Retirement Allowances (Taishokukin) in Japan: Legal Nature, Tax Implications, and Restrictions on Forfeiture

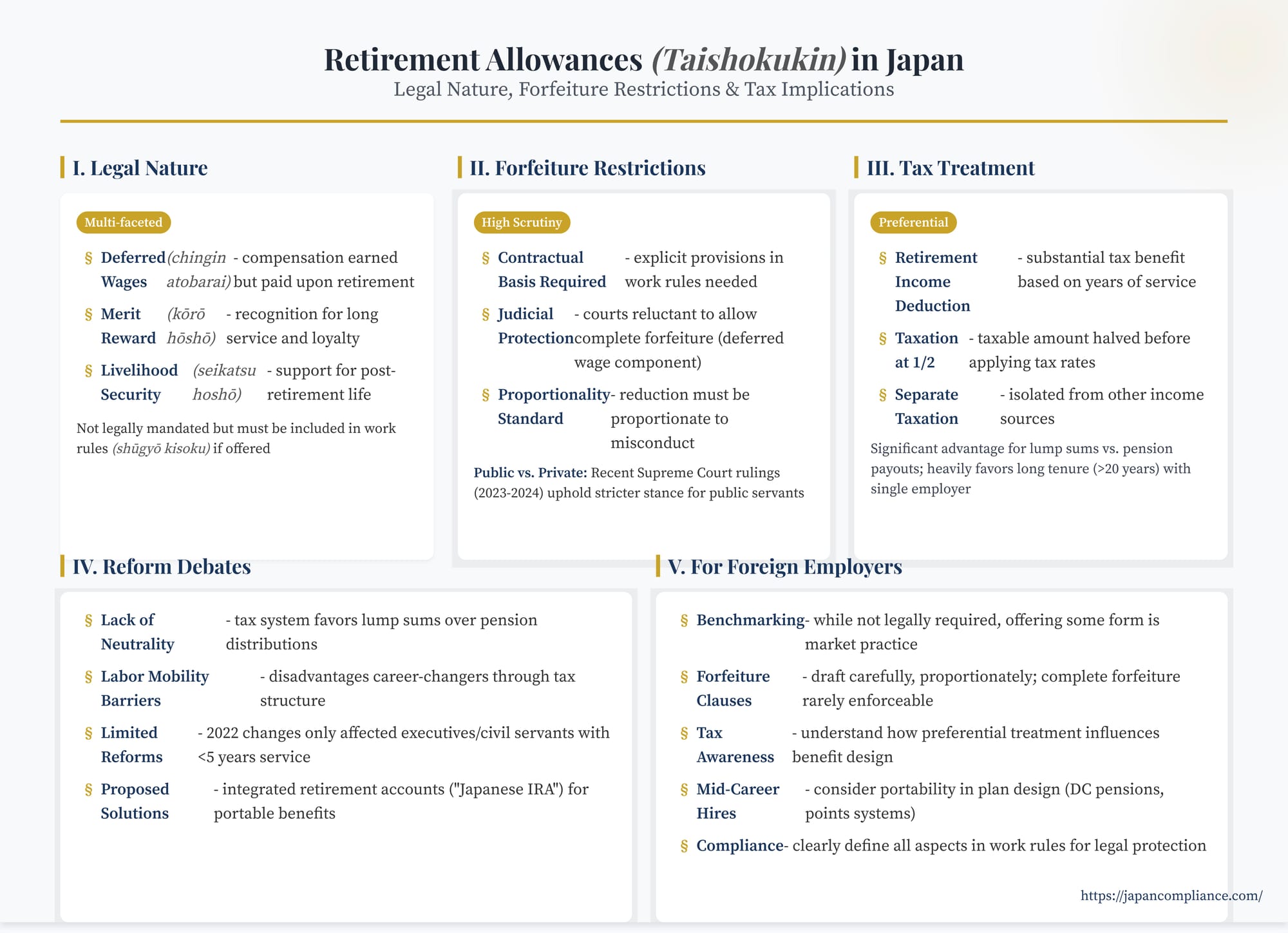

TL;DR: Taishokukin, Japan’s lump-sum retirement allowance, is a hybrid of deferred wages, merit reward, and livelihood security. Courts strictly limit forfeiture, while generous tax rules reward long-tenure lump sums—yet reform debates question their fit for a mobile labor market.

Table of Contents

- What is Taishokukin? Legal Nature and Common Forms

- Restrictions on Forfeiture or Reduction

- Divergence? The Public Sector Approach

- Preferential Tax Treatment: Incentivizing Long-Term Savings

- Current Issues and Reform Debates

- Implications for Foreign Employers in Japan

- Conclusion: A System in Transition?

Retirement allowances, known in Japan as taishokukin (退職金) or taishokuteate (退職手当), are a deeply ingrained feature of the Japanese compensation landscape. Traditionally linked with the country's model of long-term, often lifetime, employment, these payments – typically made as a lump sum or through corporate pensions upon retirement or separation – serve multiple functions, including rewarding long service, providing post-retirement financial security, and acting as a form of deferred compensation.

For international companies operating in Japan, understanding the nuances of taishokukin is essential for designing competitive compensation packages, managing employee separations, and ensuring legal and tax compliance. This involves appreciating their unique legal status, the significant tax advantages they often receive, and the legal limits on an employer's ability to withhold payment, even in cases of employee misconduct. Furthermore, ongoing discussions about labor market reforms are bringing the structure and tax treatment of taishokukin into sharper focus.

What is Taishokukin? Legal Nature and Common Forms

Unlike some aspects of compensation, the provision of a retirement allowance is not mandated by Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA). However, it is a widespread practice, particularly among larger companies and for "regular" employees (seishain) on indefinite-term contracts. When an employer does establish a retirement allowance system, the rules governing eligibility, calculation methods, and payment timing must be clearly stipulated in the company's work rules (shūgyō kisoku) or a collective bargaining agreement (LSA Art. 89). Once defined, these payments are generally considered "wages" under the LSA (Art. 11), meaning employers are legally obligated to pay them according to the established rules.

Japanese courts and legal scholars generally recognize taishokukin as having a multifaceted legal nature:

- Deferred Wages (chingin atobarai - 賃金後払い): A significant portion is often viewed as wages earned throughout the employment period but paid out upon retirement. This view is supported by calculation methods frequently based on the employee's final base salary and years of service.

- Merit Reward / Long-Service Reward (kōrō hōshō - 功労報償): Taishokukin often increases progressively, sometimes exponentially, with longer tenure. Higher amounts or specific eligibility criteria might also be linked to an employee's rank or contributions, reflecting a reward for long-term loyalty and service. Different payout rates might apply depending on the reason for retirement (e.g., mandatory retirement vs. voluntary resignation vs. disciplinary dismissal).

- Livelihood Security (seikatsu hoshō - 生活保障): Particularly for lump-sum payments, taishokukin is often seen as a crucial source of funds for supporting the employee's post-retirement life, bridging the gap until public pension payments begin or supplementing them thereafter.

While the traditional model often involves a final-salary-based lump sum, variations exist and are becoming more common, including:

- Points-Based Systems: Accumulating points based on factors like rank, years of service, and performance, which translate into a monetary value at retirement.

- Corporate Pension Plans (kigyō nenkin - 企業年金): Including Defined Benefit (DB) and Defined Contribution (DC) plans, offering retirement income streams instead of, or alongside, lump sums.

- Pre-Paid Options: Some systems allow employees to opt for higher current salaries in lieu of accumulating future retirement benefits.

The specific design of the plan can influence the perceived weight of each legal characteristic (deferred wage vs. reward).

Restrictions on Forfeiture or Reduction

A critical issue for employers is the extent to which they can refuse to pay or reduce the amount of taishokukin if an employee is dismissed for cause, particularly through a disciplinary dismissal (chōkai kaiko - 懲戒解雇) for serious misconduct.

- Contractual Basis Required: Any forfeiture or reduction must be explicitly provided for in the work rules or relevant plan documents that form part of the employment contract. Without such a provision, the employer generally cannot withhold earned taishokukin.

- Judicial Scrutiny (Private Sector): Even when forfeiture clauses exist, Japanese courts scrutinize their application strictly. Reflecting the mixed legal nature of taishokukin:

- Complete Forfeiture is Difficult: Due to the strong "deferred wage" component, courts are very reluctant to uphold the complete forfeiture of retirement benefits, even for serious misconduct leading to disciplinary dismissal. The rationale is that the employee has already earned a portion of this compensation through past service.

- Partial Reduction Permitted: Courts often find that partial reductions are permissible, particularly concerning the "merit reward" aspect. If an employee's misconduct is severe enough to significantly diminish or negate their contributions and loyalty to the company, reducing or eliminating the merit-based portion of the taishokukin may be considered reasonable.

- Proportionality is Key: The central test is whether the forfeiture or reduction is proportionate to the severity of the employee's misconduct. Courts typically hold that denying all retirement benefits requires misconduct so egregious that it effectively "wipes out" or cancels the value of the employee's entire history of service to the company. This is a very high threshold.

- Examples: In cases involving off-duty drunk driving leading to disciplinary dismissal – a serious offense often warranting dismissal itself – courts have frequently overturned complete forfeiture of taishokukin in the private sector, often ordering the payment of a significant portion (e.g., 70%, 50%), reasoning that while the misconduct warranted discipline, it didn't necessarily erase the value of decades of prior service (relevant for the deferred wage component).

Divergence? The Public Sector Approach

Interestingly, the treatment of retirement allowances for public servants (kōmuin) in Japan shows potentially diverging trends, despite ongoing efforts to align public and private sector practices.

- Statutory Basis: Public servant retirement allowances (taishokuteate) are governed by statute (e.g., the National Public Servant Retirement Allowance Act).

- Emphasis on Merit Reward: Historically and legally, the "merit reward" aspect has often been emphasized more strongly for public servants compared to the private sector.

- Shift to Discretionary Reduction: While automatic full forfeiture upon disciplinary dismissal (chōkai menshoku - 懲戒免職) was once standard, legal reforms (e.g., a 2008 revision to the national law) introduced a system where the relevant agency has discretion to decide whether to withhold payment, and how much, based on factors like the nature of the misconduct, the employee's position, and the impact on public trust (Art. 12(1)(i) of the Act).

- Recent Supreme Court Rulings: Despite the move towards discretion, two significant Supreme Court decisions in 2023 and 2024 (e.g., Miyagi Prefecture v. Teacher, June 27, 2023; Otsu City v. Employee, June 27, 2024 – anonymized references) upheld the complete forfeiture of retirement allowances for public servants dismissed for off-duty drunk driving involving property damage. These rulings emphasized the severity of the misconduct and the profound damage to public trust inherent in such acts by public officials, seemingly giving less weight to the deferred wage/livelihood security aspects compared to common private sector outcomes. Both decisions included strong dissenting opinions arguing for proportionality and consistency.

While these public sector rulings don't directly bind private employers, they highlight a potential tension in how forfeiture is viewed depending on the employment context and the perceived importance of public trust.

Preferential Tax Treatment: Incentivizing Long-Term Savings

A major characteristic of the Japanese taishokukin system is the highly preferential tax treatment afforded, particularly to lump-sum payments. This treatment, designed under the traditional long-term employment model, significantly reduces the tax burden compared to regular salary income. Key features under the Income Tax Act (Shotoku Zeihō) include:

- Retirement Income Deduction (Taishoku Shotoku Kōjo): A substantial deduction is applied before calculating taxable retirement income. The amount of the deduction is based directly on the employee's years of service with the employer. Crucially, the formula provides a much larger deduction per year of service after the 20-year mark. This structure heavily incentivizes long-term employment with a single company and often results in average or even substantial lump-sum retirement allowances being entirely or largely tax-free.

- Taxation at 1/2: After applying the retirement income deduction, the remaining taxable amount is halved before tax rates are applied (Art. 30(2)). This aims to mitigate the effect of progressive tax rates on income accumulated over many years but received in a single tax year.

- Separate Taxation: Taxable retirement income is taxed separately from other sources of income (like salary or investment income), preventing it from pushing other income into higher tax brackets (Art. 22(1), Art. 30(1)).

Contrast with Corporate Pensions: While corporate pension payments also receive a deduction (the "public pension deduction," kōteki nenkin tō kōjo), they are generally taxed as miscellaneous income (zatsu shotoku), aggregated with other income, and subject to standard progressive rates. This usually results in a higher overall tax burden compared to receiving the equivalent amount as a lump-sum taishokukin, especially for larger benefit amounts.

Current Issues and Reform Debates

The traditional taishokukin system, particularly its tax treatment, faces criticism for being misaligned with modern labor market trends and policy goals:

- Lack of Neutrality: The significant tax advantage for lump sums over pension payouts creates a strong incentive for employees to choose lump-sum distributions, even if an annuity might provide better long-term retirement security. This distorts choice and may not align with optimal retirement planning.

- Discouraging Labor Mobility: The structure of the retirement income deduction, heavily rewarding continuous service exceeding 20 years with one employer, disadvantages individuals who change jobs multiple times throughout their careers. Even if their total working life is long, they may receive multiple smaller retirement allowances, each subject to a less generous deduction (primarily based on the shorter tenure at each firm), resulting in a higher overall tax burden compared to someone with the same total career length at a single company. This structure is seen as a potential impediment to the labor market fluidity the government now seeks to promote.

- Limited Scope of Recent Reforms: While acknowledging these issues, recent tax reforms have been limited. Changes implemented around 2022 primarily addressed perceived excesses by removing the 1/2 taxation benefit for the portion of taishokukin exceeding the deduction that is over JPY 3 million, but only for directors and civil servants with five years of service or less. The fundamental structure favoring long-term single-employer tenure for general employees remains largely intact.

- Proposed Solutions: Academics and policy groups continue to propose reforms aimed at greater neutrality and fairness. One prominent idea involves creating integrated, tax-advantaged retirement accounts (sometimes dubbed a "Japanese IRA" or JIRA) where various forms of retirement savings (lump sums, pension contributions, potentially salary deferrals, individual savings) could be accumulated and taxed uniformly upon withdrawal, regardless of the source or timing of contributions relative to employment changes. Such proposals aim to decouple retirement savings tax benefits from specific employment patterns.

Implications for Foreign Employers in Japan

Understanding the taishokukin system is vital for foreign companies operating in Japan:

- Benchmarking and Design: While not legally required, offering some form of retirement benefit (lump sum or pension) is common practice and often necessary to attract and retain talent, especially for regular employee positions. Benchmarking against local industry standards is important.

- Forfeiture Clauses: If including clauses for forfeiture or reduction upon disciplinary dismissal, ensure they are carefully drafted, reasonable, proportionate, and clearly communicated in the work rules. Be aware that complete forfeiture is highly likely to be challenged successfully by employees in court.

- Tax Impact Awareness: Understand how the preferential tax treatment of lump-sum taishokukin influences employee preferences and the net value of different benefit designs.

- Mobility and Mid-Career Hires: Recognize that traditional taishokukin structures based on long tenure might be less attractive to mid-career hires or employees who anticipate future job changes. Consider plan designs (e.g., DC pensions, points systems) that offer greater portability.

- Funding and Accounting: Ensure appropriate funding mechanisms and accounting treatment for retirement benefit obligations are in place.

- Compliance: Clearly define all aspects of the retirement benefit plan in the work rules and ensure consistent application.

Conclusion: A System in Transition?

Japan's taishokukin system is a complex blend of deferred compensation, reward for loyalty, and post-retirement security, deeply rooted in the nation's traditional employment practices. Its dual legal nature leads to specific constraints on forfeiture, particularly in the private sector, where courts generally protect the deferred wage component even in cases of disciplinary dismissal. The system's highly preferential tax treatment for lump-sum payments, designed for an era of lifetime employment, provides significant benefits to long-serving employees but faces criticism for lacking neutrality and potentially hindering labor market mobility.

While recent Supreme Court decisions on public servant cases suggest a stricter stance on forfeiture in that context, and policy debates continue regarding tax reforms to better align with diverse career paths, the core features of the taishokukin system remain largely intact for now. For businesses operating in Japan, navigating this requires understanding its legal underpinnings, tax advantages, cultural significance, and the ongoing tensions between tradition and the push for a more flexible labor market. Designing effective, compliant, and attractive retirement benefit strategies necessitates careful consideration of these multifaceted factors.

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- Employee Dismissals in Japan: Membership vs. Job-Based Models and Termination Rules

- Engaging Japan’s Freelance Workforce: The New Freelance Protection Act

- National Tax Agency — Guide to Retirement Income Taxation

https://www.nta.go.jp/publication/pamph/koho/kurashi/html/02_4.htm