Sale with Repurchase or Disguised Loan? Japanese Supreme Court on True Intent in Property Transactions

Date of Judgment: February 7, 2006

Case Name: Claim for Vacant Possession of Building

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

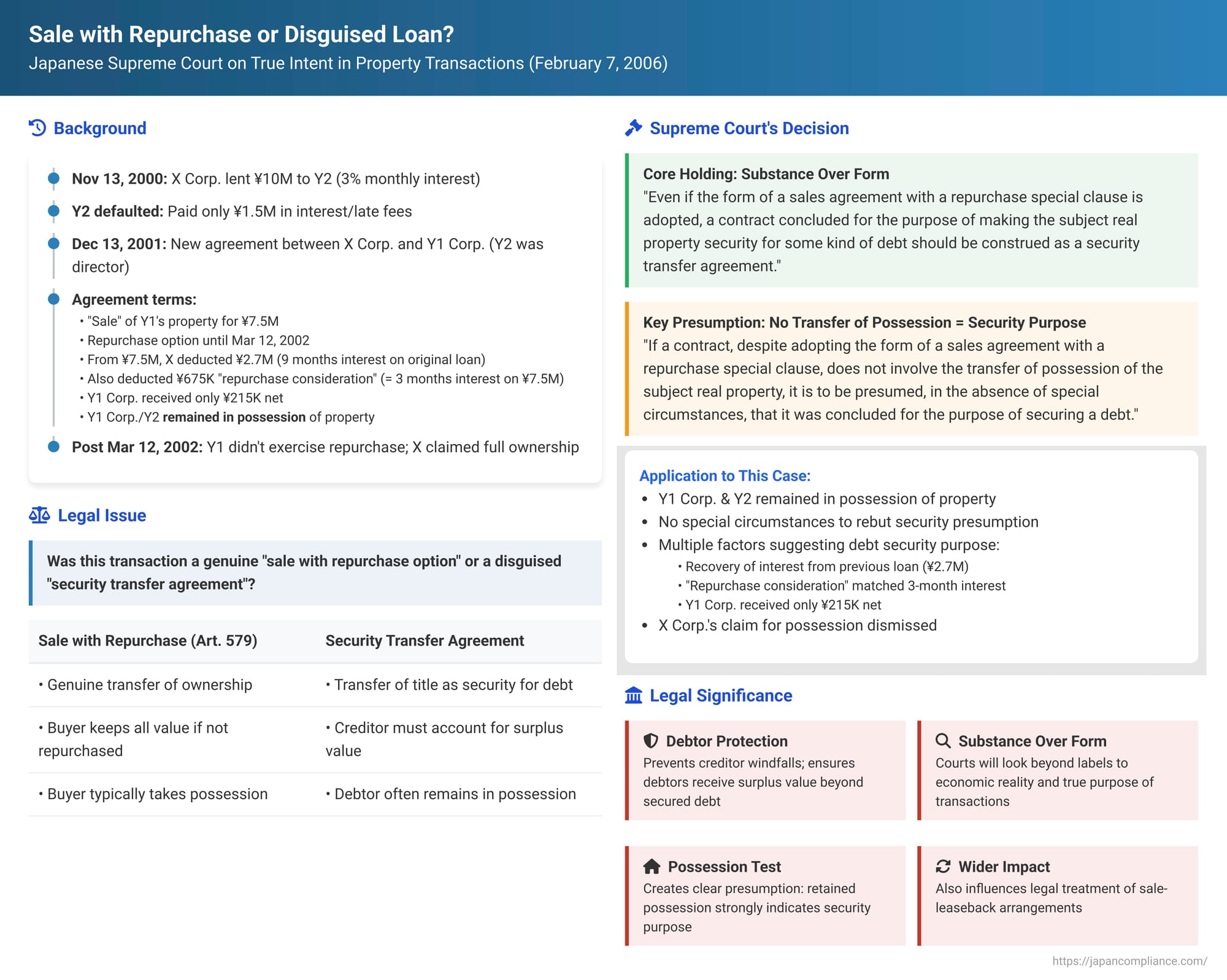

Parties in financial distress sometimes enter into property transactions that, while appearing as straightforward sales, might in substance be disguised secured loans. One such form is a "sale with a repurchase special clause" (kaimodoshi tokuyaku-tsuki baibai keiyaku), a mechanism provided for in the Japanese Civil Code (Article 579 et seq.). This allows a seller to sell property but retain an option to buy it back within a specified period by returning the sale price and contract costs. However, if the economic reality of such an agreement is primarily to provide security for a debt rather than effect a genuine sale, Japanese courts may look beyond the formal label. The Supreme Court of Japan, in a significant judgment on February 7, 2006, provided crucial clarification on when such an agreement should be recharacterized as a "security transfer agreement" (jōto tanpo keiyaku), subjecting it to different legal rules, particularly concerning debtor protection.

The Factual Background: A Loan, a Default, and a Disputed "Sale"

The case involved X Corp., a lender, and Y1 Corp. (represented by its director, Y2), which owned certain real property. The dispute arose from an agreement concerning Y1 Corp.'s property, an agreement that followed Y2's default on a separate, pre-existing loan from X Corp.

- The Separate Loan and Default: On November 13, 2000, X Corp. had lent ¥10 million to Y2 personally. This loan carried a high monthly interest rate of 3%. It was secured by a security transfer agreement (jōto tanpo keiyaku) over property owned by a different entity, Non-party A Corp.. Y2 made only five interest and late fee payments on this "Separate Loan," totaling ¥1.5 million, and then defaulted on further payments.

- "This Agreement" – The Disputed Transaction: To recover at least the outstanding interest on this defaulted Separate Loan, X Corp. entered into a new agreement on December 13, 2001, this time with Y1 Corp. (of which Y2 was the representative director). This agreement concerned land and a building owned by Y1 Corp. (referred to as "the Property"). The agreement was formally titled a "Land and Building Sales Agreement with Repurchase Special Clause".

- Terms of "This Agreement":

- The "sale price" for the Property was set at ¥7.5 million (¥6.5 million for the land, ¥1 million for the building).

- Y1 Corp. was given a repurchase period ending March 12, 2002, within which it could buy back the Property.

- From the ¥7.5 million "sale price," several amounts were deducted upfront: ¥2.7 million, explicitly stated as nine months' worth of outstanding interest on Y2's ¥10 million Separate Loan (at 3% per month); ¥675,000, described as "consideration for granting the repurchase right," which notably matched three months' interest at 3% per month on the ¥7.5 million "sale price"; and other costs including registration fees, totaling ¥3,785,000.

- The net amount actually delivered to Y1 Corp. after these deductions was only ¥215,000 (though the transaction was structured to show the full ¥7.5 million as notionally paid and received in stages).

- Possession Retained by Seller: A critical fact was that "This Agreement" did not stipulate for the transfer of possession of the Property from Y1 Corp. to X Corp. during the repurchase period. Y1 Corp. and Y2 continued to occupy and use the Property even after the agreement date.

- Registration: The transaction was registered in accordance with its form as a sale with a repurchase option.

- Terms of "This Agreement":

- X Corp.'s Lawsuit: Y1 Corp. did not exercise its option to repurchase the Property by the March 12, 2002 deadline. X Corp. then filed a lawsuit against Y1 Corp. and Y2, claiming that it had acquired full ownership of the Building due to the lapse of the repurchase option and demanding vacant possession. Y1 Corp. and Y2 defended the claim by arguing that "This Agreement" was not a genuine sale with a repurchase option but was, in substance, a security transfer agreement designed to secure Y2's debts. If it was a security transfer, X Corp. would not automatically become the outright owner upon the lapse of the "repurchase" period but would be subject to obligations such as accounting for any surplus value (settlement - seisan).

Lower Courts: A True Sale with Repurchase Option

The District Court and subsequently the High Court both ruled in favor of X Corp.. They found "This Agreement" to be a genuine sale with a repurchase option, not a disguised security transfer. Their reasoning included points such as:

- The difference in titles: the document for the Separate Loan's security was explicitly titled a "Security Transfer Agreement with Repurchase Clause," whereas the document for "This Agreement" was titled a "Land and Building Sales Agreement with Repurchase Clause".

- The ¥675,000 deducted as "consideration for the repurchase right" was not, in their view, proven to be consideration (interest) for a loan made under "This Agreement" itself.

- They found insufficient evidence to support Y1 Corp.'s claim that the Property's market value was substantially higher (e.g., ¥18 million or more, as alleged by Y1/Y2), which might have suggested the "sale price" was disproportionately low and indicative of a loan rather than a true sale.

Y1 Corp. and Y2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal (February 7, 2006): Substance Over Form

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X Corp.'s claim for possession. The Court emphasized a substance-over-form approach in determining the true nature of such transactions.

1. Debt Security Purpose Transforms "Sale with Repurchase" into "Security Transfer":

The Court laid down a clear principle:

- In a genuine sale with a repurchase option under the Civil Code, if the seller fails to return the purchase price and contract costs within the stipulated repurchase period, they lose the right to get the property back. Even if the property's actual market value significantly exceeds the repurchase price (i.e., the original sale price plus costs), the buyer is not obligated to pay any surplus to the seller. This potential for the "buyer" (creditor) to obtain a windfall is a key characteristic of a true repurchase agreement but is contrary to the principles governing security interests.

- In contrast, a security transfer agreement requires the secured creditor, upon enforcement, to account for the property's value and return any surplus over the secured debt to the debtor (this is the duty of settlement of accounts - seisan gimu, affirmed in cases like Supreme Court, March 25, 1971, Minshū Vol. 25, No. 2, p. 208, the "M94 case").

- The Supreme Court therefore ruled: "Such effects [i.e., the buyer retaining all surplus value] cannot be recognized if the said contract has the purpose of securing a debt. Even if the form of a sales agreement with a repurchase special clause is adopted, a contract concluded for the purpose of making the subject real property security for some kind of debt should be construed as a security transfer agreement."

2. Presumption Arising from Seller Retaining Possession:

The Court then established an important evidentiary presumption:

- A genuine sale with a repurchase option normally involves the transfer of possession of the property from the seller to the buyer. The Civil Code itself (Article 579, latter part, which deems fruits of the property and interest on the price to be set off if repurchase occurs) implicitly assumes such a transfer of possession.

- Therefore, the Court held: "If a contract, despite adopting the form of a sales agreement with a repurchase special clause, does not involve the transfer of possession of the subject real property, it is to be presumed, in the absence of special circumstances, that it was concluded for the purpose of securing a debt, and its nature should be reasonably construed as a security transfer agreement."

3. Application to the Facts of This Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:

- "This Agreement" clearly did not involve the transfer of possession of the Property from Y1 Corp. to X Corp.; Y1 Corp. and Y2 continued to occupy it.

- There were no "special circumstances" presented that could rebut the presumption that this arrangement was for debt security.

- On the contrary, several facts strongly indicated a debt security purpose:

- X Corp.'s primary motivation for entering into "This Agreement" was to recover at least the overdue interest from Y2's Separate Loan. Indeed, ¥2.7 million, corresponding to nine months' interest on the original ¥10 million Separate Loan, was deducted from the purported ¥7.5 million "sale price" of the Property.

- The ¥675,000 deducted as "consideration for granting the repurchase right" was exactly equivalent to three months' interest (at the same 3% monthly rate) on the ¥7.5 million "sale price." For Y1 Corp. to repurchase, it would have had to repay not just the ¥7.5 million and contract costs, but effectively this additional sum as well, which strongly suggested it was interest on a loan secured by "This Agreement". (A true repurchase under the Civil Code requires only the return of the original price plus contract expenses, not an extra payment for the option itself that functions like interest ).

- Conclusion: Given these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that "This Agreement" was not a genuine sale with a repurchase option but was, in substance, a security transfer agreement. Therefore, X Corp.'s claim for vacant possession, which was predicated on it having acquired outright ownership through a lapsed repurchase option under a genuine sale, was unfounded and should be dismissed.

Distinguishing True Sales with Repurchase from Security Transfers

This judgment by the Supreme Court effectively prioritizes the economic substance of a transaction over its formal label, particularly when debt security is the underlying purpose.

- True Sale with Repurchase (Civil Code Art. 579 ff.): This is a specific type of sale where the seller reserves the right to unilaterally cancel the sale and reacquire the property by returning the purchase price and contract costs within a specified period (not exceeding ten years). If the seller fails to do so, the buyer's ownership becomes absolute. The key is that it's intended as a genuine, albeit conditional, transfer of ownership, not primarily as a loan secured by the property. The "buyer" in such a transaction is not obligated to return any surplus if the property's value far exceeds the repurchase price.

- Security Transfer (Jōto Tanpo): This is a judicially developed form of non-statutory security interest in Japan where formal title to an asset (movable or immovable) is transferred to a creditor to secure a debt. However, the economic ownership effectively remains with the debtor. If the debtor repays the debt, title is returned. If the debtor defaults, the creditor can enforce the security, typically by selling the asset or, in some forms (like "attributive settlement" - kisoku seisan), by taking full ownership. Crucially, if the property's value exceeds the debt, the creditor has a duty to account for and return the surplus to the debtor (seisan gimu). The debtor also typically retains a right of redemption (ukemodoshi-ken) until this settlement process is completed.

The Supreme Court's 2006 ruling effectively states that if a transaction cast in the form of a "sale with repurchase option" is found to have the underlying purpose of securing a debt, it will be recharacterized as a "security transfer" and subjected to the rules and debtor protections applicable to security transfers, most notably the creditor's duty of settlement. This prevents creditors from using the repurchase form to achieve a forfeiture of the collateral (a "creditor windfall") that would not be permitted under security transfer law.

The Significance of Retained Possession

The Supreme Court's establishment of a presumption that a sale with repurchase option is for debt security if the seller retains possession is a highly significant aspect of this judgment.

- Previously, lower courts often placed the full burden on the seller (debtor) to prove that such a transaction was for security, considering a range of factors on a case-by-case basis.

- The presumption based on non-transfer of possession provides a strong starting point for analysis. If the party nominally selling the property (but actually providing it as security) remains in possession, it strongly suggests that a true sale (which normally involves the buyer taking control) was not intended.

- This does not mean the presumption is irrebuttable. The Court allowed for "special circumstances" that could demonstrate it was a genuine sale despite retained possession. Conversely, even if possession is transferred to the "buyer," the "seller" can still attempt to prove that the transaction was, in substance, for debt security purposes, though the presumption would not aid them in that scenario.

Impact of the Ruling

This judgment has several important implications:

- Enhanced Debtor Protection: It significantly strengthens protections for debtors who might enter into such agreements under financial pressure, ensuring they are entitled to any surplus value in their property beyond the secured debt.

- Substance Over Form: It reinforces the judiciary's commitment to looking at the economic reality and purpose of a transaction rather than being bound by its formal label.

- Clarity for Practitioners: It provides a clearer (though not absolute) guideline – the retention of possession by the seller – for assessing whether a sale with repurchase option is likely to be treated as a security transfer.

- Relevance to "Leaseback" Arrangements: Legal commentary notes that the reasoning in this judgment is also influential in how courts approach "sale-and-leaseback" arrangements used for financing. If a party sells an asset and immediately leases it back from the buyer, this too can be recharacterized as a security transfer if the overall transaction is essentially a loan secured by the asset, with the "rent" payments being disguised loan repayments.

It's also worth noting that minor textual amendments were made to Civil Code Articles 579 and 581 in the 2017 Civil Code reforms (effective 2020), but these changes do not affect the fundamental principles laid down in this 2006 Supreme Court judgment.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of February 7, 2006, is a critical precedent in the law of secured transactions. It firmly establishes that agreements structured as "sales with a repurchase special clause" will be treated as "security transfer agreements" if their underlying purpose is to secure a debt. The presumption that such a security purpose exists if the seller retains possession of the property provides a powerful tool for courts to look beyond the form and ensure that debtor protection mechanisms, particularly the creditor's duty to account for surplus value, are not circumvented. This ruling champions a substance-over-form approach, promoting fairness in financial transactions and discouraging disguised lending practices that could unduly disadvantage borrowers.