Japan Supreme Court on Undocumented Residents’ NHI Eligibility & State Liability (2004)

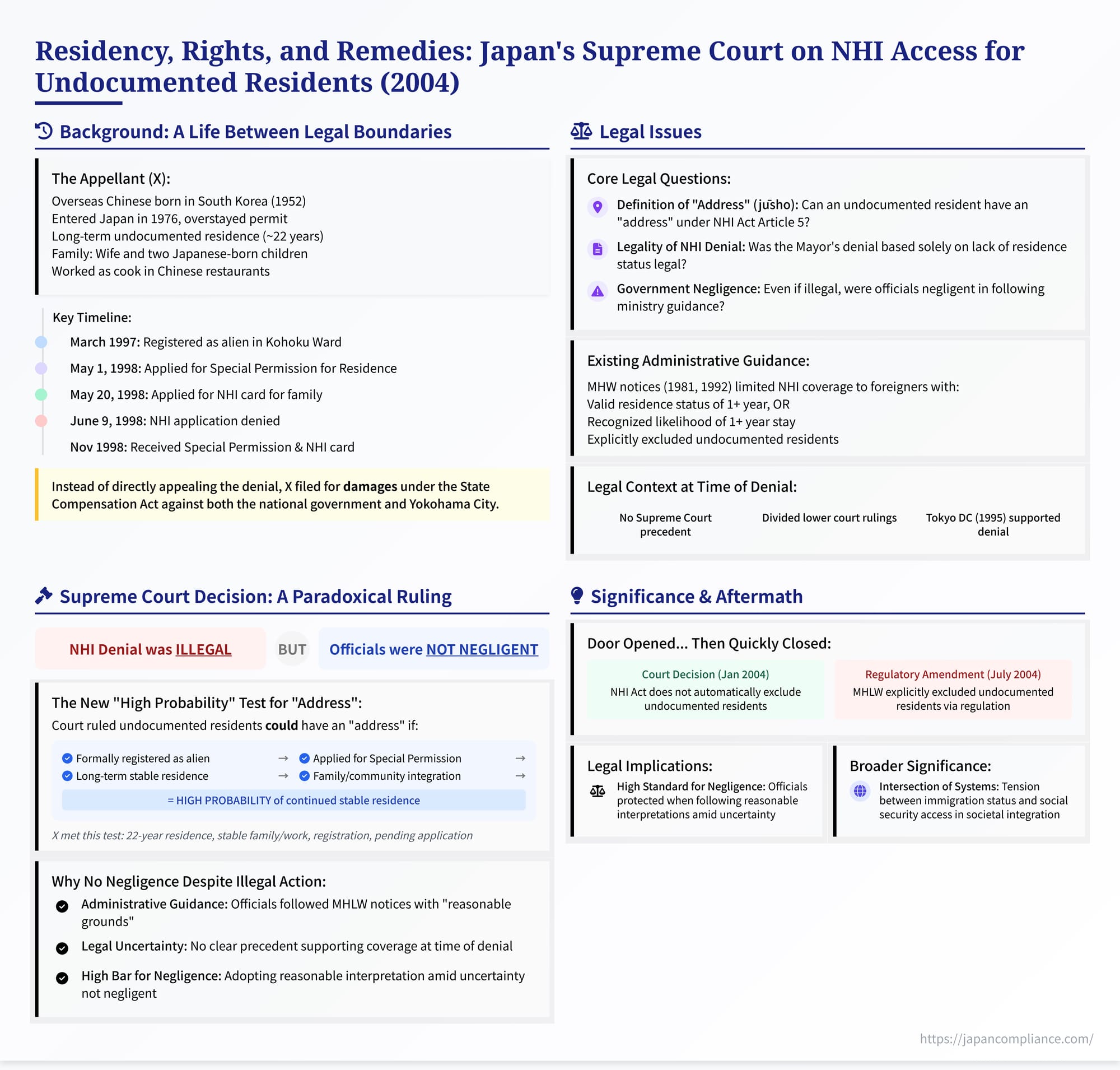

TL;DRThe 2004 ruling held that an undocumented long‑term resident who had registered locally and applied for Special Permission for Residence could, in rare cases, meet the “address” requirement of Japan’s National Health Insurance Act.The denial of NHI coverage in the case was therefore illegal, yet no damages were awarded because officials relied on then‑reasonable ministry guidance—no negligence was found.A 2004 regulatory amendment soon after the judgment now explicitly excludes undocumented residents from NHI, closing the door the Court briefly opened.

Table of Contents

- Background: A Life Lived Between Legal Boundaries

- The Denial of NHI Coverage

- The Legal Challenge: Seeking Damages for Wrongful Denial

- The Supreme Court's Nuanced Decision: Illegal Denial, But No Negligence

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

The intersection of immigration status and access to social security systems presents profound legal and humanitarian challenges worldwide. When individuals reside and contribute to a society without formal legal status, what rights, if any, do they have to essential services like healthcare funded through public insurance schemes? Furthermore, if government officials deny access based on a particular interpretation of the law, can the government be held liable for damages if that interpretation is later found incorrect by the courts? A significant 2004 decision by Japan's Supreme Court delved into these complex questions in the context of the National Health Insurance (NHI) system and an undocumented foreign resident's claim. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Damages (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Heisei 14 (Ju) No. 687, Jan. 15, 2004), offers a nuanced perspective on the definition of "residence" for NHI eligibility, the potential scope of coverage for undocumented individuals under specific circumstances, and the stringent requirements for establishing government negligence in state compensation lawsuits.

Background: A Life Lived Between Legal Boundaries

The appellant, X, had a complex personal history reflecting geopolitical shifts. Born in South Korea in 1952 to parents identified as "overseas Chinese," X initially entered Japan in 1971 on a short-term visa to visit relatives. Having failed to secure re-entry permission from South Korea before leaving, X lost permanent residency status there. After attempting to settle in Taiwan proved unsuccessful due to nationality documentation issues and language barriers, X re-entered Japan in 1976 under a temporary shore pass (permitting a 72-hour stay). X overstayed this permission and remained in Japan without legal status, working primarily as a cook in Chinese restaurants.

Despite the lack of formal residency status, X built a life in Japan. In 1977, X married a Taiwanese woman. The couple had two children, a son born in 1979 and a daughter in 1981, both born in Japan. The wife and children also traveled between Japan and Taiwan in attempts to secure legal status but eventually overstayed their short-term visas after entering Japan in July 1984, joining X as undocumented residents. The family resided together in Kohoku Ward, Yokohama City, from approximately December 1985 until December 2000.

X made efforts to regularize his status. He presented himself to the Immigration Bureau in 1994 and 1996. However, difficulties in confirming his nationality (given his background) complicated matters, and after several inquiries by immigration officials, contact ceased without resolution. In March 1997, X formally registered as an alien with the Kohoku Ward office, a necessary step for residents but distinct from having a valid immigration status. At that time, X requested an NHI card but was denied.

A critical turning point came when X's son was diagnosed with a brain tumor. Seeking stable access to healthcare and legal status, X, along with his wife and children, submitted a formal application for Special Permission for Residence (zairyū tokubetsu kyoka)—a discretionary measure allowing the Minister of Justice to grant legal status to undocumented individuals under exceptional circumstances—at the Yokohama Immigration office on May 1, 1998.

Shortly thereafter, on May 20, 1998, X again applied to the Kohoku Ward Mayor (acting under delegation from Yokohama City, the NHI insurer) for an NHI card for himself and his family.

The Denial of NHI Coverage

On June 9, 1998, the Kohoku Ward Mayor issued a disposition (本件処分, honken shobun) formally denying X's request for an NHI card. The sole reason given was that X lacked a valid residence status (zairyū shikaku) and therefore did not meet the definition of an insured person under Article 5 of the National Health Insurance Act (NHI Act).

This denial was consistent with administrative guidance issued by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MHLW) through official notices (本件各通知, honken kaku tsūchi) in 1981 and 1992. These notices interpreted the NHI Act's coverage for foreigners (following the removal of the explicit nationality requirement in the related regulations in 1986) as being limited to registered foreigners who possessed a valid residence status allowing a stay of one year or more, or those with shorter initial stays who were nevertheless recognized as likely to reside for over a year based on their circumstances. The notices did not envision coverage for undocumented residents. At the time of the denial in 1998, the legal interpretation of whether NHI Act Article 5 could cover undocumented residents was unsettled; there was no definitive Supreme Court precedent, lower court rulings were divided, and the most prominent existing ruling (a 1995 Tokyo District Court decision) supported the government's position denying coverage.

The Legal Challenge: Seeking Damages for Wrongful Denial

X did not directly challenge the denial処分 (shobun) itself through administrative appeal lawsuits (likely because the family's status changed soon after). Instead, X filed a lawsuit seeking damages against both the State (Y1, Government of Japan) and Yokohama City (Y2) under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act (国家賠償法, Kokka Baishō Hō). This Act allows individuals to seek compensation when they suffer damages due to the illegal conduct (intentional or negligent) of public officials in the exercise of public authority.

X argued that:

- The denial of the NHI card was illegal because, despite lacking formal status, X's long-term, stable residence in Yokohama qualified him as a person having an "address" (jūsho) within the municipality's area under NHI Act Article 5, making him eligible for coverage.

- The illegality stemmed from negligence by both levels of government:

- The State (Y1) was negligent in issuing administrative notices (本件各通知) based on an incorrect interpretation of Article 5.

- The Kohoku Ward Mayor (acting for Y2 Yokohama City) was negligent in following this incorrect guidance and issuing the illegal denial処分.

- This illegal denial caused X financial damages (e.g., higher out-of-pocket medical expenses for his son's treatment due to the lack of insurance coverage).

(Note: The family did eventually receive Special Permission for Residence with "long-term resident" status for one year in November 1998. Yokohama City issued NHI cards to them the following day.)

The lower courts reached different conclusions on the legality of the denial but both ultimately denied damages. The Tokyo District Court found the denial illegal (agreeing X met the "address" requirement) but found no negligence. The Tokyo High Court found the denial legal (holding "address" requires legal status) and therefore found no basis for damages. X appealed the denial of damages to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Nuanced Decision: Illegal Denial, But No Negligence

The First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered a nuanced judgment. It agreed with the District Court that the denial of the NHI card was illegal, overturning the High Court on this point. However, it agreed with both lower courts that the officials involved were not negligent, thus denying X's claim for damages and ultimately dismissing the appeal.

1. Reasoning on the Illegality of the Denial (Interpretation of NHI Act Article 5 "Address"):

This part of the decision represented a significant development in interpreting NHI eligibility for foreigners.

- "Address" Defined: The Court started by defining "address" (jūsho) under Article 5, consistent with general legal principles, as the "principal place of life" (seikatsu no honkyo), determined by objective facts of residence combined with the individual's subjective intent to reside there continuously and stably.

- Foreigners Not Automatically Excluded: The Court explicitly stated that Article 5 does not contain language that automatically excludes all non-Japanese nationals without legal residence status. It noted the historical context: the explicit exclusion of foreigners in the implementing regulations was removed in 1986. While acknowledging a general principle that social security systems based on solidarity might primarily target legal residents, the Court emphasized that the specific scope of coverage for each system is a matter of legislative policy. The legislative history of the NHI Act did not support reading an inherent exclusion of all undocumented residents into Article 5. Furthermore, since NHI is largely funded by premiums, including undocumented residents was not fundamentally contrary to the purpose of the insurance scheme itself. (Crucially, however, the Court added in parenthesis that it would be permissible for the legislature or administration to explicitly exclude undocumented residents via regulations or ordinances based on the general principle favoring legal residents – a point that foreshadowed later regulatory changes).

- Importance of Residence Status: While lack of legal status isn't an automatic bar, the Court stressed that an individual's immigration status (possession of a visa, duration, legality) is a critically important factor in assessing whether their residence meets the "continuity and stability" requirement inherent in the Article 5 definition of "address." Undocumented residents face potential deportation, making their residency inherently precarious under immigration law.

- The New Test for Undocumented Residents: Synthesizing these points, the Court established a new, specific test for when an undocumented foreigner could be deemed to have an "address" under Article 5:

- Merely residing physically is insufficient.

- The individual must at least:

- Be registered as an alien in the municipality (indicating some formal connection and intent to reside).

- Have formally applied for Special Permission for Residence under Immigration Control Act Article 50 (signaling an active attempt to regularize status and intent to remain).

- AND, based on a holistic assessment of various factors, there must be a "high probability" (gaizensei ga takai) that the individual is continuously maintaining a stable life within the municipality and will continue to do so in the future. Factors to consider include:

- Circumstances of entry and becoming undocumented.

- Past/present visa status and duration.

- Family circumstances (spouse, children, their nationality/status).

- Length of stay in Japan/the municipality.

- Current living situation (employment, community ties, etc.).

- Application to X: Applying this test to X's specific circumstances, the Court found he met the criteria. Despite lacking legal status: [1] His situation was somewhat unique (statelessness issues); [2] He had tried to regularize his status; [3] His residency was extremely long-term (~22 years total, ~13 in Yokohama); [4] He had stable family life and employment; [5] He was registered and had applied for special permission; [6] That permission was indeed granted shortly after. These factors combined indicated a high probability of continued stable residence.

- Conclusion on Illegality: Therefore, the Court concluded, X did meet the requirements of having an "address" under Article 5 at the time of his application. Consequently, the Ward Mayor's denial of the NHI card based solely on his lack of residence status was illegal.

2. Reasoning on Lack of Negligence (State Compensation Act):

Despite finding the denial illegal, the Court denied the damages claim by finding no negligence on the part of the officials involved.

- Standard for Negligence in Legal Interpretation: The Court applied the established principle from state compensation law: If the interpretation of a law is genuinely disputed, with different viewpoints each having reasonable grounds, and administrative practice is divided, a public official generally does not act negligently by adopting one interpretation based on reasonable grounds (like official guidance), even if that interpretation is later deemed incorrect by the courts.

- Application to the Facts:

- The Ward Mayor's denial explicitly followed the MHLW administrative notices (本件各通知).

- These notices, requiring legal residence status for NHI coverage, were based on the general (and arguably reasonable) principle of limiting social security access to legal residents. The Court found these notices had "reasonable grounds" (sōtō no konkyo).

- Crucially, at the time of the denial (June 1998), the legal question of whether Article 5 covered undocumented residents was genuinely unsettled. There was no established legal consensus, lower court rulings were conflicting, and the only known relevant judgment at that time (a 1995 Tokyo District Court decision) actually supported the denial. There was no judicial precedent supporting the interpretation the Supreme Court itself now adopted.

- Conclusion on Negligence: Given this legal uncertainty, the existence of reasonably grounded administrative guidance supporting the denial, and the absence of contrary court precedent at the time, the Court concluded that neither the Yokohama City official making the decision nor the national MHLW officials who issued the guidance could be deemed negligent in performing their duties.

- Result: Without negligence, a key element for liability under the State Compensation Act was missing. Therefore, the claim for damages failed.

(Minority Opinion): Two justices dissented specifically on the legality finding (agreeing with the lack of negligence). They argued that "address" under Article 5 must imply legal residence status. They believed the majority's "high probability" test improperly burdened municipal officials with predicting immigration outcomes (a matter of broad federal discretion) and risked adverse selection.

Significance and Analysis

The 2004 Supreme Court decision is a landmark case with complex and somewhat paradoxical outcomes regarding social security access for undocumented residents in Japan.

- Potential Eligibility for Undocumented Residents: The most striking aspect is the Court's finding that NHI Act Article 5 does not automatically exclude all undocumented foreigners. It established, for the first time at the Supreme Court level, a specific (though demanding) set of criteria under which long-term, settled undocumented residents actively seeking to regularize their status could potentially qualify for NHI based on having a sufficiently stable "address." This acknowledged the reality of long-term undocumented residence and opened a theoretical legal door to coverage.

- Practical Difficulties and the "High Probability" Test: While opening a door, the test itself – requiring registration, a pending application for special residence, and a context-dependent assessment of the "high probability" of future stable residence – created significant practical challenges. It placed a difficult predictive burden on local welfare officials, requiring them to essentially second-guess immigration authorities' discretionary decisions. This inherent uncertainty was highlighted by the dissenting justices.

- The Subsequent Regulatory Override: The practical impact of the Court's interpretation of Article 5 was short-lived. Foreseeing the difficulties or perhaps disagreeing with the policy implication, the MHLW acted quickly. Citing the Court's own obiter dictum acknowledging the permissibility of explicitly excluding undocumented residents via regulation, the ministry amended the NHI Enforcement Regulations in June 2004 (effective July 2004) to add "those without residence status under the Immigration Control Act" to the list of statutory exclusions under Article 6. This regulatory amendment effectively closed the door that the Supreme Court's statutory interpretation had opened, making the Court's specific test for Article 5 largely moot for future cases regarding undocumented residents.

- Negligence Standard in State Compensation: The case provides a clear illustration of the high bar for establishing government negligence required for state compensation claims when dealing with actions based on disputed legal interpretations. Even if an administrative action is later found illegal due to an incorrect interpretation of law, officials may be shielded from liability if their interpretation was reasonable given the legal uncertainty and official guidance available at the time of the action. This protects officials from being penalized for reasonably relying on existing interpretations before the courts provide definitive clarification.

- Interplay of Laws: The case highlights the complex interaction between social security law (NHI Act), immigration law (determining legal status and residence permission), and constitutional principles (equality, minimum standards). It demonstrates that while social security law might be interpreted somewhat independently, immigration status remains a critical, often decisive, factor in determining eligibility for benefits for non-nationals.

Conclusion

The 2004 Supreme Court ruling presented a nuanced outcome. It found that, based purely on the text of Japan's National Health Insurance Act at the time, a long-term undocumented resident actively seeking to regularize their status could potentially meet the "address" requirement for eligibility under specific factual circumstances demonstrating stability and likely future residence. Accordingly, the denial of an NHI card to the appellant in this specific case was deemed illegal. However, the Court simultaneously denied the appellant's claim for damages, finding that the officials who made the decision and issued the guiding notices were not negligent, given the significant legal uncertainty surrounding the issue at the time and the existence of reasonably grounded administrative guidance supporting their interpretation. While the ruling briefly opened a possibility for NHI coverage for some undocumented residents based on statutory interpretation, this window was quickly closed by subsequent regulatory changes explicitly excluding them. The case remains significant for its analysis of the term "address" in the context of non-nationals, its illustration of the standard for government negligence, and its demonstration of the complex legal and policy considerations surrounding social security access for vulnerable non-citizen populations.