Retroactive Tax Law Changes: Japan's Supreme Court on Balancing Public Interest and Legal Stability

Judgment Date: September 22, 2011

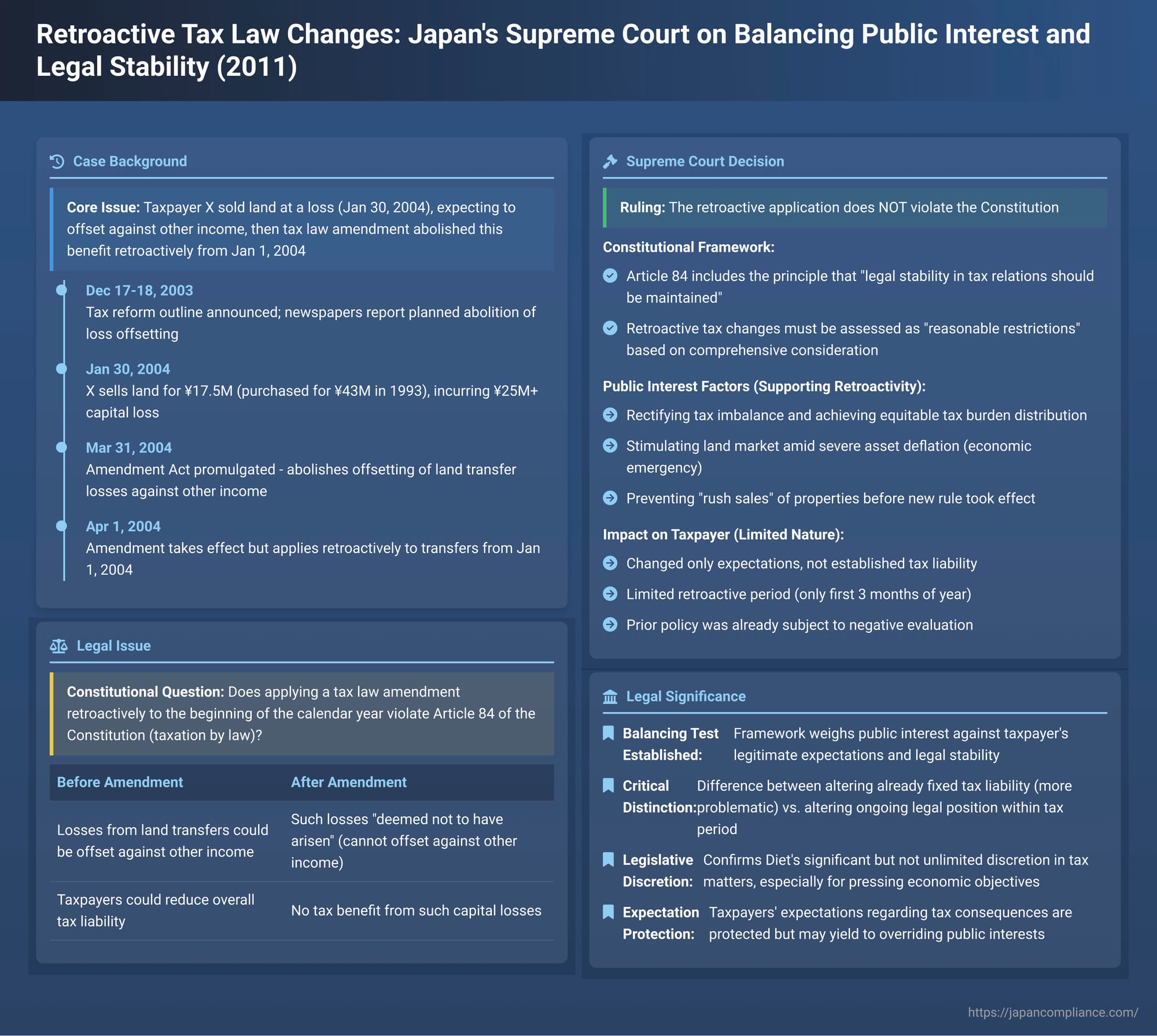

In a significant ruling for Japanese tax law and constitutional interpretation, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the constitutionality of a mid-year tax law amendment that was applied retroactively to the beginning of that same calendar year. The case involved a taxpayer who suffered a capital loss from a land transaction, expecting to offset this loss against other income, only to find that a subsequently enacted law, applied retroactively, abolished this tax benefit. The Court upheld the retroactive application, providing a detailed framework for balancing the public interest against the impact on taxpayers' legal stability.

Background of the Dispute: A Land Sale and an Unexpected Tax Law Change

The appellant, X, purchased a parcel of land in 1993 for 43 million yen. On January 30, 2004, X entered into a contract to sell this land for 17.5 million yen, with the transfer to the buyer completed on March 1, 2004. This sale resulted in a substantial capital loss for X, amounting to over 25 million yen ("the subject capital loss").

In September 2005, X filed a final income tax return for the 2004 tax year. Subsequently, on November 16, 2005, X filed a request for correction (a claim for a refund), asserting that by offsetting the subject capital loss against other income (such as employment income and miscellaneous income), there should be a tax refund of 1,369,400 yen.

However, the relevant tax office, on February 17, 2006, issued a notice stating that there was no reason to grant the correction. X pursued administrative appeals (an objection and a request for examination), but both were dismissed. Consequently, X initiated a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the tax office's notice.

The crux of the dispute lay in an amendment to the Special Taxation Measures Act (Act No. 14 of 2004, hereinafter "the Amending Act").

- Before the Amendment (Former Special Taxation Measures Act, Article 31): For individuals, income from the "long-term transfer" of land or buildings (defined as assets owned for over five years as of January 1 of the year of transfer) was subject to separate taxation. For transfers made between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2003, the income tax rate on such long-term capital gains was 20%. Crucially, if a loss arose from such a long-term transfer, the former law permitted this loss to be offset against other categories of income (a practice known as "損益通算" - son'eki tsusan, or profit and loss offsetting).

- After the Amendment (Amended Special Taxation Measures Act, Article 31): The Amending Act brought two key changes. While the income tax rate on long-term capital gains was reduced to 15%, the provision allowing for the special deduction from such gains was abolished. More significantly for this case, if a loss was incurred from a long-term capital gain transaction, the amended law stipulated that, for the purpose of applying income tax laws, such a loss was deemed not to have arisen. This effectively abolished the offsetting of losses from long-term capital gains on land and buildings against other income (hereinafter "the subject abolition of loss offsetting").

- Effective Date and Retroactive Application: The Amending Act was promulgated on March 31, 2004, and officially came into force on April 1, 2004. However, a supplementary provision within the Amending Act (Article 27, Paragraph 1; specifically the part concerning the abolition of loss offsetting is referred to as "the Subject Supplementary Provision") controversially stipulated that the amended Article 31 would apply to transfers of land or buildings made on or after January 1, 2004.

X's land sale contract was signed on January 30, 2004, and the transfer completed on March 1, 2004 – both dates falling within this period of retroactive application (i.e., after January 1, 2004, but before the Amending Act came into force on April 1, 2004).

The Path to the Amendment

The decision to amend the tax law was not made in a vacuum. The judgment outlines the following timeline leading to the change:

- From 2000 onwards, government tax councils and study groups had pointed out the need to review tax rules, including limiting the offsetting of losses from highly speculative investment activities against income from business activities, and creating a more market-neutral tax system in light of falling land prices.

- December 17, 2003: The ruling coalition parties' "Fiscal Year 2004 Tax Reform Outline" was finalized. It included a policy to abolish the offsetting of losses from long-term capital gains for income tax purposes from the 2004 tax year onwards.

- December 18, 2003: Newspapers reported the contents of this tax reform outline, including the planned abolition.

- January 16, 2004: The Japanese government's official "Fiscal Year 2004 Tax Reform Outline," consistent with the coalition's plan, was approved by the Cabinet.

- February 3, 2004: A bill to amend the Income Tax Act and other laws, incorporating the subject abolition of loss offsetting, was submitted to the National Diet.

- March 26, 2004: The bill was passed by the Diet.

- March 31, 2004: The bill was promulgated as the Amending Act.

- April 1, 2004: The Amending Act came into force.

The Court also noted that immediately after the newspaper reports in December 2003 about the planned abolition, websites operated by investment consultants, real estate companies, and tax accounting firms began publishing articles advising the sale of depreciated real estate within the 2003 calendar year.

X's claim was dismissed by both the court of first instance and the appellate court, leading to this appeal to the Supreme Court. X argued that the retroactive application of the Amending Act to his transaction was a detrimental retroactive law that violated Article 84 of the Constitution (which mandates taxation by law).

The Supreme Court's Constitutional Framework

The Supreme Court began by acknowledging the legal complexities. While an individual's income tax liability for a given year is finalized at the end of that calendar year (under Article 15, Paragraph 2, Item 1 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes), meaning the Amending Act didn't retroactively change an already established tax liability for 2004, the Court recognized that:

- Transactions like long-term capital asset sales are typically made based on the existing tax laws.

- Income tax is levied on the accumulation of individual income items over a calendar year.

- Therefore, applying a mid-year amendment retroactively to transactions completed before the amendment's enforcement can indeed alter a taxpayer's legal position under the tax laws and affect legal stability in tax relations.

The Court then laid out its framework for assessing the constitutionality of such retroactive applications:

- Article 84 and Legal Stability: Article 84 of the Constitution mandates that taxation requirements and the procedures for assessment and collection must be clearly prescribed by law. The Court interpreted this to include the principle that legal stability in tax relations should be maintained. (Referencing a 2006 Grand Bench decision, the Asahikawa City NHI case).

- Analogy to Property Rights: The Court drew an analogy to situations where the content of property rights, once established by law, is subsequently altered by a new law, potentially affecting legal stability. In such cases, the constitutionality of the alteration is judged by comprehensively considering various factors:

- The nature of the property right in question.

- The degree to which its content is being changed.

- The nature of the public interest sought to be protected by the change.

The ultimate determination is whether the change can be accepted as a reasonable restriction on that property right. (Referencing a 1978 Grand Bench decision).

- Application to Tax Law Changes: The Court reasoned that this same analytical framework should apply when a taxpayer's legal position under tax law is altered by a mid-year change in tax legislation that is applied from the beginning of that calendar year. Even though such changes in tax law might have varying impacts on economic activities depending on their specific subject, content, and extent, they ultimately affect the financial interests of citizens. Therefore, their reasonableness should be judged by a comprehensive consideration of relevant factors, just as with changes to property rights.

- The Core Test: Consequently, whether the Subject Supplementary Provision (which applied the abolition of loss offsetting retroactively to January 1, 2004) violates the spirit of Article 84 must be determined by:

- Comprehensively evaluating all relevant circumstances.

- Deciding whether the impact of such a mid-year tax law change and its retroactive application on legal stability in tax relations can be accepted as a reasonable restriction on the taxpayer's legal position under the tax law.

Applying the Framework: Balancing Public Need and Taxpayer Expectation

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to the specific facts of X's case.

(A) The Public Interest and Legislative Purpose

The Court identified several key public interests behind the Amending Act and its retroactive application:

- Rectifying Tax Imbalance: The amendment aimed to resolve an imbalance where gains from long-term land transfers were subject to separate taxation, while losses from such transfers could be offset against other income. The change sought to achieve a more equitable distribution of the tax burden.

- Stimulating the Land Market: Coupled with a reduction in the tax rate on long-term capital gains, the amendment was designed to promote land transactions at prices reflecting their appropriate use value, thereby revitalizing the land market. This was seen as a measure to counteract the prolonged decline in real estate prices ("asset deflation") which was having a severe negative impact on the Japanese economy. These measures were envisioned as an integrated package requiring urgent implementation.

- Preventing Rush Sales: The retroactive application of the loss offsetting abolition to January 1, 2004, was intended to prevent a surge of "rush sales" of properties at low prices. Such sales would have been motivated by the desire to realize tax losses before the new rule took effect, thereby undermining the broader legislative objectives. The Court found the risk of such rush sales to be concrete, evidenced by the immediate online advice from consultants and real estate firms to sell depreciated properties within 2003 following news of the proposed policy change in December 2003.

Given the serious economic situation caused by prolonged asset deflation, the Court concluded that applying the amended provisions from the beginning of the calendar year was based on a specific public interest requirement.

(B) The Nature and Extent of the Impact on the Taxpayer's Position

The Court then assessed how the retroactive change affected X:

- Nature of the Altered Position: What was changed by the Amending Act was not X's tax liability itself (which crystallizes at the end of the calendar year), but rather X's expectation of being able to offset a specific loss arising from a particular transaction at the year's end to achieve a tax burden reduction.

- Uncertainty of Expectation: Whether this expectation would actually result in a tax benefit depended on X's overall income and losses for the entire calendar year 2004. The Court noted that the earlier in the year a transaction occurs, the more uncertain the final tax outcome based on that transaction becomes.

- Legislative Discretion and Policy Shift: Tax laws are established based on the legislature's discretionary judgment, which considers comprehensive policy (fiscal, economic, social) and highly specialized technical factors. The taxpayer's expectation was founded on a system created by such discretionary judgment. By the time the Amending Act was being drafted, the specific provision allowing loss offsetting for long-term capital gains was already subject to negative policy evaluations, viewed as creating an imbalance and needing correction to ensure fair taxation.

- Fairness and Limited Duration: Applying the Amending Act from January 1, 2004, ensured that the tax rules were applied consistently for the entire calendar year, promoting fairness across all transactions within that year. Moreover, the period of actual retroactivity (from January 1 to March 31, 2004, before the law's enforcement on April 1) was limited to the first three months of the calendar year.

- No Aggravation of Established Liability: While X lost the anticipated tax reduction, X was not subjected to an increased tax burden on an already established and finalized tax liability. The change did not impose a penalty or aggravate a past obligation.

The Supreme Court's Conclusion

After comprehensively considering these various factors—the specific public interest requiring the retroactive application, and the nature and limited extent of the impact on the taxpayer's pre-existing legal position—the Supreme Court concluded:

The Subject Supplementary Provision, which applied the abolition of loss offsetting for long-term capital gains (as per the Amended Special Taxation Measures Act) to transfers made on or after January 1, 2004, should be accepted as a reasonable restriction on the taxpayer's aforementioned legal position under the tax law.

Therefore, the Court held that the Subject Supplementary Provision did not violate the spirit of Article 84 (taxation by law) or Article 30 (duty to pay taxes as provided by law) of the Constitution. The judgment of the lower court dismissing X's claim was affirmed, and the appeal was dismissed.

Significance of the Ruling

This 2011 Supreme Court decision is of considerable importance as it clarifies the constitutional framework for evaluating "intra-year retroactive tax legislation" in Japan. It eschews a per se prohibition on such retroactivity, instead establishing a balancing test. This test weighs the public interest motivating the legislative change against the degree of infringement on the taxpayer's legitimate expectations and the overall stability of tax relations.

The Court's careful distinction between altering an already fixed tax liability and altering a taxpayer's ongoing legal position and expectations within a tax period is a key element. While the terms "retroactive legislation" or "predictability" are not explicitly central to the Court's core reasoning, these concepts are inherently part of the "legal stability" that Article 84 is deemed to protect. The ruling confirms the Diet's significant, though not unlimited, discretion in tax matters, especially when addressing pressing economic or social policy objectives. It signals that taxpayers' expectations regarding future tax consequences of their current actions, while protected, may yield to overriding public interests if the restriction is deemed reasonable under a comprehensive assessment of all circumstances.