Resolving Corporate Deadlock in Japan: Understanding Judicial Dissolution Procedures

TL;DR

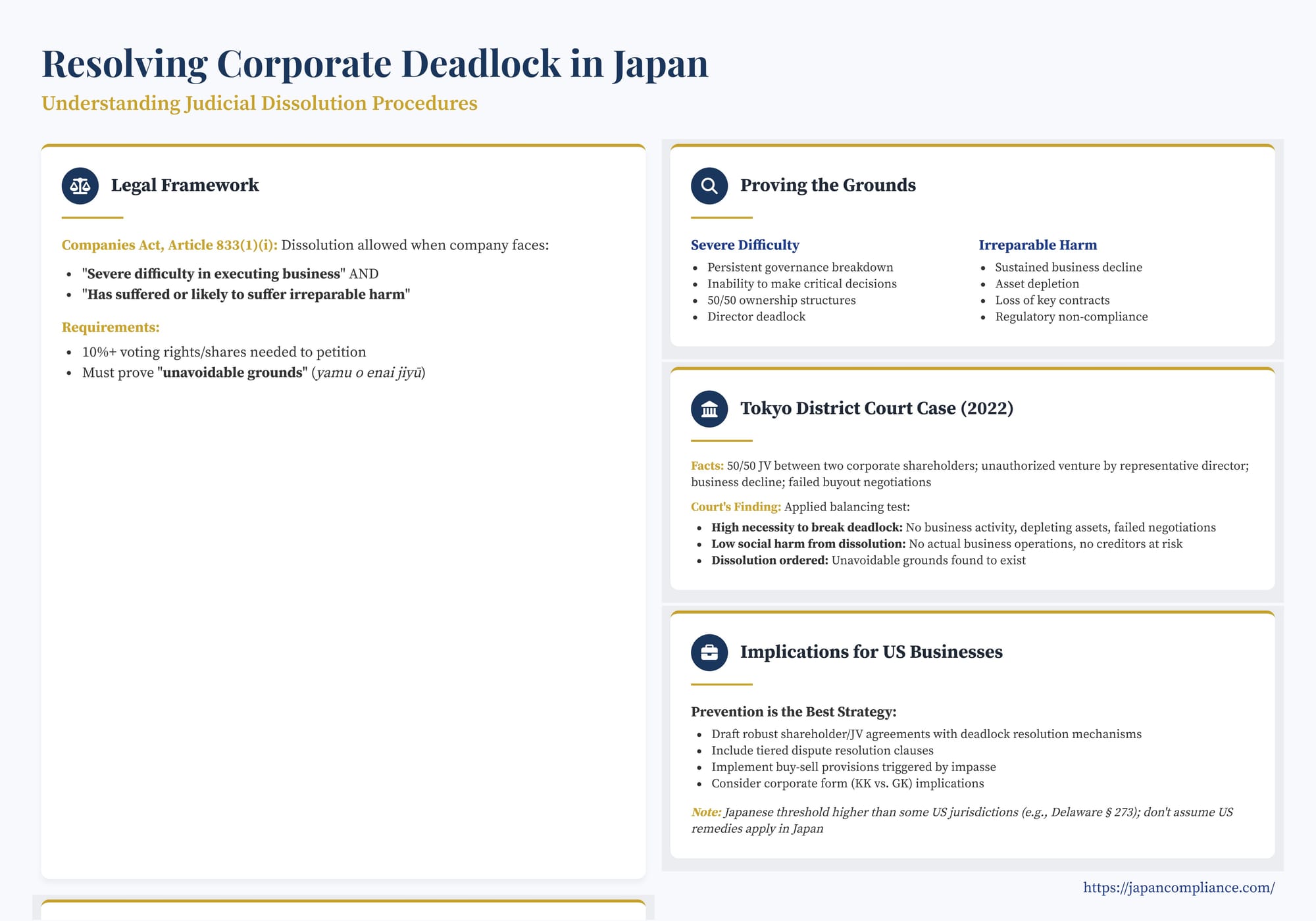

- Japan’s Companies Act lets 10 %+ shareholders petition for judicial dissolution when deadlock causes severe business paralysis and irreparable harm.

- Courts apply a strict two-step test—prove “severe difficulty” and likely irreparable damage—plus a balancing test of “unavoidable grounds.”

- A 2022 Tokyo decision shows the court weighing the need to end stalemate against social loss, ordering dissolution when business had stalled and assets were depleting.

- Robust shareholder or JV agreements with multi-tier dispute clauses and buy-sell mechanics remain the best way to avoid litigation.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Challenge of Corporate Impasse

- The Legal Framework: Judicial Dissolution under the Companies Act

- Proving “Severe Difficulty” and “Irreparable Harm”

- The Crucial Hurdle: “Unavoidable Grounds”

- Practical Implications for US Businesses

- Conclusion: Prevention Is the Best Strategy

Introduction: The Challenge of Corporate Impasse

Corporate deadlock, a situation where shareholders or directors are so fundamentally divided that the company's management and operations grind to a halt, is a significant risk, particularly in closely-held corporations and joint ventures. For US businesses participating in 50/50 joint ventures or holding significant minority stakes in Japanese corporations (kabushiki kaisha or KK), understanding how Japanese law addresses such impasses is crucial. While well-drafted shareholder or joint venture agreements should provide mechanisms to resolve disputes, situations can arise where these mechanisms fail or are absent, leading to paralysis.

In such extreme circumstances, Japan's Companies Act provides a potential remedy of last resort: judicial dissolution. A shareholder holding ten percent or more of the voting rights or issued shares can petition a court to dissolve the company if certain stringent conditions are met. This article explores the legal framework for judicial dissolution due to deadlock in Japan, analyzes a key recent court decision illustrating its application, and discusses practical implications for US businesses involved in Japanese corporate structures.

The Legal Framework: Judicial Dissolution under the Companies Act

The primary statutory basis for court-ordered dissolution of a KK is Article 833, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act. While the article lists several grounds, the two most relevant to operational paralysis or internal conflict are:

- Article 833(1)(i): When a company faces "severe difficulty in executing its business" (業務の執行において著しく困難な状況 – gyōmu no shikkō ni oite ichijirushiku konnan na jōkyō) AND "has suffered or is likely to suffer irreparable harm" (回復することができない損害が生じ、又は生ずるおそれがある – kaifuku suru koto ga dekinai songai ga shōji, mata wa shōzuru osore ga aru). This is the typical ground invoked in deadlock scenarios.

- Article 833(1)(ii): When the "management or disposition of company property is extremely improper, threatening the existence of the Stock Company" (株式会社の財産の管理又は処分が著しく失当であり、当該株式会社の存立を危うくするとき – kabushiki-gaisha no zaisan no kanri mata wa shobun ga著shiku shittō de ari, tōgai kabushiki-gaisha no sonritsu o ayauku suru toki). This relates more to mismanagement or asset stripping.

Critically, even if the conditions under item (i) or (ii) are met, dissolution is not automatic. The overarching requirement, stated in the main clause of Article 833(1), is that there must be "unavoidable grounds" (やむを得ない事由 – yamu o enai jiyū) for dissolution. The interpretation and application of this "unavoidable grounds" requirement are central to understanding the high threshold for judicial dissolution in Japan.

Proving the Grounds: "Severe Difficulty" and "Irreparable Harm"

Establishing the conditions under Article 833(1)(i) in a deadlock case requires demonstrating both elements:

- Severe Difficulty in Executing Business: This typically arises in 50/50 ownership structures where shareholders cannot reach the necessary majority for critical decisions at shareholder meetings (e.g., electing directors). It can also occur if directors themselves are deadlocked and unable to manage the company's affairs effectively. The court looks for evidence that fundamental corporate governance mechanisms have broken down due to the impasse, making effective management impossible. Temporary disagreements are insufficient; the deadlock must be persistent and profound.

- Irreparable Harm (Actual or Potential): This involves showing significant negative consequences stemming from the deadlock. Mere difficulty in operating is not enough. Evidence might include a sustained decline in business performance, inability to pursue necessary business strategies, depletion of corporate assets due to ongoing expenses without corresponding revenue, loss of key employees or contracts, or inability to comply with legal or regulatory obligations. The harm must be substantial and not easily remedied if the deadlock persists.

The Crucial Hurdle: "Unavoidable Grounds" (Yamu o Enai Jiyū)

Historically, Japanese courts and legal commentators often interpreted the "unavoidable grounds" requirement strictly, primarily focusing on whether dissolution was the only remaining option to protect the petitioning shareholder's legitimate interests. If other potential remedies existed, such as the petitioner selling their shares (even if difficult or at an unfavorable price), dissolution might be denied.

However, a recent court decision highlights a potentially more nuanced approach, explicitly adopting a balancing test to evaluate "unavoidable grounds."

Analysis of a Recent Case (Tokyo District Court, Tachikawa Branch, September 9, 2022)

This case involved a KK established as a joint venture, with ownership split 50/50 between two corporate shareholders (let's call them Shareholder X and Shareholder Y, the latter controlled by individual A). Shareholder X petitioned for dissolution under Article 833(1)(i).

- Facts Leading to Deadlock: The company was initially formed to sell specific electrical products manufactured by Shareholder X. However, individual A, representing Shareholder Y and serving as the company's representative director, began pursuing an unrelated and unauthorized agribusiness venture. This led to a neglect of the original business, a sharp decline in sales, and eventually, lawsuits between Shareholder X and the company (represented by A/Shareholder Y) over the transfer of the original business rights. The company ceased generating revenue, relying solely on its cash reserves, which were steadily decreasing to cover ongoing expenses. Attempts by Shareholder X and Shareholder Y to negotiate a resolution, including a potential buyout of X's shares, failed due to disagreements over valuation.

- Court's Findings on Art. 833(1)(i): The court easily found the existence of "severe difficulty in executing business," given the 50/50 shareholding structure and the complete breakdown of trust and communication between the shareholders, making majority decisions impossible. It also found "irreparable harm or risk thereof," citing the cessation of the company's primary business, the lack of any actual sales from the new agribusiness venture, and the continuous depletion of the company's main asset (cash) with no prospect of recovery.

- The "Unavoidable Grounds" Balancing Test: Crucially, the court articulated its approach to the yamu o enai jiyū requirement. It stated that this condition is generally met if the necessity of breaking the deadlock outweighs the necessity of avoiding the social loss that would result from the company's dissolution, unless exceptional circumstances warrant otherwise.

- Necessity of Breaking Deadlock: The court found this necessity to be high. Shareholder X's legitimate interests were being harmed by the ongoing paralysis and asset depletion. Importantly, the court noted that there was no realistic prospect of Shareholder X selling its shares to Shareholder Y or a third party, given the conflict and the company's situation. Therefore, dissolution appeared to be the only viable way to resolve the stalemate and protect Shareholder X.

- Necessity of Avoiding Social Loss: The court found this necessity to be low. The company's new agribusiness venture had not reached the sales stage, meaning dissolution would not disrupt an ongoing, viable business. Furthermore, the company had no trade creditors or financial institution creditors who would be harmed. The court also observed that individual A (representing Shareholder Y) could potentially use the residual assets distributed upon liquidation to establish a new company and pursue the agribusiness if desired, minimizing the loss of the business concept itself and potentially preserving employment (though the existence of employees was unclear from the facts).

- Conclusion: Balancing these factors, the court concluded that the need to break the deadlock significantly outweighed the social loss associated with dissolution. Finding no exceptional circumstances, it ruled that "unavoidable grounds" existed and ordered the company's dissolution.

Significance of the Balancing Test: This decision is noteworthy for its explicit adoption and application of the balancing test for "unavoidable grounds." While the lack of alternative remedies for the petitioner remains a key factor (contributing to the high necessity of breaking the deadlock), the test potentially allows courts to consider a broader range of factors, including the impact on third parties (creditors, employees) and the viability of the underlying business, in a more structured way. This might offer slightly more flexibility than interpretations focusing solely on the petitioner's lack of exit options, although judicial dissolution remains an extraordinary remedy granted only in compelling circumstances. It acknowledges that even in a deadlock, if the company remains viable and its dissolution would cause significant harm to stakeholders or the wider economy, the balance might tip against ordering dissolution.

Practical Implications for US Businesses

The Japanese legal framework and the case law surrounding judicial dissolution offer several key takeaways for US companies involved in Japanese ventures:

- Prioritize Deadlock Prevention in Agreements: The high bar and uncertainty associated with judicial dissolution underscore the critical importance of robust deadlock resolution mechanisms in shareholder agreements or joint venture agreements. Relying on statutory remedies should be a last resort. Effective agreements might include:

- Clearly defined scopes of authority for directors and matters requiring special shareholder approval.

- Tiered dispute resolution clauses (e.g., senior management negotiation, mediation, then arbitration or expert determination).

- Buy-sell provisions triggered by deadlock (e.g., Russian roulette clauses, sealed bid auctions, rights of first refusal/offer).

- Clauses specifying consequences of deadlock, potentially leading to a structured wind-down or exit.

- Understand the High Threshold for Dissolution: Judicial dissolution in Japan is not easily granted. Courts view it as a drastic measure and require compelling evidence of both severe operational difficulty and irreparable harm, coupled with "unavoidable grounds." Simply disagreeing with a partner or facing temporary business challenges is highly unlikely to meet the standard.

- Document Difficulties and Harm: If facing a genuine deadlock, meticulously document the inability to make decisions, the specific business harm resulting from the paralysis (e.g., lost opportunities, asset depletion, operational failures), and attempts made to resolve the dispute through negotiation or contractual mechanisms. This evidence is crucial if judicial dissolution becomes the only remaining option.

- Explore All Alternatives: Before petitioning for dissolution, explore and, where feasible, attempt alternative solutions, such as negotiating a buyout, seeking mediation, or proposing restructuring. Demonstrating that other avenues have been exhausted strengthens the argument for "unavoidable grounds."

- Consider the Corporate Form: While this discussion focuses on KKs, the most common form for JVs involving foreign parties, similar deadlock issues can arise in gōdō kaisha (GK), a form resembling a US LLC. GKs offer more flexibility in governance structure, potentially allowing for clearer deadlock resolution provisions in the operating agreement, but statutory remedies for deadlock might differ.

- Comparison with US Law: The Japanese approach appears generally more conservative than in some US jurisdictions. For example, Delaware law provides specific, potentially more streamlined procedures for dissolving deadlocked 50/50 joint ventures (DGCL § 273) and allows courts broader discretion to order dissolution in cases of director/shareholder deadlock impairing the business or where shareholders are unable to elect directors (DGCL § 226). Some US state statutes also permit dissolution based on shareholder oppression, a concept less developed in Japanese statutory law for dissolution. US parties should not assume that remedies available in the US will be mirrored in Japan.

Conclusion: Prevention is the Best Strategy

Judicial dissolution offers a potential, albeit drastic, solution to intractable corporate deadlock in Japan under Article 833 of the Companies Act. As demonstrated by recent case law, courts require proof of severe operational difficulty and irreparable harm, and will carefully weigh the necessity of breaking the impasse against the potential negative consequences of dissolution under the "unavoidable grounds" standard.

Given the high threshold and inherent uncertainties of litigation, the most effective strategy for US businesses entering Japanese joint ventures or closely-held corporations is prevention. Investing time and resources in negotiating comprehensive shareholder or joint venture agreements with clear governance structures and robust, multi-tiered deadlock resolution mechanisms is paramount. While the Japanese Companies Act provides a safety valve for truly unavoidable situations, relying on it should be viewed as a measure of last resort after all contractually agreed methods have failed. Proactive planning remains the best defense against the potentially value-destroying consequences of corporate paralysis.

- Director Liability in Japan: A Case Study Involving Attorney Directors and M&A

- Board Discretion and Director Accountability in Japan: Insights from a 2024 Supreme Court Ruling

- Mergers & Acquisitions in Japan: A Legal and Practical Guide for US Businesses

- Ministry of Justice | English Translation of the Companies Act

https://japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/3303 - Supreme Court of Japan | English Judgments Search Page

https://www.courts.go.jp/english/judgments/