Resisting a Mistaken Arrest: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Lawful" Police Actions

Imagine a chaotic scene on the street. Police are making an arrest, and in the confusion, they attempt to arrest a second person who you believe is an innocent bystander. If that person resists, are they committing a crime? Or consider a more personal scenario: you are being arrested by the police, but you know with absolute certainty that you have done nothing wrong. Is it your right to physically resist what you know to be a mistaken, and therefore "unlawful," arrest?

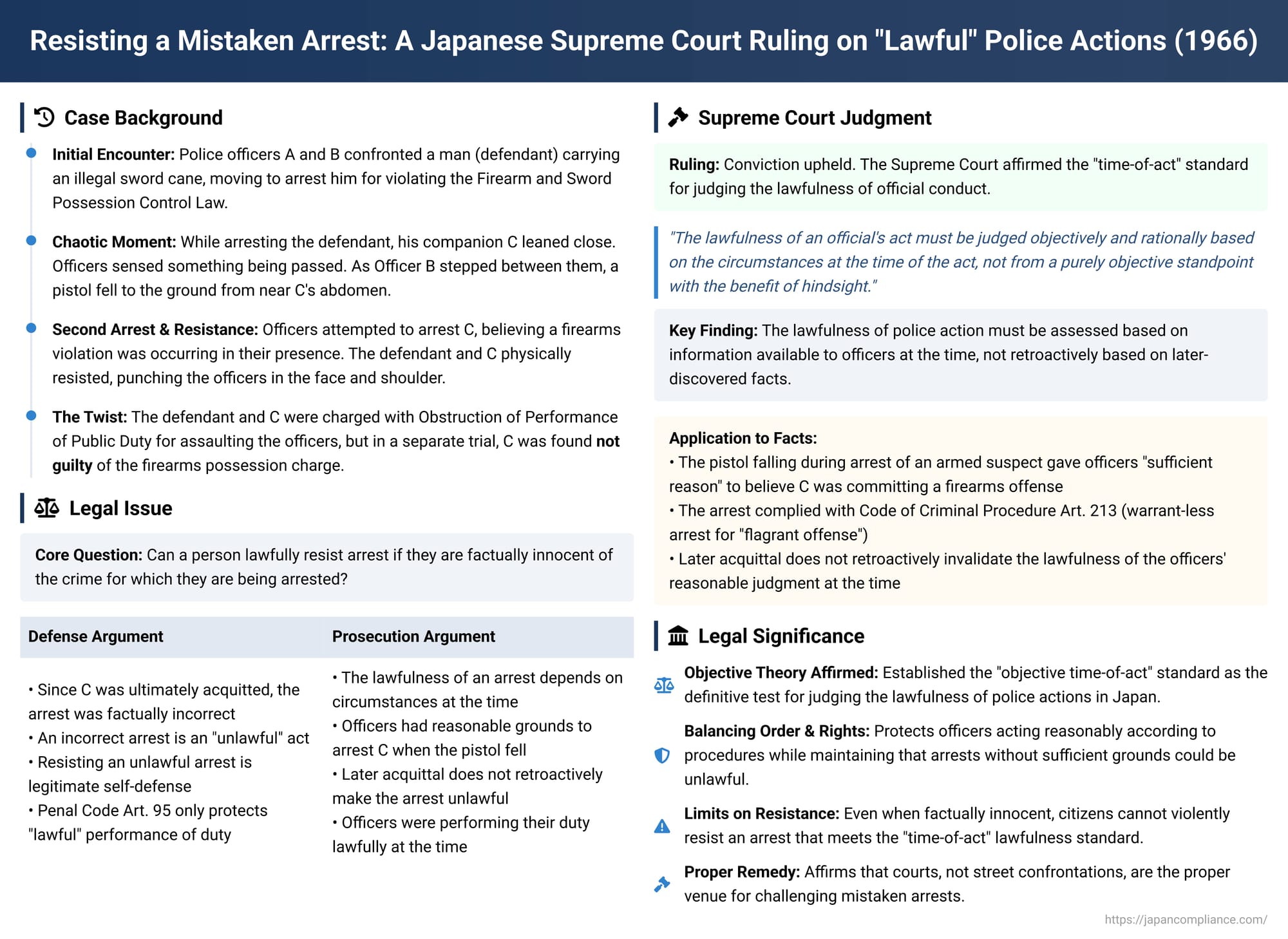

This critical question—what constitutes a "lawful" performance of public duty, and whether a citizen can legally resist an official who is making a reasonable mistake—was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 14, 1966. The ruling established the definitive standard for judging the legality of a police officer's actions, emphasizing a pragmatic, on-the-ground assessment rather than a standard of perfect, after-the-fact knowledge.

The Facts: The Sword Cane and the Falling Pistol

The case arose from a tense street encounter between two police officers and two individuals.

- The Initial Encounter: Officers A and B, while on patrol, confronted a man (the defendant) because he was in possession of an illegal sword cane. They moved to arrest him for violating the Firearm and Sword Possession Control Law.

- A Chaotic Moment: During the attempt to arrest the defendant, his companion, C, leaned in close. The officers sensed that the defendant was passing something to C. Officer B stepped between them, at which point a pistol fell to the ground from near C's abdomen.

- The Second Arrest and Resistance: Believing C was now also committing a firearms violation in their presence, the officers attempted to arrest him as well. The defendant and C resisted this arrest violently, punching the officers in the face and shoulder.

- The Twist: The defendant and C were charged with Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty for assaulting the officers. However, in a separate trial, C was ultimately found not guilty of the firearms possession charge. He was, in fact, innocent of the crime for which he was being arrested.

The Legal Defense: Resisting an "Unlawful" Arrest

The defense's argument was built on C's eventual acquittal.

- They argued that since C had committed no crime, the officers' attempt to arrest him was factually incorrect and therefore an "unlawful" act.

- The crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty (Penal Code Art. 95) only protects the lawful performance of duty.

- Therefore, they contended, resisting this unlawful arrest was a legitimate act of self-defense, not a crime.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Time-of-Act" Standard

The Supreme Court rejected the defense's argument and upheld the convictions, tacitly affirming the reasoning of the High Court. The High Court had established what is now known as the "time-of-act" standard for judging the lawfulness of an official's conduct.

The core of this ruling is that the lawfulness of an official's act must be judged "objectively and rationally based on the circumstances at the time of the act," not from a "purely objective standpoint with the benefit of hindsight."

Applying this standard to the facts, the Court found:

- At the moment the pistol fell from C's person during the arrest of another armed suspect, the officers had "sufficient reason" to believe C was committing a firearms offense in their presence (a "flagrant offense").

- Based on the information available to the officers at that time, their judgment was reasonable, and their attempt to arrest C was therefore a lawful performance of their duties.

- The fact that a court later acquitted C does not retroactively invalidate the lawfulness of the officers' on-the-spot decision.

Analysis: The Legal Framework for Official Action

This decision is of immense importance because it solidifies a pragmatic and necessary approach to the lawfulness of police conduct. It firmly places Japanese jurisprudence in the camp of what legal scholars call the "objective theory" for judging lawfulness, while specifying that the objective assessment must be based on the circumstances at the time of the act.

- The Legal Basis in the Code of Criminal Procedure: The Court's reasoning is deeply grounded in the legal framework for arrests in Japan. The Code of Criminal Procedure (Art. 213) authorizes a police officer to conduct an arrest without a warrant for a "flagrant offense" (genkōhan). The standard for such an arrest is not that the person is definitively guilty, but that there are sufficient grounds at the time for the officer to believe they are committing or have just committed a crime. The law itself anticipates the possibility of reasonable mistakes made in the heat of the moment and deems an arrest that meets this standard to be lawful. The officers' actions were lawful because they complied with the requirements of the Code of Criminal Procedure. To hold police to a standard of perfect, retroactive knowledge would paralyze law enforcement and make it impossible for officers to act decisively to ensure public safety.

- A Balance Between Order and Rights: This standard strikes a crucial balance. It protects public officials from violent interference when they are acting reasonably and in accordance with established legal procedures. At the same time, it does not give them unlimited power; an arrest made without sufficient objective grounds at the time would indeed be unlawful and could be legally resisted.

- The Limits of Resistance: It is important to note that even when an arrest is based on a mistake of fact, if it is deemed "lawful" under the time-of-act standard, resistance is not permitted. However, legal commentary suggests a small degree of nuance. While the law protects the official function, later court decisions have hinted that an "extremely slight" physical reaction by an innocent person against a mistaken (though technically lawful) arrest might not meet the definition of "assault or intimidation" required for the crime of obstruction. This offers a small acknowledgment of the difficult position a wrongly accused person is in. The violent punching in this case, however, clearly went far beyond such minor resistance.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1966 decision established the "objective time-of-act" standard as the definitive test for judging the lawfulness of a police officer's actions in Japan. The ruling makes clear that an official's act is legally protected if it was objectively reasonable based on the circumstances as they appeared at that moment. The subsequent discovery that the citizen was innocent does not retroactively make the officer's initial action unlawful. This case provides a crucial lesson in the rule of law: it protects public officials from violence when they act reasonably within their authority, and it affirms that the proper venue to challenge a mistaken arrest is in a court of law, not through physical resistance on the street.