Respecting Arbitration: Japanese Supreme Court on Governing Law and Effect of International Arbitration Agreements

Date of Judgment: September 4, 1997

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

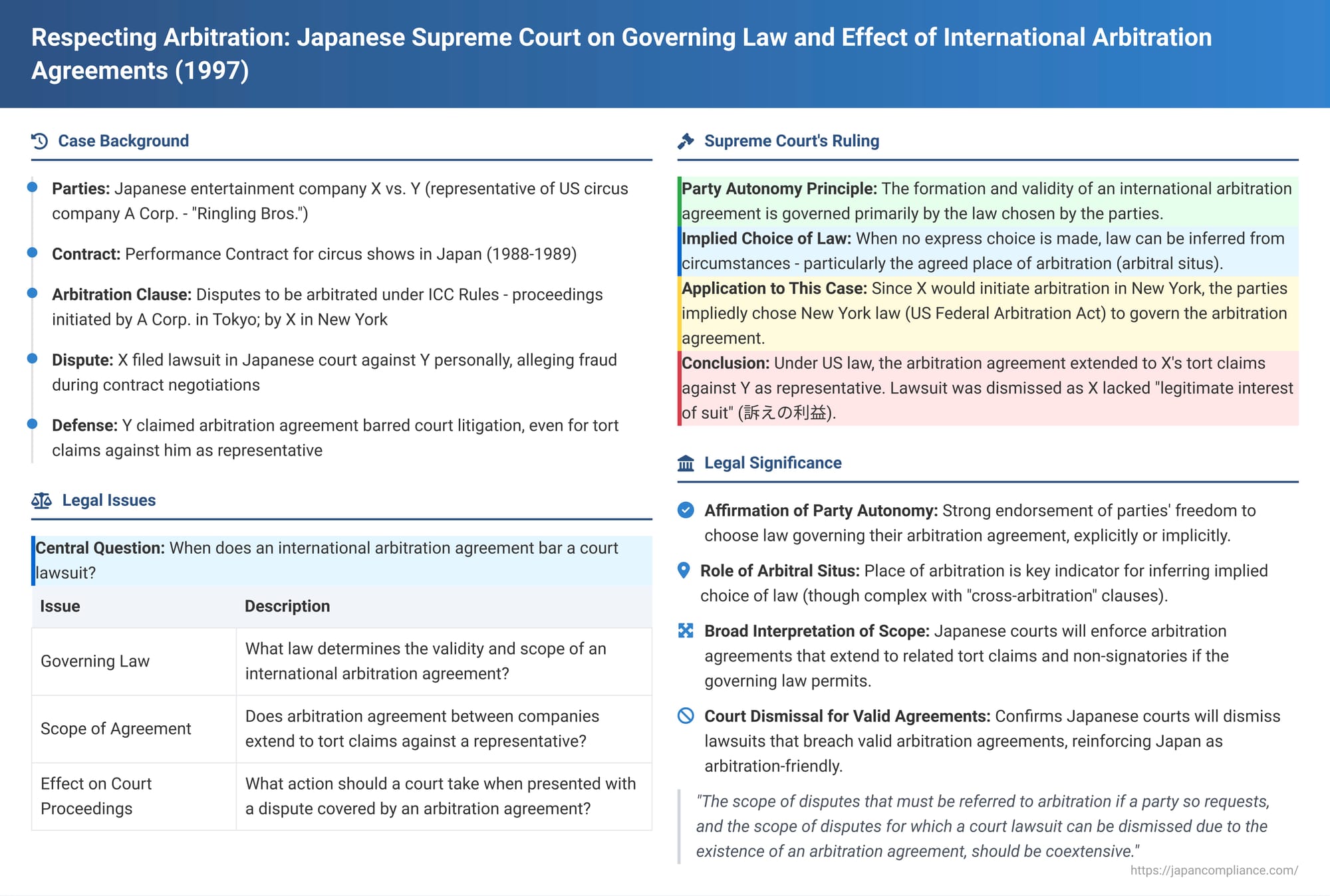

International commercial arbitration has become a preferred method for resolving cross-border business disputes, offering neutrality, expertise, and enforceability through treaties like the New York Convention. A cornerstone of this system is the arbitration agreement, by which parties commit to arbitrate rather than litigate in national courts. A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on September 4, 1997, often referred to in connection with the "Ringling Bros." circus, provided crucial clarifications on how Japanese courts determine the law governing such international arbitration agreements and their effect when a party nonetheless attempts to sue in court.

The Factual Background: A Circus Deal and a Demand for Court Litigation

The case involved a dispute arising from a contract to bring a U.S. circus to Japan:

- X (Plaintiff): A Japanese corporation engaged in producing educational events and general entertainment.

- A Corp.: A U.S. corporation operating circus performances (specifically, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows, Inc.).

- Y (Defendant): The representative of A Corp.

- The Performance Contract: X and A Corp. entered into a "Performance Contract." Under this agreement, X acquired the rights to invite A Corp.'s circus to Japan for performances over two years (1988-1989). X was to pay A Corp. a fee, and A Corp. undertook to organize and perform a circus in Japan of a scale and quality comparable to its 1987 San Diego performance.

- X's Lawsuit Against Y (A Corp.'s Representative): Subsequently, X filed a lawsuit in a Japanese court, not against A Corp. (the other party to the contract), but against Y, A Corp.'s representative. X alleged that during the negotiation of the Performance Contract, Y had committed tortious acts (fraud) by deceiving X regarding matters such as the distribution of profits from character merchandise sales and the allocation of costs for animal tent construction, thereby causing X to suffer damages.

- Y's Defense: Y argued that the Arbitration Agreement between X and A Corp. should extend to cover this tort claim against him (as A Corp.'s representative) and, therefore, X's lawsuit in court was improper and should be dismissed in favor of arbitration.

The Arbitration Agreement: At the time of signing the Performance Contract, X and A Corp. also included an arbitration clause ("the Arbitration Agreement"). This clause stipulated:

"If any dispute including the interpretation or application of the terms of this Performance Contract cannot be resolved, such dispute shall, upon written request of a party, be submitted to arbitration in accordance with the Rules and Procedures of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) concerning commercial dispute arbitration. All arbitration proceedings initiated by A [Corp.] shall be held in Tokyo, and all arbitration proceedings initiated by X shall be held in New York City. Each party shall bear its own costs related to arbitration, provided, however, that the parties shall equally bear the arbitrator's fees and expenses."

The Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court both agreed with Y, dismissing X's lawsuit on the grounds that the dispute fell under the arbitration agreement. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Questions

The Supreme Court was tasked with addressing several key issues:

- What law should govern the validity and scope of this international arbitration agreement?

- Does an arbitration agreement between two companies (X and A Corp.) also cover related tort claims brought by one company (X) against the representative (Y) of the other company (A Corp.), particularly when the representative is not a direct signatory to the arbitration agreement?

- If a dispute is found to be covered by a valid arbitration agreement, what is the proper action for a national court when a lawsuit is filed in breach of that agreement?

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions to dismiss the lawsuit in favor of arbitration. Its reasoning provided significant guidance:

1. Governing Law of the International Arbitration Agreement (Party Autonomy):

The Court began by emphasizing the consensual nature of arbitration. Since arbitration is a dispute resolution method founded on the parties' agreement to submit their disputes to arbitrators rather than courts:

- The formation and validity of an international arbitration agreement should, in the first instance, be determined by the governing law chosen by the parties. This aligns with the principle of party autonomy in contract law, as recognized by Article 7(1) of Japan's Horei (the old Act on Application of Laws, the principles of which are now in Article 7 of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws).

- Even if the parties have not made an express choice of law for the arbitration agreement itself, an implied choice of law can be inferred from the circumstances. Factors such as an agreement on the place of arbitration (仲裁地 - chūsai chi), the content of that agreement, the nature of the main contract to which the arbitration clause relates, and other relevant details should be considered.

2. Implied Choice of Governing Law in This Case (Law of the Arbitral Situs):

Applying these principles:

- The Arbitration Agreement between X and A Corp. did not contain an express clause stating which country's law would govern the arbitration agreement itself.

- However, the agreement did specify the place of arbitration, employing a "cross-arbitration clause": arbitrations initiated by A Corp. were to be held in Tokyo, while arbitrations initiated by X were to be held in New York City.

- The Supreme Court reasoned that, considering X initiated the dispute (which, if arbitrated by X, would be in New York), it was appropriate to infer that the parties had impliedly agreed that the law applicable in New York City (the designated arbitral situs for X's claims) would be the governing law of the arbitration agreement with respect to disputes brought by X.

3. Scope of the Arbitration Agreement Under the Chosen Law (U.S. Federal Arbitration Act):

The Court then identified the law applicable in New York City for such arbitrations as the U.S. Federal Arbitration Act (FAA).

- Based on an interpretation of the FAA and relevant U.S. federal court precedents concerning the substantive scope (types of disputes covered) and personal scope (parties bound) of arbitration agreements, the Supreme Court concluded that the Arbitration Agreement between X and A Corp. did indeed extend to cover X's tort claim for damages against Y (A Corp.'s representative). This was despite Y not being a direct signatory, because the tort claims were closely intertwined with the Performance Contract and its negotiation.

- Effect of a Valid Arbitration Agreement on Court Proceedings (Dismissal): The Court stated that the scope of disputes that must be referred to arbitration if a party so requests, and the scope of disputes for which a court lawsuit can be dismissed due to the existence of an arbitration agreement, should be coextensive—they are two sides of the same coin.

- Therefore, since X's claim against Y fell within the scope of the valid arbitration agreement (as interpreted under U.S. law), Y's defense invoking this agreement was upheld. X's lawsuit was deemed inadmissible for lacking a legitimate interest or benefit of suit (訴えの利益を欠く - uttae no rieki o kaku) in pursuing court litigation instead of the agreed-upon arbitration.

Significance and Commentary Insights

This 1997 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for international arbitration in Japan:

- Affirmation of Party Autonomy: It strongly affirmed the principle of party autonomy in determining the law applicable to the arbitration agreement itself, giving significant weight to the parties' express or implied intentions.

- Role of Arbitral Situs in Implied Choice: The judgment highlighted the agreed place of arbitration as a key indicator for inferring an implied choice of law for the arbitration agreement. However, Professor Nakamura's commentary notes that inferring such a choice solely from the situs can be complex, particularly with "cross-arbitration clauses" where the situs varies depending on which party initiates the arbitration, as it may be difficult to pinpoint a single, unified implied intent for the governing law of the agreement's validity.

- Broad Interpretation of an Arbitration Agreement's Scope (Under the Chosen Law): The decision demonstrated a willingness by Japanese courts to recognize that, if the chosen governing law of the arbitration agreement (like the U.S. FAA) allows it, arbitration clauses can extend to cover related tort claims and even bind non-signatories who are closely connected to the contract or the dispute (such as a representative of a contracting party).

- Procedural Consequence of a Valid Arbitration Agreement: The ruling confirmed that the proper response of a Japanese court, when faced with a lawsuit brought over a dispute that is covered by a valid international arbitration agreement, is to dismiss the court action if a party raises the arbitration agreement as a defense (a plea in bar - 妨訴抗弁, bōso kōben).

- Debate on Theoretical Basis for Governing Law: Academic commentary, such as by Professor Nakamura, notes ongoing discussion about the most appropriate theoretical basis for choosing the law governing the arbitration agreement. While the Supreme Court applied the general contract choice-of-law rules (Horei Art. 7), some scholars argue for rules derived more directly from international arbitration conventions like the New York Convention or from Japan's own Arbitration Act, to ensure consistency across different phases of the arbitral process (e.g., initial court referral, arbitral proceedings, enforcement or setting aside of awards).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1997 "Ringling Bros." decision significantly bolstered the standing and enforceability of international arbitration agreements in Japan. It underscored the judiciary's respect for party autonomy in choosing arbitration as a dispute resolution mechanism and in selecting the law that governs their arbitration agreement. By confirming that Japanese courts will dismiss lawsuits initiated in defiance of valid arbitration agreements, even when those agreements extend to related tort claims or involve non-signatories under the applicable foreign law, the Court reinforced Japan's position as an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction. This case remains a vital precedent for parties involved in international contracts with Japanese connections.