Rooftop Additions in Japan: Who Owns Them? A Supreme Court Look at Accession

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of July 25, 1969 (Showa 44) (Case No. 120 (O) of 1969 (Showa 44))

Subject Matter: Claim for Building Removal and Land Vacation (建物収去土地明渡請求事件 - Tatemono Shūkyo Tochi Akewatashi Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

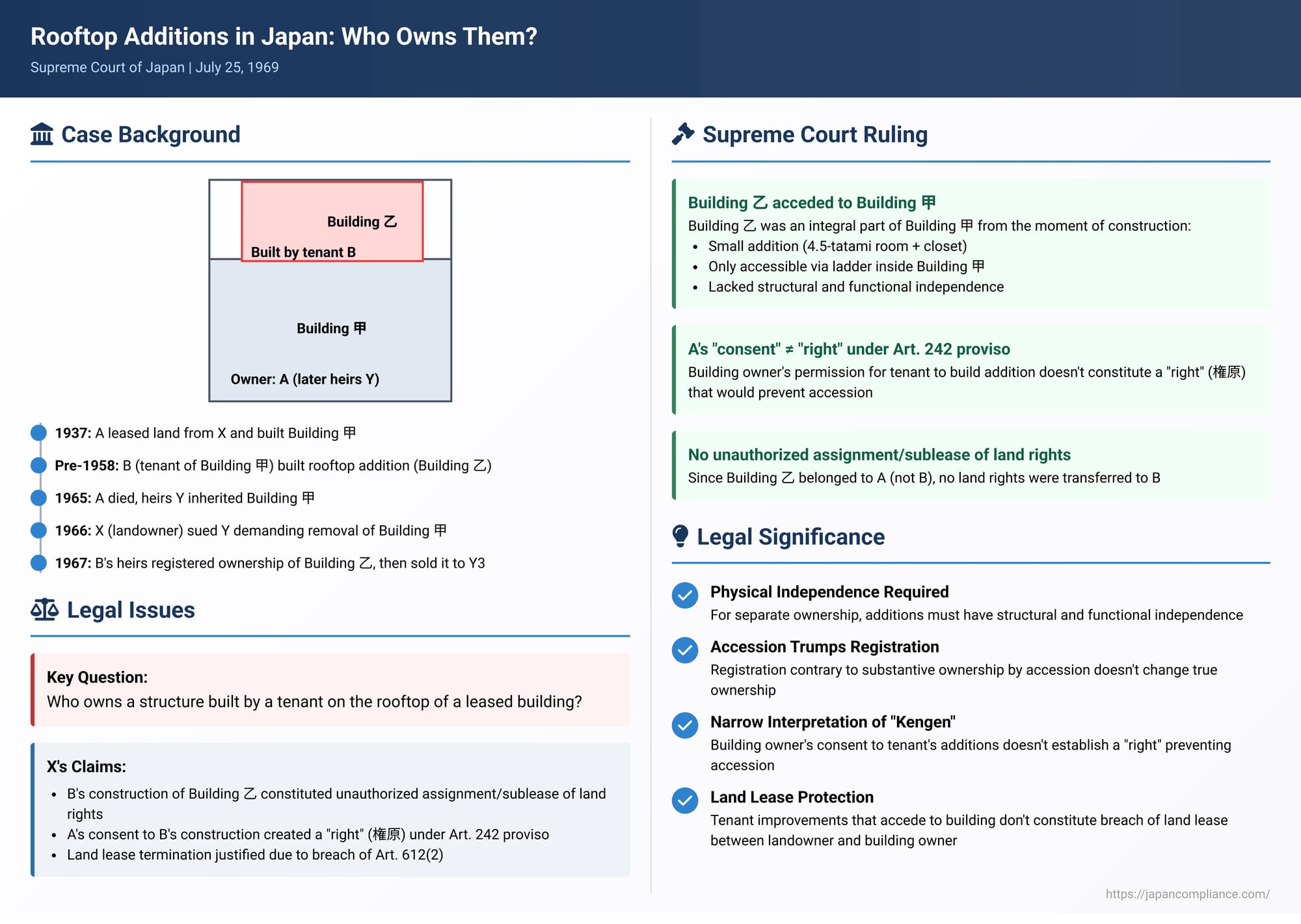

This article delves into a 1969 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses the ownership of structures built by a tenant on the rooftop of a leased building. The central legal question was whether such a rooftop addition becomes the separate property of the tenant who constructed it, or if it accedes to the main building, thereby becoming the property of the building's owner. The Court's decision hinges on the physical characteristics of the addition, its degree of independence from the main structure, and the interpretation of "right" (権原 - kengen) under Article 242 of the Civil Code concerning accession to immovables. The case also touched upon whether such an addition by a building tenant could be construed as an unauthorized assignment or sublease of the underlying land rights by the building owner (who was also the land lessee).

The dispute involved X (appellant/plaintiff), the landowner, and Group Y (appellees/defendants), who were the heirs of A, the original lessee of the land and owner of the main building (Building 甲). The controversy also involved B, a tenant of part of Building 甲, who constructed the rooftop structure (Building 乙).

Factual Background

Around 1937, A leased a parcel of land (the "Land") from X for the purpose of owning a building. A constructed a one-story wooden residential building (Building 甲) on this Land. B subsequently leased a part of Building 甲 from A. Sometime before 1958, B, at his own expense, constructed an additional structure (Building 乙) on the rooftop of Building 甲. X alleged that A had consented to B's construction of this rooftop addition.

Building 乙 consisted of a 4.5-tatami mat room and a closet. The only way to access Building 乙 from the outside was via a ladder located within a six-tatami mat room inside Building 甲.

In March 1965, A passed away, and his leasehold rights to the Land and ownership of Building 甲 were inherited by his heirs, Group Y (Y1-Y6).

In October 1966, X (the landowner) sued Group Y, demanding the removal of Building 甲 and the vacation of the Land. X's claim was based on the argument that A had, without X's consent, effectively assigned the leasehold rights for the portion of the Land under Building 乙 to B, or had sublet that portion of the Land to B, by allowing B to construct and own Building 乙. X asserted this constituted a breach under Article 612, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, entitling X to terminate the land lease agreement with A (and consequently with his heirs, Group Y).

Separately, in July 1967, B's heirs (C et al.) completed an ownership preservation registration for Building 乙. On the same day, ownership of Building 乙 was registered as transferred from C et al. to Y3 (one of A's heirs and a member of Group Y) due to a sale. The building registry description for Building 乙 incorrectly described it as a one-story structure, contrary to its actual rooftop nature. X also sued Y3, demanding the removal of Building 乙 and vacation of the Land based on X's land ownership.

The appellate court had overturned a first-instance judgment that had favored X (due to Group Y's insufficient litigation activity at that stage). The appellate court dismissed X's claims, reasoning similarly to the Supreme Court's eventual judgment. X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that Building 乙 was an independent building owned by B (and then his successors), that Article 242's proviso regarding accession should apply due to A's consent, and that, in any case, the land lease was validly terminated due to the unauthorized assignment/subletting of land use rights to B.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the appellate court's decision.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of the Rooftop Structure (Building 乙):

The Court found that Building 乙, constructed by B (tenant of part of Building 甲) on the rooftop of Building 甲, consisted of a 4.5-mat room and a closet, with the only access being a ladder inside a room in Building 甲.

Given these physical characteristics, Building 乙 was essentially a second-floor addition built on top of the existing Building 甲, forming an integral part of its structure. It lacked transactional independence and did not qualify as a part of a building capable of separate ownership under the rules of sectional ownership (建物の区分所有権 - tatemono no kubun shoyūken). - Accession under Civil Code Article 242:

Article 242 of the Civil Code states that the owner of an immovable acquires ownership of things affixed thereto as its components. The proviso to Article 242 allows a person who has affixed their thing to another's immovable by virtue of a right (権原 - kengen) to retain ownership if their thing does not become an integral part (i.e., it remains distinct and separable).

The Supreme Court held that even if A (owner of Building 甲) had consented to B's construction of Building 乙, such consent does not constitute a "right" (kengen) within the meaning of the proviso to Article 242 that would allow B to retain separate ownership of Building 乙.

The Court reasoned that Building 乙, due to its structure and lack of independence, became an integral part of Building 甲. Therefore, by operation of accession, ownership of Building 乙 vested in A (the owner of Building 甲) from the moment of its construction. - Effect of Registration of Building 乙:

The fact that B's heirs (C et al.) later completed an ownership preservation registration for Building 乙 in their names did not alter the substantive ownership determined by the principle of accession. Registration reflects, but does not create, ownership in such accession scenarios unless other principles (like bona fide acquisition, not relevant here) apply. - No Unauthorized Assignment or Sublease of Land Rights:

Since Building 乙 acceded to Building 甲 and became A's property, B's construction of Building 乙 did not mean that A had assigned or sublet the leasehold rights for the underlying land portion to B. B was merely making an addition to A's building, which then became A's property. There was no transfer of land use rights from A to B that would trigger X's right to terminate the land lease under Article 612, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code.

Therefore, the appellate court's judgment, which found no grounds for terminating the land lease and thus dismissed X's claims, was correct.

The appeal was dismissed.

Analysis and Implications

This 1969 Supreme Court judgment provides important clarifications on the law of accession concerning building additions and its impact on lease relationships.

- Structural and Functional Independence for Separate Ownership: For an addition to a building to be considered a separate object of ownership (and not accede to the main building), it must have both structural and functional independence. In this case, Building 乙's complete dependence on Building 甲 for access and its nature as a rooftop structure integrated into the main building led to the conclusion that it lacked such independence. This aligns with the general requirements for sectional ownership.

- Lessor's Consent to Alterations vs. "Kengen" under Article 242 Proviso: A crucial point is the Court's interpretation of "kengen" (right) in the proviso to Article 242. The Court held that a building owner's (A's) consent to a tenant's (B's) making an addition does not, by itself, constitute a "kengen" that allows the tenant to retain separate ownership of the addition if it physically accedes to and becomes an integral part of the main building.

- Such consent typically means that the tenant is not breaching their lease terms by making alterations (e.g., not violating rules against unauthorized modifications). It does not automatically grant the tenant a separate real right over the addition that would prevent accession.

- For the proviso to apply and prevent accession of an attached component, the person affixing the item usually needs a more substantial right that justifies their separate ownership of the affixed item despite its attachment (e.g., a landowner allowing someone to build a separable structure on their land with an agreement it remains the builder's property).

- Accession as the Primary Determinant of Ownership: When a structure lacks independence and is affixed to a principal building, the rule of accession (Article 242 main text) generally governs ownership, vesting it in the owner of the principal building. Subsequent registrations that contradict this substantive ownership (like the preservation registration by B's heirs for Building 乙) do not change the underlying ownership determined by accession.

- Implications for Landlord-Tenant Law: The ruling clarifies that additions made by a building tenant that accede to the main building do not automatically imply a transfer or sublease of the underlying land rights from the building owner (who is the land lessee) to the building tenant. This is because the addition becomes part of the building owner's property. Therefore, the landowner cannot typically terminate the land lease based on an unauthorized assignment or sublease solely because a building tenant made such an acceding addition with the building owner's consent.

- Protecting Landowner's Ultimate Rights: While the landowner (X) could not terminate the land lease on these grounds, their ultimate rights are protected by the fact that upon termination of the land lease for other valid reasons (e.g., end of term, non-payment of land rent by Group Y), they could demand the removal of the entire structure (Building 甲 including the acceded Building 乙) or exercise other remedies available to a landowner against a former lessee.

This judgment underscores that the physical nature of an addition to a building and its degree of independence are paramount in determining whether it accedes to the main structure or can be separately owned. Simple consent by the building owner to an alteration by a tenant does not typically override the rules of accession if the addition becomes an integral part of the building. This has important consequences for ownership disputes and for assessing whether such alterations trigger grounds for terminating underlying land leases.