Post-Parental Leave in Japan: Avoiding Discrimination and Protecting Return-to-Work Rights

TL;DR

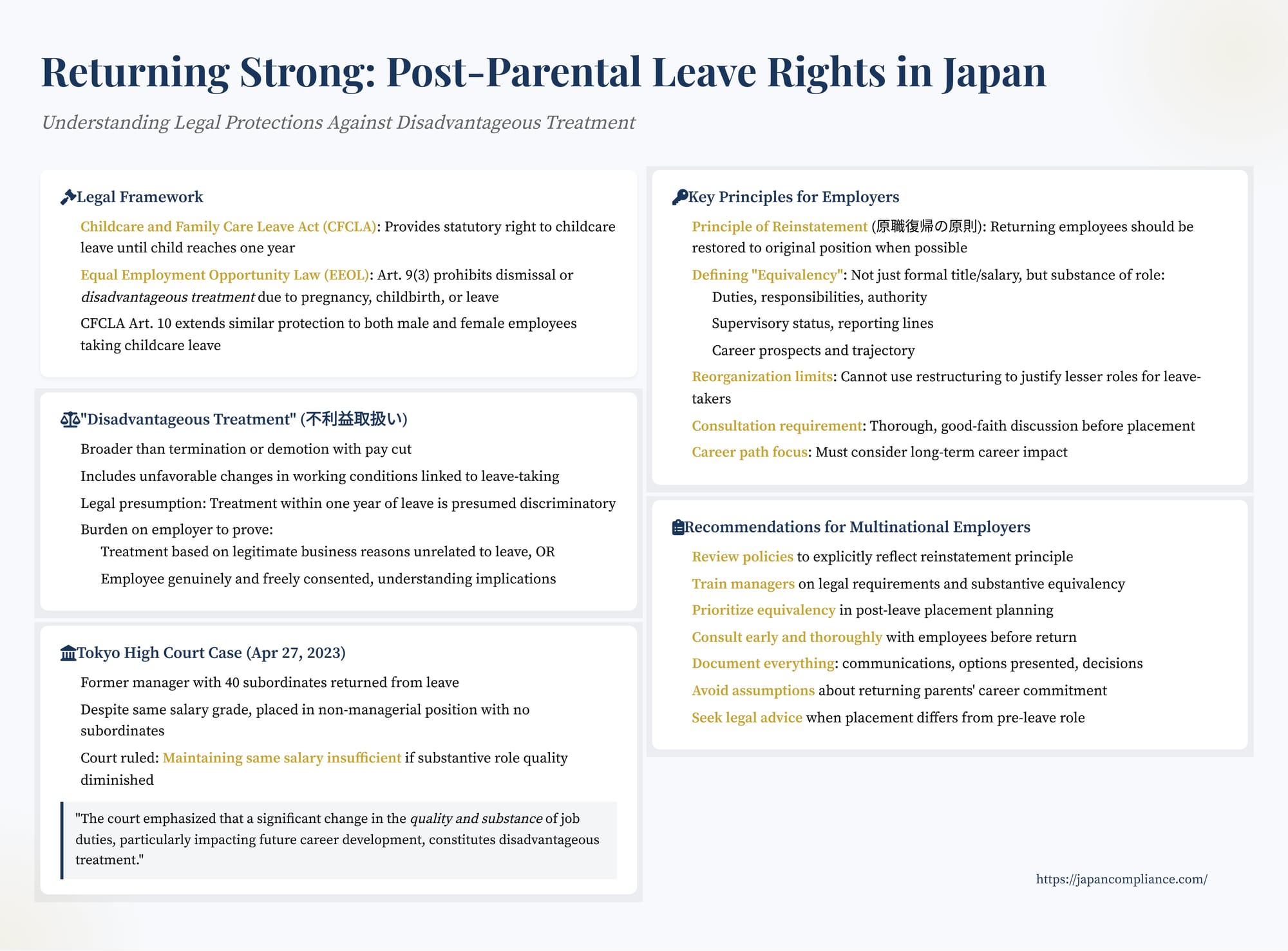

- Japan’s EEOL and CFCLA prohibit any disadvantageous treatment of employees who take parental leave.

- The Tokyo High Court (27 Apr 2023) ruled that placing a returning manager into an individual-contributor role—even with the same pay grade—was illegal discrimination.

- Equivalency is judged by duties, authority, and career trajectory, not merely salary.

- Employers must consult in good faith, document decisions, and obtain informed consent if the original role no longer exists.

- Multinationals should revise HR policies, train managers, and prioritise substantive reinstatement to minimise risk.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: Supporting Working Parents

- Understanding “Disadvantageous Treatment”

- The Tokyo High Court Case (April 27 2023): Substance Over Form

- Key Principles and Implications for Employers

- Practical Recommendations for Multinational Employers

- Conclusion

As businesses expand globally, navigating local labor laws, particularly those concerning parental leave and return-to-work rights, becomes paramount. Japan boasts a comprehensive legal framework designed to support working parents, offering rights to childcare leave and robust protections against discrimination related to pregnancy, childbirth, and leave-taking. However, misunderstandings or misapplication of these rules, especially regarding job placement upon return, can lead to significant legal risks for employers, including discrimination claims.

A key Tokyo High Court decision from April 27, 2023, sheds light on the nuances of "disadvantageous treatment" and underscores the importance employers must place on not just formal job titles or pay grades, but on the substantive nature of an employee's role and career path following parental leave. For multinational companies, particularly those with US headquarters managing Japanese subsidiaries or employees, understanding these principles is crucial for fostering a compliant and supportive work environment.

This article examines the legal landscape surrounding return-to-work rights after parental leave in Japan, analyzes the implications of the 2023 Tokyo High Court ruling, and offers practical considerations for employers.

The Legal Framework: Supporting Working Parents

Two primary laws govern parental leave and related anti-discrimination measures in Japan:

- Childcare and Family Care Leave Act (育児・介護休業法 - Ikuji Kaigo Kyūgyō Hō, "CFCLA"): This law provides employees (both male and female) with the statutory right to take childcare leave, generally until the child reaches the age of one (with potential extensions under certain conditions). It also mandates employer measures to support employees balancing work and family responsibilities.

- Act on Securing Equal Opportunity and Treatment between Men and Women in Employment (男女雇用機会均等法 - Danjo Koyō Kikai Kintō Hō, "EEOL"): This law prohibits discrimination based on sex. Crucially, Article 9, Paragraph 3 explicitly prohibits dismissing or otherwise treating a female worker disadvantageously on the grounds of pregnancy, childbirth, or requesting/taking statutory maternity or other related leave under the EEOL or the Labour Standards Act.

Furthermore, Article 10 of the CFCLA extends similar protection, prohibiting dismissal or other disadvantageous treatment on the grounds of an employee (male or female) applying for or taking childcare leave or family care leave.

Understanding "Disadvantageous Treatment" (不利益取扱い - Furieki Toriatsukai)

The concept of "disadvantageous treatment" (furieki toriatsukai) under both the EEOL and CFCLA is broader than just termination or demotion accompanied by a pay cut. It encompasses any unfavorable change in an employee's working conditions or employment status linked to their pregnancy, childbirth, or leave-taking.

Key points regarding disadvantageous treatment include:

- Broad Scope: It can include demotion, disadvantageous changes in job role or duties, detrimental transfers, refusal of training opportunities, negative performance evaluations, or forced retirement, among others.

- Causal Link: The core issue is whether the treatment is because of the pregnancy, childbirth, or leave.

- Legal Presumption: Japanese courts and administrative guidelines generally hold that if disadvantageous treatment occurs within a certain period (e.g., within one year) of pregnancy, childbirth, or taking leave, it is presumed to be linked to that event and therefore prohibited, unless the employer can prove otherwise.

- Burden of Proof: The burden falls on the employer to demonstrate either:

- The treatment was based on legitimate business reasons entirely unrelated to the pregnancy or leave, and these reasons would have led to the same treatment for any employee in similar circumstances, regardless of pregnancy/leave status.

- The employee genuinely and freely consented to the treatment, understanding its implications, and based on objective, reasonable circumstances (e.g., a mutually agreed-upon role change to accommodate specific needs, not simply reluctant acceptance of an employer's proposal).

The Tokyo High Court Case (April 27, 2023): Substance Over Form

This recent case provides critical clarification on what constitutes disadvantageous treatment in the context of post-leave placements, particularly when organizational changes occur during the leave period.

Case Summary (Anonymized):

- The employee was a female manager holding a leadership position (equivalent to Department Manager - 部長, buchō) with significant supervisory responsibilities (managing nearly 40 subordinates) at a large multinational company.

- She took a combination of sick leave, statutory maternity leave, and childcare leave.

- During her extended absence, the company underwent a reorganization, and her specific team was eliminated.

- Upon her return, the company placed her in a newly created "Account Manager" position. While this role carried the same internal salary grade (Job Band) as her previous managerial position, it involved entirely different duties focused on individual sales and telemarketing, with no subordinate staff.

- The employee had expressed her desire to return to a managerial role, equivalent to her pre-leave position, and did not request reduced working hours.

- She sued, arguing the placement constituted illegal disadvantageous treatment under the EEOL and CFCLA.

- The District Court initially sided with the company, finding the placement acceptable because the salary band was the same and viewing it as a standard personnel transfer necessitated by the reorganization.

The High Court's Reversal:

The Tokyo High Court overturned the lower court's decision, finding the placement illegal. Its reasoning provides crucial insights:

- Disadvantage Beyond Pay: The High Court explicitly rejected the notion that maintaining the same salary grade automatically precludes a finding of disadvantageous treatment. It emphasized that a substantial change in the quality and substance of job duties, particularly one negatively impacting future career development, constitutes disadvantageous treatment. Moving from managing a large team to an individual contributor role, even within the same pay band, was deemed a significant qualitative downgrade.

- Reason for Placement Matters: While acknowledging the business necessity arising from the team's elimination, the court scrutinized the reason for placing her specifically in a non-managerial role. It concluded that the decision was primarily driven by considerations related to her long absence due to leave and the company's perception of her potential childcare burdens, thus establishing the necessary causal link to her leave status.

- Lack of Free and Informed Consent: The court found that the company had not adequately consulted with the employee about her career aspirations or the implications of the new role. Her acceptance of the position was deemed reluctant rather than based on genuine free will informed by a thorough discussion of alternatives and career impacts. The standard for "free consent" requires more than just passive acceptance; it implies a situation where the employee, fully understanding the circumstances and options, voluntarily agrees to the change based on objective, reasonable grounds.

- Violation of Career Formation Interests: The court specifically noted that the placement disregarded the employee's "interest in career formation" (キャリア形成の利益 - kyaria keisei no rieki). By placing her in a role that fundamentally differed from her previous managerial trajectory and aspirations, the company negatively impacted her long-term career development prospects.

- Abuse of Personnel Rights: Consequently, the court ruled the placement was prohibited disadvantageous treatment under EEOL Article 9(3) and CFCLA Article 10. It further characterized the company's actions as an abuse of its personnel management rights, contrary to public order.

Key Principles and Implications for Employers

This ruling reinforces and clarifies several key principles regarding return-to-work rights in Japan:

- The Principle of Reinstatement (原職復帰の原則 - Genshoku Fukki no Gensoku): While not an absolute guarantee enshrined in statute for all leave types in exactly the same way, the underlying principle strongly supported by anti-discrimination laws (EEOL, CFCLA) is that employees returning from protected leave should, whenever possible, be returned to their original position. If the original position no longer exists due to legitimate business reasons (like a genuine reorganization), the employee must be placed in a truly equivalent position.

- Defining "Equivalency": Equivalency is judged not just by formal markers like job title or salary grade, but by the substance of the role. This includes factors like duties, responsibilities, level of authority (including supervisory status), reporting lines, working conditions, location (where relevant), and, importantly, career prospects and alignment with the employee's pre-leave career trajectory. A role without former supervisory duties is rarely considered equivalent to a managerial one.

- Reorganization is Not a Blank Check: While employers can reorganize, they cannot use restructuring as a justification to place returning employees into substantively lesser roles simply because they took leave. The specific placement decision must be demonstrably free from discriminatory motive linked to the leave itself.

- Consultation is Key: If reinstatement to the original or a clearly equivalent role is impossible, employers must engage in thorough, good-faith consultations with the returning employee before finalizing a placement. This involves explaining the situation transparently, exploring available options, discussing the nature and responsibilities of potential alternative roles, and considering the employee's input and career aspirations.

- Obtaining Genuine Consent: If the only available roles differ significantly from the original, particularly if they could be seen as less advantageous in substance or career potential, obtaining the employee's informed, voluntary, and uncoerced consent is critical to mitigate legal risk. This requires full disclosure of the role's nature and potential career implications. Relying on an employee's reluctant acceptance under pressure is insufficient.

- Focus on Career Path: The High Court's emphasis on "career formation interests" signals that employers need to consider the potential long-term career impact when assigning roles after leave, striving to maintain the employee's developmental trajectory where feasible.

Practical Recommendations for Multinational Employers

For US and other multinational companies employing staff in Japan, adhering to these principles is vital:

- Review Policies: Ensure internal HR policies and return-to-work procedures explicitly reflect the principle of reinstatement to the original or a truly equivalent position, defining equivalency broadly to include substantive duties and career path.

- Train Managers: Train HR personnel and line managers on the legal requirements of the EEOL and CFCLA, the definition of disadvantageous treatment, the importance of substantive equivalency, and the necessity of sensitive, thorough consultations before finalizing post-leave placements.

- Prioritize Equivalency: When planning for an employee's return, make every effort to identify the original or a genuinely equivalent position. Document the assessment process used to determine equivalency.

- Consult Early and Thoroughly: If an equivalent position is arguably unavailable due to legitimate restructuring, initiate consultations with the employee well in advance of their return date. Discuss the situation openly, present available options with full details, and genuinely consider the employee's feedback and preferences.

- Document Everything: Meticulously document all communications, consultations, options presented, decisions made (and the objective business reasons for them), and any agreements reached with the employee regarding their post-leave placement. Signed documentation confirming informed consent is highly advisable if a non-equivalent role is agreed upon.

- Avoid Assumptions: Do not assume an employee returning from leave (especially childcare leave) desires a less demanding role or is less committed to their career. Decisions must be based on individual consultation, not stereotypes.

- Seek Legal Advice: If considering a placement that differs significantly from the employee's pre-leave role, or if the employee expresses dissatisfaction, seek advice from legal counsel experienced in Japanese labor law before finalizing the placement.

Conclusion

Japan provides strong legal protections for employees taking parental leave, prohibiting discriminatory or disadvantageous treatment upon their return. The 2023 Tokyo High Court ruling serves as a critical reminder that ensuring compliance requires more than just maintaining formal job titles or pay grades. Employers must focus on the substantive nature of the role, the employee's career trajectory, and engage in genuine consultation to ensure any deviation from reinstatement to an equivalent position is legally defensible, ideally through the employee's free and informed consent. For multinational companies, integrating these principles into their Japanese HR practices is essential for minimizing legal risk and fostering a workplace culture that truly supports working parents.

- Workforce Management in Japan: Tackling Indirect Discrimination and the New Freelance Act

- A Century-Old Rule Challenged: Japan's Supreme Court on Women’s Remarriage Ban and Paternity Presumptions

- Too Late to Annul? Japan's Supreme Court on Bigamous Marriages Already Ended by Divorce

- MHLW – Promotion of Balancing Work and Family (English)