Revoking a Revocation: The Henoko Permit Case and Judicial Review of Ex Officio Powers

Date of Judgment: December 20, 2016, Second Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

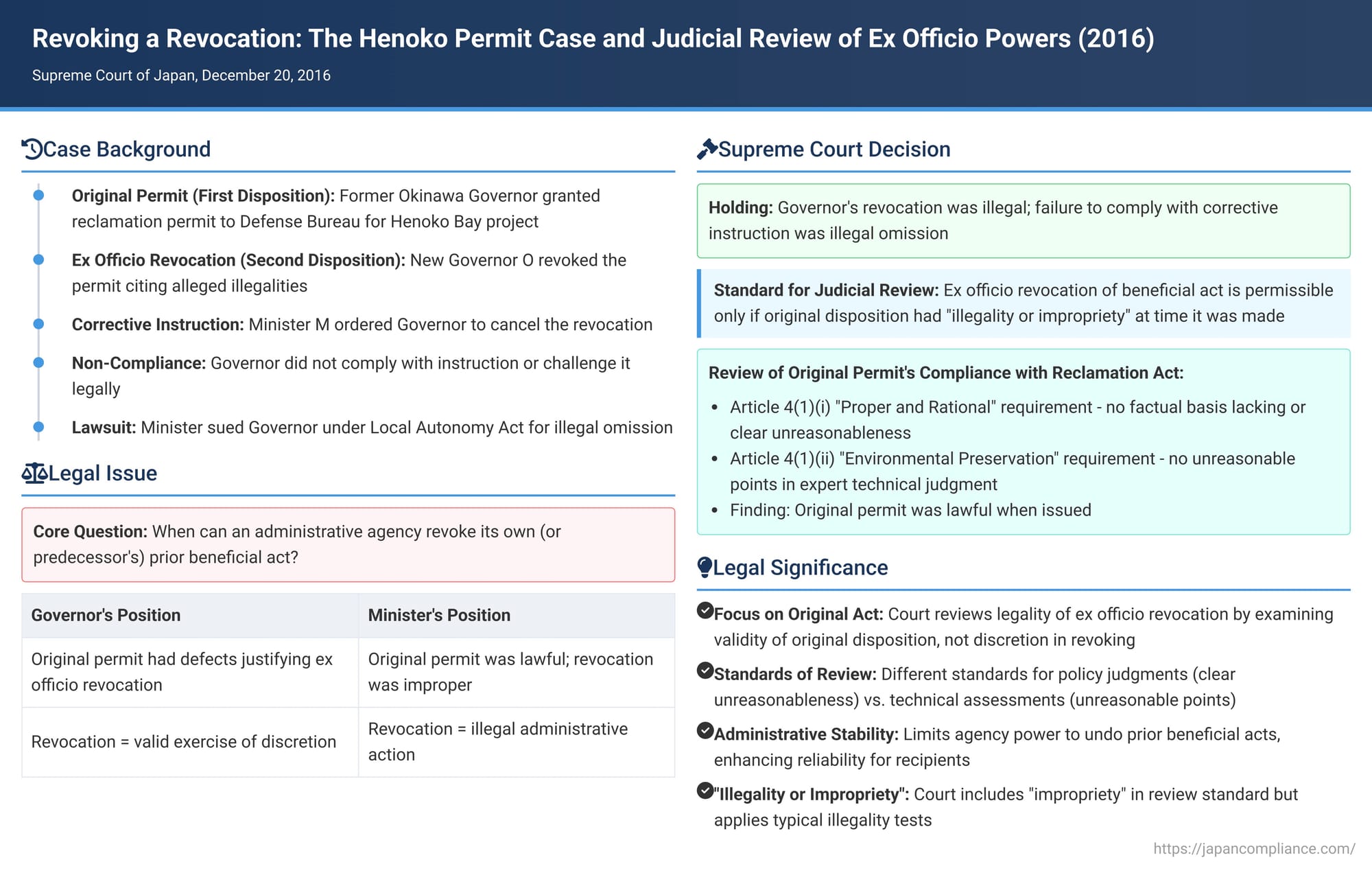

Administrative law grapples with the power of government agencies to reconsider and undo their prior decisions. This power, known as ex officio revocation (職権取消 - shokken torikeshi), is particularly complex when it involves withdrawing a beneficial administrative act, such as a permit, based on alleged flaws in the original decision. A highly publicized Japanese Supreme Court ruling on December 20, 2016, concerning the controversial U.S. military base relocation project in Henoko, Okinawa Prefecture, provided significant clarification on the judicial standards for reviewing such ex officio revocations. The case underscored that the legality of an agency's decision to revoke its (or its predecessor's) prior beneficial act hinges critically on whether that original act was indeed unlawful or improper.

The Factual Background: The Henoko Reclamation and a Disputed Revocation

The case arose from the long-standing plan to relocate the U.S. Marine Corps Futenma Air Station to a new facility to be constructed on reclaimed land in Henoko Bay, Nago City, Okinawa Prefecture.

- The Original Reclamation Permit (First Disposition): The former Governor of Okinawa Prefecture had granted a permit (the Original Permit) to the Okinawa Defense Bureau (a national government entity) under the Public Water Surface Reclamation Act (hereinafter, the Reclamation Act). This permit authorized the reclamation of public waters in Henoko Bay necessary for the construction of the new airfield (the Reclamation Project).

- The Ex Officio Revocation (Second Disposition): Subsequently, a new Governor of Okinawa Prefecture, Governor O (Y in this summary, the defendant/appellant), took office. Governor O, citing alleged illegalities in the Original Permit granted by his predecessor, decided to ex officio revoke that permit (this revocation is the Second Disposition).

- The Corrective Instruction: The Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Minister M (X in this summary, the plaintiff/appellee), determined that Governor O's ex officio revocation (the Second Disposition) was itself illegal. Minister M then issued a "corrective instruction" (是正の指示 - zesei no shiji) to Governor O under Article 245-7, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act. This instruction directed Governor O to cancel his own revocation, effectively reinstating the Original Permit.

- Non-Compliance and Lawsuit: Governor O did not comply with Minister M's corrective instruction within the specified timeframe and also did not file a lawsuit to challenge the instruction itself (as provided for under Article 251-5, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act). Consequently, Minister M initiated this lawsuit under Article 251-7, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act, seeking a judicial confirmation that Governor O's failure to comply with the corrective instruction (i.e., his failure to undo the revocation) was illegal.

- Lower Court Ruling: The Fukuoka High Court, Naha Branch (which has original jurisdiction over such inter-governmental disputes under the Local Autonomy Act) ruled in favor of Minister M. It found that Governor O's ex officio revocation of the Original Permit was illegal, and therefore his failure to comply with the Minister's corrective instruction was also illegal. Governor O appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Core: Reviewing an Agency's Power to Undo Its Own (or a Predecessor's) Beneficial Act

The central legal issue was the validity of Governor O's ex officio revocation of the Original Permit. If this revocation was lawful, then Governor O was not obliged to follow Minister M's corrective instruction. Conversely, if the revocation was unlawful, then Governor O's failure to comply with the instruction would be illegal. The power of an administrative agency to revoke its prior beneficial decisions ex officio is a significant one, implicating legal stability and the protection of legitimate expectations. The key question is how courts should review such an exercise of power.

The Supreme Court's Decision of December 20, 2016

The Supreme Court dismissed Governor O's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's ruling in favor of Minister M. The Court found that Governor O's ex officio revocation of the Original Permit was indeed illegal.

1. The Object and Standard of Judicial Review for Ex Officio Revocation

The Court first laid down the general principle for reviewing an ex officio revocation of a beneficial administrative disposition when that revocation is based on alleged defects in the original disposition:

- "Generally, when an administrative agency ex officio revokes a disposition that is beneficial to the addressee, on the grounds that there was a defect in said disposition at the time it was made, and the question of whether there was a defect sufficient to warrant such ex officio revocation is contested, the court's examination and judgment on this point should be conducted from the perspective of whether, in light of the circumstances at the time the said disposition was made, it is recognized that there was illegality or impropriety (hereinafter 'illegality, etc.') in said disposition.

- "If such illegality, etc., is not recognized, it must be said that it is not permissible for the administrative agency to ex officio revoke said disposition on the grounds that there was illegality, etc., in it, and such revocation is illegal.

- Applying this to the current case, the Court stated that the appropriateness of Governor O's ex officio revocation (the Second Disposition) should not be judged by whether Governor O abused his discretion in the act of revoking. Instead, the Court must examine whether the Original Permit (the First Disposition) granted by the former Governor was itself "illegal, etc." at the time it was made. If the Original Permit was not illegal, etc., then Governor O's revocation of it is illegal.

2. Review of the Original Reclamation Permit (First Disposition)

The Supreme Court then proceeded to examine the legality and propriety of the Original Permit, focusing on its compliance with the key requirements of Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Reclamation Act. This article specifies that a reclamation permit cannot be granted unless certain conditions are met. The Court noted that these conditions are minimum requirements for what is fundamentally a discretionary decision by the Governor.

- Compliance with Article 4(1)(i) – "Proper and Rational in terms of National Land Use" (国土利用上適正且合理的ナルコト):

- This requirement means the purpose of the reclamation and the intended use of the reclaimed land must be proper and rational from a national land use perspective.

- The assessment "indispensably requires comprehensive consideration" of various factors, including the necessity and public nature of the reclamation project and its intended use, the utility gained from reclamation versus the utility lost, and other relevant circumstances. It does not require the proposed use to be the most proper or rational use, merely that it is proper and rational.

- A Governor's judgment that this requirement is met will not be deemed flawed unless it "lacks a factual basis or is clearly unreasonable in light of socially accepted ideas.

- In this case, the former Governor had considered the situation at Futenma Air Station, the history of negotiations between Japan and the U.S. for its return and the construction of an alternative facility, the fact that the new facility would be smaller than Futenma, and that flight paths would avoid residential areas. The Supreme Court found that this judgment by the former Governor did not lack a factual basis, nor was its content clearly unreasonable by social norms. Thus, the Original Permit did not violate Article 4(1)(i).

- Compliance with Article 4(1)(ii) – "Sufficient Consideration for Environmental Preservation and Disaster Prevention" (其ノ埋立が環境保全及災害防止二付十分配慮セラレタルモノナルコト):

- This requirement means that potential environmental and disaster prevention problems arising from the reclamation itself must be accurately identified, and appropriate measures to address them must be properly implemented.

- The assessment involves expert technical knowledge regarding the collection of environmental impact information, the appropriateness of predictions made based on that information, the thoroughness of examination of possible mitigation measures, and the proper evaluation of the effectiveness of such measures.

- Judicial review of a Governor's judgment on this requirement should be from the perspective of whether there is any "unreasonable point" in that expert technical judgment. This standard is similar to that established in the Ikata Nuclear Power Plant case for reviewing decisions based on specialized scientific expertise.

- In this case, the former Governor's assessment of compliance with this requirement was based on Okinawa Prefecture's own established review standards (which were not found to be particularly unreasonable). The former Governor, after considering responses from relevant municipalities and agencies, and replies from the Okinawa Defense Bureau, had examined the project based on expert technical knowledge, including the submitted Environmental Impact Assessment, and concluded that currently feasible construction methods and environmental protection measures were incorporated, and disaster prevention was sufficiently considered. The Supreme Court found no "particular unreasonable points" in the former Governor's judgment process or its content regarding this requirement. Thus, the Original Permit did not violate Article 4(1)(ii).

3. Illegality of the Revocation and Governor O's Subsequent Omission

Having found no illegality or impropriety in the Original Permit granted by the former Governor, the Supreme Court concluded:

- Governor O's ex officio revocation of the Original Permit (the Second Disposition), which was predicated on the assertion that the Original Permit was illegal, was itself an erroneous application of the Reclamation Act and therefore unlawful.

- This unlawful revocation constituted a case where "the processing of legally entrusted affairs by a prefecture... is in violation of laws or regulations," as stipulated in Article 245-7, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act.

- Consequently, Minister M's corrective instruction to Governor O, directing him to cancel his unlawful revocation, was itself lawful, and Governor O was under a legal obligation to comply with it.

- Given the passage of time (more than a week) since the corrective instruction was issued, the "reasonable period" for compliance under Article 251-7, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act had elapsed.

- Therefore, Governor O's failure to take the measure indicated in the corrective instruction (i.e., his failure to cancel his revocation of the Original Permit) constituted an illegal omission under Article 251-7, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act.

Key Takeaways and Analysis

The Supreme Court's 2016 decision in the Henoko permit revocation case offers significant clarifications on the judicial review of an agency's power to revoke its prior beneficial acts ex officio.

1. Focus on the Validity of the Original Administrative Act:

The most crucial takeaway is that when an agency revokes a prior beneficial disposition ex officio based on alleged flaws in that original disposition, the primary focus of judicial review is not on the discretion exercised in the act of revocation itself, but rather on the legality and propriety of the original disposition at the time it was made. If the original act was valid, the subsequent ex officio revocation based on its supposed flaws is impermissible and illegal.

2. Judicial Review of "Impropriety" alongside "Illegality":

The Court stated that the original disposition should be reviewed for "illegality or impropriety" ("違法等" - ihōtō). While traditionally, courts review administrative acts for "illegality" (including abuse of discretion), the explicit inclusion of "impropriety" (不当 - futō), which usually refers to a flaw not rising to the level of illegality but rather concerning the wisdom or suitability of a discretionary choice, raised academic discussion. However, in its actual review of the Original Permit's compliance with the Reclamation Act, the Supreme Court applied standards typically used for assessing illegality (i.e., whether the discretionary judgment lacked a factual basis, was clearly unreasonable by social norms, or had unreasonable points in its expert technical assessment). Thus, in practice, the review of "impropriety" in this instance did not seem to involve a fundamentally different or less stringent standard than that for illegality within the context of discretionary powers.

3. Application of Established Standards for Reviewing Discretion:

In assessing the Original Permit, the Supreme Court applied familiar standards for reviewing discretionary administrative decisions:

- For judgments involving broad policy considerations and balancing of various interests (like the "proper and rational national land use" requirement), a deferential standard was used, looking for a lack of factual basis or clear unreasonableness by social norms.

- For judgments requiring specialized scientific or technical expertise (like environmental impact assessments and disaster prevention measures), the Court adopted a standard similar to the Ikata Nuclear Power Plant case, examining whether there was any "unreasonable point" in the agency's expert technical judgment process and conclusions.

4. The Weight of Context:

Legal commentators have noted that the highly charged socio-political context of the Henoko base relocation and the expedited nature of these particular legal proceedings might have influenced the framing and outcome of this specific case. Therefore, caution may be warranted in over-generalizing all aspects of this judgment, particularly concerning ex officio revocation, to every type of administrative act or factual scenario.

5. Implications for Administrative Finality and an Agency's Power to Revoke:

This decision underscores that an administrative agency (including a successor in office) does not have unfettered power to unilaterally undo a prior beneficial administrative act, even if it believes the original act was flawed. The agency must be able to demonstrate that the original act was indeed illegal or improper at the time it was made, and this assessment will be subject to judicial scrutiny based on the standards applicable to that original act. This reinforces a degree of finality and reliability for recipients of beneficial administrative dispositions.

Conclusion

The 2016 Supreme Court judgment in the Henoko reclamation permit case provides important clarity on the legal principles governing the ex officio revocation of administrative acts in Japan. By firmly anchoring the legality of such a revocation to a judicial assessment of the validity of the original disposition, the Court reinforced the idea that an agency's power to undo its past beneficial actions is not absolute but is constrained by the actual presence of defects in that initial decision. The ruling also reaffirmed the established, albeit nuanced, standards for judicial review of administrative discretion involving both broad policy judgments and specialized technical assessments. While set against a unique and contentious backdrop, the decision offers significant guidance on the delicate balance between administrative flexibility, legal stability, and the rule of law.