Restricted Shares, Unapproved Transfers: Valid Between Parties, Not Against the Company – A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: June 15, 1973

Case: Action for Declaratory Judgment of Invalidity of Share Transfer Security Agreement (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

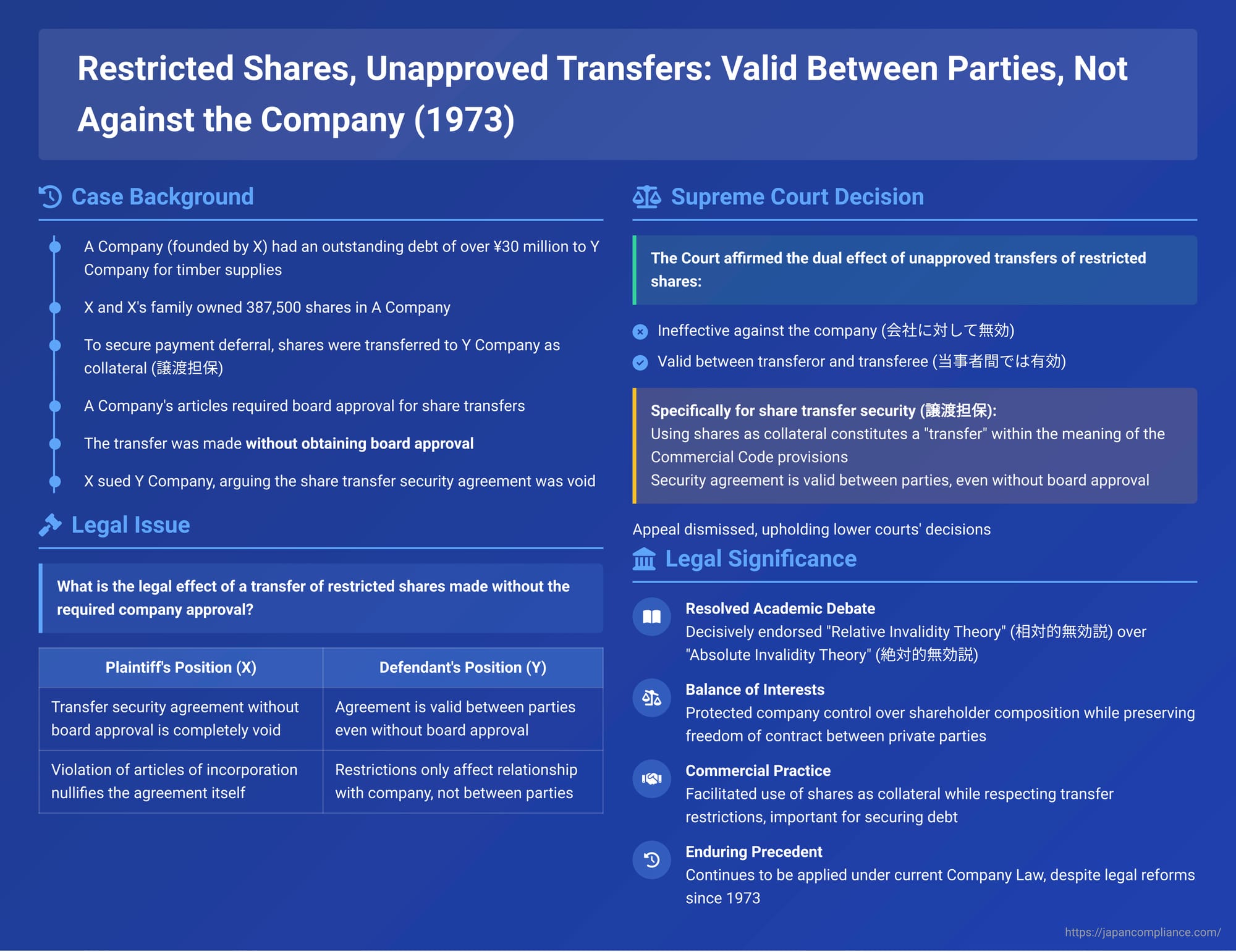

This landmark 1973 decision by the Japanese Supreme Court addressed a fundamental question concerning shares with transfer restrictions: What is the legal effect of a transfer of such shares made without the required company approval, particularly when the transfer is for the purpose of providing security (譲渡担保 - joto tanpo)? The Court drew a crucial distinction between the validity of the transfer as between the immediate parties and its enforceability against the company.

Factual Background: A Debt, Collateral, and Unapproved Share Transfer

The case involved A Company, a plywood and veneer manufacturer founded by X. X and their family (X2 et al.) collectively owned 387,500 shares in A Company ("the shares").

A Company had an outstanding debt of over JPY 30 million to Y Company for timber supplies. To secure a deferral on this payment, an agreement was made to provide the shares to Y Company as collateral. Consequently, share certificates representing these shares were delivered to Y Company.

A Company's articles of incorporation included a provision requiring the approval of its board of directors for any transfer of its shares. However, the transfer of the shares to Y Company as security was made without obtaining this board approval.

X and X2 et al. (the original shareholders) filed a lawsuit, arguing that the share transfer security agreement was void due to the lack of board approval. Both the court of first instance and the High Court dismissed their claim. These lower courts held that while a transfer security agreement lacking board approval was indeed ineffective against A Company, it remained valid and binding as between the parties involved (i.e., X et al. as transferors and Y Company as transferee). Dissatisfied, X et al. appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: A Dual Standard of Validity

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions. The Court's reasoning was delivered in two key parts:

Part I: General Principle for Transfers of Restricted Shares

The Court acknowledged that the Commercial Code then in effect (Article 204(1), proviso) permitted companies to include provisions in their articles of incorporation requiring board of directors' approval for share transfers. The legislative purpose behind allowing such restrictions, the Court explained, was primarily to prevent individuals undesirable to the company from becoming shareholders.

Considering this specific legislative intent, alongside the fundamental principle that shares should ordinarily be freely transferable, the Court concluded that a transfer of shares made without the requisite board approval (where such a restriction exists in the articles) has the following effect:

- It is ineffective against the company.

- However, it is valid as between the transferor and the transferee.

Part II: Application to Share Transfers for Security (Joto Tanpo)

The Court then specifically addressed the nature of providing shares as security via joto tanpo.

- It held that using shares as joto tanpo (a form of security where title is formally transferred to the creditor, to be returned upon debt repayment) constitutes a "transfer" of shares within the meaning of the Commercial Code's provisions on share transfers.

- Therefore, the general principle outlined in Part I applies directly. Even if board approval is not obtained for providing transfer-restricted shares as joto tanpo, the security agreement is valid between the parties involved, and the rights associated with the shares are effectively transferred from the transferor to the transferee as far as their mutual relationship is concerned.

Analysis and Implications: Navigating Share Transfer Restrictions

This 1973 Supreme Court judgment remains a cornerstone in understanding the legal landscape of transfer-restricted shares in Japan.

1. The Evolution of Share Transfer Restrictions in Japan

The free transferability of shares is a foundational principle in company law (current Company Law, Article 127). This is because, unlike members of certain types of partnerships, shareholders in a stock company (kabushiki kaisha) typically cannot demand a return of their capital contribution from the company itself; selling their shares is often the primary way to recoup their investment.

- Historical Context: Before 1950, the Japanese Commercial Code allowed for share transfer restrictions in a company's articles. A 1950 revision briefly made free transferability an absolute rule, disallowing all such restrictions.

- Reintroduction of Restrictions (1966): The 1966 revision to the Commercial Code reintroduced the ability for companies to restrict share transfers by requiring board of directors' approval (former Commercial Code, Article 204(1), proviso). This change was partly motivated by concerns over foreign takeovers following capital liberalization, but also responded to the needs of the many small and medium-sized closely-held companies in Japan that wished to maintain control over their shareholder composition, preferring shareholders with whom they had personal trust. To safeguard shareholders' ability to exit, this revision also mandated that if a company refused to approve a transfer, it had to designate an alternative purchaser.

- Current Company Law (Post-2005): The current Company Law has further refined and expanded these provisions. Companies can make all their shares subject to transfer restrictions (Company Law, Article 107(2)(i)) or issue specific classes of shares that require company approval for transfer (Article 108(2)(iv)). The approval process itself has become more flexible:

- The acquirer, not just the transferor, can request the company's approval (Article 137(1), 138(2)).

- The approving body is the board of directors for companies with a board, and the shareholders' meeting for others, unless the articles specify otherwise (Article 139).

- Articles can also specify circumstances where approval is not needed (Article 107(2)(i)(b), 108(2)(iv)) or pre-designate an alternative buyer if approval is denied (Article 140(5), proviso).

- Additionally, the Company Law allows companies to include provisions in their articles enabling them to require heirs or other successors who acquire transfer-restricted shares through general succession (e.g., inheritance, merger) to sell those shares back to the company or its designee, thus providing a mechanism to exclude unintended successors (Articles 174-177).

2. The Validity of Unapproved Transfers: A Longstanding Debate Resolved

Before this 1973 Supreme Court decision, legal scholarship in Japan was divided on the effect of a transfer of restricted shares made without board approval.

- Absolute Invalidity Theory (Zettai Setsu): One view held that if the transfer was ineffective against the company, it should also be considered void as a quasi-property transaction even between the transferor and transferee. Proponents argued this was a natural interpretation and that allowing inter-party validity could undermine the purpose of the restriction, for instance, by allowing the unapproved transferee to instruct the registered transferor on how to vote the shares.

- Relative Invalidity Theory (Sotai Setsu): The opposing view, which was the majority opinion among scholars, contended that the transfer, while ineffective against the company, should be considered valid between the immediate parties. The reasoning was that the objective of the transfer restriction—to prevent undesirable persons from becoming active shareholders—was sufficiently achieved by denying the unapproved transferee the ability to exercise shareholder rights against the company. There was no need to invalidate the transaction between the parties themselves. Furthermore, certain provisions in the former Commercial Code (like Article 204-2, which allowed an acquirer of restricted shares via public auction to request company approval) seemed to presume that a valid transfer between the parties had already occurred, pending company approval.

The 1973 Supreme Court judgment decisively endorsed the Relative Invalidity Theory. This means the transfer creates a valid contractual obligation and transfer of beneficial interest between the seller and the buyer, even though the buyer cannot yet assert shareholder rights (like voting or receiving dividends directly) against the company until approval is obtained or the company otherwise recognizes the transfer (e.g., by registering the name change).

Subsequent Supreme Court case law (e.g., a decision on March 15, 1988) has reaffirmed this stance, explicitly stating that if approval for a transfer of restricted shares is lacking, the company is obligated to continue treating the transferor (the seller still on the register) as the shareholder. Lower courts operating under the current Company Law have also followed this established precedent.

Interestingly, drafters of the current Company Law have commented that, in their understanding, even under the prior Commercial Code, the validity of the transfer itself (between parties) was generally accepted, with the restrictions primarily affecting the registration of the new shareholder in the company's shareholder register. This commentary has been interpreted by some to suggest a leaning towards the transfer being effective even against the company to a certain degree, explaining, for instance, why an acquirer has the right to request approval from the company under Article 137 of the Company Law—because they are, in some sense, already considered a shareholder vis-à-vis the shares acquired. However, the majority of legal scholars today maintain that the traditional "Relative Invalidity" doctrine as confirmed by the 1973 Supreme Court ruling continues to be the prevailing interpretation under the current Company Law.

3. Transfer-Restricted Shares Used as Security (Joto Tanpo)

The second part of the 1973 Supreme Court judgment specifically clarified that providing transfer-restricted shares as joto tanpo is indeed a "transfer" for the purposes of these restrictions. Therefore, setting up such a security interest also formally requires board approval if the shares are restricted, and the restrictions on transfer apply to the registration of this security transfer on the shareholder register.

However, this aspect has generated further academic discussion:

- Approval Timing: Some scholars argue that company approval should not be necessary merely for the creation of a security interest in restricted shares. Instead, approval should only become relevant when the secured party seeks to enforce that security interest (e.g., by selling the shares to a third party or taking them over).

- "Informal" Security Transfers (Ryakushiki Joto Tanpo): For companies that issue share certificates, an "informal" security transfer can occur where the share certificates are delivered to the creditor, but no change is made to the shareholder register. In such cases, the secured creditor typically does not intend to exercise shareholder rights against the company until enforcement becomes necessary. Given the Supreme Court's ruling that the security arrangement is valid between the parties even without company approval, the secured creditor is protected against the debtor and the debtor's other general creditors, so the lack of company approval at the creation stage might not pose a significant practical problem for the creditor.

- Non-Share Certificate Companies (Excluding Book-Entry): For shares of companies that do not issue certificates (and are not on the book-entry system), entry in the shareholder register is the means by which a transfer (including a transfer for security, if registered) is perfected against the company and other third parties (Company Law, Article 130(1)). If the 1973 Supreme Court's ruling is strictly applied to such "registered security transfers" (toroku joto tanpo), a potential issue arises: if the debtor repays the debt and seeks the return of the shares, this "return" transfer might also require fresh company approval. If approval is denied at that stage, the debtor could face difficulties in recovering full, unrestricted title. Some argue, however, that if the initial security transfer was approved, the debtor's re-acquisition upon repayment is simply a new acquisition from the company's perspective and thus naturally requires its own approval.

Conclusion: A Lasting Principle with Ongoing Debate

The Supreme Court's 1973 decision established a clear and enduring principle: a transfer of restricted shares made without the required company board approval is valid and effective between the transferor and transferee, though it cannot be asserted against the company until approval is obtained. This principle also extends to transfers for security purposes, such as joto tanpo. While providing much-needed clarity, the ruling, especially concerning security transfers in the context of modern non-share certificate companies, continues to be a subject of academic discussion regarding its nuanced application and potential for creating complexities in certain scenarios. Nonetheless, it remains a foundational judgment for understanding the interplay between contractual freedom, corporate control over shareholder identity, and the nature of share ownership in Japan.