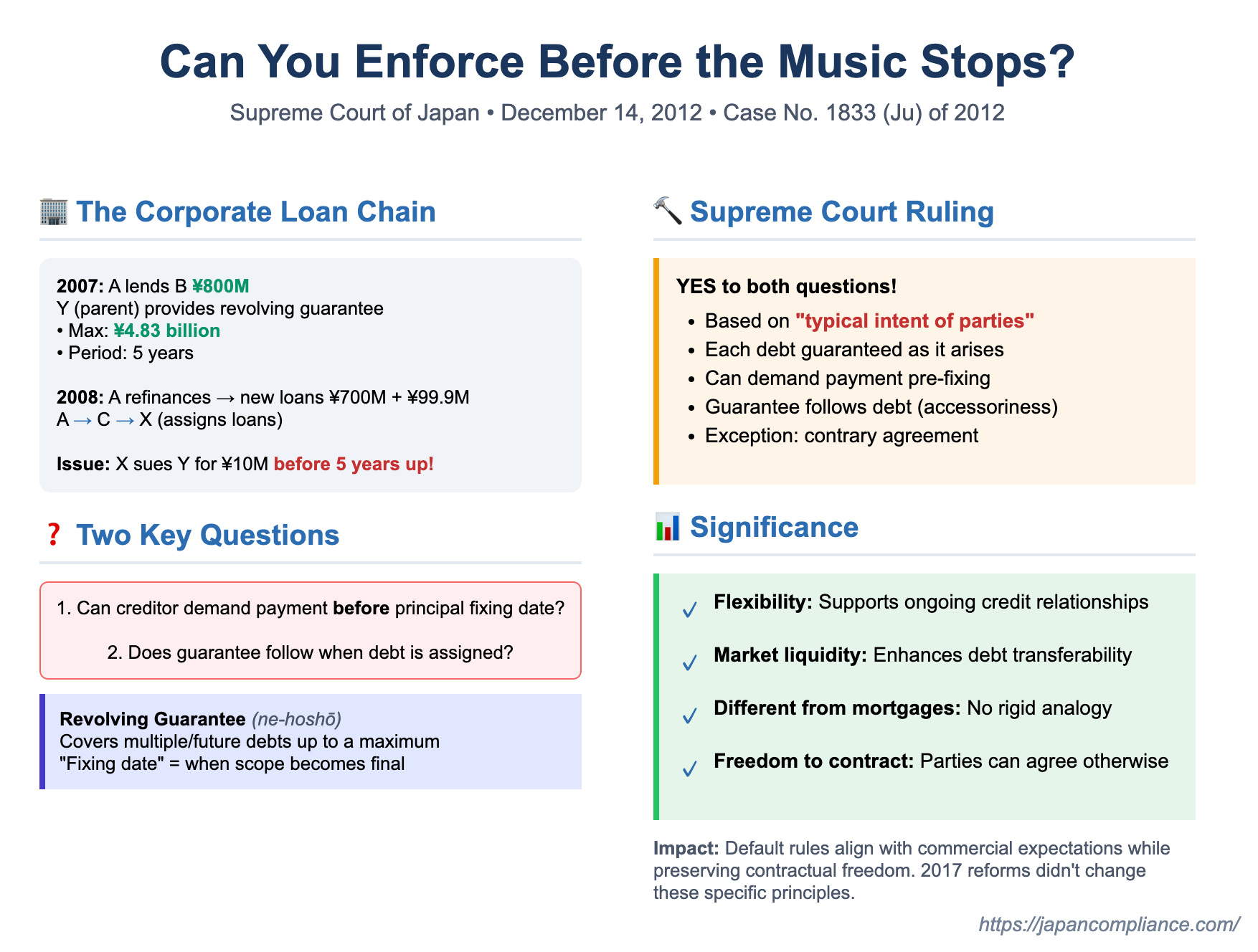

Revolving Guarantees in Japan: Can Creditors Demand Payment Before the "Fixing Date"? Does the Guarantee Follow an Assigned Debt?

Revolving guarantees (ne-hoshō) are a common tool in Japanese commercial transactions, providing security for a series of ongoing or future debts up to a pre-agreed maximum amount. Unlike a guarantee for a single, specific loan, a revolving guarantee covers a fluctuating range of obligations. But this flexibility raises critical questions: Can a creditor demand payment from the guarantor for an individual debt that becomes due before the overall scope of the guarantee is finalized (i.e., before its "principal fixing date")? And if the creditor sells (assigns) one of these individual debts to another party before this fixing date, does the protection of the revolving guarantee automatically transfer to the new debt holder? The Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial answers in its judgment on December 14, 2012 (Heisei 23 (Ju) No. 1833). [cite: 1]

Understanding Revolving Guarantees (Ne-Hoshō)

A revolving guarantee in Japan is defined as a guarantee for "unspecified debts within a certain scope" that arise from a continuous relationship between a creditor and a principal debtor (Article 465-2, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code). [cite: 1] Key features often include:

- A maximum limit amount (kyokudogaku) for the guarantee.

- A guarantee period or events that trigger a "principal fixing date" (ganpon kakutei kijitsu). Once this date occurs, the specific debts covered by the guarantee become fixed, and no new debts arising thereafter are covered.

This case specifically addressed what happens before this principal fixing date.

The Facts of the Case: A Corporate Guarantee, Refinancing, and Assignment

The dispute involved several corporate entities:

- The Initial Loan and Guarantee: On June 29, 2007, Company A lent 800 million yen to Company B (Loan ①), with a due date of June 5, 2008. On the same day, Company Y (Company B's parent company) provided a joint and several revolving guarantee to Company A for Company B's debts arising from loan agreements and other transactions. This guarantee had a maximum limit of 4.83 billion yen and a specified guarantee period of five years from June 29, 2007. [cite: 1]

- Refinancing: On August 25, 2008 (after Loan ① would have matured but within the guarantee period), Company A effectively refinanced Loan ① by providing two new loans to Company B: 700 million yen (Loan ②) and 99.9 million yen (Loan ③), both due August 5, 2009. [cite: 1]

- Assignment of the New Loans: On September 26, 2008—still well within the five-year guarantee period and thus before the principal fixing date—Company A assigned its rights to Loan ② and Loan ③ to Company C. On that same day, Company C assigned these same loan claims to Company X (the plaintiff). [cite: 1]

- The Lawsuit: Company X then sued Company Y (the guarantor) for 10 million yen (as a portion of the nearly 800 million yen total from Loans ② and ③), seeking performance under the revolving guarantee contract. [cite: 1]

Company Y argued, among other things, that similar to a revolving mortgage (ne-teitōken), a revolving guarantee should not be enforceable for individual debts by an assignee before the principal is fixed. The lower courts disagreed, finding no statutory basis to deny such claims for revolving guarantees and noting that the legal complexities were different from revolving mortgages. [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Affirming Pre-Fixing Liability and Accessoriness

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of Company X. [cite: 1] The Court's reasoning was primarily based on a "rational interpretation of the typical intent of parties" entering into a revolving guarantee contract:

- Individual Debts Guaranteed as They Arise: The Court stated that parties to a revolving guarantee typically understand that the guarantor will guarantee each individual debt as it comes into existence, provided it falls within the agreed scope of the primary obligations covered by the revolving guarantee. [cite: 1]

- Performance Can Be Demanded Before the Principal Fixing Date: When such an individual guaranteed debt matures, it is normally intended that the creditor can demand performance of the guarantee obligation from the guarantor, even if the overall "principal fixing date" for the revolving guarantee (in this case, the day after the five-year guarantee period expired) has not yet arrived. [cite: 1]

- Guarantee Follows the Debt (Accessoriness): The Court found it rational to assume that these parties also presume that if a specific debt covered by the revolving guarantee is assigned to a new creditor, the benefit of the guarantee for that debt will transfer along with it to the assignee. This is the principle of "accessoriness" or "attendant nature" (zuihansei). [cite: 1]

- Assignee Can Sue (Unless Specifically Agreed Otherwise): Consequently, an assignee who acquires a debt covered by a revolving guarantee can demand performance from the guarantor, even if the assignment and the demand occur before the principal fixing date. The only exception would be if there was a contrary agreement between the original parties to the revolving guarantee (i.e., the original creditor, the principal debtor, and the guarantor) that would prevent or limit the assignee's claim. [cite: 1]

In this particular case, the Supreme Court found no evidence of such a "contrary agreement" that would bar Company X's claim. [cite: 1]

Justice Sudoh's Concurring Insights

Justice Sudoh Masahiko provided a supplementary opinion, concurring with the Court's conclusion but adding further emphasis:

- Freedom of Contract: He stressed that parties are free to structure their revolving guarantee agreements differently. For instance, they could explicitly agree that the guarantee will not transfer with assigned debts or that it only covers debts owed by the principal debtor to the original creditor at the time the principal is fixed. [cite: 1]

- Interpretation of This Specific Contract: Justice Sudoh pointed to the wording of the actual guarantee document in this case. It explicitly stated that the guarantor (Company Y) guaranteed existing debts, debts arising during the five-year guarantee period, and even debts among these that the original creditor (Company A) assigned to Company C. This language, he noted, clearly did not support an interpretation that the guarantee was limited to debts owed only to Company A at the fixing date. [cite: 1]

- Economic Reality: He also observed that Loans ② and ③ were essentially refinancings of Loan ①, which was an originally guaranteed debt. Since a guarantee for Loan ① would normally transfer if Loan ① were assigned, it was within Company Y's reasonable expectation that the guarantee for its economic equivalents (Loans ② and ③) would also be transferable and enforceable by an assignee. [cite: 1]

Why This Ruling Matters: Clarity for Lenders, Guarantors, and the Market

This 2012 Supreme Court judgment provided significant clarity in an area of law where explicit statutory guidance was previously lacking for these specific points.

- Departure from Strict Revolving Mortgage Analogy: Revolving mortgages in Japan have specific statutory provisions that deny accessoriness and demands against the collateral for individual debts before the principal is fixed (Civil Code Arts. 398-7 and 398-3). [cite: 1] The Supreme Court consciously chose not to rigidly apply this framework to revolving guarantees, recognizing the different legal nature and practical considerations involved (e.g., revolving guarantees don't involve the same concerns for junior lienholders or issues with partial foreclosure that affect revolving mortgages). [cite: 1]

- Default Rules Based on Presumed Commercial Intent: The decision establishes important default rules for interpreting revolving guarantee agreements. It presumes that parties generally intend for these guarantees to be flexible and supportive of ongoing credit relationships, which includes allowing enforcement for matured individual debts pre-fixing and allowing the guarantee to follow assigned debts. This provides a baseline for commercial understanding but importantly allows parties the freedom to contract for different terms if they so choose. [cite: 1]

- Enhanced Assignability of Guaranteed Debt: By affirming pre-fixing accessoriness as the default, the ruling enhances the commercial value and transferability of debts that are backed by revolving guarantees, facilitating liquidity in the credit market.

- Scholarly Discussion: The judgment was generally welcomed by financial practitioners for aligning with common commercial expectations. [cite: 1] However, some legal scholars have questioned the assumption of a universal "typical intent" applicable to all revolving guarantees, suggesting that the specific facts of this case (corporate parties, the refinancing nature of the debt, the explicit wording noted by Justice Sudoh) might have allowed for a narrower, case-specific interpretation affirming accessoriness without laying down such a broad default rule. [cite: 1] There were also concerns raised about broadly applying this default to personal guarantors, for whom pre-fixing liability to assignees could potentially be harsh. [cite: 1]

The Situation After the 2017 Civil Code Reforms

This 2012 judgment was issued at a time when the statutory framework for revolving guarantees was still evolving. The extensive 2017 reforms to the Japanese Civil Code addressed many aspects of personal revolving guarantees, most notably by requiring all personal revolving guarantees to have a specified maximum amount. [cite: 1] However, the reforms did not explicitly codify the answers to the questions of pre-fixing performance demands and pre-fixing accessoriness for all types of revolving guarantees, meaning this 2012 Supreme Court decision remains significant interpretative guidance on these points. [cite: 1]

Conclusion

The 2012 Supreme Court decision provides crucial clarity on the operation of revolving guarantees in Japan. It confirms that, based on a rational interpretation of the presumed intent of the contracting parties, guarantors can generally be held liable for individual guaranteed debts that mature even before the guarantee's overall principal is fixed. Furthermore, the protection of the revolving guarantee will typically follow such a debt if it is assigned to a new creditor, unless the parties to the original guarantee have explicitly agreed otherwise. This ruling supports the practical dynamics of commercial lending and debt assignment while respecting the fundamental principle of freedom of contract.