Retained Title and Trespassing Cars: Who is Responsible for Removal in Japan?

Date of Judgment: March 10, 2009

Case Name: Action for Removal of Vehicle and Vacant Possession of Land, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

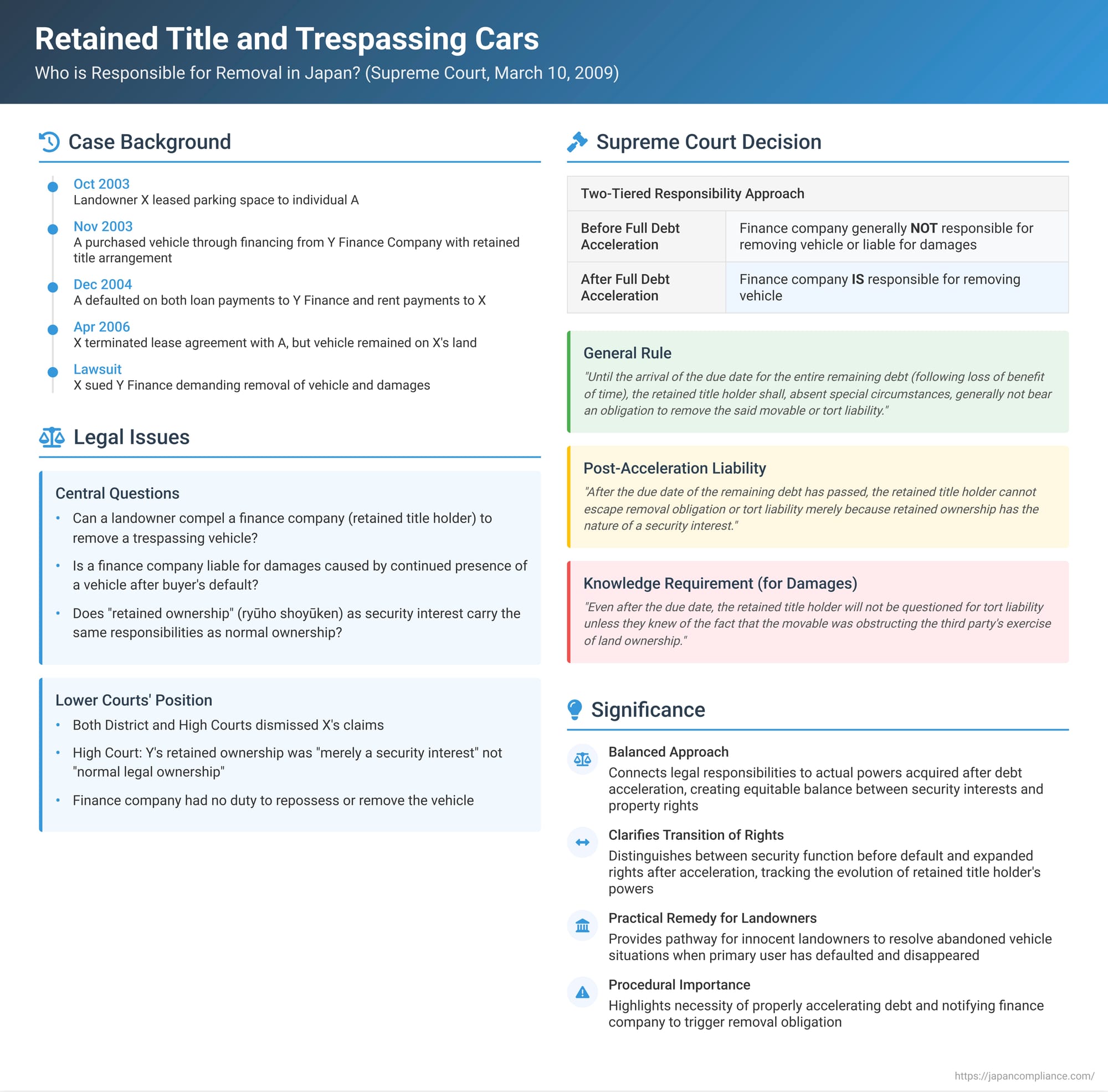

In vehicle financing, it's common for credit companies (shinpan kaisha) or dealers to "retain title" (ownership) to a vehicle until the buyer completes all installment payments. This "retained ownership" (ryūho shoyūken) serves as a security interest for the financier. But what happens if the buyer defaults on their loan, the vehicle is left trespassing on a third party's land (like an unpaid parking space), and the buyer then abandons the situation? Can the landowner compel the finance company, as the retained title holder, to remove the vehicle and compensate for the unauthorized occupation? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this increasingly common and complex issue in a significant judgment on March 10, 2009, establishing a two-tiered approach to the finance company's responsibility.

The Facts: A Parking Lease, a Car Loan, Defaults, and an Abandoned Vehicle

The case arose from a straightforward vehicle financing arrangement that went awry:

- The Parking Lease: In October 2003, X, a landowner, leased a parking space on their property ("the Land") to an individual, A, for the purpose of parking A's vehicle ("the Vehicle"). This was the "Lease Agreement."

- The Vehicle Financing: In November 2003, A entered into a "Loan Agreement for Substitute Payment" (tatekaebarai keiyaku) with Y Finance to purchase the Vehicle from a car dealer. This was a typical "individual credit purchase arrangement" (kobetsu shin'yō kōnyū assen), a common form of installment sale financing in Japan.

- Under this agreement:

- Y Finance would pay the vehicle's purchase price directly to the car dealer on A's behalf. A, in turn, was obligated to repay Y Finance the advanced sum in 60 monthly installments (the "Retained Ownership Debt").

- Crucially, legal ownership (title) of the Vehicle would first transfer from the dealer to Y Finance. Y Finance would then "retain" this ownership as security until A had fully paid off the Retained Ownership Debt.

- A would take delivery of the Vehicle from the dealer and was responsible for managing it with the due care of a good manager.

- The agreement stipulated that if A defaulted on installment payments and failed to rectify the default after receiving notice from Y Finance, A would lose the "benefit of time" (kigen no rieki sōshitsu) for the remaining installments. This meant the entire outstanding balance of the Retained Ownership Debt would become immediately due and payable.

- In the event of such an acceleration of the debt, A agreed to consent without objection to Y Finance's demand for the return (delivery) of the Vehicle, based on Y Finance's retained ownership.

- If Y Finance repossessed the Vehicle from A, it was entitled to sell it at a fair appraised value and apply the sale proceeds to the outstanding Retained Ownership Debt.

- Under this agreement:

- Defaults: A subsequently defaulted on the installment payments owed to Y Finance and remained in default throughout the lower court proceedings. A also stopped paying rent to X for the parking space (the Land) from December 2004 onwards.

- Lease Termination and Continued Trespass: In April 2006, X validly terminated the Lease Agreement with A due to non-payment of rent. However, despite the lease termination, the Vehicle (legally owned by Y Finance, used by A) remained parked on X's Land, constituting a trespass.

- X's Lawsuit against Y Finance: X sued Y Finance, as the retained title holder of the Vehicle. X demanded that Y Finance (a) remove the Vehicle from the Land, (b) ensure vacant possession of the Land, and (c) pay damages equivalent to the fair usage fee for the Land for the period of unauthorized occupation. (X had also sued A, the user, and had already obtained a default judgment against A for similar claims).

Lower Courts: Finance Company Not Responsible

Both the District Court and the High Court dismissed X's claims against Y Finance. The High Court, for instance, reasoned that Y Finance's retained ownership was "in substance merely a security interest" and not "normal legal ownership which includes the power of use and possession." It concluded that even if A had defaulted and lost the benefit of time on the loan, Y Finance did not automatically incur an obligation to repossess and store the Vehicle, and therefore could not be held responsible for its removal from X's land. X, dissatisfied with this outcome, sought and was granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (March 10, 2009): A Two-Tiered Responsibility

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings, establishing a critical distinction in the retained title holder's liability based on whether the underlying debt had been fully accelerated.

I. Understanding Y Finance's Retained Ownership Rights:

The Court first analyzed the nature of Y Finance's rights under the financing agreement:

- Y Finance acquired ownership of the Vehicle as security for A's repayment of the advanced purchase price.

- As long as A did not lose the "benefit of time" (i.e., was not in such default as to make the entire debt immediately due), Y Finance had no right to possess or use the Vehicle itself.

- However, once A did lose the benefit of time and the entire remaining debt became due and payable, Y Finance acquired the right to take delivery of the Vehicle from A, sell it, and apply the proceeds to satisfy the outstanding debt.

II. Retained Title Holder's Obligations Regarding a Vehicle Trespassing on Third-Party Land:

Based on this understanding of the finance company's evolving rights, the Supreme Court laid down the following general principles for a retained title holder's responsibility when the financed movable (the Vehicle) is infringing upon a third party's land ownership rights:

- Responsibility Before Full Debt Acceleration (Loss of Benefit of Time):

"The retained title holder, until the arrival of the due date for the entire remaining debt following a loss of the benefit of time (hereinafter 'due date of remaining debt'), even if the said movable exists on a third party's land and obstructs the third party's exercise of land ownership, shall, absent special circumstances, generally not bear an obligation to remove the said movable or tort liability."- Rationale: At this stage, the retained title holder's right is primarily to "grasp the exchange value of the said movable" as security. They do not yet have the direct power to possess or dispose of the movable, as those rights are still effectively with the buyer.

- Responsibility After Full Debt Acceleration:

"However, after the due date of the remaining debt has passed, it is reasonable to construe that the retained title holder cannot escape the aforementioned removal obligation or tort liability merely because the retained ownership has the nature of a security interest."- Rationale: "This is because the retained ownership held by such a retained title holder, while in principle limited to grasping the exchange value of the said movable until the arrival of the due date of the remaining debt, is construed as conferring the power to possess and dispose of the said movable after the due date of the remaining debt has passed."

III. Tort Liability (Damages) – Additional Condition of Knowledge:

The Supreme Court added a specific condition for imposing tort liability (i.e., the obligation to pay monetary damages for the unlawful occupation) on the retained title holder, even after debt acceleration:

"However, even after the due date of the remaining debt has passed, it is reasonable to construe that the retained title holder, as a general rule, will not be questioned for tort liability unless they knew of the fact that the said movable was obstructing the third party's exercise of land ownership, and will bear tort liability when they become aware of this fact, such as by being informed of the said obstruction."

Reason for Remand:

The Supreme Court found that the lower courts had dismissed X's claims without adequately determining a crucial factual predicate: whether A's entire Retained Ownership Debt to Y Finance had actually become due (i.e., whether A had lost the benefit of time and the debt had been properly accelerated). Under Japanese law, particularly the Installment Sales Act which applies to such consumer credit arrangements, specific procedures (such as a written demand for payment within a reasonable period of at least 20 days) are typically required to accelerate the debt. Since the lower courts had only found that A was continually in arrears with installments, but not that the entire debt had become due after proper procedures, the Supreme Court remanded the case for this point to be properly investigated and determined so that the two-tiered liability principles it had just established could be correctly applied. (The case was reportedly settled by agreement after remand).

Understanding Retained Ownership as a Security Device

Retained ownership or title retention is a common security device in installment sales. While the seller (or, as here, the finance company that pays the seller on the buyer's behalf) formally retains "ownership" of the goods until the buyer pays the full price, this ownership is primarily for security purposes.

- Economically, it functions much like a chattel mortgage or a security interest under other legal systems. The buyer has the right to possess and use the goods, while the seller/financier holds title as leverage to ensure payment and as a basis for repossession and sale upon default.

- This Supreme Court judgment effectively acknowledges the hybrid nature of retained ownership. While formally "ownership," its practical exercise and the responsibilities attaching to it evolve. The Court's approach here is analogous to how it has treated another non-statutory Japanese security device, the "security transfer" (jōto tanpo), where the powers of the secured party (who also holds formal title) expand significantly upon the debtor's default and the acceleration of the debt.

The Significance of "Loan Acceleration" (Loss of Benefit of Time)

The judgment places great emphasis on the moment the buyer's entire remaining debt becomes due (often referred to as "loan acceleration" or the "loss of the benefit of time" - kigen no rieki sōshitsu). This is the crucial turning point for determining the retained title holder's potential liability to the landowner:

- Before Acceleration: The finance company's rights are largely dormant concerning possession and disposal. The buyer is the one with primary control. Thus, the finance company is generally not responsible for where the buyer parks the vehicle.

- After Acceleration: The finance company gains active rights to repossess and sell the vehicle. This newfound power to control the vehicle's location and status is what triggers its potential responsibility to the landowner whose property is being trespassed upon. The duty to remove the offending item arises from the ability to control and remove it.

Landowner's Remedies and Practical Steps

This judgment provides a clearer path for landowners like X to seek remedies against finance companies in such situations, but it's not unconditional:

- Verify Debt Acceleration: The landowner must effectively ascertain or prompt a situation where the buyer's loan from the finance company is fully accelerated. Without this, the finance company is unlikely to be held responsible for removal.

- Notify the Finance Company: To lay the groundwork for a potential tort claim for damages (for the period of unlawful occupation after acceleration), the landowner should formally notify the finance company that the vehicle is trespassing on their property. This establishes the "knowledge" element required by the Supreme Court for tort liability to attach to the finance company.

The judgment does not absolve the actual user of the vehicle (A, in this case) from their own primary liability for trespass and any associated damages or removal obligations. The landowner can, and typically would, pursue the user directly. The significance of this ruling is that it provides an additional, albeit conditional, avenue against the finance company.

Comparison with Other Legal Concepts

- Chattel Mortgages: The commentary suggests that a holder of a standard chattel mortgage (which is a non-possessory security interest that does not involve title transfer to the mortgagee) might not have the same removal duty because they typically lack the direct power of possession and disposal that a retained title holder or a security transferee gains upon default and acceleration.

- "Nominal Owner" Liability: In some cases involving real property, Japanese courts have held persons who are merely "nominal owners" on the register liable for issues arising from the property (e.g., the M47 case: Supreme Court, February 8, 1994, Minshū Vol. 48, No. 2, p. 373). While there are parallels (Y Finance is the registered owner of the vehicle), the Supreme Court here based its reasoning on the substantive powers Y Finance acquired post-acceleration, rather than solely on its status as a formal titleholder from the beginning. The Court did not explicitly rely on the M47 "nominal owner" framework for its decision regarding the removal duty.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of March 10, 2009, provides a vital and pragmatic framework for allocating responsibility when a vehicle financed through a title retention agreement is abandoned on a third party's property. It establishes a clear demarcation: prior to the full acceleration of the buyer's loan, the finance company (retained title holder) generally bears no responsibility to the landowner for the vehicle's removal or for damages caused by its trespass. However, once the loan is accelerated (due to the buyer's default and proper notice procedures), the finance company, now having acquired the power to possess and dispose of the vehicle, also acquires a corresponding duty to the landowner to remove the trespassing vehicle. Furthermore, if the finance company knows of the ongoing trespass after loan acceleration, it may also face tort liability for continued unlawful occupation. This ruling carefully balances the security nature of retained title with the property rights of innocent third-party landowners, pegging the finance company's responsibility to its actual ability to control the offending asset.