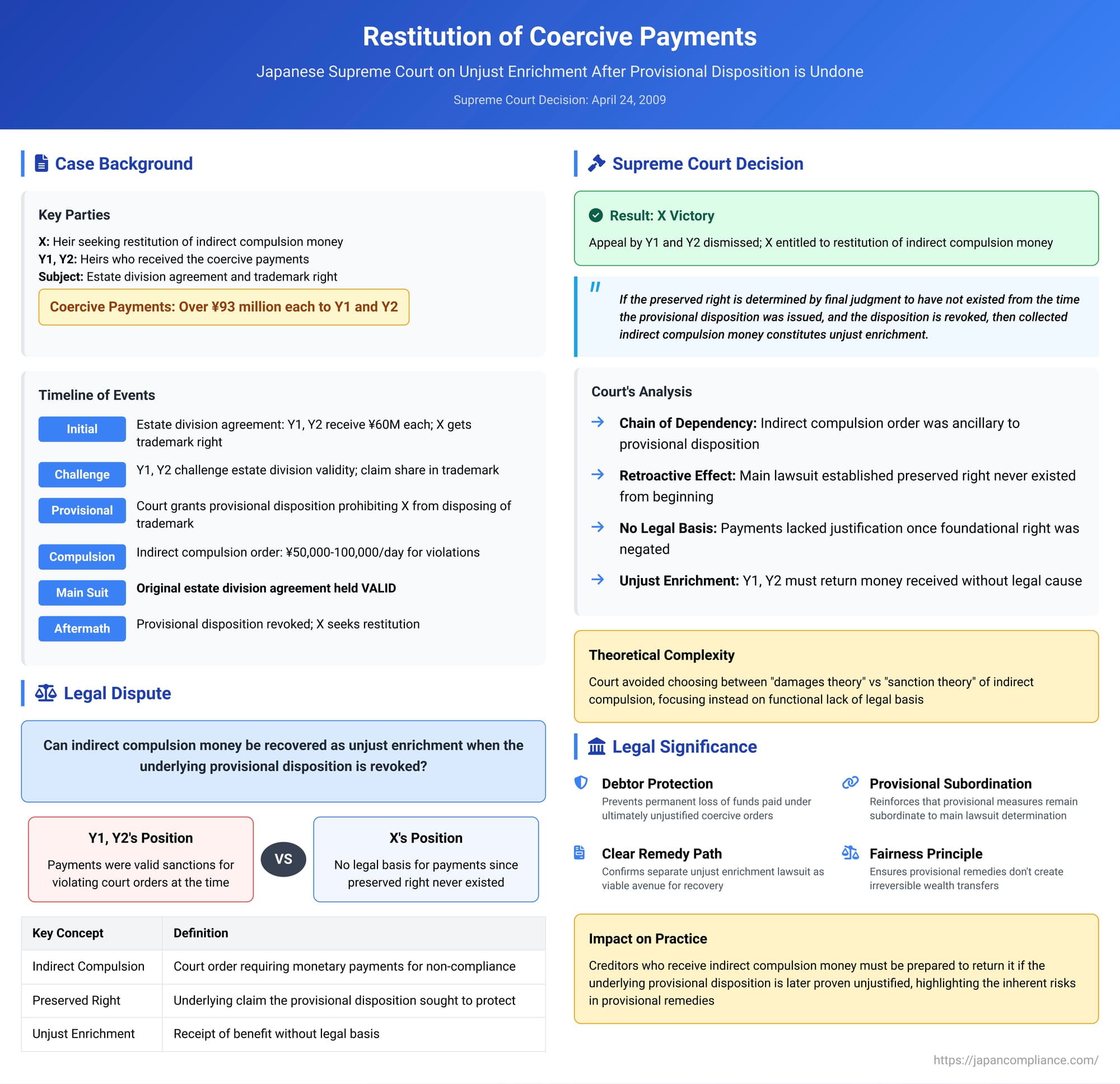

Restitution of Coercive Payments: Japanese Supreme Court on Unjust Enrichment After Provisional Disposition is Undone by Main Lawsuit

Date of Supreme Court Decision: April 24, 2009

In Japanese civil procedure, provisional dispositions (仮処分 - karishobun) serve as interim measures to protect a claimant's rights pending a final judgment. To ensure compliance with certain types of provisional dispositions, particularly those ordering or prohibiting specific actions, courts can issue "indirect compulsion" orders (間接強制決定 - kansetsu kyōsei kettei). These orders require the non-compliant party (the debtor) to pay a certain amount of money (間接強制金 - kansetsu kyōseikin, or indirect compulsion money) for each day or instance of violation, thereby creating strong financial pressure to comply. A critical question arises when the underlying provisional disposition is later found to have been unjustified—specifically, if the main lawsuit determines that the right the provisional disposition sought to protect never actually existed, and the provisional disposition is subsequently revoked. Can the debtor then recover the indirect compulsion money they paid? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this precise issue in its decision of April 24, 2009 (Heisei 20 (Ju) No. 224).

The Factual Saga: An Estate Dispute, a Provisional Ban, and Coercive Payments

The case originated from a dispute among the heirs of the deceased A: X (the plaintiff in the restitution claim) and Y1 and Y2 (the defendants in the restitution claim).

- Estate Division and Initial Dispute: An estate division agreement was initially concluded, under which Y1 and Y2 were each to inherit ¥60 million, with the remainder of the estate, including a valuable trademark right ("Honken Shōhyōken"), going to X. Subsequently, Y1 and Y2 challenged the validity of this estate division agreement.

- Provisional Disposition and Indirect Compulsion:

- Provisional Disposition: Assuming the original estate division agreement was invalid, Y1 and Y2 claimed a share in the trademark right based on their statutory reserved portion of the estate (遺留分減殺請求権 - iryūbun gensai seikyūken). On this basis (this asserted share being their "preserved right" – 被保全権利 - hihozen kenri), they applied for and obtained a provisional disposition from the court. This order prohibited X from disposing of the trademark right.

- Indirect Compulsion: X allegedly failed to comply with this disposition prohibition. Consequently, Y1 and Y2 applied for and obtained an indirect compulsion order against X. This order mandated X to pay Y1 and Y2 ¥50,000 each (an amount later increased to ¥100,000 each) per day for continued violation of the provisional disposition. Through the execution of this indirect compulsion order, Y1 and Y2 each collected over ¥93 million from X.

- Outcome of the Main Lawsuit: Parallel to these provisional measures, Y1 and Y2 had initiated a main lawsuit against X concerning the estate division (seeking transfer of title to land, buildings, etc., based on their claim that the original division was invalid). In this main lawsuit, the appellate court ultimately ruled that the original estate division agreement was, in fact, valid. This crucial finding meant that Y1 and Y2 never possessed the "preserved right" (the share in the trademark based on a reserved portion claim that would only arise if the division were invalid) that had formed the basis for their successful application for the provisional disposition. This judgment in the main lawsuit became final and binding.

- Revocation of Provisional Measures: Following this definitive outcome in the main lawsuit—which constituted a "change in circumstances" (事情変更 - jijō henkō) demonstrating that the provisional disposition had been granted on a false premise—X successfully applied for and obtained a court decision revoking the original provisional disposition. Subsequently, X also secured a revocation of the indirect compulsion order that had been based upon it.

- X's Lawsuit for Restitution: Having paid substantial sums under the now-revoked indirect compulsion order, X filed the present lawsuit against Y1 and Y2. X argued that the indirect compulsion money received by Y1 and Y2 constituted unjust enrichment (不当利得 - futō ritoku) and demanded its return.

The Fukuoka District Court (court of first instance in the restitution case) partially ruled in favor of X, holding that the revocation of the indirect compulsion order had retroactive effect, thus rendering the payments an unjust enrichment. The Fukuoka High Court also found for X, reasoning that since the main lawsuit established that the preserved right never existed from the outset, Y1 and Y2's retention of the indirect compulsion money lacked a just cause, irrespective of the retroactivity of the revocation orders. The High Court stated that the sanction itself (the indirect compulsion money) against X was devoid of a legitimate basis because the underlying obligation (not to dispose of the trademark) stemmed from a non-existent right.

Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Payments Based on a Nullified Premise are Unjust Enrichment

The Supreme Court, in its decision of April 24, 2009, dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby affirming X's right to recover the indirect compulsion money.

Core Holding: The Court held that if the right that a provisional disposition sought to preserve is determined by a final judgment in the main lawsuit to have not existed from the time the provisional disposition was issued, and the provisional disposition is subsequently revoked based on this "change in circumstances," then the debtor (who was subject to that provisional disposition) can claim restitution from the creditor for any money collected through an indirect compulsion order that was issued to enforce that provisional disposition. Such collected money constitutes unjust enrichment.

Deconstructing the Supreme Court's Reasoning:

- The Purpose of Indirect Compulsion: The Court began by defining indirect compulsion. It is a procedural mechanism designed to ensure a debtor's compliance with an obligation specified in an "enforceable title" (債務名義 - saimu meigi), such as a court judgment or, as in this case, a provisional disposition order. It works by imposing a monetary penalty for non-compliance.

- The Provisional Disposition as the Enforceable Title: In the context of enforcing provisional measures, the provisional disposition order itself serves as the enforceable title upon which an indirect compulsion order can be based. The indirect compulsion order is thus ancillary to, and dependent upon, the validity and enforceability of the underlying provisional disposition.

- Impact of the Main Lawsuit's Finding on the "Preserved Right": The critical turning point is the final judgment in the main lawsuit. If this judgment definitively establishes that the "preserved right" – the substantive claim that the provisional disposition was intended to protect – was non-existent from the very beginning (i.e., from the time the provisional disposition was issued), then the entire foundation of the provisional disposition is retroactively undermined.

- Indirect Compulsion Based on a Non-Existent Obligation: When the provisional disposition is subsequently revoked due to this finding (as a "change in circumstances" showing its initial lack of basis), it becomes clear that the indirect compulsion order, which was predicated on that provisional disposition, was effectively issued to ensure compliance with an obligation (in this case, X's obligation not to dispose of the trademark) that, in substantive legal reality, never existed in favor of Y1 and Y2.

- Lack of Legal Basis for the Payments: Therefore, the indirect compulsion money that was collected by the creditors (Y1 and Y2) from the debtor (X) based on this chain of subsequently nullified orders is deemed to lack a "legal basis" (法律上の原因 - hōritsujō no gen'in). Under Japanese law, the receipt of a benefit without a legal basis constitutes unjust enrichment, and the recipient is obliged to return that benefit.

Nature of Indirect Compulsion Money and Its Restitution

The Supreme Court's decision, while clear in its outcome, navigated complex theoretical waters regarding the nature of indirect compulsion money and the basis for its restitution.

- Provisional Dispositions vs. Final Judgments: Generally, if money is transferred based on a final and binding judgment, that transfer has a legal basis, and the money is not considered unjust enrichment even if the judgment might have been substantively incorrect (unless the judgment is later overturned through a formal retrial procedure, which can have retroactive effect). Provisional dispositions, however, are inherently temporary and do not create final substantive rights. Their revocation, especially when based on a finding in the main lawsuit that the underlying claim was invalid from the start, logically unravels the basis for any payments made under their coercive force. Legal commentary suggests that the revocation of a provisional disposition because the main case determined the preserved right never existed is generally considered to have retroactive effect.

- Restitution Mechanisms: The current Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA), in Article 33 (and Article 40), provides a streamlined procedure for claiming restitution of benefits received under a provisional disposition if that disposition is later revoked or altered within the same procedural framework. However, there's a debate whether indirect compulsion money falls directly under "money paid based on the provisional disposition order" for the purposes of Article 33, as it's paid under a separate indirect compulsion order, albeit one enforcing the provisional disposition. The Supreme Court's decision in this case affirms the viability of a separate plenary lawsuit for unjust enrichment to recover such funds, which is a crucial clarification.

- Theories on the Nature of Indirect Compulsion Money:

- Damages Theory: Historically, particularly under the old Code of Civil Procedure, indirect compulsion payments were often viewed as akin to damages for non-compliance with the primary obligation. If the underlying obligation (e.g., not to dispose of property) was based on a non-existent right, then no true "damage" from its "breach" could logically occur, making recovery straightforward.

- Sanction Theory (制裁説 - seisai-setsu): Under the current Civil Execution Act (Article 172), a strong view is that indirect compulsion money functions primarily as a "sanction" or "penalty" for disobeying the court's (indirect compulsion) order itself, aimed at compelling future compliance, rather than just compensating for past non-compliance. If viewed purely as a sanction for violating the indirect compulsion order (which was formally in effect at the time of violation), one might argue that the money should be retained by the creditor even if the underlying provisional disposition is later revoked, as the disobedience to the specific compulsion order did occur. This was a line of argument pursued by Y1 and Y2.

- Mixed Theories: Some theories view indirect compulsion money as having elements of both damages (compensating the creditor) and sanction (coercing the debtor).

- Supreme Court's Pragmatic Approach: The Supreme Court in this 2009 decision did not explicitly endorse one specific theory (damages, sanction, or mixed) regarding the intrinsic nature of indirect compulsion money. Instead, it focused on a more fundamental and pragmatic principle: indirect compulsion is a means to ensure performance of an obligation contained in an enforceable title. If the enforceable title (the provisional disposition) is subsequently shown to have been predicated on a substantive right that never existed, then the "means" (the indirect compulsion payments) lose their ultimate legal justification. This functional approach leads directly to the conclusion of unjust enrichment without needing to resolve the finer theoretical debates about the money's precise characterization, though its reasoning is highly compatible with views that see the indirect compulsion order as ancillary to and dependent on the validity of the primary provisional disposition.

Scope and Significance of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision is significant for several reasons:

- It provides clear authority that indirect compulsion payments made to enforce a provisional disposition must be returned as unjust enrichment if the main lawsuit ultimately determines that the right sought to be preserved by that provisional disposition was non-existent from its inception, leading to the revocation of the provisional disposition.

- It protects debtors from being permanently deprived of substantial sums paid under coercive orders that were later found to be fundamentally unjustified due to a lack of a valid underlying claim by the creditor.

- It reinforces the principle that provisional remedies and their enforcement mechanisms are ancillary and subordinate to the final determination of substantive rights in the main litigation. While provisional measures provide necessary interim protection, they do not create irreversible substantive entitlements if their initial basis is proven flawed.

- The ruling clarifies that a separate unjust enrichment lawsuit is an appropriate avenue for recovering such indirect compulsion payments, particularly given potential ambiguities about the direct applicability of the summary restitution provisions in CPRA Article 33 to monies paid under a distinct indirect compulsion order.

Concluding Thoughts

The April 24, 2009, Supreme Court decision is a critical judgment in the landscape of Japanese civil provisional remedies and execution law. It ensures that the powerful tool of indirect compulsion, when used to enforce a provisional disposition, does not lead to an irreversible and unjust transfer of wealth if the provisional disposition itself is ultimately proven to have been granted without a valid underlying substantive right. By focusing on the absence of a "legal basis" for the payments once the foundational preserved right is negated, the Court provides a clear path for the restitution of such coercive payments, thereby upholding principles of fairness and ensuring that provisional measures remain subordinate to the final adjudication of rights. This decision is vital for understanding the consequences of provisional orders being overturned and the remedies available to parties who have made payments under such orders.