November 17, 1949.

The legal dispute centered on a subsequent event. On November 17, 1952, exactly three years after their divorce, Y submitted a new marriage registration form, effectively seeking to remarry X. Years later, X filed a lawsuit to have this second "marriage" declared null and void. He asserted that at the time of this 1952 registration, he possessed no intention to marry Y, nor had he consented to the submission of the marriage registration form. Y contested X's claim, arguing that even if his initial consent was lacking, the marriage had subsequently become valid through his later actions, which amounted to ratification.

A crucial aspect of the case was that despite X's alleged lack of initial consent to the 1952 registration, he and Y had resumed and maintained a de facto marital relationship for a significant period after this second registration was filed and after X became aware of its existence.

The Lower Courts' Findings: A Marriage Validated by Tacit Ratification

The lower courts delved into the complex factual history. They found that Y had indeed submitted the 1952 marriage registration form without X's contemporaneous consent, meaning X's signature and seal were placed on the document and it was filed without his direct involvement or approval at that specific moment. This lack of X's intent to register at the time rendered the 1952 marriage initially void.

However, the lower courts also established several other critical facts:

- At the time Y submitted the 1952 registration, X and Y were already living together in a "substantive marital relationship" (実質的生活関係 - jisshitsu-teki seikatsu kankei).

- X became aware of the 1952 marriage registration around March 1954, approximately 16 months after it was filed.

- Despite learning of the registration, X did not contest its validity at that time. Instead, he continued to live with Y in their de facto marital relationship until they eventually separated around September 1960. He only initiated legal proceedings (mediation) to annul the marriage in July 1964, nearly a decade after becoming aware of the registration.

- During the years between learning of the registration (March 1954) and seeking its annulment (July 1964), X engaged in various actions that were consistent with him being married to Y. These included:

- Listing Y as his wife on official special ward residents' tax declarations.

- Attending their eldest daughter A's wedding reception with Y, presenting themselves as a couple.

- Not raising any objection when a private school teachers' mutual aid association officially recognized Y as his wife.

- Allowing Y to use his mutual aid association member's card, which listed her as his wife, to receive medical treatment.

Based on this pattern of conduct over an extended period after X knew of the registration, the lower courts concluded that X had, at the latest by the time he filed for mediation, given his tacit (implied) ratification (黙示に追認 - mokuji ni tsuinin) to the initially void 1952 marriage. Furthermore, they held that this ratification had a retroactive effect, making the marriage valid from the date of its original registration in 1952. Consequently, X's claim for annulment was dismissed. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding Ratification of a Void Marriage

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions and solidifying the principle that an initially void marriage can, under certain conditions, be validated through subsequent ratification.

The Core Principle Established by the Court:

The Supreme Court articulated a key legal principle: "When one party to a de facto marital relationship prepares and submits a marriage registration without the consent of the other party, if at that time a substantive marital relationship existed between them, and if later the other spouse learns of the registration and ratifies it, it is appropriate to construe that the said marriage becomes valid retroactively to the time of its registration through such ratification."

This means that three conditions are central to this form of ratification:

- The marriage registration was submitted by one de facto spouse without the other's consent at the time of submission.

- A "substantive marital relationship" (a genuine de facto marriage) existed between the parties at the time the flawed registration was made.

- The non-consenting spouse later learns of the registration and subsequently "ratifies" it. This ratification can be tacit (implied by conduct) and does not require any specific legal formality.

Rationale for Allowing Ratification of a Void Marriage:

The Supreme Court provided several justifications for this doctrine:

- Supplements Initial Defect: Ratification by the initially non-consenting party is seen as curing or supplementing the original defect—the lack of their intent for the marriage registration at the moment it was filed.

- Reflects Parties' Intentions and Substantive Reality: Recognizing the validity of the marriage through ratification often aligns with the parties' subsequent intentions as demonstrated by their actions. It also gives legal weight to the substantive reality of their family life, an important consideration in Japanese family law, which tends to value the actual living relationship.

- Protection of Third-Party Reliance: Third parties (such as community members, institutions, and even the children of the relationship) often interact with a couple based on the outward appearance of a marital relationship, which is supported by their cohabitation and the official entry in the family register (戸籍 - koseki). Allowing ratification and retroactive validity minimizes the risk of harm to these third parties who have reasonably relied on the presumed validity of the marriage.

Legal Justification Despite Lack of Explicit Statute:

X argued that there was no specific provision in the Japanese Civil Code allowing for the ratification of a void marriage. The Supreme Court addressed this by reasoning:

- While the Civil Code does not explicitly provide for the ratification of a void marriage, it also does not contain any provision prohibiting it.

- The Code does explicitly permit the ratification of voidable marriages (i.e., marriages with less severe defects, such as those entered into under duress or fraud – see Civil Code Articles 745(2), 747(2)). The Court found it incongruous to allow ratification for voidable marriages but deny it for void ones if reasonable grounds for ratification exist, merely due to the absence of a direct statute for the latter.

- The Court rejected the argument that ratification of void acts is permissible only under Civil Code Article 119 (which deals with the ratification of generally void juristic acts). It drew an analogy to a Supreme Court precedent concerning property law (Showa 37.8.10), where an unauthorized disposition of another person's property (which is void in the sense of not initially producing legal effect) can become retroactively valid if the actual rights holder later ratifies it. This is often understood through an analogy to Article 116 of the Civil Code (effect of ratification of an act by an unauthorized agent). The Court saw a similarity: Y (the de facto wife) had, in a sense, acted without X's authority in a matter concerning his "inherent right" to enter into marriage by submitting the registration. Thus, the spirit of Article 116 could provide a basis for understanding the effect of X's ratification.

- Regarding the argument that ratification should require a formal act, the Court reaffirmed a prior Supreme Court decision (Showa 27.10.3, an adoption case) which established that the ratification of a void status act (like marriage or adoption) does not require any specific formality and can be tacit or implied by conduct.

What Constitutes a "Substantive Marital Relationship" and "Tacit Ratification"?

This ruling hinges on the factual findings of these two key elements:

- Substantive Marital Relationship: The commentary on the case indicates that the lower courts based their finding of a substantive marital relationship on concrete facts such as:

- Cohabitation of X, Y, and their children.

- X providing financial support for living expenses and the children's education, with Y managing the household and raising the children. (These align with spousal duties of cohabitation, cooperation, support, and sharing expenses under Civil Code Articles 752 and 760. )

- The existence of sexual relations between X and Y. (This aligns with assumptions underlying marital fidelity and the presumption of legitimacy of children born during marriage. )

- Recognition by their children and neighbors that X and Y were, in fact, a married couple. (This suggests that societal perception also plays a role. )

The concept is somewhat flexible but generally points to the presence of the functional and social hallmarks of a genuine family life.

- Tacit Ratification: This is an approval or acceptance implied by a person's actions rather than explicit words. In X's case, his conduct over several years after he became aware of the unauthorized 1952 registration—such as consistently identifying Y as his wife in official documents (tax declarations, mutual aid association records for health benefits) and social situations (attending their daughter's wedding together)—was deemed sufficient evidence by the courts to constitute a tacit ratification of the marriage. The existence of the prior substantive relationship might, as the commentary suggests, have somewhat lowered the threshold for inferring an intent to ratify from X's subsequent actions. The fact that X and Y had been previously married could also have been an implicit factor in assessing the situation.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1972 decision on the ratification of a void marriage is a profoundly important judgment in Japanese family law.

- It provides a crucial legal mechanism for an initially void marriage—one flawed at its inception due to a lack of consent to registration by one party—to be "healed" and achieve full, retroactive validity through the subsequent actions and implied consent of that party.

- The ruling demonstrates a pragmatic approach by the judiciary, balancing the strict legal requirements for the formation of marriage with the lived realities of family life and the often-complex intentions of individuals.

- It gives significant weight to the existence of a substantive, de facto marital relationship as a foundational element upon which ratification can operate.

- By allowing for tacit, informal ratification, the Court acknowledged that people's intentions and affirmations can be expressed through consistent conduct over time, not just through explicit declarations or formal legal procedures.

- The decision also takes into account the protection of third parties who may have relied on the outward appearance and official registration of the marriage.

Conclusion: Legal Recognition for Lived Realities

The 1972 Supreme Court ruling on the ratification of an initially void marriage highlights the Japanese legal system's capacity for nuanced and equitable solutions in complex family law matters. It established that where a marriage registration is unilaterally filed by one party but a genuine, functioning family life exists, the subsequent, implied approval of the other party can cure the initial defect and validate the marriage from its inception. This judgment underscores that while legal formalities are important, the law will also look to the substantive realities of relationships and the consistent conduct of individuals to determine the ultimate legal status of a marriage, ensuring that legal outcomes strive to reflect justice and the genuine, albeit sometimes imperfectly expressed, intentions of the parties involved.