Resume Lies and Workplace Truths: Japan's Supreme Court on Dismissal for Falsified Background (September 19, 1991)

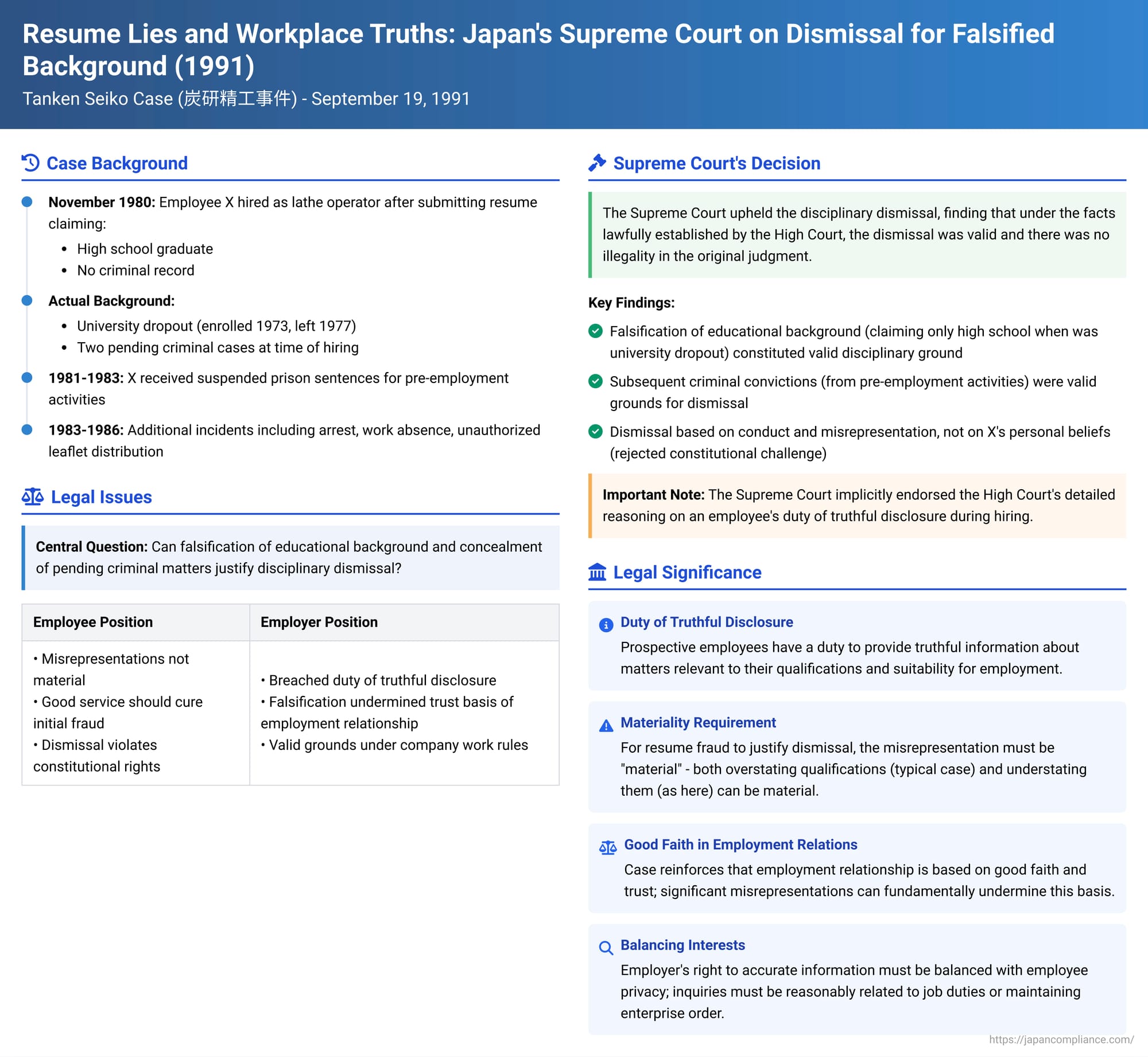

On September 19, 1991, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a significant case concerning an employee's dismissal for resume fraud (経歴詐称 - keireki sashō). This case, commonly known as the "Tanken Seiko Case" (炭研精工事件), affirmed the validity of a disciplinary dismissal based on an employee's misrepresentation of educational background and subsequent criminal convictions. It also implicitly supported the lower court's reasoning regarding an employee's duty of truthful disclosure during the hiring process, a point of considerable importance in Japanese labor law.

The Employee's Application and Concealed Past

In November 1980, Plaintiff X applied for a position as a lathe operator (among other roles) with Defendant Company Y, a precision engineering firm. The job vacancy, advertised through the Public Employment Security Office, was specifically targeted at individuals with either a middle school or high school education.

During the hiring process, X submitted a resume which stated:

- Educational background: High School Graduate.

- Criminal record: "None" (賞罰なし - shōbatsu nashi).

Based on this application and an interview, X was hired by Company Y on November 10, 1980.

However, X's actual background differed significantly from what was presented:

- True Educational Background: X had, in fact, enrolled in F University in 1973 and was subsequently disenrolled or withdrew from the university in 1977 without graduating. X was not merely a high school graduate.

- Pending Criminal Matters: At the precise time of the job interview and hiring by Company Y, X had two criminal cases pending against him. These cases stemmed from X's participation in protest activities related to the construction of Narita Airport. X was later convicted in both these cases, receiving suspended prison sentences from the Chiba District Court in January 1981 and June 1983, respectively, after joining Company Y.

Post-Hiring Incidents and Company Investigation

Several years into X's employment, other incidents occurred:

- In March 1983, X was arrested for violating the Minor Offenses Act due to distributing leaflets and was consequently absent from work.

- In March 1986, X was again arrested and detained, this time for allegedly obstructing the performance of public duties (though X was later not prosecuted for this). This led to a nine-day absence from work. During this period, a lawyer acting for X submitted a leave request to Company Y, citing the arrest as the reason. Company Y responded by sending X a registered letter stating that it did not recognize the arrest as a valid reason for absence. Upon returning to work, X distributed leaflets to other employees within Company Y's premises, without company permission, explaining the circumstances of the arrest.

Subsequently, Company Y conducted a more thorough investigation into X's background. This investigation revealed:

- The concealment of X's true educational background (university dropout instead of the claimed high school graduation).

- The concealment of the fact that two criminal trials were pending against X at the time of the employment interview.

- Allegations regarding the submission of false absence notifications (though this point was less central to the Supreme Court's final considerations).

Based on these findings, coupled with the 1986 nine-day absence and the unauthorized leaflet distribution, Company Y decided to disciplinarily dismiss X. During the ensuing legal proceedings, Company Y also cited the two criminal convictions (from 1981 and 1983, for the pre-employment protest activities) as additional grounds justifying the dismissal.

The Lower Courts: Upholding the Dismissal

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance): The District Court found the disciplinary dismissal to be valid. It upheld grounds (1) (educational background fraud), (2) (concealment of pending criminal trials at hiring), and (6) (the subsequent criminal convictions) as justifying the dismissal.

- Tokyo High Court (Appeal): The High Court also affirmed the validity of the disciplinary dismissal, primarily relying on ground (1) (educational background fraud) and ground (6) (the criminal convictions that occurred after X joined the company).

- On Educational Fraud: The High Court elaborated on the employee's duty of truthful disclosure. It reasoned that because the employment relationship is a continuous contractual one founded on mutual trust, an employer is entitled to request information from a prospective employee that is necessary and reasonable for evaluating not only their direct labor capabilities but also their suitability for the company culture, their willingness to contribute, and aspects relevant to maintaining the company's credit and internal order. The High Court deemed an applicant's final educational background to be a matter relevant not just to assessing their skills but also to the maintenance of Company Y's enterprise order. Therefore, it concluded that X had a good faith obligation to disclose this information truthfully, and the failure to do so constituted "being hired by falsifying personal history," a valid ground for disciplinary dismissal under Company Y's work rules.

- On Concealing Pending Trials: Interestingly, the High Court found that X's statement of "no criminal record/punishments" on the resume was not a falsehood at the time of the interview, because no convictions had been rendered in the pending cases at that point. Thus, this specific concealment did not, in itself, constitute a disciplinary ground for falsifying a criminal record. (However, as noted, the High Court did consider the subsequent convictions resulting from these pre-employment activities as valid grounds for dismissal).

Plaintiff X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's judgment that the disciplinary dismissal was valid.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise. It stated: "Under the facts lawfully established by the High Court, its judgment upholding the dismissal in this case as valid can be affirmed as correct, and there is no illegality in the original judgment as asserted in the arguments."

The Supreme Court specifically acknowledged that the High Court had found that X (i) having received two suspended prison sentences and (ii) having falsified educational background at the time of hiring, constituted grounds for disciplinary dismissal under Company Y's work rules. The High Court had then considered X's other conduct as part of the overall context in determining that the dismissal did not constitute an abuse of the employer's right to dismiss.

The Supreme Court also briefly addressed and rejected X's constitutional arguments (e.g., violation of Article 19 – freedom of thought and conscience), stating that the dismissal was based on the established disciplinary grounds related to conduct and misrepresentation, not on X's personal beliefs.

Deeper Dive: The Duty of Truthful Disclosure and "Materiality"

Although the Supreme Court's own reasoning was brief, its affirmation of the High Court's judgment, which included detailed reasoning on the employee's duty of disclosure, carries significant weight.

- Employee's Duty of Truthful Disclosure: The case implicitly endorses the principle that prospective employees have a duty, rooted in good faith, to provide truthful information when an employer makes reasonable and necessary inquiries during the hiring process. This duty extends not only to matters directly assessing skills and qualifications but also to information relevant to the employee's potential adaptability, motivation, and the overall maintenance of "enterprise order."

- The commentary notes that while this general principle is accepted, especially for information that could affect the viability of the employment contract, invoking abstract concepts like "continuous contractual relationship" or "enterprise order" too broadly risks an almost limitless expansion of this disclosure duty. Some academic views argue for limiting this duty primarily to information directly pertinent to the actual performance of labor. It's also clear that this duty does not compel disclosure of information protected by anti-discrimination laws (e.g., LSA Article 3 concerning creed or social status).

- The obligation to disclose is generally triggered by employer inquiry. There isn't necessarily a proactive duty to volunteer all potentially negative information if not asked, especially if it's highly likely to prevent hiring.

- Resume Fraud as Grounds for Disciplinary Dismissal: The case affirms that significant misrepresentations in the hiring process can indeed constitute valid grounds for disciplinary dismissal under work rules.

- The commentary discusses various academic theories on why pre-employment conduct (like resume fraud) can justify post-employment discipline. The "abstract danger theory," suggesting that a significant misrepresentation inherently breaches the good faith basis of the employment relationship and thus enterprise order, aligns with the reasoning implicitly supported in this case.

- The Crucial Element of "Materiality": For resume fraud to justify dismissal, the misrepresentation must be "material" or "important" (重要なもの - jūyō na mono). Not every inaccuracy will suffice.

- Educational Background: Falsifying educational attainment is often treated as material, whether by overstating qualifications or, as in this case, by understating them (e.g., a university dropout claiming only high school graduation to fit a specific job profile). Courts tend to uphold dismissals in such cases because educational background can significantly influence an employer's assessment of an individual's capabilities, suitability for particular roles, expected career progression, and pay scales, as well as internal equity with other employees. However, if an employer demonstrably places little to no emphasis on educational qualifications during hiring for a particular role, then a misstatement might not be deemed "material."

- Criminal Record: Concealing a criminal record can also be a material misrepresentation justifying dismissal, especially for convictions relevant to the nature of the work or trustworthiness. However, the High Court in this case specifically noted that pending criminal trials where no judgment has yet been delivered do not make a statement of "no prior convictions" false at that moment. The subsequent convictions, however, were considered valid grounds. The commentary also mentions that after a sentence is legally "extinguished" (刑の消滅 - kei no shōmetsu under Penal Code Article 34-2), there may no longer be a duty to disclose that past conviction. Minor offenses unrelated to job duties are also less likely to be considered material.

- Can Long-Term Good Service "Cure" Resume Fraud? Some scholars argue that if an employee performs well for an extended period after being hired based on a misrepresentation, the initial breach of good faith might be considered "healed" or outweighed by subsequent good service. However, Japanese case law has generally been hesitant to accept this argument.

- Employer's Right to Investigate vs. Employee Privacy: The commentary raises an important related point: the employee's duty of truthful disclosure must be viewed in conjunction with the permissible scope of an employer's pre-employment investigations and respect for employee privacy. While an earlier Supreme Court case (the Mitsubishi Jushi Case) took a broad view of the employer's freedom to investigate, subsequent legal developments and societal norms around data protection and privacy have imposed greater restrictions. Modern guidelines, for example, restrict employers from collecting personal information that could lead to social discrimination or that pertains to an individual's thoughts or beliefs, and limit the acquisition of health information without consent. The commentary suggests that if an employer's inquiries delve into highly private matters that are irrelevant to job duties or capabilities, the inquiries themselves might be unlawful, meaning no duty of truthful disclosure would arise for the employee regarding those matters.

Conclusion: The Weight of Truth in Employment

The Supreme Court's decision in the Precision Engineering Company Y (Tanken Seiko) case reaffirms the significant consequences of resume fraud in Japanese employment law. By upholding the disciplinary dismissal of an employee who misrepresented his educational background and had subsequent criminal convictions (stemming from pre-employment activities), the Court underscored the importance of truthfulness and good faith in the hiring process. The case implicitly supports the principle that employers are entitled to make hiring decisions based on accurate information, particularly concerning qualifications and factors relevant to enterprise order. While not every misstatement will justify dismissal, material falsifications that could have influenced the hiring decision or impact the employment relationship can provide valid grounds for severe disciplinary action, including termination. The ruling also subtly highlights the evolving balance between an employer's need for relevant information and an employee's right to privacy, suggesting that the scope of an employee's disclosure duty is linked to the reasonableness and relevance of the employer's inquiries.