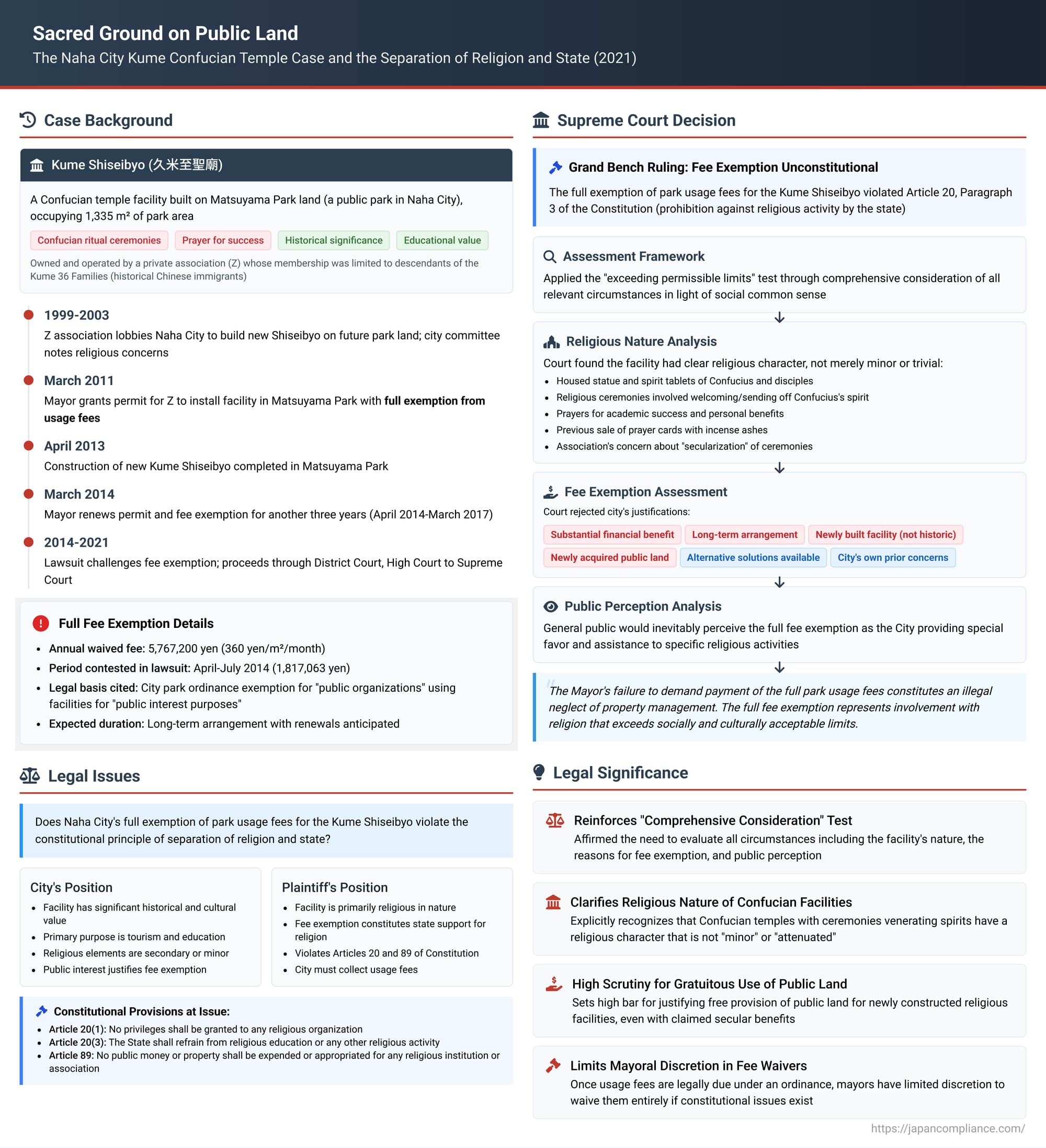

Sacred Ground on Public Land: The Naha City Kume Confucian Temple Case and the Separation of Religion and State

Date of Judgment: February 24, 2021

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench, 2019 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 222, 2019 (Gyo-Hi) No. 262

Introduction

On February 24, 2021, the Supreme Court of Japan's Grand Bench delivered a landmark ruling on the constitutional principle of separation of religion and state. The case concerned Naha City's decision to allow a private association to build and operate a Confucian temple, the Kume Shiseibyo, on public park land free of charge. Residents challenged this arrangement, arguing that the full exemption from park usage fees constituted an impermissible entanglement of the state with religion. The Supreme Court, in a detailed judgment, found the city's actions unconstitutional, providing significant clarification on how the "purpose and effect" test and a broader "comprehensive consideration of circumstances" are applied in such cases. This decision has important implications for local governments across Japan regarding the use of public property for facilities with religious associations.

Factual Background: The Kume Shiseibyo in Matsuyama Park

The case revolved around the Kume Shiseibyo (久米至聖廟 - Kume Shiseibyō), a facility dedicated to Confucius and his principal disciples, located within Matsuyama Park, a public park managed by Naha City, Okinawa Prefecture.

- The Facility and Its Operating Entity:

- The Kume Shiseibyo (referred to as "the Facility") was installed on public land within Matsuyama Park. It comprised several structures, including the Taisen-den (main hall), Keisei-shi (a shrine), Meirin-do (a hall for learning, also serving as a library), and the Shisei-mon (main gate), occupying an area of 1,335 square meters. The site was fenced off from other parts of the park.

- The Facility was owned and operated by Z (the intervener in the lawsuit), a general incorporated association. Z's stated purposes included the public display of the Facility, historical research related to the "Kume Sanjussei" (久米三十六姓 - 36 Kume Families, descendants of Chinese immigrants who played significant roles in the Ryukyu Kingdom from the 14th to 17th centuries), and the promotion of Eastern culture centered on the Analects of Confucius. Membership in Z was restricted by its articles of association to descendants of these Kume families.

- The Taisen-den, considered the main hall, housed a statue of Confucius and spirit tablets of Confucius and his four chief disciples (the Shihai). It attracted numerous visitors, including those praying for family prosperity, academic success, and success in examinations. At one point, "academic achievement (prayer) cards," containing ashes from the Taisen-den's incense burner, were sold at the Facility.

- A significant annual event at the Facility was the Sekiten Sairei (釋奠祭禮), a Confucian memorial ceremony held on Confucius's birthday (September 28th). This ceremony involved offering food and drink, burning incense, and reading eulogies to welcome and send off the spirit of Confucius. Z's articles of association explicitly listed the performance of the Sekiten Sairei as one of its activities, and Z maintained that allowing non-descendants of the Kume families to conduct it would risk its secularization or transformation into a tourist show, which was unacceptable.

- Historical Lineage:

- The original Shiseibyo and an associated school, the Meirin-do (the first public school in Ryukyu), were established by the Kume Sanjussei in the Kume district of Naha in the 17th and 18th centuries.

- After the Meiji Restoration and the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in 1879, these facilities and their land were nationalized, then returned to Naha Ward, and in 1915, granted to Z's predecessor, the Kume Soseikai. The original facilities were subject to regulations similar to those for shrines and temples.

- The original Shiseibyo and Meirin-do were destroyed during World War II. They were later rebuilt by Z around 1974-1975 on land owned by Z in Wakasa, Naha, along with a Taoist temple (Tensonbyo) and a sea goddess shrine (Tenpikou). Z's publications indicated that these combined facilities in Wakasa received about 200 visitors per day.

- Relocation to Matsuyama Park and Fee Exemption:

- In 1999, Z learned that Naha City was acquiring the site of the former Kume Post Office, adjacent to Matsuyama Park, to incorporate it into the park. Z began lobbying the City in 2000 to relocate the Shiseibyo to this new park area, seeking a "return" to the Kume district (though not its exact original location).

- In 2003, a Naha City committee discussing the land use plan for the Matsuyama Park area noted concerns about the religious nature of the Shiseibyo. The City's draft plan suggested that constructing such a facility on public land or with public subsidies would be problematic and proposed considering a land swap to place it on private land.

- Despite this, in 2006, the City acquired the former post office site (from the national government) and also entered into a free lease agreement for adjacent national land to expand Matsuyama Park.

- In March 2011, the then-Mayor of Naha City, based on Z's application, granted a permit for Z to install the Facility in Matsuyama Park for a period of three years (until March 31, 2014). Crucially, the Mayor also granted a full exemption from park usage fees for this period. The Naha City Park Ordinance allowed the Mayor to fully exempt "public organizations" using park facilities for "public interest purposes" (Article 11-2, Item 4, and Park Ordinance Enforcement Rules Article 15, Paragraph 1, Item 2), or to exempt fees to an extent the Mayor deemed necessary in other "specially necessary" cases (Ordinance Art. 11-2, Item 8; Rules Art. 15, Para. 1, Item 3). The full annual usage fee for the occupied area (1335 sqm at 360 yen/sqm/month) would have been 5,767,200 yen.

- Z constructed the new Facility, completing it by April 2013.

- Upon the expiry of the initial permit, in March 2014, the then-Mayor renewed Z's park facility installation permit for another three years (April 1, 2014, to March 31, 2017) and again granted a full exemption from usage fees ("the Exemption" - 本件免除 - honken menjo) for this period, based on the same "public organization for public interest" provision. This renewal was expected to continue as long as it did not impede park management.

- The Lawsuit:

X, a resident of Naha City (the first-instance plaintiff), filed a resident lawsuit arguing that the Mayor's act of granting the full fee exemption was an unconstitutional violation of the separation of religion and state and therefore void. X claimed that the current Mayor Y's failure to collect park usage fees from Z for the period April 1, 2014, to July 24, 2014 (amounting to 1,817,063 yen – "the Usage Fee in Question" or 本件使用料 - honken shiyoryo) constituted an illegal neglect of property management. The suit sought a declaration of this illegality under LAA Article 242-2, Paragraph 1, Item 3.

Lower Court Rulings

- The Naha District Court (second first-instance ruling) found in favor of X, declaring the Mayor's failure to collect the full Usage Fee in Question illegal. It held that the fee exemption violated the constitutional principle of separation of religion and state.

- The Fukuoka High Court, Naha Branch (second appellate ruling) partially upheld the plaintiff's claim. While agreeing that the fee exemption was unconstitutional, it modified the first-instance ruling. It stated that a failure to collect the entire fee was not immediately illegal, implying that a partial exemption reflecting any secular public benefit (e.g., tourism, cultural value) might be permissible. However, it did not quantify this permissible partial exemption, but still found an illegal omission in not collecting at least some portion of the fees.

Both Z (the association) and X (the resident plaintiff) appealed aspects of the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, which consolidated the appeals and referred them to the Grand Bench.

The Supreme Court's (Grand Bench) Judgment and Rationale

The Supreme Court Grand Bench delivered a complex judgment that ultimately found the full fee exemption unconstitutional and the Mayor's failure to collect the fees illegal.

1. Constitutional Framework for Separation of Religion and State

The Court began by reiterating its established framework for analyzing cases involving the separation of religion and state, as defined by Articles 20(1) (latter part), 20(3), and 89 of the Constitution:

- Core Principle: The principle of separation of religion and state signifies the non-religious nature or religious neutrality of the State (including local public entities).

- Not Absolute Prohibition: It does not prohibit any and all forms of contact between the State and religion.

- The "Exceeding Permissible Limits" Test: The constitutional provisions are violated when the State's involvement with religion, viewed in light of Japan's social and cultural conditions and in relation to the fundamental constitutional objective of securing freedom of religion, is found to exceed reasonable or socially acceptable limits.

- Comprehensive Assessment for Use of Public Property: Specifically, when a local government exempts usage fees for public land used for a facility, the constitutionality of this action is to be determined by a comprehensive assessment, based on social common sense, of all relevant circumstances. These include:

- The nature of the facility in question.

- The background and reasons for granting the fee exemption.

- The manner and extent of the gratuitous provision of public land resulting from the exemption.

- The general public's perception of these arrangements.

The Court cited its four major Grand Bench precedents on this issue (Tsu City Jichinsai case, Ehime Prefecture Tamagushiryo case, and the two Sunagawa City Shrine land cases) as the basis for this approach.

2. Application to the Kume Shiseibyo Fee Exemption

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to the facts of the Naha City case:

- Religious Nature of the Facility:

- The Taisen-den (main hall) is configured with a statue of Confucius and spirit tablets of Confucius and his four disciples, and it receives many visitors who engage in prayerful acts for various personal benefits. The past sale of "academic achievement prayer cards" further indicated a religious dimension.

- The Sekiten Sairei ceremony involves welcoming and sending off the spirit of Confucius with offerings and prayers. This goes beyond merely honoring a historical figure and constitutes a ritual with religious significance, premised on the existence of Confucius's spirit. Z's explicit rejection of secularizing this ceremony underscores its religious importance to the association.

- The physical layout of the Facility, with the Shisei-mon's central door reserved for Confucius's spirit and the processional path (御路 - mi-roji) leading to the Taisen-den, is designed to serve this religious ceremony.

- The historical lineage, with the original Shiseibyo being treated similarly to shrines and temples and the current Facility being its successor, further supports its religious character.

- Conclusion on Religious Nature: The Facility as a whole possesses a religious character, and this religious nature is not insignificant or merely trivial.

- Circumstances of the Fee Exemption:

- The City argued that the exemption was justified by the Facility's value as a tourist attraction and its historical significance (related to the Kume Sanjussei and Ryukyuan history).

- However, the Court noted that the land in question was newly acquired by the City for park purposes. Z already owned the previous Shiseibyo site. The City's own earlier land use plan had identified the religious nature of the proposed facility as problematic for location on public land and had suggested private land alternatives.

- The current Facility was newly constructed in 2013 and was not a restoration of an ancient monument on its original site, nor did it have any official designation as a cultural property.

- Therefore, the asserted secular benefits (tourism, historical value) did not, in the Court's view, sufficiently establish the necessity or reasonableness of providing newly acquired public parkland entirely free of charge for this particular facility.

- Manner of Gratuitous Provision and Public Perception:

- The area occupied (1335 sqm) was substantial, and the waived annual fee (over 5.76 million yen) represented a significant financial benefit to Z.

- The arrangement was intended to be long-term, with renewals expected as long as the Facility existed and did not hinder park management.

- Z, while having historical research and cultural promotion as stated aims, also clearly listed the public display of the religiously significant Facility and the performance of the religious Sekiten Sairei as core purposes and activities.

- Given these factors, the Court concluded that the full fee exemption, by bestowing such a significant and ongoing benefit, would inevitably lead the general public to perceive that the City was providing special favor and assistance to the specific religious activities associated with Z and the Kume Shiseibyo.

- Constitutional Violation:

Considering all these circumstances comprehensively and in light of social common sense, the Supreme Court held that the City's fee exemption for the Kume Shiseibyo represented an involvement with religion that exceeded the socially and culturally acceptable limits, viewed in relation to the constitutional aim of ensuring freedom of religion. Therefore, the Exemption constituted "religious activity" by the City prohibited under Article 20, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution. Having found a violation of this provision, the Court deemed it unnecessary to make separate findings on potential violations of Article 20, Paragraph 1 (latter part - prohibition of privileges to religious groups) or Article 89 (prohibition of public expenditure for religious organizations). The fee exemption was thus unconstitutional and void.

3. Illegality of Failing to Collect Usage Fees

Since the Mayor's act of granting the full fee exemption was unconstitutional and void:

- The City's legal right to collect the park usage fees from Z (as determined by the Park Ordinance) for the period in question (April 1, 2014, to July 24, 2014) fully existed.

- The LAA (Art. 231-3(1) regarding supervision of revenue collection, Art. 240 regarding management of claims, and related Cabinet Order provisions) generally obligates the head of a local government to collect due revenues and does not grant discretion to waive such claims without valid legal grounds. The Supreme Court cited its 2004 precedent (Minshu Vol. 58, No. 4, p. 892) on this point.

- Although the Naha City Park Ordinance (Art. 11-2, Item 8) allows the Mayor to grant a partial exemption if "specially necessary," no such partial exemption decision had been made by the close of oral arguments in the trial court. There were no other statutory grounds for suspending or ceasing collection.

- Therefore, the Mayor's failure to demand payment of the full Usage Fee in Question from Z constituted an illegal neglect of property management.

The Supreme Court thus upheld X's claim for a declaration of this illegality.

Final Disposition

- Z's (the association's) appeal was dismissed.

- The part of the High Court's judgment that had found against X (the first-instance plaintiff, effectively by implying a partial exemption might be valid) was overturned.

- Regarding this overturned portion, the appeal by Y (the Mayor, first-instance defendant) from the original first-instance judgment (which had found the full omission illegal) was dismissed as a duplicative appeal (since Z's appeal on the same substantive point was already before the SC and being dismissed). Z's appeal from the first-instance judgment was also dismissed.

- Court costs were assigned to Y (the Mayor).

(The judgment also included a dissenting opinion by Justice Hayashi Keiichi, who argued that the facility's religious nature was weak or largely secularized by custom, and that the City's secular aims of tourism and education justified the fee exemption, making it constitutional.)

Implications of the Ruling

The Naha Kume Confucian Temple case is a significant Grand Bench decision that reinforces and clarifies the application of the separation of religion and state principle in Japan:

- "Comprehensive Consideration" Standard Affirmed: The Court continued to apply the "comprehensive consideration of various circumstances in light of social common sense" standard, previously seen in cases like the Sunagawa City shrine land disputes, to determine whether state involvement with religious facilities crosses constitutional boundaries.

- Religious Nature of Confucian Facilities: The judgment explicitly found that a facility like the Kume Shiseibyo, dedicated to Confucius and his disciples and used for ceremonies venerating their spirits, possesses a clear religious character that is not merely "minor" or "attenuated," especially when coupled with practices like selling prayer cards and restricting ceremonial leadership to a specific lineage group.

- High Scrutiny for Gratuitous Use of Public Land: Providing public land free of charge for a newly constructed, primarily religious facility is likely to be deemed unconstitutional, even if some secular public benefits like tourism or historical education are claimed. The Court emphasized the need for a strong justification of necessity and reasonableness if public property is to be used in this manner.

- Limitations on Mayoral Discretion in Waiving Fees: Once usage fees for public property are legally due under an ordinance, a mayor has very limited discretion to waive them entirely, especially if the initial basis for exemption (e.g., for a "public organization" acting for "public interest") is found to be constitutionally flawed due to religious entanglement. The failure to collect such due fees constitutes an illegal neglect of property management.

- Relevance of Historical Context and Actual Use: The Court carefully examined both the historical origins of the Shiseibyo tradition and the actual current use and presentation of the specific facility in Matsuyama Park. While historical continuity was noted, the fact that the current facility was newly built on newly acquired parkland, and that alternative arrangements (like a land swap) had been previously considered by the City itself, weighed against the City's arguments for the necessity of the free provision.

This ruling sends a clear message to local governments about the need for caution and rigorous constitutional scrutiny when dealing with requests for the use of public property by organizations or for facilities that have a discernible religious character or purpose. The "social common sense" standard requires a careful balancing of all relevant factors, with a strong presumption against arrangements that could be perceived by the public as state endorsement or support of a particular religion.