Salvaging an Illegal Act: The Supreme Court on "Conversion" in Administrative Law

Date of Judgment: March 2, 2021, Third Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

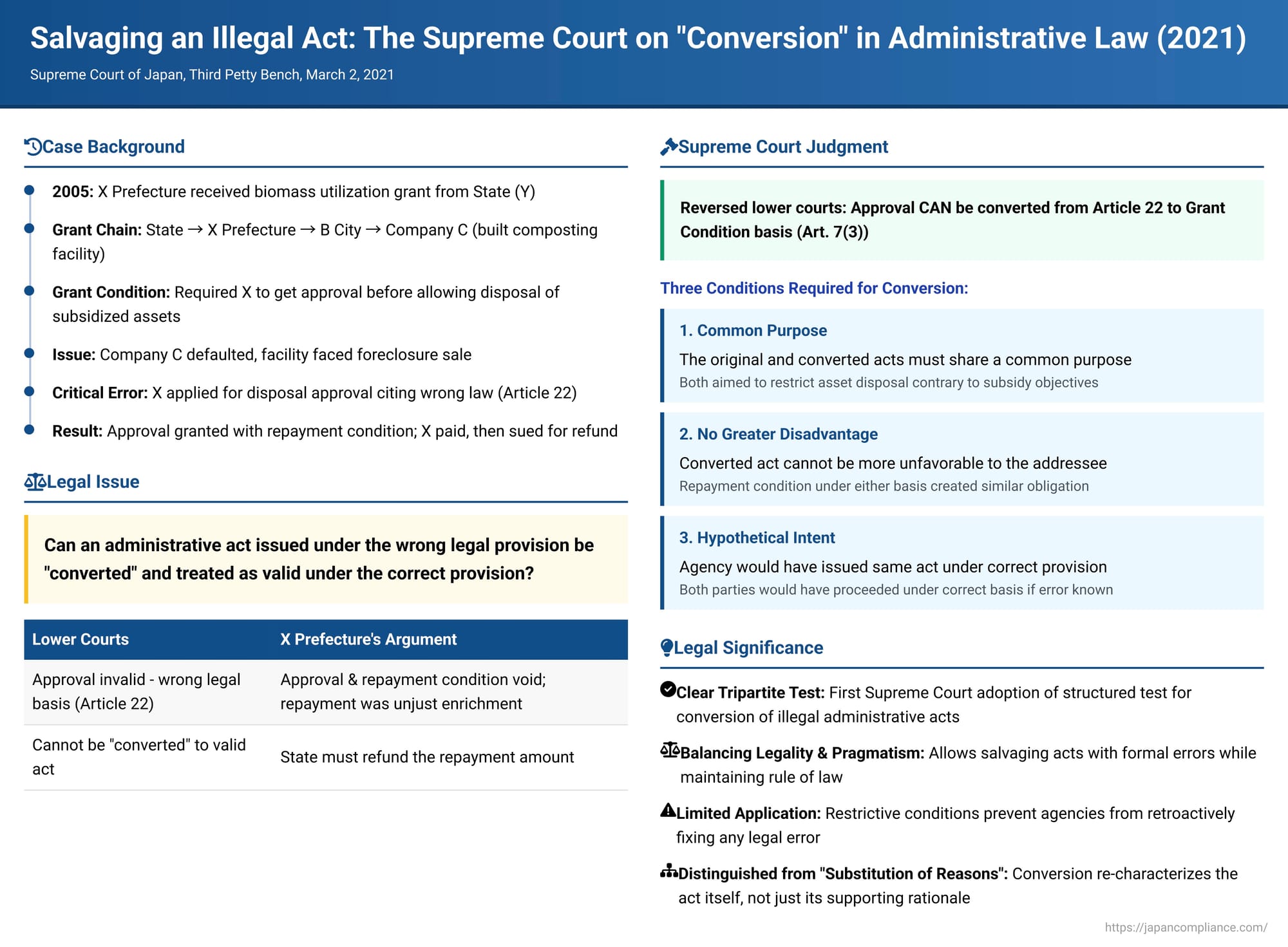

What happens when an administrative agency issues a decision based on an incorrect legal provision? Is the decision automatically invalid, or can it, under certain circumstances, be "saved" by reinterpreting it as a lawful decision under a different, correct legal basis? This complex legal doctrine, known as the "conversion of an illegal administrative act" (違法行為の転換 - ihō kōi no tenkan), was the central focus of a significant Japanese Supreme Court ruling on March 2, 2021. The case, involving a dispute over subsidy repayments, provided a clear articulation of the conditions under which such a conversion is permissible, balancing the principles of legality and administrative pragmatism.

The Factual Background: A Subsidy, a Foreclosure, and a Disputed Repayment

The case involved X Prefecture, which had received a biomass utilization development grant from the State (Y), represented by A, the Director of the Kanto Regional Agricultural Administration Office.

- The Subsidy Scheme: In fiscal year 2005, A made a grant decision (the Grant Decision) to X Prefecture. This Grant Decision included a specific condition (the Grant Condition), based on Article 7, Paragraph 3 of the Act on Optimization of Budget Execution for Subsidies, etc. (hereinafter, the Subsidies Act or the Act). This Grant Condition stipulated that if X Prefecture (the direct subsidy recipient) intended to approve the disposal of any assets acquired by an indirect subsidy recipient using the project funds, X Prefecture first had to obtain prior approval from A (the Director).

X Prefecture subsequently provided a similar subsidy to B City, which in turn provided a subsidy to Company C. Company C used these funds to construct a composting facility (the Facility). - Mortgage, Foreclosure, and Disposal Approval:

- Later, A approved X Prefecture's request to allow Company C to use the Facility as collateral for a loan, and Company C created a mortgage on it.

- Company C eventually ceased operations, and foreclosure proceedings were initiated against the Facility.

- Facing the impending sale of the Facility through foreclosure, X Prefecture applied to A for approval for this "asset disposal". Crucially, X Prefecture's application form stated that the application was being made under Article 22 of the Subsidies Act. Article 22 typically governs the disposal of assets by direct subsidy recipients, not indirect ones like Company C.

- A granted this approval (the Approval) for the disposal of the Facility. However, A attached a condition to this Approval (the Repayment Condition): X Prefecture was required to repay to the State the portion of the original subsidy that corresponded to the national government's contribution to the Facility's disposal price (as determined in the foreclosure sale).

- The Lawsuit: X Prefecture made the repayment as stipulated in the Repayment Condition. However, it then filed a lawsuit against Y (the State) seeking a full refund of this amount, claiming unjust enrichment. X Prefecture argued that the Approval granted by A was without legal basis because Article 22 of the Subsidies Act did not apply to the disposal of assets by an indirect subsidy recipient like Company C. If the Approval itself was legally unfounded, X Prefecture contended, then the attached Repayment Condition was also invalid, and the repayment was made without legal cause.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the Utsunomiya District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (second instance) ruled in favor of X Prefecture. They agreed that Article 22 was indeed the incorrect legal basis for the Approval. They further held that the Approval could not be "converted" into a lawful approval under the correct legal basis (the Grant Condition stemming from Article 7, Paragraph 3 of the Act). Consequently, they found the Approval and the Repayment Condition to be invalid, and ordered the State to refund the money. The State (Y) then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Conundrum: Can an Act Issued Under the Wrong Law Be Saved?

The core issue was whether an administrative act, issued by an agency citing an incorrect or inapplicable legal provision, could nevertheless be considered valid if it could have been lawfully issued under a different, correct legal provision. This is the essence of the doctrine of "conversion of an illegal administrative act." Allowing conversion can promote administrative efficiency and uphold substantive intentions when a formal error is made. However, it also risks undermining the principle of legality (administration by law) and could potentially prejudice affected parties if not strictly controlled.

The Supreme Court's Decision of March 2, 2021

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X Prefecture's claim. It found that the Approval, though ostensibly issued under the incorrect Article 22, could be lawfully "converted" into an approval under the Grant Condition (derived from Article 7, Paragraph 3 of the Subsidies Act), thereby validating the attached Repayment Condition.

The Court meticulously laid out three conditions that must be met for such a conversion to be permissible, drawing upon established legal theory (and, as a supplementary opinion by Justice U noted, principles similar to those in German administrative law ):

1. Common Purpose

The originally intended administrative act (here, an approval for asset disposal purportedly under Article 22) and the potentially valid converted administrative act (an approval under the Grant Condition via Article 7, Paragraph 3) must share a common purpose.

- The Court reasoned that Article 22, which restricts direct subsidy recipients from disposing of subsidized assets without approval, aims to prevent such assets from being used in ways contrary to the original subsidy's objectives.

- Similarly, the Grant Condition (based on Article 7, Paragraph 3), which requires the direct recipient (X Prefecture) to get A's approval before it can approve an indirect recipient's (Company C's) asset disposal, also aims to restrict the disposal of assets acquired through indirect subsidies in a manner contrary to the subsidy's objectives.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that an approval under Article 22 and an approval under the Grant Condition (Article 7, Paragraph 3) "share a common purpose" – ensuring that subsidized assets continue to serve the objectives for which the subsidy was granted.

2. No Greater Disadvantage to the Addressee

The legal effects of the converted administrative act must not be more unfavorable or disadvantageous to the affected party (in this case, X Prefecture) than the original administrative act would have been if it had been flawless (i.e., properly issued under the correct initial basis).

- The Court noted that if a direct subsidy recipient disposes of assets after receiving an Article 22 approval, the original subsidy grant decision is typically not revoked (per Article 17, Paragraph 1 of the Act). Likewise, if an indirect recipient disposes of assets after obtaining approval through the direct recipient under an Article 7, Paragraph 3-based condition, the original Grant Decision to X Prefecture would not be revoked.

- Critically, the Court found that just as an Article 22 approval can be legitimately accompanied by a condition requiring the subsidy recipient to repay all or part of the subsidy, an approval based on an Article 7, Paragraph 3 condition can also legitimately include a similar repayment condition for the direct recipient (X Prefecture). This is especially so because if such approval for disposal were not obtained, the entire original Grant Decision could potentially be revoked, leading to a full demand for repayment.

- Thus, treating the Approval (nominally under Article 22) as if it were made under the Grant Condition (Article 7, Paragraph 3), with a similar repayment requirement, would not place X Prefecture in a worse position.

3. Hypothetical Intent of the Agency (and Awareness of the Applicant)

It must be presumable that the administrative agency (A, the Director) would have issued the converted administrative act had it been aware of the flaw in the original act (i.e., the inapplicability of Article 22). Furthermore, it should not appear that the applicant would have refused or not sought this converted act.

- The Court found no evidence to suggest that if A and X Prefecture had realized that an approval under Article 22 was inappropriate, they would have refrained from seeking and granting an approval under the Grant Condition (Article 7, Paragraph 3), given that both routes served the same underlying purpose of regulating asset disposal.

- A supplementary opinion by Justice U further noted that X Prefecture itself had, in its own regulations for passing on subsidies, provisions mirroring the conditions imposed by the State, suggesting an awareness and acceptance of such regulatory mechanisms. This supported the inference that both parties would have proceeded under the correct legal basis had the initial error been identified.

Because all three conditions were met, the Supreme Court concluded that the Approval granted by A, along with the Repayment Condition, was legally valid as if it had been correctly issued under the Grant Condition (Article 7, Paragraph 3 of the Subsidies Act) from the outset. Therefore, X Prefecture's repayment was based on a valid legal obligation, and its claim for unjust enrichment failed.

Key Takeaways and Analysis

This 2021 Supreme Court judgment is highly significant for providing a clear and structured articulation of the requirements for the "conversion of an illegal administrative act."

1. Formal Endorsement of a Tripartite Test for Conversion:

The decision formally adopts a three-pronged test (common purpose, no greater disadvantage, and hypothetical intent) that aligns closely with established legal theory, including principles found in comparative administrative law (e.g., German Federal Administrative Procedure Act, § 47). This brings greater clarity and predictability to a complex legal doctrine.

2. Balancing Legality with Administrative Pragmatism:

The doctrine of conversion allows administrative actions to be salvaged when a formal error in citing the legal basis occurs, provided the substantive outcome is one that could have been lawfully achieved and no prejudice results to the affected party. This promotes administrative efficiency and avoids the need for potentially duplicative processes, but it is carefully circumscribed by the three conditions to uphold the rule of law.

3. Distinction from "Substitution of Reasons":

"Conversion" is distinct from "substitution of reasons" (理由の差替え - riyū no sashikae). Substitution involves an agency attempting to justify an administrative act with different factual or legal arguments during litigation, without changing the essential nature or legal characterization of the act itself. Conversion, however, involves re-characterizing the illegal act as a different type of lawful administrative act. Because conversion can alter the act's legal content and effect, it requires a more stringent set of conditions, including the "no greater disadvantage" and "hypothetical intent" elements, which are not typically central to substitution of reasons.

4. Importance of Procedural Fairness and Third-Party Rights:

While this particular case primarily involved the relationship between the granting agency and the direct subsidy recipient, the supplementary judicial opinion highlighted that the conditions for conversion are necessary but may not always be sufficient. For instance, if the converted act would normally require specific procedural steps (like a hearing or consultation with an expert body) that were not undertaken for the original flawed act, conversion might be problematic. Similarly, if converting the act would adversely affect the rights or legitimate expectations of third parties, that would also need careful consideration. In this case, such complicating factors were not found to be present.

5. Limited Scope and Strict Application:

The doctrine of conversion is intended to be applied restrictively. It is not a general license for agencies to retroactively fix any legal error. The conditions, particularly the commonality of purpose and the absence of detriment to the addressee, must be clearly met. The aim is to allow for a common-sense rectification of formal errors where the substance of the administrative goal remains legitimate and achievable through an alternative, correct legal path, without unfairness.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2021 decision provides a valuable and clear framework for understanding the "conversion of illegal administrative acts" in Japanese law. By establishing explicit conditions based on common purpose, absence of disadvantage, and hypothetical intent, the Court has offered a principled approach to a doctrine that seeks to reconcile administrative pragmatism with the fundamental requirements of legality and fairness. This ruling will undoubtedly serve as important guidance for future cases where the legal basis of an administrative action is challenged, ensuring that any "conversion" is carefully considered and strictly limited to appropriate circumstances.