Reserved Portions and Gifts to Heirs: Defining the "Value" for Abatement in Japan

Decision Date: February 26, 1998

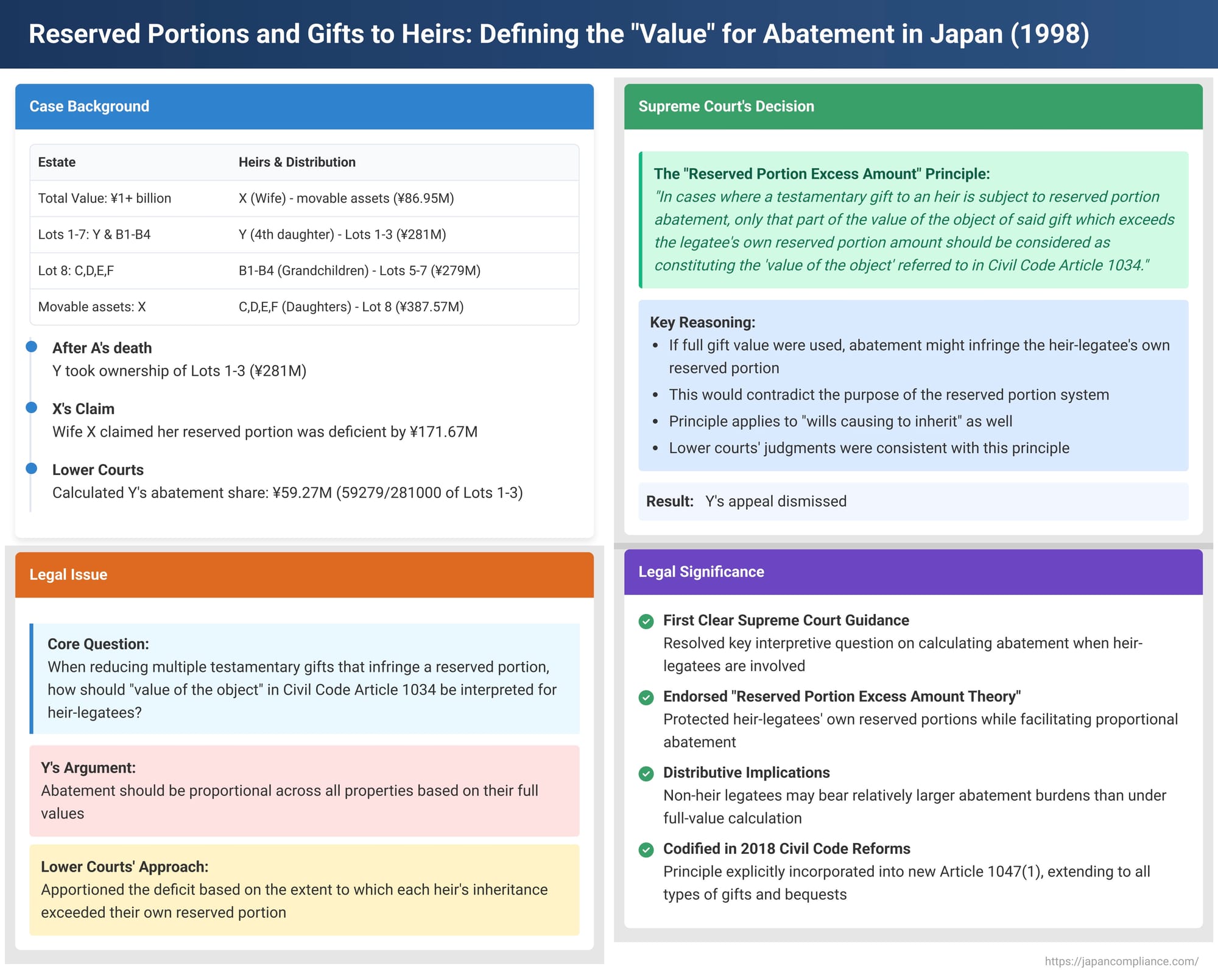

On February 26, 1998, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant ruling that clarified a crucial aspect of reserved portion (iryūbun) law under the then-existing Civil Code. The case, Heisei 9 (O) No. 802, centered on how to determine the "value of the object" of a testamentary gift when calculating abatement shares, particularly when the recipient of the gift was also an heir entitled to their own reserved portion. This decision had important implications for fairly distributing the burden of reserved portion claims among multiple beneficiaries.

I. The Complex Family Inheritance

The case involved the estate of A, who had passed away leaving a detailed will distributing his substantial assets, valued at over ¥1 billion, among his numerous heirs. The heirs included:

- X: A's wife (the plaintiff).

- Y: A's fourth daughter (the defendant/appellant).

- B1, B2, B3, B4: Children of A's predeceased eldest son, B, inheriting by representation.

- C, D, E, F: A's other daughters.

In total, there were ten heirs to A's estate.

A's will stipulated a specific distribution of his properties:

- Real Estate Lots 1-7: To be inherited 1/2 by Y and 1/2 collectively by B1-B4.

- Real Estate Lot 8: Valued at approximately ¥387.57 million, to be inherited in equal shares by daughters C, D, E, and F.

- Movable Assets (including bank deposits): Valued at approximately ¥86.95 million, to be inherited by X (A's wife).

Following A's death, Y and the B1-B4 group divided the Lots 1-7 properties amongst themselves. Y ultimately took ownership of Lots 1-3, valued at approximately ¥281 million, and completed the necessary ownership transfer registrations. The B1-B4 group received Lots 5-7, valued at ¥279 million.

X, A's wife, found that the assets bequeathed to her under the will were insufficient to satisfy her legally reserved portion of the estate. She subsequently exercised her reserved portion claim against Y and the B1-B4 group, demanding confirmation of her co-ownership share in the real estate they had received and the corresponding transfer registration. During the first instance court proceedings, X reached a settlement with the B1-B4 group. The dispute continued with Y.

II. Lower Court Rulings on Abatement

The first instance court calculated that X's reserved portion was deficient by ¥171,674,000. To satisfy this, the court determined the amount Y should contribute. It did this by apportioning X's deficit among the other co-heirs (Y, C, D, E, F, and the B1-B4 group) based on the extent to which the value of the assets each of them received exceeded their own individual reserved portion amounts. Y's share of this abatement was calculated to be ¥59,279,000. Consequently, the court confirmed X's co-ownership in Lots 1-3 (held by Y) to the extent of a 59279/281000 share and ordered Y to complete the share transfer registration.

The appellate court upheld this decision, dismissing Y's appeal. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that when multiple properties are subject to abatement, the abatement should be carried out proportionally across all such properties according to their respective values, implying a different method of calculation than that used by the lower courts.

III. The Supreme Court's Clarification: The "Reserved Portion Excess Amount" Principle

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, affirming the lower courts' approach. The central issue addressed by the Supreme Court was the interpretation of former Civil Code Article 1034, which governed how abatement is apportioned when multiple testamentary gifts infringe upon a reserved portion. The article stated that such gifts are to be abated "in proportion to the value of their objects" (その目的の価額の割合に応じて減殺する). The question was: when the recipient of a gift (a legatee) is also an heir entitled to their own reserved portion, what constitutes this "value of the object"?

The Supreme Court ruled:

"In cases where a testamentary gift to an heir is subject to reserved portion abatement, only that part of the value of the object of said gift which exceeds the legatee's own reserved portion amount should be considered as constituting the 'value of the object' referred to in Civil Code Article 1034."

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

If the entire value of the gift to an heir-legatee were to be considered the "value of the object" for apportionment purposes, it could lead to a situation where the abatement itself infringes upon that heir-legatee's own reserved portion. The Court found that "such a result would contradict the purpose of the reserved portion system," which aims to secure a minimum inheritance share for all entitled heirs, including the heir-legatee.

The Supreme Court also explicitly stated that this principle applies equally to "wills causing to inherit" (相続させる旨の遺言), like the one in this case, where specific assets are designated to be inherited by specific heirs. These are treated similarly to testamentary gifts for reserved portion purposes.

Since the lower courts' judgments were consistent with this "reserved portion excess amount" principle, their decisions were upheld.

IV. Analysis and Lasting Impact of the Ruling

This February 26, 1998, Supreme Court decision was a landmark in Japanese inheritance law, particularly concerning the mechanics of reserved portion claims.

A. Resolving a Key Interpretive Question

The ruling provided the first clear Supreme Court guidance on how to calculate the abatement base when an heir-legatee is involved and multiple gifts are abated proportionally. Under the former Civil Code Article 1034, if there were several testamentary gifts that, together, infringed upon an heir's reserved portion, these gifts were to be reduced proportionally according to their "value." The ambiguity lay in defining this "value" when the recipient was also an heir with their own reserved portion rights.

B. Adoption of the "Reserved Portion Excess Amount Theory"

The Supreme Court effectively endorsed what legal scholars termed the "reserved portion excess amount theory" (遺留分超過額説). This view, which was the majority opinion among academics even before this ruling, posits that an heir-legatee is inherently entitled to their own reserved portion. Therefore, only the value of the gift or bequest that exceeds this personal reserved portion amount can be considered truly "gifted" in a way that is freely disposable by the testator and thus fully available for abatement by other reserved portion claimants.

The primary rationale supporting this theory, and adopted by the Court, is the avoidance of circularity and further infringement. If the full value of a gift to an heir-legatee were abated, and this abatement dipped into their own reserved portion, that heir-legatee would then have to make their own reserved portion claim against other beneficiaries, leading to a cascade of claims and instability.

C. Alternative Approaches Considered

The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that alternative theories had been proposed by scholars. For instance:

- One could use the full value of all gifts for the initial apportionment calculation but then cap the actual abatement from an heir-legatee at the amount exceeding their own reserved portion. This differs subtly in how the proportions are initially set.

- Another view suggested using the value of the gift exceeding the heir-legatee's statutory inheritance share (法定相続分) as the basis, with adjustments if this was less than their reserved portion.

The Supreme Court’s choice of the "reserved portion excess amount theory" directly addressed the value forming the basis of the apportionment itself.

D. Implications and Nuances of the Chosen Theory

While the "reserved portion excess amount theory" simplifies calculations and protects the heir-legatee's own reserved portion from being diminished by another's claim, it has certain distributive consequences. As noted in legal commentary, compared to an apportionment based on the full value of all gifts, this method can result in non-heir legatees, or heir-legatees with smaller reserved portions, bearing a relatively larger share of the abatement burden. The Supreme Court's judgment focused on preventing the infringement of the recipient-heir's reserved portion but did not delve into a deeper comparative justification of why this specific apportionment method was superior to others in all respects of fairness among different classes of beneficiaries.

The ruling's scope is understood to apply generally whenever an heir is a recipient of a testamentary gift subject to abatement, irrespective of whether their own reserved portion would actually be infringed in a specific instance if a full-value apportionment were used.

E. Codification in the 2018 Civil Code Reforms

The principles laid down in this 1998 Supreme Court decision have proven to be of enduring importance. The PDF commentary highlights that the 2018 reforms to Japan's Civil Code (which took effect in stages, largely from 2019) explicitly incorporated the "reserved portion excess amount theory" into the new Article 1047, paragraph 1. This article now clearly states that when a beneficiary subject to a reserved portion claim is also a reserved portion holder, they bear the obligation to satisfy the claim only to the extent that the value of the benefit they received exceeds their own reserved portion amount. This codification also extended the principle to cover specific property bequests via "causing to inherit" wills and designations of inheritance shares. The primary rationale cited for this codification in the new law mirrors that of the 1998 Supreme Court decision: to prevent circularity of claims and the infringement of the beneficiary-heir's own reserved portion.

F. Ongoing Considerations

Even with the codification, the PDF commentary suggests that the inherent consequence of this theory—that the existence and size of an heir-legatee's own reserved portion always influences the abatement ratios among multiple beneficiaries—might continue to be a point of discussion regarding its broader equity implications. The theory logically flows from the premise that a gift to a reserved portion holder is only truly a "disposable" gift to the extent it surpasses their protected share.

V. Conclusion: Ensuring Stability in Reserved Portion Claims

The Supreme Court's February 26, 1998, judgment provided crucial clarity on a complex aspect of reserved portion abatement under the former Civil Code. By establishing that only the value of a gift to an heir exceeding their own reserved portion forms the basis for proportional abatement, the Court aimed to protect the integrity of each heir's protected share and prevent a domino effect of claims. This judicially crafted solution not only resolved a contentious legal issue at the time but also laid the groundwork for its formal adoption into Japan's current Civil Code, thereby contributing to greater stability and predictability in the resolution of reserved portion disputes involving multiple heirs and beneficiaries.