Res Judicata, Successors in Interest, and the Protection of Bona Fide Third Parties: Navigating Competing Claims After a Prior Judgment

Judgment Date: June 21, 1973 (First Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan)

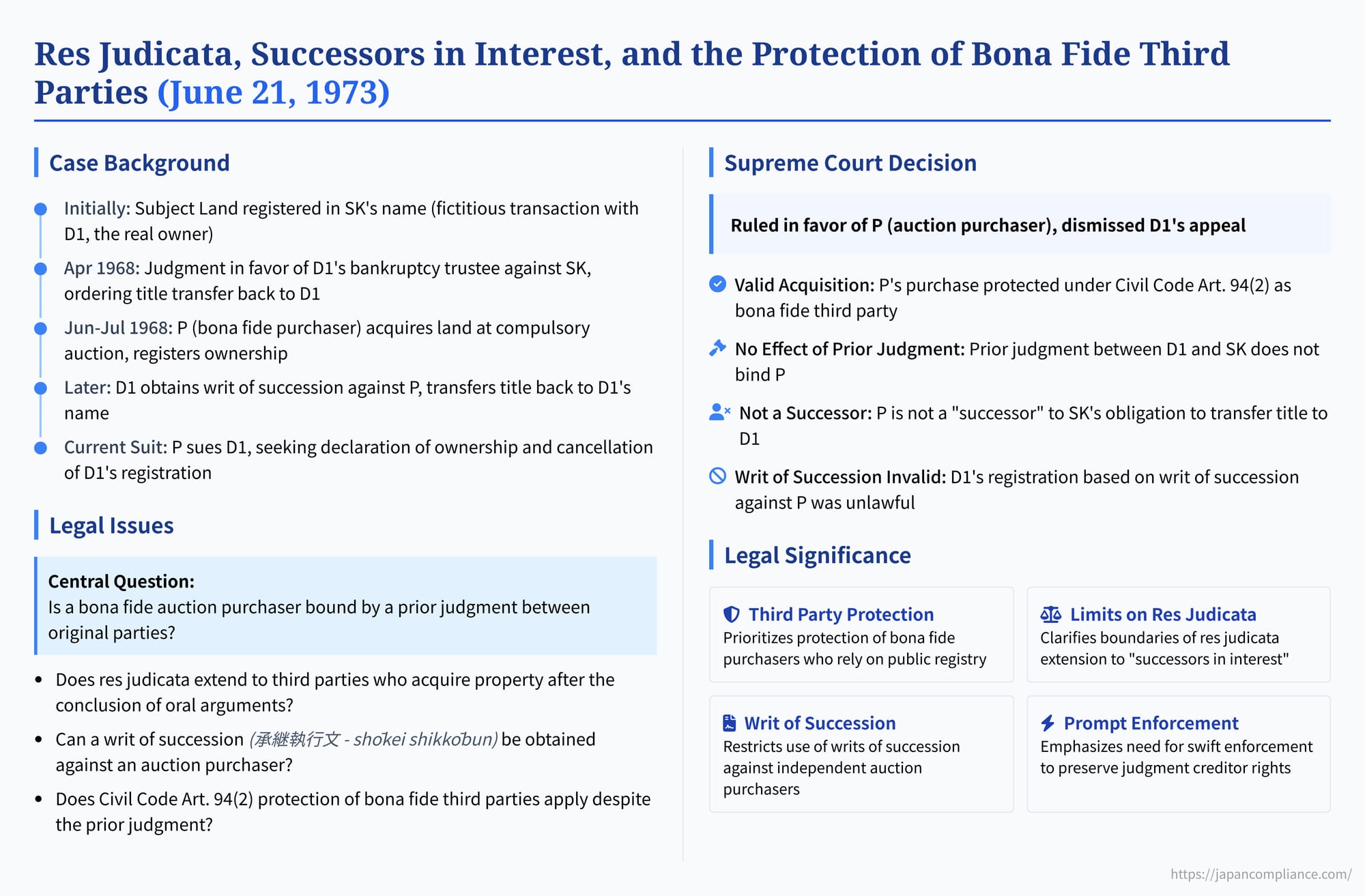

This 1973 Japanese Supreme Court decision delves into a complex interplay of property law, res judicata (既判力 - kihanryoku), and the rights of third parties who acquire property after the conclusion of oral arguments in a prior lawsuit but before that judgment is enforced. The case specifically addresses whether a bona fide purchaser at a compulsory auction can be defeated by a party who, based on a prior judgment against the original debtor, later obtains a writ of succession (承継執行文 - shōkei shikkōbun) against that purchaser and registers ownership. The Court affirmed the bona fide purchaser's rights, holding that the prior judgment did not bind them in this scenario and the subsequent enforcement against them was unlawful.

Case Background: A Fictitious Registration, a Lawsuit to Recover Title, and a Bona Fide Auction Purchaser

The factual background, as established by the lower court, is as follows:

- The Initial Fictitious Registration: The Subject Land was originally registered in the name of Sachiko Kobayashi (a non-party, hereinafter "SK"). However, this registration was a result of a fictitious transaction (通謀虚偽表示 - tsūbō kyogi hyōji) between Ryohei Hirokawa (appellant, one of the defendants in the current suit, hereinafter "D1") and SK. In reality, the Subject Land belonged to D1.

- The Prior Lawsuit (Zen-so - D1's Bankruptcy Trustee vs. SK):

- D1's bankruptcy trustee sued SK, asserting that the registration in SK's name was void due to the fictitious transaction and seeking an order for SK to transfer the ownership registration of the Subject Land back to D1 for the purpose of restoring true title.

- This lawsuit (Nagoya District Court, Okazaki Branch, 1967 (Wa) No. 2206) concluded oral arguments on April 17, 1968. On April 26, 1968, a judgment was rendered in favor of D1's bankruptcy trustee, ordering SK to make the transfer. This judgment became final and binding around that time.

- P's Acquisition of the Land at Auction:

- Takuji Gomi (appellee, plaintiff in the current suit, hereinafter "P") was unaware of these circumstances (i.e., P was a bona fide third party).

- In a compulsory auction proceeding against SK (as the execution debtor), P successfully bid for the Subject Land on June 27, 1968 (which was after the conclusion of oral arguments in the Prior Lawsuit between D1's trustee and SK).

- P completed the ownership acquisition registration on July 22, 1968.

- D1's Subsequent Enforcement Action Against P:

- D1 (or D1's trustee, acting on D1's behalf) then obtained a writ of succession (承継執行文 - shōkei shikkōbun) for the final judgment from the Prior Suit, naming P as SK's successor in interest concerning the obligation to transfer title.

- Based on this writ of succession, D1 completed an ownership transfer registration for the Subject Land back into D1's name, effectively overriding P's auction-based registration.

- The Current Lawsuit (Hon-so - P vs. D1 and Others): P filed the current lawsuit seeking, among other things, a declaration that P owned the Subject Land and an order for D1 (and other related parties) to cancel the ownership transfer registration that D1 had made based on the writ of succession. The lower courts ruled in favor of P. D1 appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment and Reasoning

The Supreme Court dismissed D1's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of P.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Effect of Fictitious Transaction Against a Bona Fide Third Party (Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2):

- D1 could not assert the invalidity of the ownership registration in SK's name (which was based on a fictitious transaction between D1 and SK) against P, because P was a bona fide third party who was unaware of the fictitious nature of SK's title when P purchased the land at the compulsory auction.

- Therefore, P validly acquired ownership of the Subject Land through the auction and subsequent registration.

- Prior Judgment's Res Judicata Does Not Affect P's Title:

- The existence of the prior final judgment between D1 (represented by the bankruptcy trustee) and SK, which ordered SK to transfer title to D1, does not affect P's acquisition of ownership.

- P was not a party to that Prior Lawsuit, and P acquired title from SK (via the compulsory auction which treated SK as the owner based on the public registration) after the oral arguments in the Prior Lawsuit had concluded.

- P is Not a "Successor" to SK's Obligation to D1:

- Crucially, P did not "succeed" (承継 - shōkei) to SK's obligation to transfer the Subject Land's ownership registration to D1. P's acquisition was an independent one through a compulsory auction based on SK's apparent ownership.

- Since P was not SK's successor regarding that specific registration transfer obligation established in the Prior Suit, it was impermissible for D1 to obtain a writ of succession against P based on the judgment against SK and to enforce that judgment against P.

- Illegality of D1's Subsequent Registration:

- The appellate court found that D1 had, in fact, obtained such a writ of succession against P and, based on it, had registered the ownership of the Subject Land back to D1.

- This act by D1 was unlawful, and the resulting registration in D1's name was void, as P had already validly acquired ownership as a bona fide third party.

The Supreme Court concluded that the appellate court's judgment, which was to the same effect, was correct and that D1's appeal was without merit.

Significance and Commentary (Drawing from the Provided PDF - ms82.pdf)

This 1973 Supreme Court decision is pivotal in clarifying the rights of a bona fide third party who acquires property from a person whose registered title is based on a fictitious transaction, especially when this acquisition occurs after the conclusion of oral arguments in a lawsuit aimed at rectifying that fictitious registration but before that judgment is enforced against the third party.

Key aspects highlighted by the PDF commentary include:

- Protection of Bona Fide Third Parties (Civil Code Art. 94(2)): The bedrock of the decision is Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, which states that the invalidity of a fictitious manifestation of intent cannot be asserted against a bona fide third party. P, having acquired the land at a compulsory auction without knowledge of the fictitious nature of SK's registered title, qualified as such a protected third party. ([Source: The judgment itself])

- Res Judicata and "Successors After Conclusion of Oral Arguments":

- Generally, the res judicata of a final judgment extends to "successors in interest after the conclusion of oral arguments" (口頭弁論終結後の承継人 - kōtō benron shūketsu-go no shōkeinin) under Article 115, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Code of Civil Procedure. This means that if a defendant is ordered to transfer property, someone who acquires that specific obligation or the property from the defendant after the lawsuit's critical date is usually bound by the judgment.

- The "Formal" vs. "Substantive" Theories of Succession: The PDF commentary discusses the academic debate between the "formal theory" (形式説 - keishiki-setsu) and the "substantive theory" (実質説 - jisshitsu-setsu) regarding who qualifies as a "successor" bound by res judicata. ([Source 2])

- Formal Theory (Majority View): A person is a successor if they acquire the disputed right or object of litigation after the standard time. However, such a successor can still assert their own independent defenses (固有の抗弁 - koyū no kōben) against the judgment creditor. The res judicata only prevents them from re-disputing what was decided between the original parties as of the standard time.

- Substantive Theory: A person is only a successor bound by res judicata if they do not possess such an independent defense.

- This Supreme Court decision, while not explicitly adopting either theory for res judicata in this context, focuses on the enforcement aspect through the writ of succession.

- Writ of Succession (承継執行文 - Shōkei Shikkōbun) and Its Limits:

- A writ of succession (Civil Execution Act, Article 27, Paragraph 2) allows a judgment creditor to enforce a judgment against a person who succeeded to the judgment debtor's obligation after the judgment became enforceable.

- The Supreme Court held that P was not a successor to SK's obligation to transfer the land to D1. P acquired the land through a distinct legal process (compulsory auction) based on SK's (albeit fictitiously created) registered ownership. P's acquisition was not a voluntary succession to SK's specific duty arising from the D1-SK judgment.

- Therefore, the issuance of the writ of succession against P was improper, and the subsequent registration transfer to D1 based on it was unlawful and void. ([Source 1], [Source 3])

- The Nature of the Obligation in an Ownership Transfer Claim: The PDF commentary delves into a nuanced point: a claim for ownership transfer registration based on ownership is a real right claim (物権的請求権 - bukkenteki seikyūken). Such a claim arises anew against anyone who is currently infringing the owner's right by holding an adverse registration. ([Source 3])

- Thus, if Y (D1 in the case) had a true underlying ownership right that was superior to X's (P's) acquired right, Y's claim against X would be a new claim arising when X obtained registration, not merely a "succession" to Y's claim against A (SK).

- This distinction is important because if X is not a successor to A's specific obligation under the prior judgment, the res judicata of that judgment (which primarily concerns the Y-A relationship regarding the transfer obligation) does not directly determine Y's new claim against X. X can assert P's own bona fide purchaser status under Civil Code Article 94(2) as an independent defense.

- Practical Implication: Importance of Prompt Enforcement and Protection of Intervening Rights: This case underscores that a judgment, even if final, might not be enforceable against a third party who, in good faith and without notice, acquires rights in the disputed property after the critical date of the judgment but before any measures (like provisional registration or actual enforcement) are taken to secure the judgment creditor's rights against the property itself. The bona fide purchaser at an auction, relying on the public registry, is strongly protected.

In essence, the Supreme Court prioritized the protection of the bona fide third-party purchaser (P) who relied on the public land registry, over the claims of the original "true" owner (D1) who had been a party to creating the fictitious registration in the first place, even though D1 had obtained a judgment to rectify that title against the nominee owner (SK). The key was that P was not a successor to SK's specific obligation determined in the prior lawsuit and had acquired independent rights as a bona fide purchaser.