Reservoir Safety vs. Property Rights: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Uncompensated Restrictions

Date of Judgment: June 26, 1963

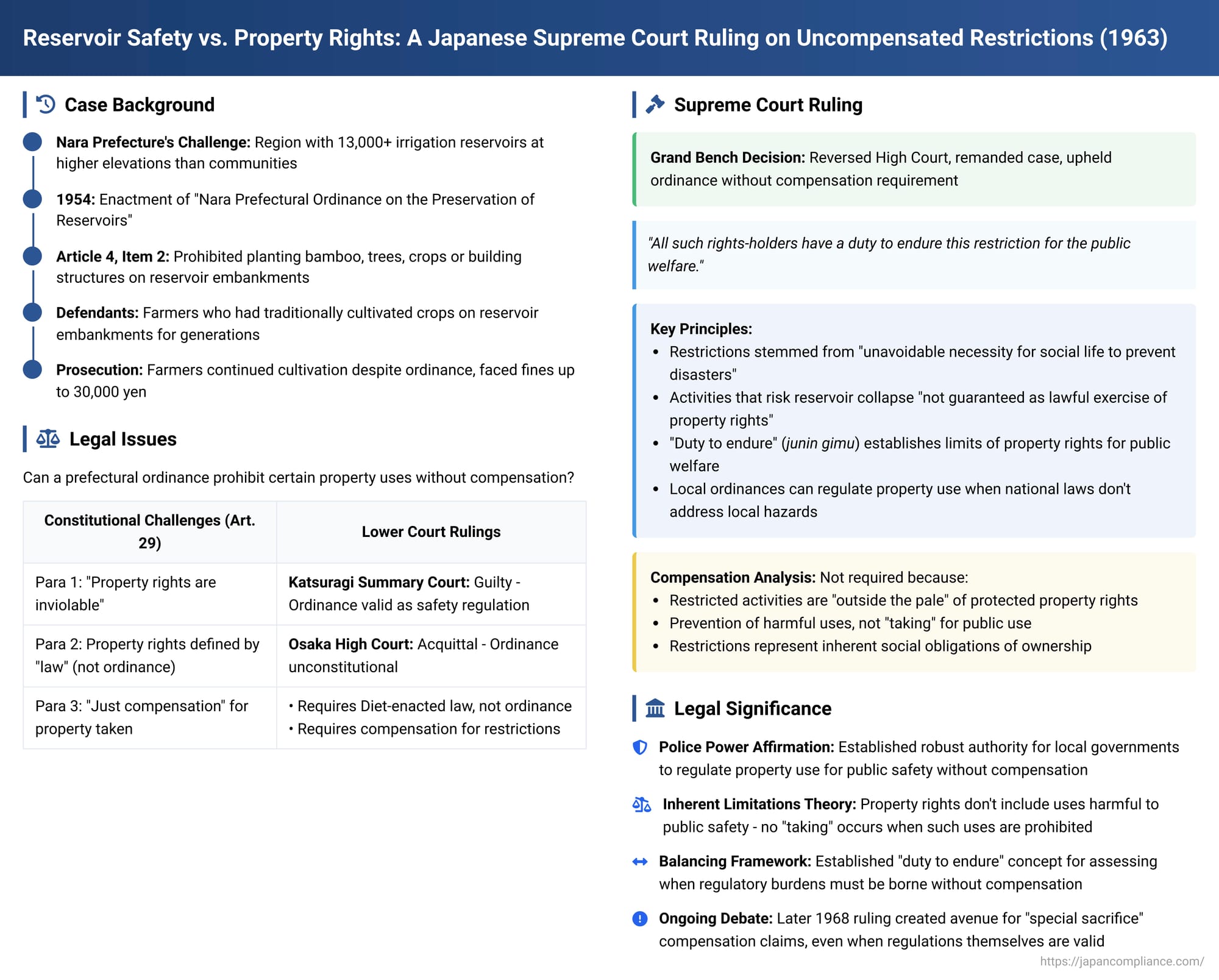

Case: Case Concerning a Violation of the Ordinance on the Preservation of Reservoirs

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction: Balancing Public Safety and Private Property

The exercise of private property rights, while a cornerstone of modern legal systems, is rarely absolute. A recurring tension exists between the rights of individuals to use their property as they see fit and the inherent power of the state to regulate such use for the broader public welfare, particularly to ensure public safety and prevent harm. This tension often crystallizes in situations where regulations impose significant restrictions on property use without offering monetary compensation. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court case, decided on June 26, 1963, grappled with these issues in the context of an ordinance aimed at preventing disasters from the collapse of agricultural reservoirs.

Nara Prefecture, a region historically reliant on a vast network of over 13,000 man-made irrigation reservoirs (tameike), faced a significant public safety challenge. These reservoirs, essential for rice cultivation, often sit at higher elevations than the surrounding communities. If their embankments (teitō) are weakened—for instance, by the roots of plants or trees—they can breach or collapse, unleashing devastating floods upon downstream lives and property. The 1963 Supreme Court case examined the constitutionality of a Nara Prefectural ordinance that prohibited certain activities on these embankments to prevent such disasters, notably without providing compensation to affected property rights holders.

The Nara Reservoir Ordinance: A Measure for Public Safety

In response to a history of damaging reservoir failures, Nara Prefecture enacted the "Nara Prefectural Ordinance on the Preservation of Reservoirs" in 1954. The stated purpose of this Ordinance (Article 1) was "to prevent disasters due to the damage, collapse, etc., of reservoirs by stipulating necessary matters concerning the management of reservoirs."

A key provision, Article 4, Item 2, prohibited anyone from "planting bamboo, trees, or agricultural crops, or establishing buildings or other structures (excluding those necessary for reservoir preservation) on reservoir embankments." Violations of this prohibition were punishable by fines of up to 30,000 yen under Article 9 of the Ordinance.

The defendants in the case were farmers. For generations, predating the Ordinance, their families had cultivated bamboo, fruit trees, tea plants, and other crops on the embankment of a specific reservoir. This reservoir was considered to be under the collective ownership (sōyū) of the local farming community, which included the defendants. Despite being aware that the new Ordinance applied to their reservoir and forbade their traditional cultivation practices, the defendants continued these activities. As a result, they were prosecuted for violating the Ordinance.

The Legal Challenge: Property Rights and Lack of Compensation

The farmers mounted a constitutional defense. They argued that the Ordinance, by effectively stripping them of their long-standing rights to use the embankment for cultivation without any form of compensation, was unconstitutional. Specifically, they contended that it violated:

- Article 29, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution, which guarantees that "the right to own or to hold property is inviolable."

- Article 29, Paragraph 2, which states that "Property rights shall be defined by law, in conformity with the public welfare," arguing that a mere prefectural ordinance was not a "law" (法律 - hōritsu, typically meaning a Diet-enacted statute) in this constitutional sense.

- Article 29, Paragraph 3, which requires "just compensation" when private property is taken for public use.

The legal journey of the case through the lower courts was marked by sharply contrasting conclusions:

- The first instance court (Katsuragi Summary Court) found the defendants guilty and imposed fines. It reasoned that cultivating the reservoir embankment in a manner that could weaken it constituted an abuse of property rights. Therefore, the Ordinance prohibiting such inherently risky activities was a valid exercise of regulatory power and constitutional.

- The appellate court (Osaka High Court) took the opposite view. It overturned the convictions and acquitted the defendants. The High Court held that: (1) The regulation of private property rights, as envisioned by Article 29, Paragraph 2, must be undertaken by "law" enacted by the National Diet, and a local ordinance did not meet this requirement. (2) Any restriction on private property rights, even if based on law, necessitates compensation for the loss incurred, as per Article 29, Paragraph 3. Since the Nara Ordinance provided no such compensation, it was unconstitutional on this ground as well.

The Public Prosecutor, representing the state, appealed the Osaka High Court's acquittal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Ordinance Without Compensation

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court reversed the Osaka High Court's decision and remanded the case, effectively paving the way for the defendants' convictions to be reinstated. The Supreme Court's reasoning established significant principles regarding the state's power to regulate property use for public safety.

Nature and Purpose of the Restriction:

The Court acknowledged that Article 4, Item 2 of the Ordinance, by prohibiting cultivation and construction on reservoir embankments, imposed a "near-total ban on the use" for those holding property rights to such use, thereby "significantly restricting" these rights.

However, it emphasized that the prohibited activities were those which legislators, based on scientific evidence, had identified as potential causes of reservoir damage or collapse. The overarching purpose of the Ordinance, clearly stated in its first article, was the prevention of disasters. This prohibition, the Court noted, applied universally to all persons, irrespective of whether they held pre-existing property rights to use the embankments.

The "Duty to Endure" (Junin Gimu):

A central pillar of the Supreme Court's reasoning was the concept of a "duty to endure" (junin gimu). The Court stated that while property rights holders were indeed substantially restricted in their use of the embankments, this restriction stemmed from an "unavoidable necessity for social life to prevent disasters." Therefore, the Court held:

"all such rights-holders have a duty to endure this restriction for the public welfare."

Acts "Outside the Pale" of Constitutional Protection:

The Court went further, asserting that using reservoir embankments in a manner that could lead to their damage or collapse is not a form of property use that enjoys constitutional protection in the first place. Such activities, it reasoned, are "not guaranteed as a lawful exercise of property rights by either the Constitution or the Civil Code." They are, in effect, "outside the pale" (rachigai) of legitimately protected property rights.

Consequently, prohibiting and penalizing these inherently dangerous activities through a local ordinance did not conflict with or deviate from the Constitution or higher laws. The Court also noted that no existing national laws specifically covered such prohibitions for reservoirs, making regulation by local ordinance appropriate for addressing particular local conditions like those in Nara Prefecture.

No Compensation Required under Article 29, Paragraph 3:

Based on this foundation, the Supreme Court addressed the compensation issue. It concluded that because the Ordinance was designed to "prevent disasters and maintain public welfare," and the restrictions it imposed, though severe, were an "unavoidable necessity for social life" and a "duty that property rights holders must naturally endure," compensation under Article 29, Paragraph 3 was not required. The restriction was not seen as a "taking" of a protected property right for public use in the traditional sense that would trigger a compensation requirement, but rather as a regulation preventing a harmful use of property that fell within the inherent power of the state to protect public safety.

The judgment was accompanied by several supplementary and minority opinions, indicating a diversity of views among the justices on the nuanced legal questions involved.

Unpacking the Reasoning: Inherent Limitations and Public Welfare

The 1963 Nara Reservoir Ordinance case is a leading example of the legal principle that property rights are not absolute but are subject to inherent limitations designed to protect the public welfare. This concept, often referred to as the state's "police power" in other legal systems, allows the government to regulate the use of private property to prevent harm to the community, even if such regulations diminish the property's economic value or restrict its owner's freedom of use.

The Supreme Court's decision emphasized the "social responsibility" aspect of property ownership. The right to use one's property does not extend to activities that pose a significant risk of disaster to others. In such cases, the restriction is viewed not as an expropriation of a right, but as a definition of the boundaries of lawful, socially responsible property use.

The precise legal pathway through which the majority opinion reached its conclusion was somewhat complex, reflecting differing underlying views among the justices at the time, particularly concerning the interpretation of Article 29, Paragraph 2 (property rights to be defined by "law"). Some justices, through supplementary opinions, explored whether an ordinance could directly define the "content" of property rights or merely regulate their "exercise." However, the modern understanding, and arguably the functional outcome of this judgment, is that ordinances enacted by local public entities can indeed serve as a legitimate basis for restricting property rights when such restrictions are necessary for the public welfare, such as preventing imminent public harm. The Court recognized that local conditions, like the prevalence of reservoirs in Nara, might necessitate tailored local regulations.

The Compensation Question Revisited

The Court's finding that no compensation was required was a direct consequence of its characterization of the Ordinance. If the prohibited activities were already "outside the pale" of protected property rights, then prohibiting them did not constitute a "taking" of anything the owners were constitutionally entitled to, thus negating the need for compensation under Article 29, Paragraph 3.

This aspect of the ruling, however, drew criticism. Some legal scholars argued that the decision was harsh, particularly given the defendants' families' long-standing, hitherto accepted practice of cultivating the embankments. This prolonged use, they contended, had created a de facto right or legitimate expectation, the deprivation of which, even for valid safety reasons, should have warranted some form of compensation, especially considering the severity of the prohibition (a near-total ban on their established use). One supplementary opinion in the case also expressed unease about the lack of compensation for the necessary removal or abandonment of existing crops and trees planted before the Ordinance came into effect.

It is important to note that this case was a criminal proceeding where the defendants were challenging the validity of the Ordinance as a defense against penalties. It was not a direct civil suit demanding compensation. A significant later development in Japanese constitutional law occurred with a Supreme Court decision on November 27, 1968, which recognized that individuals could directly sue for compensation under Article 29, Paragraph 3 if a lawful property regulation caused them a special sacrifice but the regulating law or ordinance itself lacked a compensation provision. This means that if a similar case arose today, while the ordinance imposing the safety restrictions might still be upheld as constitutional, affected property owners might have a separate avenue to seek compensation if they could demonstrate a "special sacrifice" beyond the general duty to endure reasonable public safety regulations.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1963 Nara Reservoir Ordinance case is a landmark decision in Japanese constitutional law, powerfully affirming the authority of the state, including local governments through their ordinances, to impose significant, uncompensated restrictions on the use of private property when deemed essential for public safety and disaster prevention. The concept of the property owner's "duty to endure" such limitations in the interest of the collective good lies at the heart of this judgment.

The ruling delineates a crucial boundary: restrictions aimed at preventing uses of property that are inherently harmful or dangerous to the public may not qualify as "takings" requiring compensation, but rather as an enforcement of the inherent social obligations that accompany property ownership. While the specific facts presented a difficult balance between long-standing traditional use and urgent public safety needs, the case remains a foundational precedent for understanding the scope of regulatory power and the limits of constitutional claims for compensation when property rights intersect with the paramount need to protect the community from harm.