Road Blocked, Rights Asserted: How Japanese Villagers Won the Right to Sue Over Obstructed Public Ways

Judgment Date: January 16, 1964

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

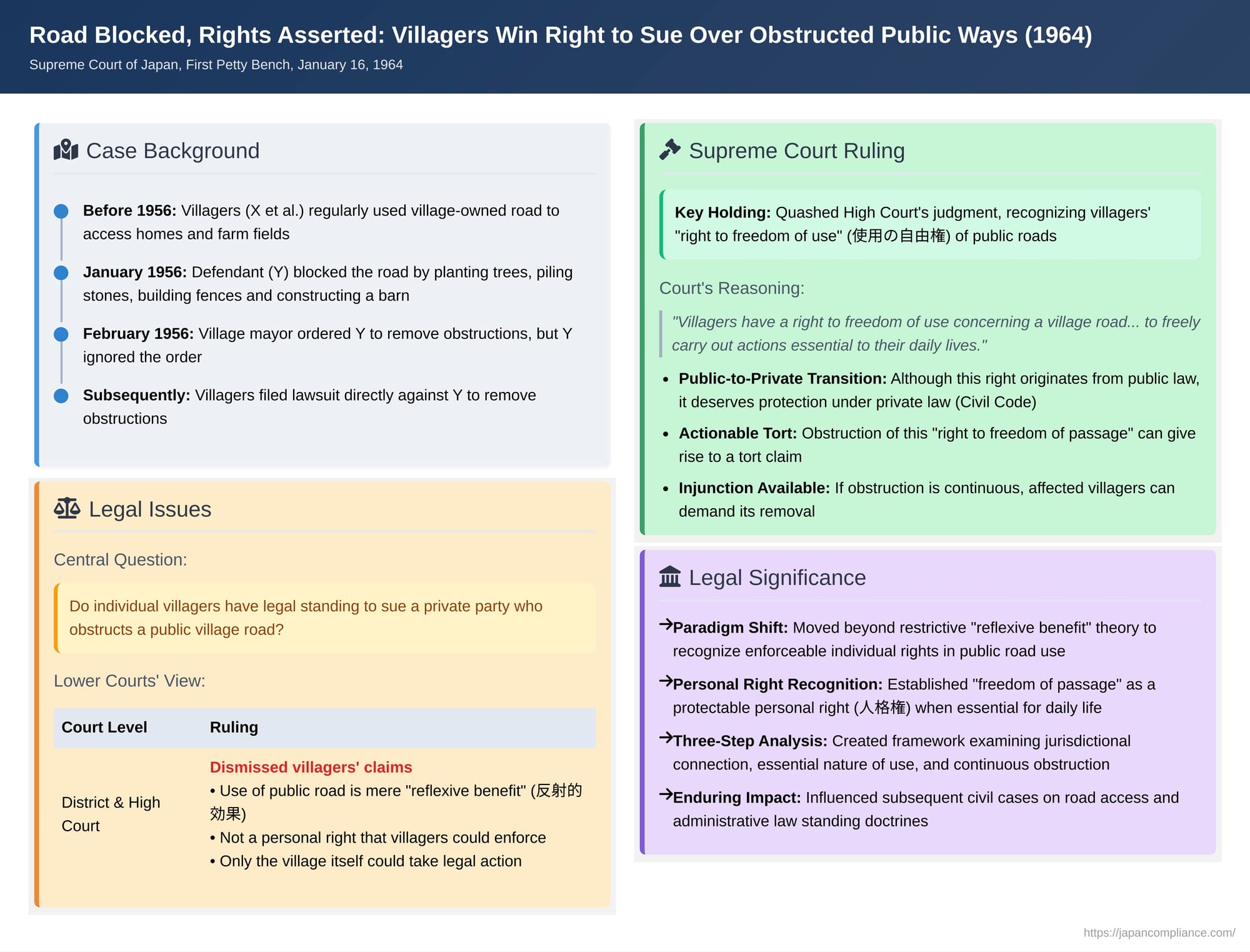

Can ordinary citizens take direct legal action against a private individual who blocks their access to a public road? This fundamental question of public access and private rights was at the heart of a landmark 1964 Japanese Supreme Court decision. The case involved villagers whose daily use of a village-owned road was obstructed, and it set a crucial precedent by recognizing a protectable "right to freedom of use" for essential daily activities, even if that right originates from public law.

The Blocked Village Road: A Community's Access Denied

The dispute centered on a village road in Ano Village, Mie Prefecture. The road itself, including the land it was on, was owned by the village[cite: 1]. For decades, the plaintiffs, X et al., who were local residents, had relied on this road for everyday activities – accessing their homes and traveling to their agricultural fields[cite: 1].

This longstanding access was abruptly cut off around January 1956[cite: 1]. Y, another individual, began to treat the village road as his own. He planted trees, piled up stones, erected a wooden fence, and even constructed a one-story wooden barn with a concrete foundation directly on the road[cite: 1]. These actions effectively created an exclusive occupation by Y, making the road impassable for X et al. and other villagers[cite: 1].

It's noteworthy that the village authorities were not entirely passive. In February 1956, while Y's barn was still under construction, the village mayor issued an official order instructing Y to remove the obstructions and cease his interference with the road[cite: 1]. However, Y disregarded this order and completed the barn[cite: 1].

Frustrated and with their daily lives disrupted, X et al. took Y to court[cite: 1]. They based their claim for the removal of the obstructions on several grounds: primarily, their general right of passage as villagers, and a public law right to use agricultural roads based on local custom[cite: 1]. In the appeal stage, they also added a claim of having acquired a right of way by prescription[cite: 1].

Lower Courts: A "Reflexive Benefit," Not a Right to Sue

The initial legal battles did not go in favor of the villagers. Both the Tsu District Court (First Instance) and the Nagoya High Court (Second Instance) dismissed their claims[cite: 1].

The core reasoning of these lower courts was that the villagers' ability to use the road was not an inherent, individual right[cite: 1]. Instead, it was merely a "reflexive benefit" (hanshateki kōka) – an incidental advantage they enjoyed because the village had officially opened and maintained the road for public use[cite: 1]. According to this view, while the village itself, as the road's owner and administrator, could certainly take action against Y to remove the obstructions, individual villagers, in their personal capacity, did not possess a direct legal right to sue Y for such removal[cite: 1]. The High Court also dismissed the argument that long-term use automatically created a prescriptive right of way[cite: 1].

X et al. appealed to the Supreme Court[cite: 1]. They argued that even if their freedom to use the village road was considered merely "reflexive," the lower courts had failed to provide adequate legal justification for why they, as affected individuals, could not seek the removal of obstructions directly from Y, the private party causing the infringement[cite: 1]. They contended this was a misinterpretation of tort law principles under Civil Code Article 709[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's Turnaround: Recognizing a "Right to Freedom of Use"

In a significant departure from the lower courts' stance, the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings[cite: 1]. The Supreme Court's reasoning laid a new foundation for understanding citizens' rights concerning public roads:

- A Protectable Right: The Court held that individual villagers have a "right to freedom of use" (shiyō no jiyūken) concerning a village road established by their local public entity[cite: 1]. This right allows them to freely carry out actions essential to their daily lives, provided they do not infringe upon the similar interests or freedoms of other villagers using the same road[cite: 1]. The Court notably referenced Article 710 of the Civil Code in this context[cite: 1].

- From Public Law Origin to Private Law Protection: The Supreme Court acknowledged that this "right to freedom of passage" (tsūkō no jiyūken, as it also termed it) originates from a public law relationship (i.e., the road being a public facility)[cite: 1]. However, because this right is an "indispensable tool for individuals to exercise various rights in their daily lives," it naturally deserves protection under private law (specifically, the Civil Code)[cite: 1].

- Basis for Legal Action: Consequently, if a villager's right to freedom of use is obstructed by another party, this obstruction can give rise to a tort claim under private law[cite: 1]. Furthermore, if such an obstruction is continuous, the affected villager "has the right to demand its removal"[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court found that the lower courts had not adequately examined the factual circumstances to determine whether X et al.'s use of the road indeed fell within this protected category and whether Y's actions constituted a continuous obstruction of such essential use[cite: 1].

Unpacking the Legal Shift: From "Reflexive Benefit" to Individual Right

This 1964 judgment marked a pivotal shift in Japanese jurisprudence regarding the use of public property.

Beyond "Reflexive Benefit":

Traditionally, Japanese legal theory, particularly concerning public property like roads, rivers, and coastlines ("public things" or kōbutsu), distinguished between the public entity managing the property and the general public using it. While such public things were understood to be available for "free use" or "general use" by the public, the benefit individuals derived from this use was often characterized as a mere "reflexive benefit"[cite: 1]. This meant it wasn't considered a distinct legal "right" belonging to the individual user but rather an indirect consequence of the public entity making the facility available[cite: 1]. Before this Supreme Court decision, it was not clearly established whether an individual had any legal recourse if a private party interfered with this free use[cite: 2]. The prevailing view was that a legal claim to demand the removal of an obstruction (an injunction) typically had to be based on a recognized property right (bukken) or a similar right with effect against the world (erga omnes), not merely on the infringement of a reflexive benefit of residents[cite: 1].

This Supreme Court ruling effectively moved beyond the restrictive "reflexive benefit" theory in the context of essential road use by local residents.

The "Right to Freedom of Passage" as a Personal Right:

The Supreme Court carefully framed the recognized interest not as an unlimited general right but as a "right to freedom of use...for actions essential to one's daily life"[cite: 1]. The Court specifically referred to this as the "right to freedom of passage" (tsūkō no jiyūken)[cite: 1]. The reference to Civil Code Article 710 is particularly telling[cite: 1]. Article 710 deals with compensation for non-pecuniary damages (e.g., emotional distress) in tort cases and explicitly lists "body, liberty, honor" as examples of interests whose infringement can lead to such damages[cite: 3]. By citing this article, the Supreme Court signaled that it viewed this "freedom of passage," when essential for daily life, as a type of personal right (jinkakuken), deserving of robust legal protection[cite: 3].

The Court's reasoning suggests a three-step analysis for such cases[cite: 3]:

- Jurisdictional Connection: Does the case involve a public road (like a village road) and are the plaintiffs residents (like villagers) with a direct connection to its use? (The commentary suggests this could extend to those in a similar position, e.g., villa residents using a public access road)[cite: 3].

- Essential Nature of Use: Is the plaintiffs' use of the road for "actions essential to their daily life"? If yes, this use crystallizes into a "right to freedom of passage," which is considered a personal right warranting private law protection. Obstruction of this right constitutes a tort[cite: 3].

- Continuous Obstruction for Injunctive Relief: If the obstruction is ongoing or continuous, the affected individuals have the right to demand its removal through an injunction[cite: 3].

The case was remanded for the High Court to specifically examine the facts related to points (2) and (3)[cite: 3].

Choosing the Right Lawsuit: Why a Civil Action?

The plaintiffs' decision to file a civil lawsuit directly against Y, the obstructor, rather than an administrative lawsuit targeting the village or its mayor, was deemed reasonable by legal commentators[cite: 1]. Several factors likely influenced this choice: the village mayor had already issued an administrative order against Y, which Y had ignored[cite: 1]; the legal requirements for direct administrative enforcement (like gyōsei daishikkō, or administrative execution on behalf of the delinquent party) were stringent[cite: 1]; and at that time, certain types of administrative lawsuits now available (like a mandatory injunction compelling administrative action) were not yet established in law[cite: 1]. Furthermore, options like resident audit requests or taxpayer lawsuits under the Local Autonomy Act were more limited in scope before later amendments[cite: 1].

Legacy of the Ruling: Impact on Subsequent Cases and Administrative Law

The 1964 Supreme Court decision has had a lasting impact:

- Subsequent Civil Cases: Many subsequent court decisions have relied on this concept of a "right to freedom of passage" to grant private law protection against obstructions, further developing the criteria for what constitutes "essential use" and "continuous obstruction"[cite: 4]. The principle has even been extended to certain types of privately-owned roads that serve a public access function, such as "position-designated roads" (ichi shitei dōro) under the Building Standards Act, with courts affirming the right to seek injunctions against their obstruction, and in some cases, even injunctions against future obstruction[cite: 4].

- Ripple Effects in Public Law: The ruling also prompted discussions about its potential impact on administrative law, particularly whether this "right to freedom of passage" could ground a plaintiff's standing (i.e., establish a "legal interest" under Article 9, Paragraph 1 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act) to challenge administrative actions like the closure or abolition of a public road[cite: 4].

While post-1964 administrative case law often continued to invoke the "reflexive benefit" theory to deny standing to general users, many courts began to recognize an exception: standing could be affirmed if the road provided an "individual and specific benefit" to the plaintiff and its closure would cause "significant hindrance to the plaintiff's life" – essentially, where "special circumstances" existed[cite: 4]. A 1987 Supreme Court case concerning a "village path" (ridō) acknowledged this possibility, though it found such circumstances lacking for the specific appellant in that instance[cite: 4].

The 2004 amendments to the Administrative Case Litigation Act (specifically Article 9, Paragraph 2) now explicitly direct courts to consider the nature and extent of the interest to be affected, including such "special circumstances"[cite: 4]. The direction indicated by the 1964 ruling, focusing on the essential nature of the use for daily life, aligns with this more nuanced approach to standing in administrative cases, although the precise harmonisation between the civil law "right to freedom of passage" and the administrative law criteria for "legal interest" remains a subject of ongoing legal discussion[cite: 4].

Conclusion: Affirming Individual Rights in the Use of Public Amenities

The 1964 Supreme Court judgment represents a crucial step in Japanese law toward recognizing and protecting the tangible interests of individuals in the use of public roads essential for their daily existence. By moving beyond the restrictive notion of "reflexive benefit" and articulating a "right to freedom of use" grounded in private law, the Court empowered citizens to directly confront private obstructions that impair their fundamental ability to live and work. This decision not only provided a remedy for the affected villagers in Ano Village but also laid down a principled foundation that has influenced the protection of public access rights in Japan for decades since.